UCSD study may suggest autism’s cellular basis

A new study led by researchers at UCSD has found that boys with autism had two-thirds more cells in the area of their brain associated with social, cognitive and communication development.

Researchers at the UCSD Autism Center of Excellence found a 67 percent average excess of cells in the prefrontal cortex — cells that are made only around the second trimester of pregnancy — using brain tissue from seven deceased boys with autism.

The study represents the first time autism researchers have counted cortical cells.

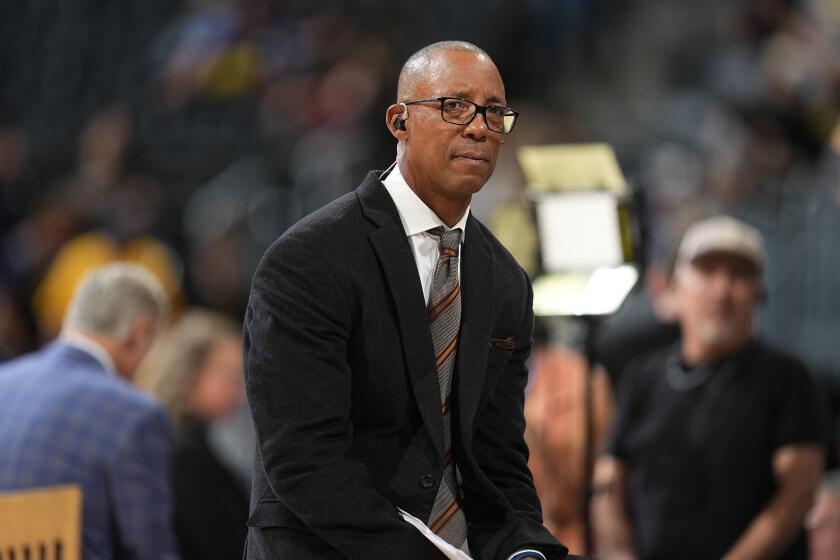

“What we found was very surprising,” said lead researcher and center director Dr. Eric Courchesne. “This changes the kind of research we should be thinking about doing.”

What its authors described as a “small, preliminary study” will be published Wednesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Courchesne said he believes the study demonstrates for the first time the underlying cellular basis for autism and that it occurs before birth. He said future research should focus on what may cause the overproduction of brain cells in the front third of the brain, such as genetics, environment and the mother’s health during pregnancy.

“This is very exciting,” he said. “I went into autism research for this very moment.”

Autism remains one of the most confounding of childhood disorders that challenges researchers and haunts parents because of the significant social, communication and behavioral disabilities it can cause. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 1 in 110 children in the United States has some autism spectrum disorder.

Courchesne said that while he and other researchers have taken head measurements and done MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) on children with autism to gauge brain size and development, this study breaks new ground.

The sample was necessarily small, he said, because postmortem brain tissue from children is scarce. Researchers used all of the available tissue in the United States at the time of the study.

The scientists used brain tissue of seven deceased boys, ages 2 to 16, and a control group of postmortem brain tissue from six typically developing boys. Using a computerized analysis developed by co-investigator Dr. Peter R. Mouton at the University of South Florida, researchers not only found excess cortical cells among the children with autism but also that their brains weighed more than the control group’s.

The study did not determine a cause.

Cortical neurons grow profusely between the 10th and 20th week of pregnancy with a naturally occurring overabundance. In typically developing children, excess cells are destroyed during the third trimester of pregnancy and soon after birth.

The overabundance of cells in the autistic children, Corchesne said, could mean that cell destruction either didn’t occur or was insufficient.

Researchers were surprised to find that the overabundance of neurons only increased brain size by 17 percent rather than the 30 percent that would have been expected.

“So it could be, the size and brain volume underestimate the problem,” said Corchesne, who believes the study dovetails with his earlier research.

A 2003 study of 48 children with autism found average head size at birth actually was smaller than in most healthy newborns. That changed for children with autism at about 2 months, when their heads and brains experienced bursts of growth so that by 14 months their average brain size was larger than that of most healthy children. Growth then slowed and by age 5, their brains resembled the size of typically developing children.

Courchesne’s research with MRIs on children with autism, presented at a conference this year, found the rapid overgrowth in the first three years created a haphazard tangle of connective fibers between areas of the brain. Normally, the fibers grow more slowly over time so appropriate connections are made for social, communication and language development.

Corchesne said the new cell-count study shows the process of brain overgrowth begins before birth.

“The problem just lies hidden until about a year old,” he said.

One autism researcher voiced skepticism about the findings, in part because of the small sample size and because they appear to conflict with a dozen MRI studies.

“I think we have to exercise a fair amount of caution in drawing conclusions at this point,” said Dr. David Amaral, research director at the UC Davis MIND Institute. “The findings fly in the face of quite a few imaging studies of living kids with autism.”

Amaral said that if substantially more cortical cells are produced before birth in children with autism, as the UCSD study indicates, then he believes previous studies should have shown larger — not smaller — brain size in newborns.

Even given the findings, Amaral said he believes brain overgrowth in the first four years only occurs in a minority of children with autism.

The UC Davis institute is conducting a longterm Autism Phenome Project that enrolls children at about 2 1/2 years of age and follows them with annual MRIs, medical and behavioral tests, and genetic analyses. About 270 children have undergone MRIs, he said.

“MRIs show about 10 percent with (brain) volume outside the range of typically developing kids,” he said.

Amaral said he believes research will find that autism, like cancer, is caused by factors ranging from genetics to environment.

“What it’s beginning to look like is autism is a catch-all phrase for a series of disorders and there probably will be a multitude of causes and treatment,” he said.

At the University of Washington Autism Center, researcher Dr. Natalia Kleinhans said she was excited by the findings.

“I think this is an incredibly important study,” said Kleinhans, whose research focuses on brain connectivity using functional imaging. “If it’s true and can be replicated it really provides us with strong evidence pinpointing the exact mechanisms involved.”

Kleinhans said she was stunned by the dramatic number of excess cortical cells that were found and that it may provide some answers to the question of why some children with autism have brains that “get too big too fast.”

Eventually, she said, she hopes continuing research on the prenatal and early childhood mechanisms with autism “can give families and parents scientific evidence of the causes of autism, to help them make better decisions for their children.”

University of North Carolina researcher Dr. Heather Cody Hazlett called the research “thought-provoking.”

An assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at University of North Carolina, Hazlett has published studies using MRIs to document brain overgrowth in young children with autism.

“This is a small study but very thought-provoking, in that these postmortem findings support what we see in our structural MRI studies where brain enlargement is present in toddlers with autism prior to the age of 2,” Hazlett said. “As the authors point out, it’s unclear whether their finding of excess neurons is limited to prefrontal brain or is more global, but that would be an interesting follow-up study.”

The UCSD study was funded in part by an award given to Courchesne from the National Institute of Health’s Autism Center of Excellence, and by a National Institute of Mental Health grant given to Mouton.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.