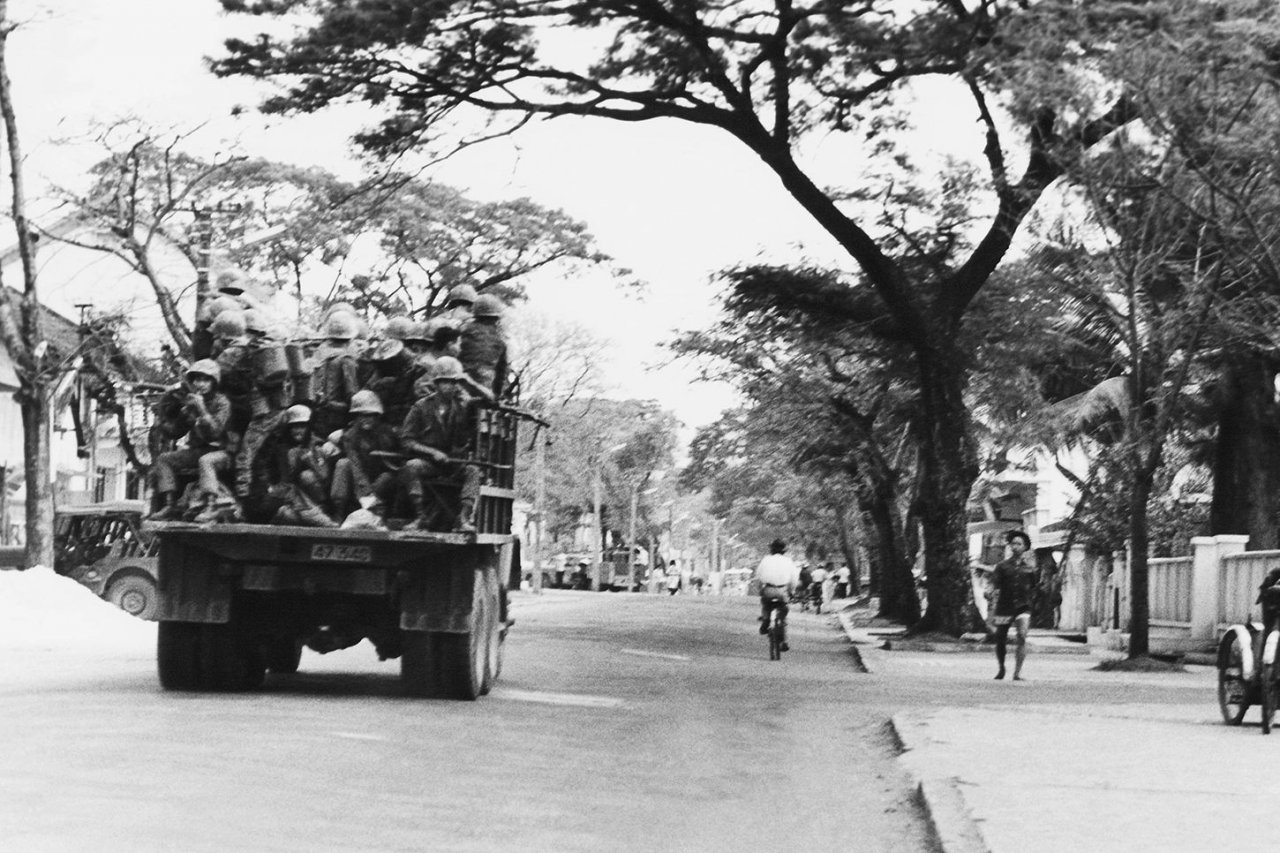

The black Mercedes weaves through the swarms of motorbikes in Danang City, Vietnam. At the wheel is a former Viet Cong guerrilla fighter with a combat ribbon on the lapel of his suit jacket. He takes me along the harbor, once a major port for U.S. Navy ships, then past the site of the former U.S. military command, now occupied by the towering regional headquarters of the Vietnamese Communist Party. Beside him is my minder from the Foreign Ministry in Hanoi, a worldly young man named Duc. I'm in the back seat, next to another former VC fighter, who is regaling me with a tale of ambushing U.S. Marines just north of the city in 1969. Smiling, he raises a trouser leg to show me a bullet wound. I ask him the name of his unit. When he tells me, I nod in recognition.

A half-century ago, I was a U.S. Army intelligence operative here, controlling a network of Vietnamese spies, tracking the movement of enemy forces. I have come back to speak with my former nemesis—the man who ran agents against me, then retired decades later as deputy commander of North Vietnamese military intelligence—Major General Tran Tien Cung.

Just as he had during the war, Cung was proving to be elusive. In their customary fashion, the Vietnamese had frustrated my efforts: Negotiations fell apart again and again. Now, almost 50 years after trying to catch him, I was suddenly getting a chance to meet him face-to-face—to compare notes from our secret side of the war.

As the streets narrow, we pass by the old American air base, once a major staging ground for U.S. Phantom jets taking off for secret bombing raids in Laos. Finally, the driver inches the car into a secluded lane and stops. Serious-looking men appear and open my door, and I step out into the brutal Vietnamese heat. "Wait here," one says. He confers with my man from Hanoi. It's possible, Duc whispers to me, that the general, struggling with the aftereffects of a stroke, will not be able see me after all.

I sag against the car, wipe the sweat from my forehead. Once again, I fear I will miss him, that he will die, taking the secrets of how he eluded the world's most advanced intelligence services to the grave.

'Fucked Up Beyond All Repair'

In December 1968, I arrived in Danang as an intelligence case officer, fresh from a year of intense Vietnamese language study and six months at the Army's school for spies at Fort Holabird in Baltimore. The tradecraft we learned there—servicing dead drops, assessing potential recruits and dodging the Soviet-bloc secret police—was designed more for scenarios out of a John le Carré thriller than recruiting Vietnamese peddlers to track Communist units. But once I arrived in Danang, I quickly learned that one of those key techniques—maintaining my cover—could be far more difficult, and have far higher stakes, than posing as a civilian in Cold War Berlin.

The challenges of real-war espionage became clear on my first night in the city. The occasion was a cocktail reception at the U.S. consulate in Danang, housed in a former French colonial outpost. I was still memorizing my new cover story when I walked in and took a glass from a waiter's tray. As I surveyed the room, a South Vietnamese officer in a white uniform strolled over and struck up a conversation. I was wary: I knew the South's officer corps was riddled with Communist spies. After a few minutes chatting in my newly minted Vietnamese, he asked, "What do you do?"

My heart thumped as I gave him my spiel: "I'm a civilian refugee assistance officer with the Department of Defense." He smiled broadly and took a sip of his champagne. "So you're a spy," he chortled.

On the way back to our high-walled villa in the old French quarter, I poured out my panic to two teammates. "Oh, that's nothing," one said. "The Green Berets captured a VC map six months ago with a big X on our place. It had 'special intelligence house' scrawled on it." Alarmed, I asked why they hadn't moved. They shrugged. "FUBAR," one said—fucked up beyond all repair. "Welcome to Nam." They were headed back to the states as part of the drawdown of U.S. troops. I would be left alone to run an ongoing operation.

I quickly moved to a new house and arranged for a different cover. Soon, I had a steady stream of intelligence reports coming in from my agents. But none could answer my most nagging question: Who's the Communist spy chief running agents against me? We wanted to take him out—to kill him or, better yet, arrange for his capture and interrogation. But I never got a name.

A few days before Thanksgiving in 1969, I left Vietnam and the army. I was done with all that, except for the occasional article on the war's aftermath and a book about Green Berets charged with murder after they executed one of their own spies, a suspected double agent.

Then, one day in early 2012, I got an email that rekindled my interest in my spymaster rival. It came from Merle Pribbenow, a former CIA officer who has spent his retirement years translating documents from Hanoi's archives. Among them: A memoir written by General Tran Tien Cung, identified as the wartime deputy director of North Vietnamese military intelligence. No one else had taken notice of this extraordinary document. Pribbenow shipped me swatches of his English translations. Now, I had not only his name but a location: Cung was chairman of the Danang Veterans Association.

The book, Home and Fellow Soldiers—its anodyne title seemingly chosen to deflect attention—had few cloak-and-dagger details. But one story was shocking, even all these years later: In March 1975, as the Saigon army reeled and retreated in the last weeks of the war, Cung had led an intelligence team into the deserted U.S.–South Vietnamese command center in Danang and captured a huge cache of classified material, including documents identifying enemy agents. "Among the items that we recovered," Cung wrote, "were six cryptographic machines" to make and break codes, plus "a number of machines" that could make foolproof ID cards—advanced gear Hanoi undoubtedly passed along to its allies in Moscow, Beijing and Havana to manufacture counterfeit U.S. identity papers. "We recovered so many documents and so much equipment," Cung added, "the Ministry of Defense had to send down two [Russian] AN-24 cargo aircraft to be able to carry it all back."

That intelligence coup had no doubt helped vault Cung to the rank of general. And when the U.S.-backed Saigon government was defeated, Hanoi gave him a key role in its next great campaign: organizing Cambodian exiles to overthrow the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime next door in Phnom Penh. Vietnam's lightning triumph elevated Cung to the equivalent of the CIA field generals who laid the groundwork for American coups d'états in Iran, the Congo, Guatemala and Panama. But he wasn't through. In 1984, he was put in charge of snuffing out a U.S.-based plot to organize a counter-revolution in Vietnam. He "annihilated" a force of Vietnamese exiles trying to infiltrate the country through Laos, he wrote.

It was a remarkable career for someone who grew up in a "petit bourgeois family" in Goi Noi, a swampy Communist stronghold about 15 miles south of Danang, according to Cung's official biography in Hanoi. He had joined the revolution as a seventh-grader in 1945, and during a short-lived uprising against the U.S.-backed French colonial regime three years later, he was captured and presumed dead, only to escape and fight again. When the revolutionary Viet Minh finally prevailed over the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, and the country was sawed in half at the Geneva peace conference, Hanoi brought him north for intense spy training, at one point shipping him to Moscow for more advanced courses. In 1965, with Viet Cong forces reeling around Danang from the invasion of U.S. Marines, he was sent back down to ramp up Hanoi's espionage efforts. One of Cung's most effective spies was a "major land owner," he recalled in his memoir, who had two gold shops in the Chinese market. Another key agent was "a sympathizer" inside the U.S.–South Vietnamese military headquarters in Danang.

During the Communists' countrywide Tet Offensive in January 1968, Cung's spies managed to obtain "the enemy's military plan" for the area. They did it again when the U. S. organized a major campaign against North Vietnamese units in Laos. That intelligence coup helped turn the assault into a stunning disaster for the U.S. "Certainly, there can be no argument that the Commies cleaned our clock, intel-wise," says Pribbenow, who served five years in the CIA's Saigon station, "although I do believe that a number of their claims in that area are a bit inflated."

All this history was academic to me until I found out that Cung—the man who had put the X on my supposedly secret safe house—was alive and in Danang. In 2013, I began angling for an interview. In the wildest corner of my imagination, I imagined us walking the streets together, visiting our old spy haunts and swapping war stories. After all, American and Viet Cong combat veterans had been revisiting their old battlefields together for years. Why not two old spies?

My first few inquiries to Hanoi got nowhere: The subject was too sensitive, Cung was too busy and then, in 2015, when he was 88-year-old, too ill. I almost gave up.

But suddenly last summer, when I told Vietnamese authorities that I would soon be nearby, in Kuala Lumpur, Hanoi said it might be possible to see him, if I could make it to Vietnam. No guarantees, they said, but we'll see what we can do.

I booked a ticket and headed to Danang.

Dead Drops and Empty Beer Bottles

Like so much that has been forgotten about the U.S. war in Vietnam, the origin of China Beach's nickname seems lost to history. A ribbon of sugary sand stretching for miles south from Danang, it was uninhabited during the war except for the occasional fisherman and the large U.S. Navy base at Monkey Mountain, a crop of steep hills at its northern end. U.S. Navy sailors and Marines would come for a swim and a few beers. Behind them in the quiet palm groves and rice paddies, the sight of young boys on water buffaloes offered an illusion of bucolic seclusion. Many, we knew, were VC lookouts. And from beyond the distant hills came the muffled thumps of outgoing U.S. artillery. In early 1969, I swung by to scout it for a possible dead drop or meeting place.

Decades later, on August 18, 2017, I checked into the Furama, one of the gated luxury resorts that now sit on the beach. Across from the entrance, the rice paddies that once graced the landscape were gone, replaced by a highway lined with bustling restaurants and amusement parks. I checked into my room, unpacked and waited for the call from the people who'd said they'd let me see Cung.

And waited. Through a back channel to Hanoi, I learned that my request had kicked up a bureaucratic battle among party officials and government ministries. The foreign minister was under attack, my informant said, for helping set up interviews with internal critics of Hanoi for the Ken Burns–Lynn Novick PBS TV series on Vietnam, which had displeased officials for its depiction of party purges, war weariness in the North and Communist massacres in the South. Plus, he said, Cung was infirm. He might not live much longer, much less wander the streets with me comparing notes on our secret war.

Another day passed. Then, I got an email from Duc, who had been assigned by Hanoi to accompany me during my visit. (Foreign reporters are not allowed to roam alone in Vietnam.) He said he would be flying down to meet me the next day.

Free for 24 hours, I took off on my own.

Confessions and Cover Stories

First stop was my old safe house at No. 3 Nguyen Thi Giang, once a sleepy street in the old French quarter. The only problem: The address didn't exist anymore. The Communists had stripped the streets of names honoring the imperial past and replaced them with homages to revolutionary heroes. After the hotel concierge slipped me a prewar map, however, I was on my way.

As the taxi ferried me from China Beach across the broad Han River, I hoped I'd find some surviving remnant of the quiet old French Quarter where I'd lived. Back then, a nearby Catholic school, run by French nuns, disgorged a parade of smiling young schoolgirls in their conical hats and flowing white áo dàis.

Behind the high walls of our villa, I'd spent the year hunched over a Royal typewriter, translating and typing up reports from my 13 Vietnamese spies, one of whom was a double agent commanding a Viet Cong rocket squadron. His urgent warnings of an impending attack on the city or nearby U.S. military bases were rarely wrong. "Dao," as I'll call him here, had been recruited out of a U.S. holding center for Viet Cong defectors. He'd expressed such disillusionment with the revolution that he said he'd be willing to go back as our spy, and we took him up on it. Next, we found a peddler who regularly traded with Dao's unit. That gave him cover to banter with the commander, who would whisper his unit's attack plans as they made a sale.

Cung had spoken of such betrayals in his memoir, how "some cadres who were not able to endure the challenges defected to the other side." And I had one of them. Yes, we had that big X on our house, but at least we were in the game. Until the Communists chased us out of Vietnam.

Now, our safe house was gone. The old French quarter had been razed and replaced with a clutter of shops and apartment buildings. Rivers of motorbikes and Korean cars clogged the streets. I took a few pictures, got back into the cab and gave the driver a new destination: the city beach where I'd once had clandestine meetings to pick up reports.

During lunchtimes back then, I'd drive by a soccer stadium looking for a 5-inch scratch on one of its fading ocher walls. Horizontal meant I had reports to pick up, at a prearranged location. Vertical meant trouble, a signal for an emergency meeting.

The most common meeting place was a shaded small beach about a mile away. I'd drive up in my jeep with U.S. diplomatic plates, give a cursory glance around to see if I'd been tailed, then walk down to the sand, unfurl a towel and strip down to take a swim. If I saw nobody suspicious-looking, I'd leave the water and shake out my towel as a "safety signal" to a courier hidden nearby. (Folding it meant abort.) A few minutes later, a young boy would come along selling ice cream from a wooden box slung over his shoulder, and I'd buy a cone. It was wrapped with a thin sheaf of reports scribbled in very tiny handwriting. The tradecraft was as old as God's command to Moses to "send men to spy out the land of Canaan."

Intelligence trainers teach aspiring spies that they can't be too careful with such transactions. Enemy agents can bring down an entire spy network if they uncover a courier (as the CIA did when it was hunting Osama bin Laden). Cung thought their anonymity was so critical that, during a stint in Hanoi at military intelligence headquarters, he chose women for the job—less likely to be stopped by South Vietnamese police—and segregated them from his other spy trainees. "These women were not allowed to tell anyone anything, where they worked or what they did," he recalled in his memoir. "For that reason, nobody knew that, for example, this lady was an intelligence agent, or that that lady was preparing to be sent to South Vietnam."

Despite Cung's precautions, however, my spies, many of them small-time merchants, were regularly uncovering the arrival of Cung's women in the Danang area. A typical report would read that Miss So-and-So "has returned to Hoi An from a six-month absence and is working as an assistant tailor" at a certain shop. "She has told neighbors she was studying art in Saigon," an agent might report, "but since she has shown no aptitude for it, they are sure she has joined the Communists."

Such "raw intelligence" was passed along to the local office of the Phoenix Program, a highly classified CIA operation to "neutralize" Viet Cong agents in the countryside. Years later, Phoenix was exposed as a brutal, haphazard assassination program rife with corruption, but not long after my arrival in Danang, I'd learned an even deeper secret about it from an internal CIA document that came my way: Communist spies had managed to infiltrate that too. It was something I was eager to talk about with Cung. In his memoir, he wrote that in 1969 he had "carried out a number of plans to dispatch agents to penetrate the headquarters of the enemy's 1st Tactical Zone" and associated units.

That would be me. Had he gotten inside American intelligence? Such dark thoughts came back as I searched, prewar map in hand in the back of a taxi, for my old clandestine meeting spot on the beach. I urged my driver on through the narrow streets and alleyways, farther and farther from the tourist track. As we crept forward, peasant women toting straw baskets on their heads, and skinny children kicking soccer balls, stepped aside and stared at me. I got a whiff of charcoal smoke and fish sauce, which reminded me of my nervous travels to agent meetings a half-century ago.

The driver now chuckled nervously at our odd journey, perhaps thinking: What if we encounter a Vietnamese policeman who starts asking difficult questions? What is this American doing so far out of the way? A long-buried habit kicked in: I started dreaming up a cover story. I even glanced at the rearview mirrors of parked motorbikes to see if anyone was following us.

So, this is post-traumatic stress disorder, I laughed to myself. Then, the taxi turned a corner and abruptly stopped. An elevated highway loomed in front of us. Beyond, I could see the beach, now shorn of its graceful palms. A sign warned of an off-limits military installation nearby. There would be no revisiting it today—or ever. My old world had been razed—the safe house, meeting places, the soccer stadium, the rickety hotel where, with sweaty palms, I first met my "principal agent" (the go-between for our spy network). A scheming Vietnamese man twice my age, he had worked for the French before us and chain-smoked his coal-like Gitanes all through my hours of debriefing him. All gone.

Except for Cung.

Slipping Out Through the Bamboo

The next afternoon, Duc called from the airport. He suggested we meet at a restaurant along the commercial strip not far from my hotel. A few hours later, we took a table under the bright fluorescent lights of its open-air patio, a place far off the tourist track. Surrounded by Vietnamese families, we ate and drank long into the night. Urbane and sophisticated, he probed me on my war experience and views. And I asked about his. As the empty beer bottles crowded the table, I learned he was connected to the highest levels of Hanoi's national security elite. His father had been an ambassador. An uncle was high up in the Internal Security Ministry. He had studied in China and done a stint at Hanoi's consulate in San Francisco.

I enjoyed his company, and he mine, I think, especially when we talked about the meaning of Vietnam's epic national poem, The Tale of Kieu, the 18th-century story of a beautiful young girl who sells herself into prostitution to save her family.

But I knew he was sizing me up. And that I was running out of time.

The next afternoon, the opening finally came.

"It is a long shot," Duc said, "but meet me at the Danang Veterans Association Office." Thirty minutes later, I was knocking on its second-story glass door on a quiet side street. A dour man behind a big desk at the far end of the room looked up, then stood slowly, clearly surprised to see a Western visitor at his out-of-the-way office. After a momentary hesitation, he walked over and half-opened the door. A military decoration hung from his jacket pocket told me I was face-to-face with a former enemy.

"I am an American journalist," I offered in my rusty Vietnamese. "Tôi là báo chí Mỹ." I tried on a respectful smile. He assessed me without words. "Được," he finally mumbled—all right, it meant, but not exactly OK. He invited me in, motioned me to sit and picked up his desk phone. I began trying to explain that an official from the Foreign Ministry in Hanoi was supposed to meet me there. He raised an eyebrow at that, spoke a few words into the phone and then slowly replaced the receiver. More silence. A few minutes later, two elderly men entered the room, followed by a third. From the looks of the ribbons on their chests, they were all former VC fighters from Danang. They had certainly shot at Americans during the war, I figured, dug booby traps and planted mines, maybe killed some GIs and Marines. And they, too, had suffered immense losses in the war—comrades and family obliterated by American attacks. They did not look pleased to see me. Why should they be?

Finally, Duc burst in, apologizing. With a deep deference to these elders of the revolution, he introduced me in the kindest light. He told them I had written about the lingering effects of Agent Orange, the defoliant afflicting yet another generation of Vietnamese—a major concern for these veterans—as well as the continuing casualties from wartime U.S. ordnance exploding in rice fields. They nodded. I responded with an expression of my sincere interest in reconciliation between both sides, and in my particular case, a meeting with General Cung. They began to soften. Two of the men got up and began to confer privately. One left and then came back with someone else: Cung's son. They whispered, and then Duc turned to me with a big smile: We were going to see the general. The long and winding path that had brought me here was suddenly a short, straight line.

Twenty minutes later, we were driving into the alley behind his house. When I stepped out of the Mercedes and peered at the rear of an unremarkable, two-story cement home, pastel green, I thought, Of course: This spymaster would not live in a place that called attention to himself.

As I waited, Cung's son disappeared into the house. When he emerged a few minutes later, he conferred with Duc. "He is very sick" Duc explained. "You will have only a few minutes." When we were finally summoned by an aide, we passed through the back patio into a spacious, high-ceilinged room. Cung was lying on a tan rattan cot, thin and frail. His aide propped him up and served him a few pills. I glanced at the framed and signed photographs on his wall: Cung with the legendary General Vo Nguyen Giap, the hero of Dien Bien Phu, Cung with Ho Chi Minh. The old man waved me to his bedside. Duc explained my presence. Cung nodded with a weak smile.

In a raspy voice, he said he appreciated how far I had come to see him. He was happy to meet an American. But he had to apologize: He couldn't remember much. The stroke had damaged his brain. But go ahead and ask me a question, he said in Vietnamese. Duc nodded and whispered to me, "He maybe has only time for one."

My mind raced. I had a long list: Had he ever managed to recruit anti-war Americans? How did he get spies inside U.S. bases? (We knew that scores of Vietnamese workers on U.S. bases were giving coordinates to VC artillery gunners.) I wanted to know more about the advanced spy training he had gotten in Moscow, the specifics of the Soviet-supplied "revolution in our intelligence activities" in 1969 that he described in his memoir. And so much more.

As I pondered my question, the general waved a fly from his brow. A fan turned slowly overhead. I told him I had great respect for someone who had managed to dodge the French colonial gendarmes, the Saigon police and then the Americans, from 1945 until 1975 and lived to tell about it.

He weakly smiled and nodded.

"What was your greatest espionage triumph against us?" I finally asked.

He lay in silence, his eyes sweeping the ceiling. His memory was weak, he apologized again. "Lâu lắm rồi," he said—So long ago. But he remembered one encounter with the Americans. It was in the mid-1960s, when he was operating out of his home region of Go Noi, about 15 miles south of Danang. Still flat on his back, he swiveled his head toward me and started rasping out the story in his paper-thin voice, speaking with the accents of the Central Vietnam dialect.

"One day, about a dozen American helicopters landed abruptly" near a house where he was meeting with agents. "Because it was so unexpected, my team did not have enough time to withdraw, so we ran down to the tunnel beneath the house."

Duc waved for him to pause so he could translate. "Don't stop him," I said, "I'm getting the gist." I turned on my recorder.

"The house owner was a woman," Cung said. "Right after she took us down the tunnel, two American soldiers and an interpreter entered the house." But Cung and his teammate suddenly realized in horror that "the radio in the house was still playing" a Radio Hanoi broadcast. If the American's Vietnamese interpreter heard it, he wasn't saying anything. "Where are the Viet Cong?" the Americans demanded. From beneath the floor, Cung overheard the woman saying, "They slipped out through the bamboo when you landed."

Cung said the Americans threatened to burn the woman with lit cigarettes. "We were very frightened in that tunnel. We were afraid that she would say something about us." But she didn't. The GIs apparently ran out of patience and ran off to "chase the Viet Congs."

Not much of a spy story, I thought. Except for this: "The local people were very protective of people like me and our activities," Cung told me. It was clearly a warm memory. "After the Americans left, she invited us up for some sticky rice."

I recalled my encounter at the American consulate, when I was stripped of my cover in an instant, and the initial fear I felt when I learned the VC had put a big X on my team's house. Strangers in a strange land, we always had a mark on our backs. Who were we kidding?

And as Cung wrapped up his story, another one bubbled up in my mind, one that I'd carried in horror for a half a century. One night early in my tour, I'd delivered late-breaking intelligence to the 1st Marine Division headquarters on a hill outside Danang. On the way out, I stopped at a shack that served as an officers' club, pulled up a seat at the rickety bar and asked for a beer. The guy next to me turned out to be a Navy doctor working with the Marines' "hearts and minds" program in the hamlets. "How's it going?" I asked. He stared into his glass. Finally, he turned to me and said, "It's a fucking waste."

I waited for more. After a deep, brooding silence, the doctor told me how he spent his days in rural hamlets handing out medicine and giving shots while a Marine "civic action" unit distributed food, drilled wells and so on. "And then those guys," the doctor said, tearing up and nodding toward the distant thump of outgoing artillery, "blow them away." This was the first I'd heard of free-fire zones, where the gunners had license to loft shells into zones merely suspected of harboring VC guerrillas. The revelation threw me into a week of deep depression. Was I contributing to that? Prodded by my team chief, I finally got back to my spy work, rationalizing that the intelligence I delivered to the Marines was saving American lives. And by 1969, that was pretty much all it was about—saving our own hides. Protecting the lives of ordinary Vietnamese was no longer a primary factor in the U.S. exit strategy for the war. The delusional idea of "winning hearts and minds" that greased our way into Vietnam years before had been eclipsed by a new slogan making the rounds: "When you got 'em by the balls, their hearts and minds will follow." Now, the idea was to shoot, bomb, shell and burn our way out. "Kill anything that moves" was the new order of the day.

And of course, that's why two generations of peasants had given sticky rice and protection to people like Cung and stiffed and lied to people like us. As I listened to the one story he could remember from all his years as a spy, the exhilaration I'd felt from tracking him down melted into a deep sadness. The general seemed to sense it, but he was fading, and it was time to leave. "I'm happy you survived," I said, packing my bag. I offered him my hand. He took it in his brittle grasp and managed a smile. "You also," he said.

Our war was finally over.