As the public edges toward impeachment, will the GOP follow?

It is an iconic moment in modern American history, the day in 1974 when the leaders of the Republican Party in Congress went to the White House to tell a Republican president he was through — that facing all but certain impeachment in a Democrat-controlled Congress, he couldn’t rely on support from his fellow Republicans. The day after that visit from Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania, and House Minority Leader John Rhodes of Arizona, Richard Nixon resigned.

As impeachment proceedings officially began in the House this week, speculation quickly turned to how they might end in the Senate. Articles of impeachment are drafted and voted on in the House, leading to a trial in the Senate. Unlike in 1974, Republicans now have a Senate majority. It would therefore require at least 20 votes from Donald Trump’s own party to reach the 67 necessary to remove him as president, assuming all Democrats and the two independents all vote to convict.

Could it happen? Thus far, Trump’s reputed stranglehold on the Republican base and his threats to support primary challenges to incumbents who oppose him have kept virtually the entire party in his corner. Rep. Justin Amash, the (very conservative) Michigan Republican, became the exception that proves the rule when he came out in favor of impeachment and was essentially thrown out of the party.

But it’s good to remember that in the early days of Watergate it had seemed unlikely that Republican minds would change, either. A year before his final trip to the Nixon White House, Goldwater had told Time magazine: “Watergate is the concern of every Republican I talk to. But both conservatives and liberals in the party are ready to stand behind the president.”

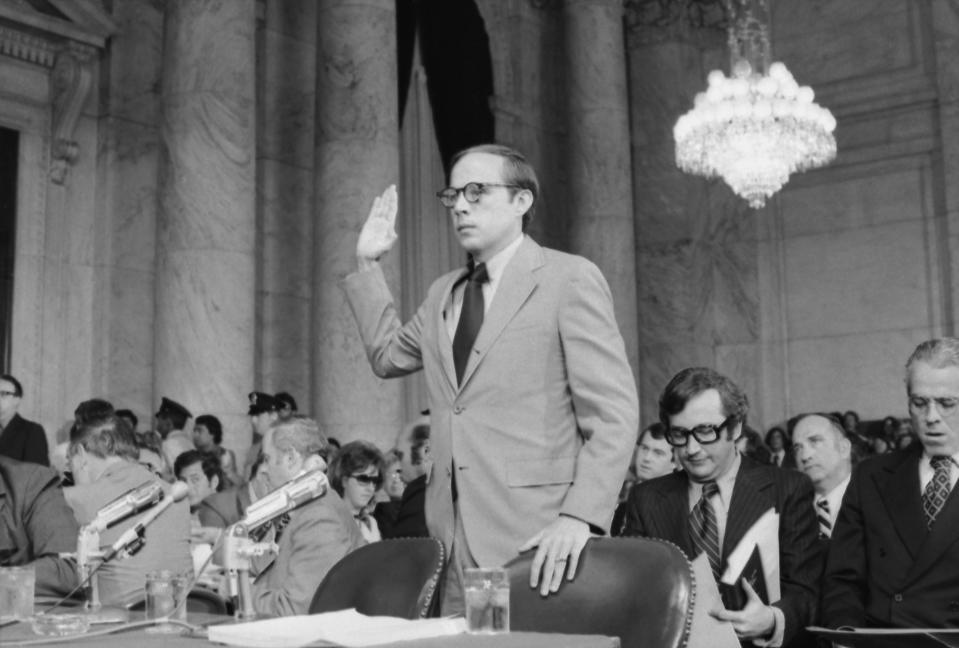

History similarly records as an act of courage and conscience the question posed in June 1973 in the Senate by Howard Baker Jr. of Tennessee: “What did the president know and when did he know it?” In fact, Baker was less interested in getting to the truth than in setting up a defense of Nixon. The question was directed at White House lawyer John Dean, aiming to get Dean to confirm that Nixon did not play a role in either the break-in at Democratic campaign headquarters or the subsequent cover-up. Instead, Dean testified to three dozen discussions with Nixon about that cover-up.

Dean’s testimony had the effect of bringing forth other witnesses with damning stories, and whether that will happen again during these hearings is another pivotal question. Are there more whistleblowers out there? Will future hearings be like the questioning of Dean or more like the stonewalling and theatrics of Corey Lewandowski?

There is a sociological model known as the cascade effect. A dinner party goes on and on, and finally someone stands up and says, usually with apology, that they must leave. Soon nearly everyone at the table is headed for the door. A lone agitator throws a rock through a window, and soon thousands are rioting. One well-known actress describes sexual abuse at the hands of a prominent Hollywood executive, and soon hundreds of women bring long-buried accusations to light. It can sometimes take a small group, even one person, to say what others are thinking and completely change the public equation.

But what does and doesn’t hit the mark and trigger the cascade isn’t always obvious. Victoria Bassetti, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU, and a Senate staffer during the Bill Clinton impeachment trial at which that president was not found guilty, has written of how Nixon and Baker tried to prevent the cascade phenomenon, only to have their orchestration backfire.

Baker was the ranking Republican on the Senate committee established to investigate Watergate, and in February 1973 he met secretly with Nixon to reveal that committee’s witness plan. Democrats wanted the hearings to begin with relatively minor players, Baker told Nixon, in the hope that their appearances would pave the way for testimony by more central figures. But Baker suggested, and then facilitated, the opposite approach, leading off with prominent Nixon loyalists such as White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman and top adviser John Ehrlichman in the expectation they would “deflate the whole thing,” according to Bassetti.

It didn’t work out that way. The appearance of two such prominent and controversial officials early on put a public face on the investigation and gave it momentum, setting off a cascade effect that reversed public opinion. Only 19 percent of Americans believed Nixon should be removed from office when the Senate Watergate hearings began in May 1973; by August 1974 it was nearly 60 percent.

For months polls have shown a majority of Americans against impeachment, but in the days since House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced her support, in one leading poll a narrow majority (49 percent to 46 percent) is now in favor. Republicans, however, are still firmly opposed (80 percent to 20 percent).

One factor in play at the moment that was not present in 1974 is the perceived power of the Republican base, whose loyalty to this president has remained fairly constant in spite of prior accusations of corrupt or unseemly behavior. Here history is little guide.

“To revisit that analogy of a dinner party,” Bassetti said in an interview with Yahoo News, “unlike a more usual one where when you leave you just go to your car, at this one you have to run the gauntlet through a mob that wants to beat you up before you get to your car. So you’re not going to see one person getting up from the dinner party. You’re going to see 30 people going to the restroom and then trying to sneak out the back.”

But there are some who predict that even some of the most conspicuous revelers at the president’s table might be eyeing their watches and the door. As Mike Murphy, former adviser to both Mitt Romney and John McCain, said on MSNBC Wednesday, “One Republican senator told me if it was a secret vote, 30 Republican senators would vote to impeach Trump.”

Tony Schwartz, who wrote “The Art of the Deal” but has become an outspoken critic of the president, said something similar on Twitter. “Oddsmakers say Trump Republicans ... won’t vote to impeach Trump,” he wrote. “I believe all bets are off. Most Republican senators privately hate him & his power over them. If they believe, by banding together, they can push him out, I think there is a very reasonable chance they will.”

To that, George Conway, a vocal Trump critic who is also the husband of Trump’s key adviser Kellyanne Conway, responded: “I agree with this. There may be Republican senators who won’t say a word until the moment they say “guilty” when the roll is called at the end of an impeachment trial.”

I agree with this. There may be Republican senators who won’t say a word until the moment they say “guilty” when the roll is called at the end of an impeachment trial. https://t.co/zQJ8xnEfeW

— George Conway (@gtconway3d) September 25, 2019

These analyses rely on the personal disdain many Republicans are suspected of harboring for Trump, and/or a sudden reawakening of conscience in the face of evidence that the president is corrupt or incompetent. That is how the famous visit to the White House by the trio of stonefaced Republicans was long portrayed: Goldwater, the party’s presidential nominee a decade earlier and the author of “The Conscience of a Conservative,” rising above partisanship, speaking truth to power, and telling his fellow Republicans “there are only so many lies you can take.”

Historian Jonathan Darman has written that a similar reckoning would be necessary for impeachment efforts to succeed, that “a few noble Republicans will have to simply listen to their consciences. They will have to come to Goldwater’s conclusion, that there comes a time when you choose patriotism over party. And that there are only so many lies you can take.”

But Elizabeth Holtzman, who was a prominent Democratic member of the House Judiciary Committee during the impeachment hearings, reads the history differently. “That wasn’t an act of patriotism,” she said in an interview this week with Yahoo News. “That was a political act. They were terrified that Nixon would not resign because the midterms [of 1974] were looming. Every day he stayed in office would have decimated them even more than it actually did.

“Will Senate Republicans vote to convict?” she asked. “I think that depends on the level of evidence here, but also the political calculation.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: