Monsters are more made than born.

No person is born evil. We believe in cycles of abuse and we believe that damaged people become dangerous.

This raises uncomfortable questions about guilt. Are the deeply traumatized genuinely responsible for their actions? Legally, more often than not, they are. Morally, things are murkier.

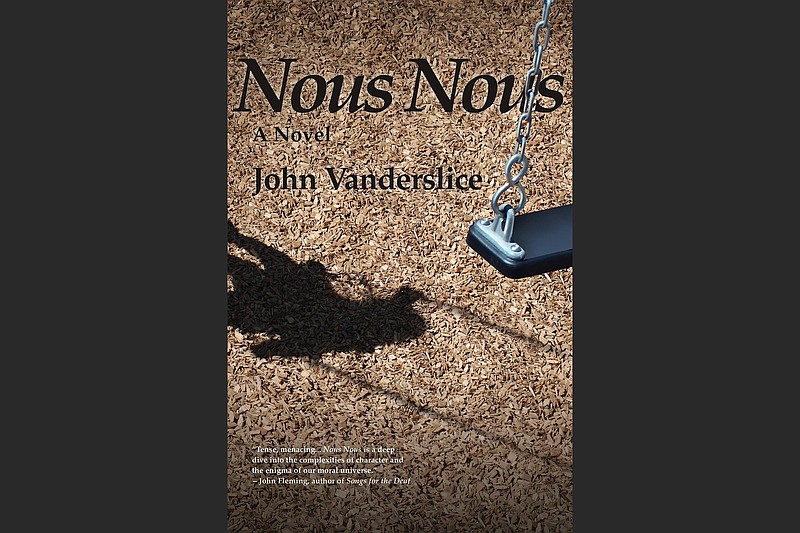

In John Vanderslice's new novel "Nous Nous," a bereaved father named Lawrence Baine kidnaps a middle-school girl out of a strange but bitterly logical notion that he is extracting justice from the universe for the loss of his own daughter. He has made a simple plan, renting a house on an Arkansas lake where he can carry it out. He has thought some things through. He is highly intentional. He has weighed it and decided upon revenge.

He thinks he can get away with it, but he's willing to live with whatever consequences he incurs from whatever gods may be.

Hours before he puts his plan in motion, Baine visits an Episcopal priest, recently divorced Elizabeth Riddle. She senses something off in him, manifested in the wine-red stain that covers half his face and his "reptilian" eyes. She cannot help but be a little afraid of him, and a little less than generous when he tells her he's thinking of killing someone.

She doesn't have time for his performative nonsense and is almost relieved when he bolts from her office while she goes to fetch a pamphlet for him to read, titled "Twenty Questions About the Episcopal Church."

But she goes out into the parking lot to look for him anyway.

Baine might acknowledge his own monstrosity, but he knows there are ways to make yourself look harmless. And one of the best ways is to walk a dog; the smaller and sillier the dog the better. He had procured a Pomeranian he names Cocteau specifically for this purpose: to provide him with a plausible reason to loiter outside the school and distract his quarry with an odd story he'll tell her about her mother being detained and wanting her to go with him for a little while.

There are at least a few ways to look at "Nous Nous," and the simplest reading is that it's a crime story, tense and suspenseful, that reminds me of network television's "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" anthology told from the perspective of multiple voices — the would-be killer; the victim, Elizabeth, and Angel, a student teacher who unknowingly witnesses the abduction.

Angel is a French student who has been trying with little success to interest the middle school students in the language. She has a feeling that the girl who becomes the victim is perhaps the only one she is reaching — though peer pressure has suppressed her vocal participation in the sessions.

One of Angel's lessons lends the book its title. She explains to the seventh-graders that French has "reciprocal" verbs "which tell us what we're doing with each other or to each other ... then you get a funny-sounding construction that I love: 'nous nous' .... such as, 'Nous nous retrouvons.' We are meeting each other."

I don't have a great grasp of idiomatic French, but "nous nous" might imply a larger "us," a community of man. More importantly, it phonetically sounds the same as the French word "nounou," which means "nanny," which would be a grimly bitter way to describe the kidnapper's relationship with his victim.

Take it one step further — "nous nous" equals "we we," which is phonetically identical to "oui oui," which means "yes yes," and which evokes the final chapter/paragraph of James Joyce's "Ulysses," Molly Bloom's famous life-affirming soliloquy.

That might seem a stretch, but it would be a mistake to doubt that Vanderslice considered all these factors when deciding on a title, for another way to look at "Nous Nous" is as a meditation on what it means to be trapped — whether we're being held hostage by a literal kidnapper or the conventions and mores of small-town Arkansas — and what it means to be released.

Vanderslice, a professor in the department of Film, Theatre, and Creative Writing at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway, has fashioned a deceptively literary thriller — a genuine page-turner — that sounds the depths and shallows of religious faith with generosity and compassion, even for his monster.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com