‘Robin Hood in reverse’: the crisis in the Brazilian state

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Alvaro Pinheiro is looking for a new life. The 53-year-old recently left a high-powered career that took him round the world with multinationals including Chevron, Procter & Gamble and DuPont.

Now he wants to take things easier, with a less demanding job in Brazil’s public sector that will give him security, decent pay and a generous retirement scheme.

“There was a time in the corporate world when [the stress of work] made me ill,” he says. “In the public sector, you have the chance of an easier pace.” The salary is less than he used to earn but he will get a better pension. “The most tempting thing is the quality of life.”

The former executive is studying for an entrance exam to become an auditor in Brazil’s revenue service. He is far from alone: an estimated 162,000 civil service jobs will be filled by those who pass such exams in 2018. Every year, 12m-15m people take the tests.

Mr Pinheiro’s eagerness to get on the public sector payroll is one small example of the problem at the heart of Brazil’s economic and political troubles: a quasi-dependency on the state that permeates business and society and which has left the government able to do little other than pay its running costs.

Brazilians vote next month in the most hotly contested and controversial poll since direct elections were restored in 1989.

The most popular would-be candidate, former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, is in prison and barred from running, while another, Jair Bolsonaro, was stabbed last week.

In a political environment that has become sharply polarised, opinion polls suggest there is a strong chance that the second-round run-off will be between the far-right Mr Bolsonaro and a candidate from the left.

Whoever wins, however, the next president will face two interlocking crises that will probably define his or her term in office. The first is rising debt and deficits.

The government is running a budget deficit equal to 7 per cent of gross domestic product, even though it is in the throes of an austerity programme.

It means that Brazil risks falling into a new slump if the next administration does not take swift steps to rein in spending. The current travails of Argentina are a reminder of how swiftly markets can turn on countries with policies that start to appear unsustainable.

The second dilemma is the perverse priorities that dominate public spending in Brazil and the way that interest groups, such as civil service unions, have captured large parts of the budget.

The government now has to spend such a large proportion of its revenue on salaries and pensions that it is losing the capacity to invest in areas such as health and infrastructure, or the maintenance of some of its best museums.

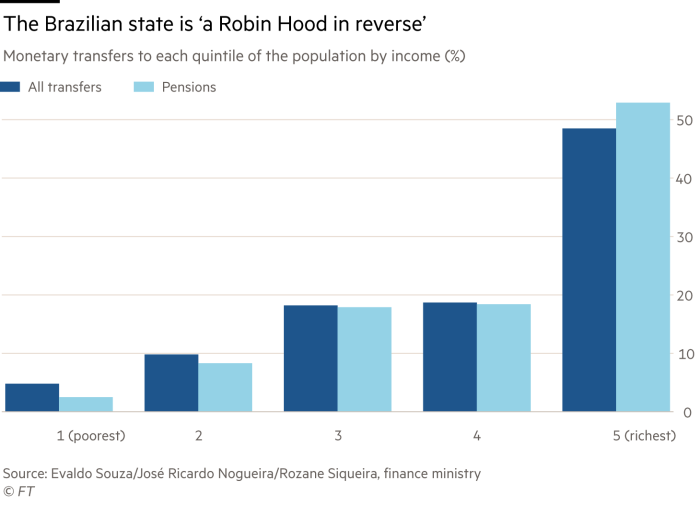

Public spending in Brazil “is completely irrational”, says Rozane Siqueira, a professor of economics at the Federal University of Pernambuco and co-author of a recent finance ministry report on income transfers.

With such a large part of what counts as social spending going to the upper middle class, she describes the government as a form of “Robin Hood in reverse”.

The crisis of the Brazilian state is not a result of insufficient resources. Brazil’s tax take is equal to about 32 per cent of GDP, much more than in many other emerging economies but in line with the OECD developed country average of 34 per cent.

Ms Siqueira says government spending on income transfers, through pensions and other welfare schemes, at 23 per cent of GDP, is also in line with the OECD average.

The outcomes, however, are dramatically different. In the UK, she notes, welfare transfers make up 92 per cent of the incomes of the poorest 10 per cent of the population and 2 per cent of those in the richest 10 per cent. In Brazil, transfers make up just 31 per cent of the incomes of the poorest 10 per cent, and 23 per cent of the richest.

The most glaring example is the state pension system. Ms Siqueira says the government spends more than a third of tax revenue on pensions, of which 53 per cent goes to the wealthiest 20 per cent of the population by income, and just 2.5 per cent to the poorest 20 per cent.

The public sector is particularly iniquitous. In 2017, the average pension for retired judges was R$18,065 (about $4,380) a month: many got three times that amount. Average pensions in the legislative branch were R$26,823 a month. Civil servants often retire — on full pay or more — in their early 50s.

Why are the poor not out in the streets, tearing up cobblestones in protest? “That’s a question I ask myself,” Ms Siqueira says. “It’s shocking.”

The need to reform Brazil’s unaffordable pensions system has been high on the policy agenda for the past quarter of a century.

While insiders often block change in emerging economies, Marcos Lisboa, a former secretary of economic policy in Brasília and now head of the Insper business school in São Paulo, says that what makes Brazil different is the prevalence of vested interests throughout society which are thwarting reforms.

“What people don’t understand is the size and extension of special interest groups in Brazil,” he says.

The public sector pensions system is just one example of the sort of special treatment that insiders have been able to secure over the years. The business sector has done much the same.

Jorge Rachid, head of the federal revenue service, says more than 1,000 proposals were made to his office last year by individuals and organisations seeking tax breaks, in addition to an unknown number of similar proposals pitched to Brazil’s 27 states and more than 5,000 municipalities. “Some of the proposals make no sense at all but we have to evaluate them all,” he says.

While many are rejected, just as many are approved. The share of federal tax revenues given back in tax breaks rose from 15 per cent to more than 22.5 per cent in the decade to 2015. This year it will be 20 per cent, or about R$290bn, according to the revenue service.

The biggest beneficiaries of such tax breaks are small- and medium-sized businesses. Others include the Zona Franca de Manaus, a tax-free manufacturing zone in the middle of the Amazon rainforest, and industrial sectors selected as “national champions”. Big companies perfectly able to borrow on global markets receive taxpayer-subsidised loans from BNDES, the state development bank, at no discernible gain to investment or productivity.

The handouts stretch beyond business. Under one federal programme, some 20m low-income workers in the private sector receive subsidised meals or food vouchers — and more than 23,000 nutritionists are employed to guide employers.

The popular idea that the state should mandate generosity is typified by the meia entrada, an obligation placed on cinemas, football clubs and promoters of cultural and sporting events to offer half-price tickets to students, the elderly and the disabled.

“Everybody always gets something,” says Zeina Latif, economist at XP Investimentos, a São Paulo brokerage. “On balance everybody loses out because the economy grows less than it should, but for some sectors the net outcome is great . . . which is why we have such a strong concentration of wealth.”

Sérgio Lazzarini, an expert on crony capitalism, says businesses are able to demand favours from the government because of the costs imposed by its often unpredictable actions, such as imposing tariff cuts on utilities, that contradict the details of their concession contracts.

“The government intervenes strongly, and businesses say OK, if you want to cut my tariffs, I want a subsidised loan,” he says.

He describes Brazil’s system as one of “relationship capitalism”, in which politics and businesses are intimately linked through the government’s ownership of majority and minority stakes in big companies, be it directly or through the BNDES and public sector pension funds, and the desire of businesses to secure cheap funding, public contracts and other benefits.

The risks entailed have been laid bare by the ongoing Lava Jato investigations into corruption involving politicians and officials at Petrobras, the state-controlled oil company, Odebrecht, the construction and engineering group, and a host of other companies.

Both democratically elected and military governments have indulged these special interests over the years but the pressures on the budget were exacerbated during the 13-year period that the leftwing Workers’ party occupied the presidency from 2003 to 2016.

Mr Lisboa says that in the US and Europe, the difference between left and right is that the left favours equality at the cost of slower growth and the right favours growth at the cost of greater inequality.

“This is not the debate in Brazil,” he says. “In Brazil and Latin America, to be on the left means, first, to be opposed to US imperialism and second, to defend local corporate interests, to close the economy . . . But where is their social policy? Where is their concern for education for the masses?”

1. Costly operations

State pensions

In 2016, Brazil spent R$498.5bn on state pensions for 29m private sector pensioners, delivering average annual payments of R$17,080. For public sector pensioners, it spent R$110.7bn on just under 1m pensioners, delivering average annual payments of R$113,060.

Simples Nacional

Small to medium sized businesses with annual sales of up to R$4.8m benefit from a simplified tax system that rolls a host of corporate, payroll and welfare taxes into one contribution. Next year, the cost of such benefits will be R$87.3bn, according to the finance ministry.

In 2003, as secretary of economic policy in Lula da Silva’s government, Mr Lisboa proposed overhauling Brazil’s welfare system to concentrate its benefits on the poor. “That document was machine-gunned by the left, especially the part about focusing social programmes on the most vulnerable families,” he remembers. “They said no, benefits must be universal — but how?”

Lula da Silva’s supporters say his social programmes and grants for university students directly target the poor.

Until now, many difficult questions have been put off. But that route may have run its course. By official estimates, obligatory spending already consumes more than 90 per cent of the federal budget and, if nothing changes, will reach 120 per cent in the next decade.

2. Costly operations

BNDES

The state-owned National Bank for Economic and Social Development is the only significant source of long-term lending to businesses in Brazil. Its loans typically come at interest rates of about 12 per cent a year, compared with an average rate from commercial banks of 55 per cent. In 2016, the cost to the government of its subsidised lending was approximately R$47.8bn, according to the World Bank.

Zona Franca de Manaus

This manufacturing hub was established near Manaus, deep in the Amazon rainforest, in the 1960s. Critics say it generates no benefit other than the tax breaks given to companies operating there, which next year are set to cost taxpayers R$30.2bn, according to the finance ministry.

Sistema S

A group of non-profit private bodies that provide training and leisure facilities for business and commerce and cultural centres. Its entities are financed primarily by money that is passed directly from company payrolls without going through the national budget and is largely unaudited. The system’s combined income last year was at least R$32bn, according to Brazil’s public accounts tribunal.

Mr Lisboa reckons the true figure is already close to 100 per cent and that the next government will have no choice but to introduce tough reforms. Otherwise, it “will not have the power to decide anything”.

Brazil has so far avoided the turmoil that has savaged neighbouring Argentina for much of this year, where longstanding imbalances and the mis-steps of an otherwise avowedly reformist government have been exposed by the strengthening US dollar and tightening global monetary conditions.

Until recently, markets have taken it for granted that Brazil, too, will have a new government that takes the fiscal problems seriously. They have even warmed to Mr Bolsonaro, ignoring his admiration for Brazil’s military dictatorship and its corporatist policies.

The recent slide in Brazil’s currency suggests that investor confidence has been shaken. If the millions of people who dream of an easy life in civil service will not push for change, markets may do the job for them.

Economic proposals Left v right

A quarter of a century ago, before the wave of crises that hit emerging markets in the late 1990s, Brazil became a model of liberal reform. Its government introduced inflation targeting, a floating currency and a series of laws aimed at bringing public spending under control.

Brazil was soon riding the commodities supercycle to a decade-and-a-half of prosperity. Under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the leftwing Workers’ party, president from 2003-10, many observers thought Brazil had found a “third way” of matching macroeconomic stability with social responsibility.

Yet, that period now feels like a blip. When Dilma Rousseff succeeded Mr Lula da Silva in 2011, it was commonly argued that she had little choice but to address glaring fiscal imbalances. Instead, she increased state intervention, helping to cause the worst recession in Brazilian history, with a 7 per cent contraction in gross domestic product in 2015-16.

Although Fernando Haddad, Mr Lula da Silva’s replacement as presidential candidate, is one of the more moderate members of the Workers’ party, its rhetoric has shifted left and many of its policies echo the approach taken by Ms Rousseff. Ciro Gomes, another leftwing candidate doing well in the polls, has proposed interventionist policies that have also alarmed investors.

Jair Bolsonaro, the current frontrunner in next month’s presidential election, has tried to position himself as a reformer. However, critics say his voting record in more than two decades in Congress shows his statist instincts. Mr Bolsonaro “is a nationalist of the old ilk, of the type that we have seen in Brazil time and time again”, says Monica de Bolle, director of Latin American studies at Johns Hopkins SAIS. Should he make it to the presidency, she predicts, he will be no match for Brazil’s vested interests. “He will end up caving in to everything.”

Comments