England in the 21st century may be an outpost of the United States, thanks to reverse cultural colonization, but Americans remain permanently poised for the latest British invasion. So the news in December 2010 that the novelist Martin Amis and his wife, Isabel Fonseca, herself a writer, had paid $2.5 million for an elegant brownstone in a genteel Brooklyn neighborhood sent a ripple of gossipy excitement through a city never so happy as when imported stars gobble up local real estate. A front-cover cartoon in The New York Observer, the peach-colored weekly, showed a white-clad Amis atop his front stoop, cigarette in hand, casting a baleful glance at younger Brooklyn literati, including Jonathan Safran Foer and Jennifer Egan, crowded behind an imposing fence. Amis's arrival, said Kurt Andersen, another Brooklyn writer, would be the "icing on the cake of the cool kids moving to Brooklyn"—even if in this instance the kid is a grandfather who will turn 63 in August.

Yet since last July, when he finally "pitched up onto American shores," as he puts it, Amis has been an all-but-invisible presence, save for an appearance, this past April, at the Cooper Union memorial service for his great friend Christopher Hitchens, who also happens to be the dedicatee of Amis's new novel, his 13th, Lionel Asbo: State of England. The book is an acidulous satire about a semiliterate thug who wins 140 million pounds in the lottery and soars to celebrity, becoming thoroughly at home in a luxury high-rise, where he joins "a recently imprisoned bratpack actor, an incensed fashion model, a woman-beating Premiership footballer."

Released in June in England, the novel met with mingled fanfare and abuse, the typical reception for an Amis novel, this time the complaints darkened by the perception that Amis has kissed off, and fallen out of touch with, the country he left. The dustbin empire he excoriates is at least a decade old—a place, one critic wrote, where "video games and social networks don't seem to exist, the national lottery is played by post, and a teenager composes a handwritten letter to The Sun's agony aunt instead of posting on the web."

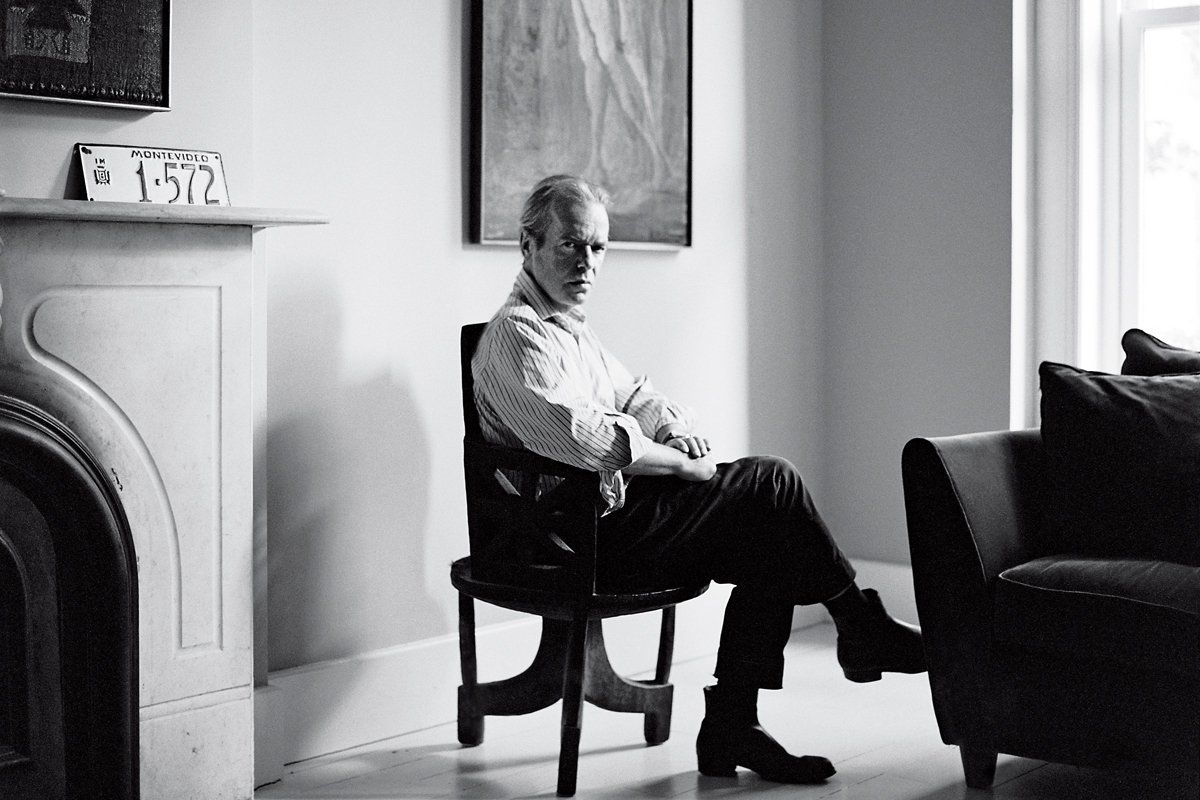

Just after Memorial Day, I visited Amis in Cobble Hill, on a quiet side street, 20 minutes by foot from the Brooklyn Heights Promenade and even closer to St. Ann's, the prestigious private school where Amis's two youngest children, Fernanda, 15, and Clio, 13, are enrolled. It was a blistering day, but the first floor of Amis's brownstone is as cool as it is pristine. It has white-stained wood floors, a fireplace, and on the walls, paintings by Fonseca's brothers, Bruno (who died in 1994 at age 36 ) and Caio. Copies of Asbo are stacked near the front door, in the hallway that leads to the large sunny kitchen. In sum, the most civilized of habitations for an author whose former reputation as man-about-town has subsided amid advancing age and the settled habits of literary industry.

Amis, trim and dressed in black, fetches two bottles of beer and seats us at a small round table. The angry response to his new book surprises him since he regards it as "celebratory," as the best serious fiction usually is. "I feel very uncrusading about England," he says. "For a long time it's been that way—affectionate amusement rather than any great frown. It's almost impossible to disapprove of the present without being reactionary, and to go on about how things have fallen off is an inherited formulation." This last assertion will startle British journalists, who in recent years have made a sport of compiling Amis's impolitic effusions—on subjects ranging from Islamists ("psychotic misogynists" and "homophobes") to England's elderly (candidates, he once jested, for euthanasia "booths").

An avowed enemy of England's gutter press, he might be expected to chortle over the Murdoch scandals. "I got a call from the police in England saying that my name and phone number were in the records, and [asking] did I want to take it further," Amis says. "There was no evidence they had hacked my phone." He is otherwise indifferent. "It's a media story. I'm interested in the effect of the media on the culture, but not in these internecine crimes. When you get [to the U.S.] it's confirmed what you long felt, that what England does in the world doesn't matter very much. To be interested in politics in England, I always felt, was to be interested in American politics."

On this last topic he has much to say. He has followed American politics closely since he reported on it for English publications 30 years ago. His account of the 1980 campaign for England's Observer emphasized the rise of the evangelical movement and its migration from theologically grounded "quietism" to activist politics, its pamphlets urging parents to "examine your child's library for -immoral, anti-family, and anti-American contents." But even as he mocked the -dollar-driven ministries of Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and Oral Roberts ("yes, Oral Roberts"), Amis cautioned his British readers not to "indulge our own vulgar delight in American vulgarity," adding that "to dismiss the beliefs of the evangelicals is to disdain the intimate thoughts of ordinary people." Today Amis marvels, like so many others, at how far the right has moved. In 2012 Ronald Reagan seems "a wild liberal," he says. "Imagine a British conservative party that was so far to the right of Margaret Thatcher."

Amis's fascination with American excess connects to his belief that in an empire "novels seem to follow the political power. In the 19th century, when England ruled the earth, the novels were huge and all-embracing and tried to express what the whole society was." This British "hegemony" waned with World War II and ended in the postwar years. "The English novel at that point was about 225 pages long and about career setbacks or marriage setbacks," he says.

By the time Amis and contemporaries like Julian Barnes and Ian McEwan were beginning to write, the "great tradition" looked depleted. "Uncannily, that power passed to the United States after the war and they started to write these huge novels"—they being Americans like Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, John Updike. Amis devoured them all, beginning with Mailer—his war novel The Naked and the Dead and his essay collection Advertisements for Myself. "I liked that loudmouth-y, great brazenness," Amis says. As a critic he has written indispensably on American fiction, especially the taboo-shattering Jewish writers—a breach of both literary and filial piety, since Martin's father, Kingsley, one of England's finest postwar novelists, was mildly anti-Semitic.

Martin Amis was all of 24 when his first novel, The Rachel Papers, was published in 1973. Its ferocious word-drunk hilarity and exuberant raunchiness owed much to Roth's Portnoy's Complaint. Amis's novel announced the arrival of a new British generation and also the advent of a new species of literary star, an alluring "bad boy," with Rolling Stones looks and a well-documented sex life. There was the string of in-crowd girlfriends and later a bitter feud with Barnes begun in 1994 when Amis switched literary agents from Barnes's wife Pat Kavanagh to the Manhattan "jackal" Andrew Wylie—who promptly landed him an $800,000 advance, unheard of in England, for his 1995 novel, The Information.

At the same time Amis reversed the current of trans-Atlantic influence. Just as the reinvented American pop music of the Beatles and Stones inspired American imitators in the 1960s and '70s, so Amis's American-inflected fiction seeped back across the ocean. In 1979 a young Yale graduate, Jacob Epstein, wrote a well-received coming-of-age novel, Wild Oats, that plagiarized dozens of passages from The Rachel Papers. Amis tallied the verbatim thefts in an essay for the Observer and concluded, "Epstein wasn't influenced by The Rachel Papers. He had it flattened out beside his typewriter."

Epstein, like Amis, had the literary gene. He was the son of Jason Epstein, vice president of Random House, and Barbara Epstein, coeditor of The New York Review of Books, the august biweekly. Jacob Epstein, who apologized to Amis, stopped writing novels (he became a successful TV writer); and the Review, which had applauded Amis's first novel, thereafter ignored all his subsequent work, shunning him for more than 30 years—until Barbara Epstein's death in 2006. "Water under the bridge," Amis says today. "It ended when [Epstein] ended." And indeed the Review has since paid him respectful attention.

All this commotion enlarged Amis's celebrity but obscured the seriousness of his continued aesthetic quest. One who did take notice was Frank Kermode, one of England's most distinguished literary scholars, who judged Amis a -"prodigiously gifted" writer. Yet Amis has yet to win the coveted Booker Prize, unlike his contemporaries Barnes, McEwan, Salman Rushdie, and Graham Swift. But now perhaps, as Amis enters his new phase as literary expatriate, it's possible to see that for some 40 years, as novelist and critic, he has been administering a kind of dual electroshock therapy—to the English novel and to English society, trying to awaken both from lethargy, or catatonia.

This is the hidden drama in Amis's latest report on the "state of England." However appalling a creation "the brutally generic" Lionel Asbo may be, he becomes "a national symbol of ... peculiarly English intransigence in the face of relentlessly blighted hopes." And the reason is clear. He meets those blighted hopes with energy, malignant but real. And this time Amis offers something new—a genuinely romantic idealist, Lionel's nephew Desmond, who, via literature and fatherhood, discovers a fresh exit from what Amis has described, in his classic Money, as the slum "etiquette of the moneyed and mobile yob—be unpleasable, take it all as your human right."

The British may have heard enough. But for American readers, weighing the costs of "diminishing expectations" in the new millennium, Amis's peephole picture of a great nation in decline, its inhabitants like ICU patients gnawing at their sutures, will seem painfully relevant.

Before I left Amis to his dinner and his family, I asked him about one of the many literary references in London Fields (1989), the apocalyptic novel that may be his masterpiece. At one point, a character paraphrases a remark of Saul Bellow's that since "the real modern action" is in America, it is the only place to be. Does the formulation still hold at a time when the U.S. has developed its own case of post-imperial anxiety?

Possibly, Amis said, though there's a major difference. For the British "the ideology that we call PC or level-ism actually sweetened the pill of decline. It was saying, 'You haven't got an empire anymore, but you shouldn't have had an empire in the first place. We don't like empires.' It sort of soothed our brow. There's no great fury about decline in England." Americans, he thinks, will react differently. "They're not going to be docile and stoic like we were." What should we expect instead?" Amis's replies are normally prompt, but this time he paused over his beer. "A fair amount of illusion."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.