When a major weather event threatens, one of the first things most Americans do is try to make sure that all their vehicles have a full tank of fuel. That spike in demand for gasoline and diesel fuel strains the delicately balanced supply chain, and consumers often find that their local gas station has run out of fuel.

For some idea of the scale of U.S. gasoline consumption, remember that Americans burn about 400 million gallons of gasoline — that is a little less than 10 million barrels — every day of the year.

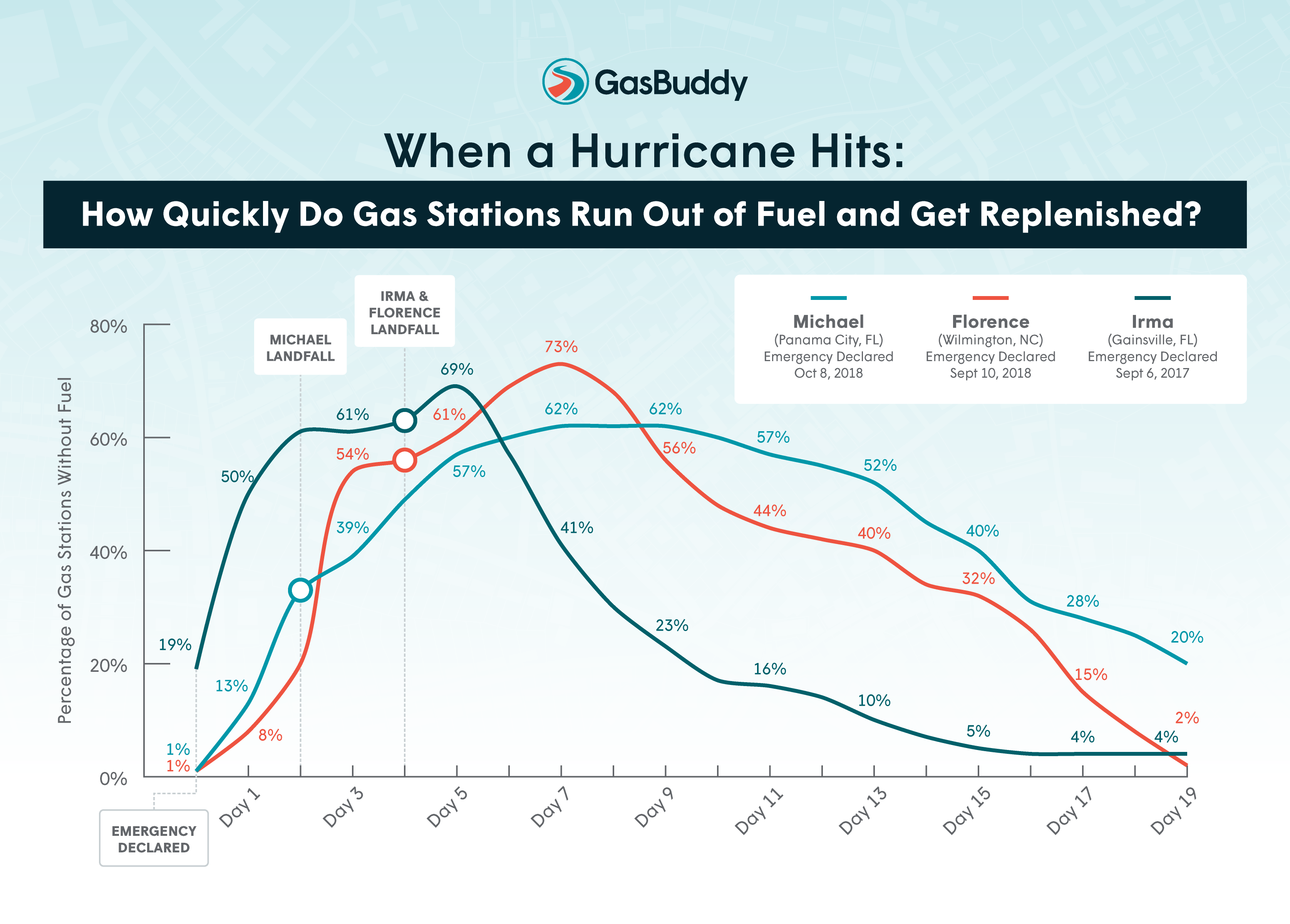

GasBuddy, a source of real-time gas prices based on consumer-reported data, analyzed data it has collected over the years on how quickly and to what degree gas stations both run out of and refill fuel supplies. The firm uses the day when an emergency is first declared as its starting point, but note that in at least one case, nearly 20% of local gas stations were out of fuel on the day when officials declared the emergency.

Unpredictable weather disasters can take many forms, from hurricanes and blizzards to tornadoes and raging wildfires. How quickly people get help, including gas, medicine, and provisions, depends on several factors. And some states are better equipped than others — these are the best and worst prepared states for weather emergencies.

The following chart shows how quickly gas stations ran out of fuel when disasters were declared for Hurricanes Irma, Florence and Michael in September 2017, September 2018 and October 2018, respectively.

“Most areas begin to see improvement [in fuel availability] within a week of landfall of a major hurricane,” notes Patrick DeHaan, GasBuddy’s head of petroleum analysis. Hurricane Michael caused such devastation in the Panama City area that more than 50% of the area’s gas station still had no fuel 13 days after the disaster was declared, compared to about six days for Hurricane Irma and nine days for Hurricane Florence.

Proximity to a refinery matters when it comes to replenishing gas station tanks. Neither Florida nor North Carolina has a refinery in the state. The difference between the replenishment times for Michael and Irma was due to efforts already underway to refill Florida’s tanks by using barges to haul refined fuel to the state.

Gasoline travels from a refinery to a bulk terminal (sometimes called a “rack”) from which it is loaded on the familiar gasoline transport trucks and hauled to underground tanks at gas stations. If roads are inundated or otherwise damaged, the delivery trucks either have to travel further to detour around the impassable roads or wait until the usual route is open again. If pipelines from a refinery to the terminals are damaged, it can take even longer to replenish supplies at local gas stations.

DeHaan also commented on the complexity of the gasoline supply chain: “So many factors go into supply and demand before and after a major storm — things like location, infrastructure, expected path, refinery location, power supply — that make it impossible to predict the exact moment when fuel networks are in the clear or begin to recover, but we definitely have seen fuel supply becoming a larger focus for government during hurricane season.”

Extreme weather events are becoming more common and somewhat more unpredictable. Some of the most powerful storms — Hurricane Andrew in 1992, for example — hit during a fairly slow hurricane season. These are the most powerful hurricanes of all time.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.