Climate change worries take backseat in hot real estate market

The real estate market has bounced back from the housing crisis, but rising sea levels could leave millions of homeowners underwater again -- this time, quite literally.

The last housing crisis wiped out billions of dollars in home equity and left millions of Americans underwater on their homes — owing more on their mortgages than their properties were worth. But while the real estate market has bounced back, rising sea levels in the coming decades could leave millions of homeowners underwater again — this time quite literally.

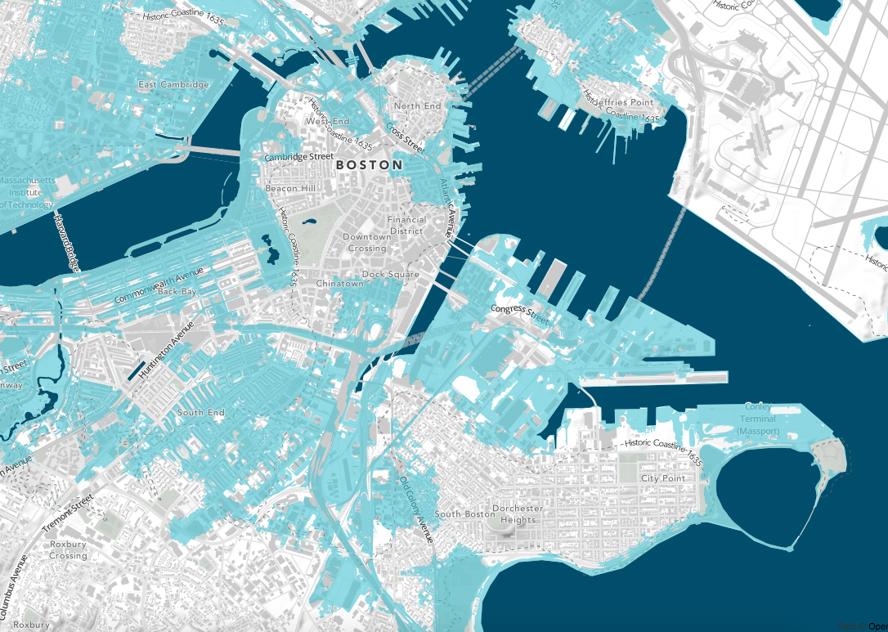

As the effects of climate change intensify, Boston and many other coastal communities in Massachusetts are particularly vulnerable. The City of Boston published a report last year detailing how the climate here is likely to change in the 21st century, and the forecast is troubling. High tides will get higher, waves may grow more forceful, and even weaker weather systems will produce damaging tidal surges — to say nothing of the havoc caused by more intense storms.

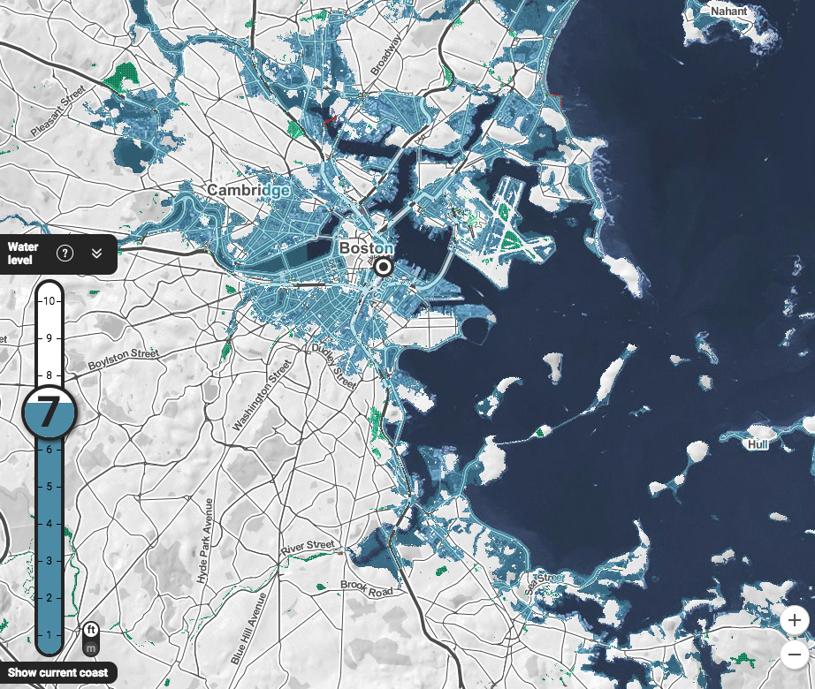

While long-term projections hinge heavily on future greenhouse gas reductions, even a drastic cut in carbon emissions would probably leave Boston Harbor at least 2 feet higher by the end of the century; assuming the status quo, we’re looking at up to 7 feet of sea level rise locally by 2100. (Regardless, a 1.5-foot increase seems likely by 2050.)

You can search flood maps by address on FEMA’s website at msc.fema.gov. Other helpful resources include Climate Central’s Risk Zone map at ss2.climatecentral.org and Sasaki Associates’ interactive, Boston-centric Sea Change map at seachange.sasaki.com/map.

And though the report is specific to Boston’s future, the changes will affect communities all over the Commonwealth. Many more of us will be forced to get more familiar with the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) flood insurance program.

If you’re busy touring open houses this weekend, this may sound like a tinny alarm bell from a distant, dystopian future; after all, climate change is a long-term crisis advancing in slow motion. But house hunters would do well to think long term. A home isn’t just the biggest purchase most people ever make — it’s also likely to be among their most enduring life decisions. The average home buyer stays put for 13 years, according to a 2013 study by the National Association of Home Builders; in 2011, more than a third had been in their homes at least 30 years.

Meanwhile, 66 percent of the people surveyed in a recent Gallup poll said they worry about climate change “a great deal’’ or “a fair amount,’’ but as home buyers gear up to make the biggest purchase of their lives, most don’t appear to be taking it into consideration. In Massachusetts, we’re buying up flood-prone houses and waterfront condos at record prices.

The red-hot real estate market probably isn’t helping. “Three years ago, people would snub their nose at a flood insurance house,’’ said Jim McGue, owner and broker at Granite Group Realty in Quincy. But in a tight market with so few homes for sale, McGue said, buyers are willing to take their chances and suck up the costs of flood insurance, which in Massachusetts averaged $1,198 in 2016.

“I try to discourage it, because once FEMA’s in your pocket, they’re not coming out,’’ McGue said. If a property lies within a special hazard flood area, lenders will require you to purchase flood insurance. And while buyers will overlook that added risk and expense in a hot market, a flood plain home has “significant baggage’’ in a downturn, he said.

Nela Richardson, chief economist at the real estate brokerage Redfin, agrees that buyers just aren’t reacting to climate change. “What we see, especially in the Boston area, is a lot of those coastal properties are high-end real estate, and they sell at a premium,’’ she said. “I think the psychology is, It’s too far away for me to worry about it.’’

Boston-area buyers may also be placing some faith in science and local leadership. Governor Charlie Baker has ordered climate change vulnerability assessments for the entire state and asked his agencies to prepare resiliency plans, said Paul Kirshen, academic director of the Sustainable Solutions Lab at the University of Massachusetts Boston who worked on the Climate Ready Boston report. Meanwhile, city officials are considering adaptation measures that could include a giant sea wall protecting Boston Harbor from Hull to Deer Island.

However, there’s only so much communities can do to fend off a global problem. What should Massachusetts home buyers know and do to protect their investments?

“First and foremost they should be asking questions — of the realtors, of the seller’s agent — and really understanding what the risks are,’’ Richardson said. “Study the FEMA flood maps and know whether you’re buying in a low- or high-risk zone. And it’s important to know those maps change.’’

If a property looks as if it requires flood insurance, McGue said, ask the listing agent for a copy of the elevation certificate and whether the existing flood policy can be transferred to a new owner at the same rate. And do your own due diligence. “Brokers get cute,’’ McGue said. “They’ll say, ‘Owners do not pay flood insurance.’ You see that on [the Multiple Listing Service] all the time.’’ That doesn’t guarantee the property isn’t in a flood plain, he explained; they may have just paid cash, so make sure there’s actually a mortgage on the property.

You might also ask neighbors whether they ever get water after a storm, and do some detective work on your own. “Look under the cellar stairs,’’ McGue added. “If there’s water in the basement you’ll see it there; you’ll see stains where maybe they didn’t repaint.’’

Raising a flood plain home is another possibility, said Peter MacDonald, vice president of sales and marketing at Murray & MacDonald Insurance Services Inc. in Falmouth. “Along Surf Drive in Falmouth, there are a bunch of houses that were damaged during Hurricane Bob, and they were all rebuilt on pilings. I think that’ll be the new normal a few years from now,’’ he said.

It can cost upward of $70,000 to lift a home onto pilings, but if you can elevate the lowest living space above the flood level — including all mechanical systems like boilers, hot water heaters, and air-conditioning units — it can dramatically reduce your flood insurance premiums, MacDonald said. “It’s going to pay for itself in terms of flood insurance, and it’s going to make the home more marketable because it opens it up to people who need a mortgage.’’

Richardson, however, suggested buyers in risky areas get flood insurance even if it’s not required, saying “it would be a worthy protection of your investment.’’ Federal flood insurance covers only up to $250,000.

With all that said, there are still no guarantees, especially on the famously shifting sands of Cape Cod. “Land movement is excluded; earthquake, erosion, that’s not covered on your insurance policy,’’ MacDonald said. “If this stuff happens to you, you’re screwed.’’

“Also consider,’’ Kirshen added, “if there is a flood, will you be isolated by the flood waters? Will the roads and public transportation network be threatened?’’ If that strikes you as alarmist, consider that just a 3-foot rise in ocean levels would submerge 48.5 miles of roadways on Cape Cod and leave about 160 more miles disconnected from the network, according to the Cape Cod Commission. And a 2015 study out of Princeton and Germany’s Potsdam University estimated that our total emissions to date are already enough to lock in 1.6 meters (about 5 feet) of sea level rise, though probably not for many, many years.

It raises the question: Will some areas simply become too risky to live in? Sean Becketti, vice president and chief economist at the government-sponsored mortgage giant Freddie Mac, warned in 2016 that climate change could present a bigger threat than the housing crisis. Noting that most of homeowners’ wealth is locked up in their home equity, he wrote, “If those homes become uninsurable and unmarketable, the values of the homes will plummet, perhaps to zero. Unlike the [housing crisis], homeowners will have no expectation that the values of their homes will ever recover.’’ What’s more, Becketti said, whole communities may vanish.

One extreme solution is a buyback program, where the government pays homeowners to move away from the coast and into less risky areas. Armando Carbonell, senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, studied policy responses in New York and New Jersey after Superstorm Sandy hit in 2012. “We got very interested in this idea of strategic ‘retreat’ on coasts,’’ he said. “It’s a bad word and people don’t like to use it, like we’ve been defeated,’’ Carbonell said. “But in some cases it’s a very sensible thing, and it will reduce costs and loss of life.’’

Carbonell recognizes that wholesale relocation is a tough sell. But as flood hazards along coasts and rivers become a bigger threat to life and property, he said, “Buyouts need to be part of the conversation. There are some places we simply shouldn’t rebuild.’’

If you’re on a house hunt this spring, researching school districts and commute times, perhaps there’s one more consideration to keep in mind — whether there are areas where you shouldn’t be buying in the first place.

Jon Gorey is a freelance writer in Quincy. Send comments to [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @jongorey. Subscribe to the Globe’s free real estate newsletter at pages.email.bostonglobe.com/AddressSignUp.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com