"Come and take it!"

Texas as an American state, like Texas as a republic before that and Texas as a Mexican state before that, survived only because armed civilians did what their government could not do—keep them safe, keep them alive. Without guns, there would be no Texas.

The first Texans had self-defense in their DNA because Mexico back then was a continuing carnival of revolutions and counterrevolutions. The far northern Mexican states, including Texas, contributed little economically to the central government, and their defense was expensive, so the settlers were often left on their own. The most common danger arose because the fight to take Indian land that so greatly inconvenienced General George Armstrong Custer on the Northern Plains was just as deadly on the Southern Plains. The Comanches, like other Texas Indians, quickly adopted the gun culture of the settlers and took up firearms as swiftly as they could trade for or steal them.

The Texas Revolution, like the American Revolution before it, was touched off when troops from the mother country were sent to repossess arms given to a militia for defense against Indians. While the redcoats at Lexington Green came to clean out an entire armory, the Mexican army was sent to Gonzales, Texas, to retrieve just one small cannon lent for warding off Comanches. That cannon is now represented on a flag iconic to the modern militia movement, along with the reply from the citizens of Gonzales: "Come and take it!"

That defiance—and that love of firepower—lives on.

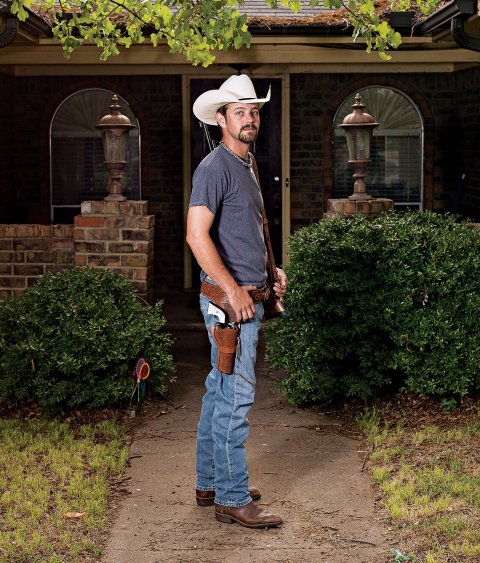

The Texas Cowboy

The Texas stereotype of the cowboy hat and the pistol, like all stereotypes, has some truth to it. When I was an elected judge in Austin, I appeared at a candidate forum with the incumbent sheriff. A resident on the other side of Lake Travis from Austin asked him about response time.

"Well," the sheriff smiled sheepishly, "we try to get to it the same day."

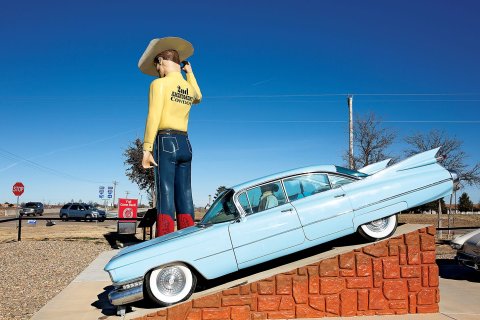

The sheriff was wearing a wide-brimmed hat, as was the man who asked the question. John B. Stetson called his hat "Boss of the Plains," and it was a pricey fashion statement, but it was based on the same practicality as a cheap straw sombrero. Mesquite trees don't throw a lot of shade and cottonwoods throw theirs only near water. To work outside in these climes, you bring your own shade.

That stereotypical hat was born in practicality, as was the stereotypical pistol. A rural sheriff needing to summon a posse has no armory. He expects the volunteers to bring their own guns, pistols or long guns. The last land battles in the U.S. with foreign troops were on Texas soil during the Mexican-American War in the 1840s, but the tradition of an armed citizenry goes back to Stephen Austin's settlement in 1825.

The tradition endures, even as the threat level has been dialed way back. In 2010, then–Texas Governor Rick Perry was out jogging when, he claimed, a coyote menaced his dog. Perry produced his Ruger .380 semi-automatic with a laser sight from wherever he kept it while wearing a T-shirt and jogging shorts. There's something "only in Texas" about the thought of that red laser dot moving across the coyote's body just before Perry squeezed the trigger.

Sturm, Ruger & Co. immortalized the feat when it offered a pistol just like Perry's that said on one side of the barrel "Coyote Special" and on the other side "A True Texan."

The Republic of Texas purchased 180 early Colt revolvers intended for the Texas Navy in 1839, but some came into the hands of the Texas Rangers, a paramilitary force originally formed to be a body of white men just as tough as the Indians and therefore able to kill the many Indians who objected to white settlements. Ranger Captain Samuel Walker used one of the early Colts, and his experience resulted in Walker and Samuel Colt redesigning the gun in 1846. The Walker model was introduced in 1847. At 4 pounds, 9 ounces, it was the original .44 Magnum handgun. The original black powder Walker Colt is a collector's item today. To this day, Texans who can afford a .44 Magnum might boast that their choice of sidearm is "a holster full of whoop-ass."

'Laboratories of Democracy'

The U.S. had long been a bicoastal power when I joined the military in 1964. The militia had become the National Guard, but there was a standing Army, Navy and Air Force. Military service in those branches forced—or enabled—young people from all over the country to interact. I was strolling through Luling, Texas, about a year into my hitch with a friend from Air Force boot camp. Luling's population was swelled by the annual "Watermelon Thump," an excuse to celebrate local produce and even enter a seed-spitting contest.

I had never visited a city larger than Dallas (if driving through constitutes a "visit"), and boot camp had brought me to San Antonio, a place with almost twice the population of my idea of big back then, which was Oklahoma City. My companion had been born and raised in a big northeastern city that he left for the first time to go to boot camp. We were looking for a way to beat the summer heat when he stopped walking so suddenly that I bumped into him, and he said, "My God, look at that! Should we find a cop?"

"Look at what?"

"That gun. Right out in public!"

He was pointing at the most common ride in Texas then, a Ford F-100 pickup truck. In the gun rack behind the bench seat was a small shotgun and a big rifle. He asked if that display of weapons was legal. What, I had to ask, was the purpose of a gun rack if not to transport a gun?

We went closer and saw the truck was not locked, and the windows were down to keep the interior cool for a big brown dog who looked pretty friendly. Not locking the truck with all the strangers in town seemed to me a bigger deal than having guns in plain sight, but you don't leave a dog you love or even like in a closed truck in the Texas summer.

The rifle was a Winchester 30.06, commonly used for deer hunting or what we called "varmints," which were understood as wildlife likely to molest livestock. The shotgun was a little .410 of indeterminate make—the most common use would be dispatching rattlesnakes. I added that most of the .410s I had seen were owned by kids.

A child owning a firearm gave him a culture shock as great as the one he got from this truck parked on a public street with visible guns in it. He had just gotten his jaw back up to normal position when the cowboy who owned the truck showed up. "Howdy, boys," he said as he offered his dog a stick of beef jerky. "Y'all keeping the Air Force out of trouble?"

We exchanged small talk until he drove off, then bought a couple of tall watermelon aguas frescas and sat down to compare notes about guns. He was, in the parlance of my region, a "Yankee." I understand that is not what those folks call themselves, but the point is I knew we had cultural differences and so did he. Guns, to him, meant pistols. A few people he knew kept hunting rifles, but he claimed to have never seen a shotgun. Pistols required a permit in his part of the country, and his dad owned a .38 revolver, which my companion had fired once at an indoor shooting range. The first time he fired a rifle was in boot camp. There were neighborhoods in his city, he explained, where there were few pistol permits but everybody had a pistol. Those neighborhoods, he assured me, were not tourist destinations and were avoidable by anyone the least bit prudent.

I told him that if I wanted a pistol, I didn't even need to find a gun shop—most hardware stores in Texas carried them. He was appalled. He must have thought things had tightened up after Lee Harvey Oswald got an Italian military rifle by mail order. It had been 19 months since Oswald changed the course of history 250 miles up the road in Dallas. I explained that I grew up with the Sears & Roebuck "wish book" that offered British Enfield military rifles either in original condition or spiffed up to compete with the sporting rifles offered on the same page.

While we sat under a shade tree sipping aguas frescas and taking turns scandalizing each other with gun stories, I was getting my first exposure to the conceit that the 50 states were what Louis Brandeis called "laboratories of democracy." The idea is that different states make different rules about the same matters, and the nation can compare the results to see what works.

I was also experiencing the upside of near-universal military service: the epiphany that a big country contains very different attitudes and values, but those differences do not mean people who think differently are therefore inferior.

'Let's Get Him'

I found my friend's squeamishness about a deer rifle laughable. My amusement lasted a little over a year, until August 1, 1966, when Eagle Scout, ex-Marine and engineering student Charles Whitman walked into an Austin hardware store and bought an M1 carbine, two extra magazines and eight boxes of ammunition. He then stopped at Sears and bought a 12-gauge shotgun. At a gun shop, he picked up four more magazines for the carbine and six more boxes of ammunition.

Whitman packed all this into a footlocker with enough food to last two weeks and rode the elevator up the University of Texas clock tower, which had an observation deck. He killed the tower receptionist and sprayed a family that came upon him with a shotgun. From his sniper perch on the observation deck, his first victim was a pregnant woman—more precisely, her baby. He made many more difficult head shots in the next 96 minutes, firing down at strangers from his 28th-floor aerie. He killed 13 people immediately, and two died later from their injuries. He also injured 31.

Austin police officers were armed only with pistols and shotguns—neither one was useful at the distances involved, but when the shooting started, students disappeared into their dormitories or apartments and returned with their deer rifles. Police officers went home to retrieve their deer rifles. The ensuing gun battle offered plenty of time for TV news to get their cameras in place.

At first, there were only Whitman's muzzle flashes. Then, return fire began as an occasional shot and then a couple more coming in from other angles. Eventually, the return fire swelled to a fusillade every time Whitman's head popped up. Novelist Ann Major, who was a UT student then, told Texas Monthly , "It seemed like every other guy had a rifle. There was a sort of cowboy atmosphere, this 'Let's get him' spirit."

In August 2006 in Texas Monthly, Bill Helmer, a history graduate student at the time who would also become a writer, reported on the practical effect of the students' efforts:

I remember thinking, "All we need is a bunch of idiots running around with rifles." But what they did turned out to be brilliant. Once he could no longer lean over the edge and fire, he was much more limited in what he could do. He had to shoot through those drain spouts, or he had to pop up real fast and then dive down again. That's why he did most of his damage in the first twenty minutes.

Ramiro Martinez—one of the three police officers who made their way up the tower with an armed civilian volunteer, engaged Whitman and shot him dead—said of the noise he heard up on that observation deck, "The shooting outside sounded just like rolling thunder."

Whitman's actions drew so much attention that voters might have anticipated changes in gun laws, something people had been agitating for since Oswald's mail order purchase. But those changes didn't come. It was only after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy that the first Texan president was able to sign the Gun Control Act of 1968—or what was left of it after the gun lobby finished its work. The law finally halted mail order gun sales and required licenses for any interstate sales, but in his remarks at the signing ceremony, Lyndon Johnson was more focused on what was not in the new law:

I asked for the national registration of all guns and the licensing of those who carry those guns. For the fact of life is that there are over 160 million guns in this country—more firearms than families. If guns are to be kept out of the hands of the criminal, out of the hands of the insane and out of the hands of the irresponsible, then we just must have licensing. If the criminal with a gun is to be tracked down quickly, then we must have registration in this country. The voices that blocked these safeguards were not the voices of an aroused nation. They were the voices of a powerful lobby, a gun lobby, that has prevailed for the moment.

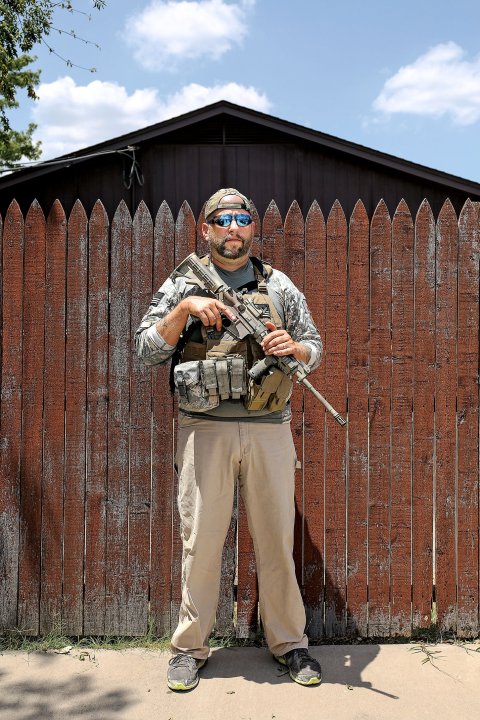

Texans' Habit

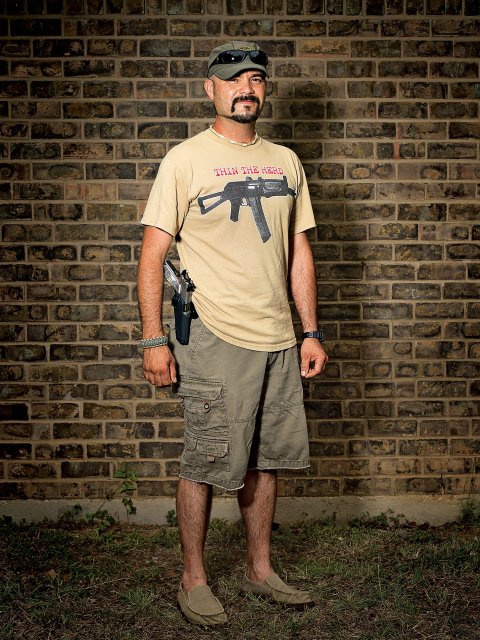

Living in a state where "vaqueros," cowboys, do not stand out in a crowd, and guns are just another dangerous tool that must be handled with care, it's easy to have disdain for those "gun grabbers" who don't know the difference between semi-automatic and full automatic weapons. I don't have bad feelings about those who advocate new gun laws with limited information, but I understand the friction when urbanites are brought to Texas by their jobs and find themselves living next door to somebody who owns enough firepower to turn back the siege of the Alamo singlehandedly.

But I also know that gun nuts are not rushing out to commit crimes. Asking myself why so many people are so determined to enact more legal limits on guns, I spent a few minutes trying to remember any acquaintance who had been killed or seriously hurt by a gun.

There was Neal, who gave me my first job delivering newspapers. Neal accidentally shot himself in the head with the gun he always kept under his pillow. He lived but had major brain damage.

I joined the staff of Austin underground newspaper The Rag right after George Vizard was shot dead in a robbery of the convenience store where he worked. Vizard was the first victim of Robert Joseph Zani, whose trail stretched over 14 years, three states and an unknown number of victims, and whose depredations inspired a true-crime book, The Zani Murders.

A speed freak, who got kicked out of the house full of hippies where I lived because he was stealing, kicked it up a notch within the year and robbed a married couple, shot them both dead and set their car on fire with their bodies in it.

The former editor of The Daily Texan who hired me for my first respectable journalism gig was shot dead while driving a cab in Houston.

A photographer who did piece work for the law firm at which I was employed and who dated one of the partners was shot dead in a home invasion.

The young son of a police sergeant who was a good friend of mine got ahold of his dad's service revolver and killed himself by accident.

Steven Fromholz—one of my favorite guitar pickers and the Texas poet laureate of 2007—shot himself dead on his way out to shoot feral hogs when he dropped a loaded rifle.

A very capable lawyer who practiced in the courthouse where I used to sit as a judge is confined to a wheelchair because of a similar mishap.

Jan Reid, one of many Austin writers who orbit around Texas Monthly and the Texas Observer and The Austin Chronicle, was in Mexico City for a prizefight when he was shot and seriously injured resisting a robbery. His memoir of the event is called The Bullet Meant for Me.

The director of the University YMCA when I was living in Austin pissed off a dope dealer. One night, there was a knock on his door. When he opened it, he was shot dead.

The son of a couple in my circle of friends was kidnapped at gunpoint while using an ATM. After his ATM account was tapped out, they locked him in the trunk of his car and ran it into the Colorado River.

I am reminded every day that I'm old, but that still seems like a long list.

I now live in an age-restricted subdivision north of Austin. Serious crimes counted by the FBI in the five years before I moved in: zero. Since I moved in seven years ago, there have been two burglaries. The most common crime here is bunco—un-needed repairs and bogus get-rich-quick schemes aimed at the elderly. I have two firearms in my house, a pistol and a shotgun. Why? Habit. And because I live in Texas.