Slowhand: The Life and Music of Eric Clapton is my eighth rock biography since Shout! The True Story of the Beatles in 1981. It left me feeling more than ever that writing books about such people is no job for a grownup and determined never to be talked into another one.

I had intended Shout! to stand alone, but it started a chain reaction that has kept me chained ever since, with only temporary breaks for novels, short stories, plays, TV documentaries, musicals and journalism.

Researching the Beatles provided an irresistible flying start to a biography of the Rolling Stones, whose story was so closely bound up with theirs. Afterwards, it was almost obligatory to “do” Buddy Holly, who established the rock band concept with the Crickets, and first inspired John Lennon and Paul McCartney to try songwriting, as they in turn inspired Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and hundreds of other musically unschooled young Brits. Then there was no escaping Elton John, who was discovered by the Beatles’ music publisher, Dick James, and took to wearing outsize spectacles like Holly although his eyesight was normal.

Eric Clapton adds yet another link as his best friend was George Harrison (which didn’t stop him going off with Harrison’s wife) and he was the only outsider ever to be an unofficial member of both the Beatles and the Stones.

Had I pursued a career as a novelist, as I originally intended (I was on the first Granta best young British novelists list) it’s doubtful that I could have reached the audience – or level of publishers’ advances – rock biography has brought me. As well as in the UK, US, Australia and throughout Europe, my books have appeared in countries including Russia, China, Japan, Estonia, Macedonia, Mexico and Brazil. I like to think of Cossacks on the windy steppes arguing the rival merits of Ringo Starr and Charlie Watts as drummers, or Amazonian tribes poring over the subtext to Norwegian Wood.

At the same time, I’m aware of being thought not quite respectable by the literary establishment. When the time comes to promote a new book, I find myself spurned by the big festivals such as Hay and Oxford, and consigned to the backwoods of Porlock and Port Eliot.

I can hardly complain, since no one could think less of so-called “rock writing” than I do. Frank Zappa memorably defined pop music journalists as “people who can’t write preparing articles about people who can’t think for people who can’t read”. But even people who can write – such as Salman Rushdie or Martin Amis – tend to reveal a vein of prattishness on this particular subject, gushing like the most besotted fans about “what David Bowie” – or whoever – “meant to me”, and almost always trotting out that tired old phrase “the soundtrack of my life” as if it were newly minted.

Writing about rock seems to be considered a soft option whereas to do so in any objective way is a hellishly difficult task that each time has me tearing out what remains of my hair. One must constantly walk a tightrope between enthusiasm and detachment, proper recognition of talent and laughable hyperbole. One must try to convey what music actually sounds like (an exercise at which even my two greatest literary heroes, EM Forster and F Scott Fitzgerald, failed miserably with Beethoven and jazz respectively).

One must get in all the dreary stuff about record sales and chart placings while retaining a sheen of literacy, ever seeking new and interesting ways of saying: “The single went to number three in Billboard’s Hot 100.” One must relate one’s heroes to world events without sounding like the Rock’n’Roll Years audiotapes they used to play on BA flights: “It was 1961. In Berlin, they were building a wall. But that didn’t stop Bobby Vee having a hit with Take Good Care of My Baby.”

For me, Albert Goldman’s notorious biographies of Elvis Presley and John Lennon remain exemplars of how not to do it – with their vestigial research, ludicrous fabrications and, above all, snobbish contempt for their subjects. To write an 800-page book about somebody one despises is surely a sublimely pointless exercise. Admittedly, some rock stars have been monsters on a par with the nastier Roman emperors; still, come what may, you have to love your monster.

Only one of my eight biographies even came close to being authorised in the conventional way, that is, when a subject talks directly to a writer and vets the material before publication. But others have been endorsed retroactively or approved by the back door.

I had only just completed Shout! in December 1980 when John Lennon was murdered. Five months later while I was in New York publicising the book, Yoko Ono saw me on television and phoned me there at ABC’s studios. “What you just said about John was very nice,” she said. “Maybe you’d like to come over and see where we were living.” That afternoon, I was at the Dakota Building, being shown round their vast, white, seventh-floor apartment that was still just as Lennon had left it, his guitar hanging above his bed and all his clothes back to the 1960s on revolving racks like some petrified boutique.

When I was researching Elton John, my subject was undergoing multiple detoxifications and was unavailable for interview. But after the book came out, he phoned me, said it was “pretty accurate”, invited me to tea and, over Earl Grey and chocolate cake, virtually dictated a postscript chapter about his rehab.

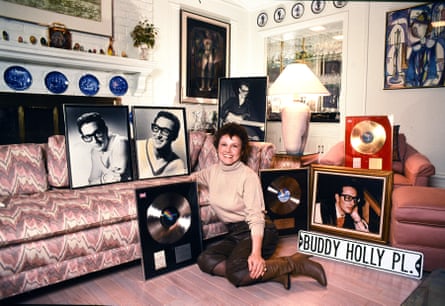

My longest pursuit was of Buddy Holly’s “widowed bride”, María Elena, that poignant presence in Don McLean’s song American Pie. It took me a year even to get her on the phone and when at last I did so, her opening line was: “All writers are scumbags.” She finally agreed to see me in Dallas, Texas, on condition we met in her lawyer’s office – and I paid for the lawyer’s time. However, when I got there she relented and the two of us just went off (minus her lawyer) to lunch.

The strangest case was that of Paul McCartney, whom I admit to having misjudged in Shout! - and who thereafter referred to the book as “Shite!” Yet he let me interview him by email for John Lennon: The Life and when I proposed a companion volume about him, came back with his “tacit approval” in a personal message less than two weeks later.

On the Lennon project, I found myself first authorised, then deauthorised. For three years, I had Yoko’s total cooperation: not only hours of revelatory interview with her but also with their son Sean and her daughter by a previous husband, Kyoko. The only condition was that she would read my manuscript and, if she liked it, would contribute a foreword (which, truth to tell, the publishers were rather dreading).

I sent the unedited text to her and initially the signals that came back were positive. The final bit of access I hoped for was to read John’s diary, kept deep in the vaults of the Dakota Building. Some weeks later, I received a friendly invitation to drop by for this very purpose. As I walked across Central Park to the Dakota, a thought suddenly popped into my head: “Suppose she’s waiting for me with a lawyer?”

She was waiting with two lawyers. She’d decided the book was “mean to John”, and so was withdrawing her quotes and those of Sean and Kyoko. For two highly unpleasant hours, seated around the same kitchen table where John used to drink tea and smoke Gitanes, she and the lawyers tried to pressure me into turning over the interview tapes. Also present was an unidentified woman whose role was unclear until Yoko shouted, “How could you say that John masturbated?” – which she’d mentioned with amusement during our interviews.

At this, the mystery woman went “Ugh!” with a theatrical shudder, and I realised she was Yoko’s personal shudderer.

Under our agreement, Yoko had no prerogative to withdraw her quotes, let alone demand the tapes. Nonetheless, during the 12-month lead-up to publication, I checked the emails every day, dreading a legal onslaught from her. But it never came.

This summer, I did my best not to listen when friends pointed out that 2020 would mark the 50th anniversary of Jimi Hendrix’s death and that no one had ever properly chronicled his too-brief career nor investigated the murky circumstances in which he met his end. I was doing fine until our milkman in north London mentioned how, in another life as a painter and decorator, he and his brother had done up a flat for Jimi and what a “lovely fella” their client had been.

So now I’m researching Hendrix, with thoughts of Michael Corleone vainly trying to break away from the mafia in The Godfather Part 3: “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.”

Slowhand: The Life and Music of Eric Clapton is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion