Media

Is Political Polarization Natural? What Ants Show Us

Humans and animals share behaviors, including splitting into competing groups.

Posted January 19, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

I first became interested in how biology affects political behavior when I read a book named Cheating Monkeys and Citizen Bees: The Nature of Cooperation in Animals and Humans by biologist Lee Dugatkin. From this and other research, we know that chimpanzees engage in what many of us would recognize as warlike behavior, vampire bats share food, humans and mice with the same genetic alteration demonstrate the same anxiety-related behavior, and humans and non-human animals prefer some of the same characteristics in their leaders.

So, a recent article in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface by Christopher Tokita and Corina Tarnita from Princeton’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology grabbed my attention. The article has one of those technical titles that’s almost indecipherable to non-experts, but it’s basically about how political polarization in humans is attributable to the same forces that certain ant behavior is attributable to.

Polarization in Humans and Ants

Political polarization is one of the hottest topics in the political world these days. The Pew Research Center defines political polarization as “the vast and growing gap [in attitudes and behaviors] between liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats.” Ultimately, a lot of the political system’s ills—across the globe, not just in the US (see, e.g., the UK and Brexit)—are attributed to the gridlock and incivility often associated with political polarization.

Research like Tokita and Tarnita’s on the possibility that human and ant behavior share common motivating forces intrigues me. After all, both humans and ants are highly socially organized and cooperative and must navigate complex environments. (Note: if you want to get into the weeds about similarities between human and ant societies, you can see very interesting and controversial arguments about things like eusociality by E. O. Wilson). The idea that they both experience powerful social divisions tied to the same factors is not surprising to me, but I certainly want to hear more of the details of their argument.

The Details

In their research, Tokita and Tarnita argue that two forces that drive polarization in the ant world—i.e., division of labor—also drive polarization between political conservatives and liberals. The first is social influence, which leads individuals to change their behavior in response to the behavior of the individuals they’re interacting with (thinking about your high school years, think of peer pressure).

The other is interaction bias or homophily, which leads individuals to interact with other individuals that are similar to them (thinking again of high school, think of the cafeteria groups of jocks, band members, or segregated races).

In the ant world (there were lots of ants in my high school cafeteria, but that’s another story), you might have some ants that are more motivated by food and others that are more motivated by safety. With regularity, the hungry ants are more likely to go foraging for food, and, therefore, run into other hungry ants, while the defensive ants are more likely to patrol for invaders and, therefore, run into other defensive ants.

Because of the increased time they spend with other ants doing the same thing, through social influence they become more and more like those already similar ants. And, as they become more like the other ants, through interaction bias they become more likely to spend more time with them. As a result, you end up with separate groups with different interests that spend significant amounts of time only with their group.

Of course, the application to the human world is very easy. You can think, again, of high school if you like. Or you can think of something like social media (or any media for that matter). There’s a great deal of research showing that people seek out and consume media that’s consistent with their interests and views, most likely because encountering information that they may be wrong about an issue makes people uncomfortable. As they consume more like-minded information, through social influence their attitudes and behaviors become more consistent with that information. And because of interaction bias, they want to spend more time with people with attitudes and behaviors similar to theirs, most likely because life is more familiar, certain, supporting, and safe with like-minded people.

And, voilà, you end up with different groups with different attitudes and behaviors.

Evidence from the Media, Social and Otherwise

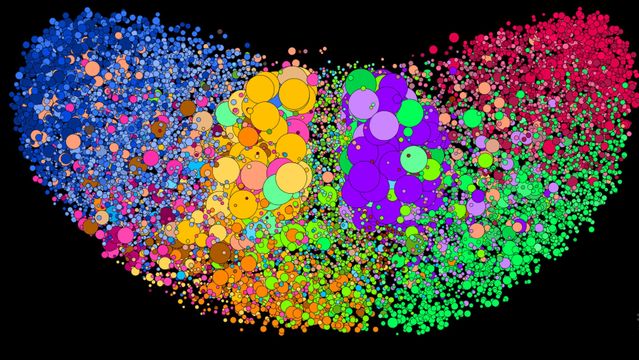

The bean-shaped figure below shows that like-minded groups form on Twitter. Each circle is a Twitter account. Its size indicates the number of followers, while its color indicates the political ideology of the content. The blue circles on the far left are anti-Trump accounts, while the red on the far right are pro-Trump accounts. The two major parties are near the middle, with the large orangish circles indicating the Democratic Party and the large purplish circles indicating the Republican Party.

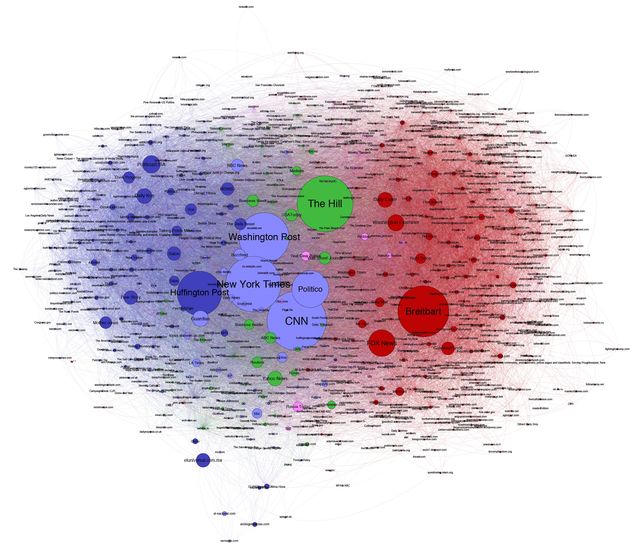

But there’s also evidence of interaction bias all over the human world including at work, where we live, and even in players within worlds created in massive online role-playing games. The next figure, which is based on “co-citations” (i.e., who links to whom), shows that the media world is highly polarized, too.

It's Too Easy

Unfortunately, one of the many problems with political polarization is that it’s apparently very easy to achieve. The suggestive evidence from ant behavior shows it may be a natural process that results from animal behavior, human or non-human, or at least the product of complex social structures. It’s a hot political topic that’s an easy explanation for a lot of problems, but maybe at least it won’t be so “hot” if we understand that we are not polarizing by choice.

References

John Kelly and Camille François. 2018 (August 22). "This is what filter bubbles actually look like." MIT Technology Review at https://www.technologyreview.com/s/611807/this-is-what-filter-bubbles-actually-look-like/.

Christopher K. Tokita and Corina Tarnita. 2020. "Social influence and interaction bias can drive emergent behavioural specialization and modular social networks across systems." Journal of The Royal Society Interface 17. DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2019.0564