The Political Question of the Future: But Are They Real?

What happens when live-streams become the new fireside chat

The bully pulpit is getting smaller. Open your phone, and there’s the Democratic rock star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the newly elected representative from New York, live-streaming on Instagram as she whips up some mac and cheese. Now it’s a video of maybe–presidential hopeful Beto O’Rourke pouring a batter of “slime” with his daughter on a well-lit kitchen island. Now it’s Senator Elizabeth Warren, who recently announced she would run for president, making straight-to-camera small talk as she pulls from a beer bottle on Instagram Live.

This is the future of political rhetoric: handheld, streaming, and dappled with DIY lighting.

Politicians pressing the record button as they futz about the kitchen might seem like a pitiful degradation of political communication—from “four score and seven years ago” to four scoops of seven-grain bread dough. But as silly as it sounds, the rise of live-streams and clapback memes is just the latest step in the long evolution of political speech. In the past century, such speech has become ever more casual as it has migrated from soapboxes to smartphones. Politicians who have mastered the patois of new platforms have consistently held an advantage over opponents who failed to appreciate the power of those technologies.

Politics is downstream from culture, and political culture is downstream from media technology. The way the public consumes political speech affects the substance of the speech.

To take things all the way back, George Washington’s first inaugural address began like so:

Among the vicissitudes incident to life, no event could have filled me with greater anxieties than that of which the notification was transmitted by your order, and received on the fourteenth day of the present month.

Practically no commoner would have understood Washington’s wordy preamble. But he had little reason to care, since practically no commoner would even have heard it. The address was delivered—or mumbled, reportedly—at Federal Hall in New York City, to an elite and overwhelmingly white and male audience, who presumably shared Washington’s penchant for impenetrable diction.

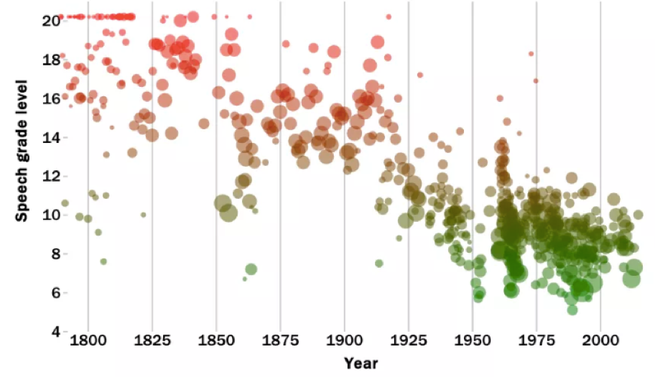

As late as 1900, the typical presidential speech employed college-level complexity. By the 1930s, that complexity had fallen to high-school level, and today presidential speeches are simple enough for sixth graders. That’s according to a recent study that analyzed hundreds of presidential speeches, from Washington’s to Barack Obama’s, with the Flesch-Kincaid test, a U.S. Navy measure used to code the readability of military instruction manuals. More specifically, presidential rhetoric suddenly shed its sesquipedalian sheen in the early 1900s. Er, it got simple real quick.

What happened? Twin revolutions in American suffrage and communications tech. In 1913, the United States added a Seventeenth Amendment, which allowed for the direct election of senators; and in 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote. Over the next decade, a new invention, the radio, entered more than 50 percent of U.S. households, allowing presidents to reach audiences several orders of magnitude larger (and more diverse) than they were used to. As the electorate became more populous, political speech became more populist.

Since the turn of the 20th century, successful presidents have recognized that mastering emerging communications technology was central to reaching potential voters, and therefore to their political fortunes. The first radio address was delivered by Calvin Coolidge on December 6, 1923. The New York Times estimated that 1 million Americans heard the speech, predicting that Silent Cal’s voice “will be heard by more people than the voice of any man in history.” But it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who realized that radio’s power wasn’t sheer amplification. It was something more subtle: intimacy at scale. His fireside chats helped endear him to a populace on the brink of economic ruin. Similarly, while Dwight Eisenhower was the first president of the television age, it was the telegenic John F. Kennedy who dominated the medium by proving that when it comes to video, every contest is, at least in part, a beauty contest.

In the 21st century, many people have cut the cord and switched from pay TV to social media as their main source of news and entertainment. Trump’s laconic insults and monosyllabic yelps proved a perfect match for Twitter. Now we’re seeing what sort of political performances are the right fit for Instagram, which has an even larger reach.

Unlike television, YouTube and Instagram aren’t natural homes for the glitziest, most high-production-value performances. As with radio, their power is intimacy at scale. Many of the most successful YouTube and Instagram influencers are masters of slangy verisimilitude. The message is, “Watch me, and see a version of yourself.”

Ocasio-Cortez may be to the left of the 2019 electorate, but her Instagram activity tells the single most conventional American story: upward mobility. Some politicians would require a phalanx of writers and marketing experts to communicate a personal narrative as clear as the one Ocasio-Cortez conjures with nothing but a smartphone: A young Latina woman goes from bartender to congressional superhero while remaining true to her cheap-pasta roots. With more than 1 million followers on both Instagram and Twitter, she doesn’t rely on the machinery of the Democratic Party or cable-news networks to reach a large audience. If JFK and Ronald Reagan were television stars, social-media-savvy politicians such as Ocasio-Cortez have a chance to become something more: a television network, with the ability to program around both the news media and the party apparatus.

Politicians of all stripes now have an opportunity to turn their smartphones into production studios of personal glorification. But just as not all presidents have been equally talented on radio and TV, not all politicians come to live-streaming with aplomb. (Among the vicissitudes incident to life, imagine the anxieties that the requirement to transmit by Insta would have given George Washington.) Warren’s foray into kitchen live-streaming was less than fluent. “I’m gonna get me … um, a beer,” Warren said in her last video, before disappearing off-camera, where she seemed to spontaneously discover a surprise visitor: her spouse. “Oh, hey. My husband, Bruce, is here.” Bruce entered from stage right, waved demurely, and slid quickly back out of the frame, with the enthusiasm of a young child dragged against his will to speak on the phone to a distant relative.

It’s tempting to say Warren simply goofed by making a shoddy video. But the truth is more complex. New communications protocols don’t just change the way politicians speak; they change the way voters evaluate political speech and, by extension, the portfolio of talents that voters seek in a leader. The age of television rewarded the skill of capturing an audience from a podium. But politicians who thrive on social media will have to master a different suite of skills, such as mimicking the internet’s more naturalistic, self-aware style in a medium where the distance between star and viewer is closed, and where all viewers are conscious of themselves as a collective audience.

Is instagram politics good for democracy? Who knows. Ocasio-Cortez, a preternaturally gifted digital communicator, has already used her star power for uncommon ends, from gleefully skewering Republicans to tweeting about how a Harvard orientation for incoming lawmakers turned out to be a lobbyist meet and greet. To her fans, she is an unvarnished idealist exposing the government from within—like a muckraker who’s been named to the board of a meatpacking plant. By casting herself as Washington’s in-house critic, she could increase public understanding of the place and inspire young leftists to join her in the fight to fix a broken system. Her tweets and messages about legislative meetings offer a rare, almost documentarian glimpse of Washington’s backroom operations. That could give voters a sense of participation in a system they no longer trust.

But the age of smartphone politics could pave the way for a new crop of demagogues who are as adept at mimicking “intimacy at scale” as the 20th-century autocrats were at captivating crowds from a podium. As the performance of honesty becomes more central to campaigning and governance, it could magnify already unhealthy debates over authenticity. Horse-race coverage would merge with theatrical criticism, diminishing political discussion to the asking and reasking of the same fundamental, unfalsifiable question: But are they real? But are they real? But are they real?

This article is part of “The Speech Wars,” a project supported by the Charles Koch Foundation, the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press, and the Fetzer Institute.