The Dark Secrets Lurking Inside Your Outdoor Gear

Allegations of abuse have surfaced at a Bangladeshi factory whose multinational owner manufactures for some of the most popular outdoor brands we love. Here's why that should surprise no one.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Reports of unfair labor practices in the apparel industry seem to come with depressing regularity, and most recently, they’ve involved some prominent outdoor gear brands. In late June, a nonprofit called Transparentem released a report alleging abuse, including physical force and forced labor, at Malaysian factories that supply brands like Nike and Under Armour. Then, in mid-October, an investigation by The Guardian revealed that workers at one of Lululemon’s suppliers—a factory in Chittagong, Bangladesh—were subject to verbal abuse and physically assaulted for breaking rules.

The factory in question was Karnaphuli Shoes Industries, also known as KSI Youngone, a 257,807-square-foot facility where more than 12,000 people produce outdoor clothing and shoes. It’s owned by Youngone, a South Korea–based multinational apparel and footwear manufacturer that operates factories in five countries, including more than a dozen factories in Bangladesh. (We’ll hereby refer to the factory as KSI and the Korean multinational as Youngone.) Youngone is a major manufacturer in Bangladesh, where garment production accounts for more than 80 percent of the country’s exports by value.

The Guardian report focused only on labor practices in the KSI unit that produces Lululemon products. But the company also works with a who’s who of outdoor brands: VF Corporation, parent to brands including Icebreaker, the North Face, and Smartwool, manufactures at KSI; Outdoor Research has been majority-owned by Youngone since 2014 (though the company wouldn’t confirm whether it manufactures at KSI); Patagonia sources products from a Youngone factory in Chittagong (not KSI) and Youngone factories in other countries; and REI works with Youngone factories in El Salvador and Vietnam.

Most of these companies are considered industry leaders in environment- and worker-friendly practices. All, except Outdoor Research, are members of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC), a nonprofit cofounded in 2010 by Patagonia and Walmart to track fair-labor issues in the apparel industry. (Youngone, as a manufacturer, is an SAC member.) Patagonia has an in-house factory-audit program and participates in a number of fair-labor programs. Lululemon audits factories at least every 18 months. VF Corp has approximately 25 staffers who monitor labor practices at all of its tier 1 suppliers (the factories that make finished goods) and 40 employees who work on a sustainable-operations team that focuses on workers’ rights and social and environmental conditions in the local communities surrounding its factories.

This all raises a vexing question: If unfair labor practices are happening in—or close to—the supply chains of brands that are trying to do things right, is there any hope for the industry at large?

The report by The Guardian alleged that KSI factory workers were subject to verbal abuse by managers, including being called “whores” and “sluts.” Workers also said they were hit and slapped, in particular if they broke any rules or left earlier than managers expected. Some claimed they’d been forced to work when sick.

In response to a list of questions, Youngone offered a statement expressing that it takes the situation seriously and is internally investigating the alleged abuse. Lululemon declined an interview request but issued a similar statement, expressing that its investigation was being led by an independent third party. Lululemon initially clarified that its production at the Youngone factory is extremely limited and that the brand “will ensure workers are protected from any form of abuse and are treated fairly.” Nearly two months later, it sent Outside a more detailed statement saying that its investigation “identified findings in line with those that were brought to our attention”—in other words, it confirmed at least some of The Guardian’s allegations. Outdoor Research declined an interview request but offered a statement in response to a list of questions, saying that it is “in direct communication with Youngone on this issue.” In an interview with Outside, VF Corp said it is also pursuing an independent investigation.

In its statement to Outside, Youngone said that its code of conduct requires “a safe, fair, and just working environment” with a “zero-tolerance policy for any form of abuse.” The company also said that its Bangladesh production facilities receive audits on a regular basis from both external parties and internal teams. In the meantime, while it continues evaluating the findings from its internal review, it has initiated “a re-evaluation of the effectiveness of our existing internal systems, including tools such as worker-rights trainings, the framework of multiple communication channels, and a grievance mechanism with a no-retaliation policy.”

Because Patagonia doesn’t manufacture at KSI, it’s not directly investigating the factory, but a Patagonia spokesperson said the company is monitoring the situation. Cara Chacon, its vice president of social and environmental responsibility, added that she was surprised to see The Guardian report about KSI: “[Youngone is] very aware and very diligent in how they treat workers and their corporate social-responsibility program,” she said. However, Chacon’s surprise has been tempered by her long experience with the industry’s convoluted supply chains. “Even Patagonia is not a perfect business,” she conceded. “And issues arise even in the best companies.” There’s an unsettling dissonance between these statements and the types of allegations that were brought against KSI. How can the two realities—companies pledging social responsibility while factory laborers are insulted, assaulted, and forced to work—coexist? The answer mirrors the apparel industry itself: complex, globalized, and layered with nuance.

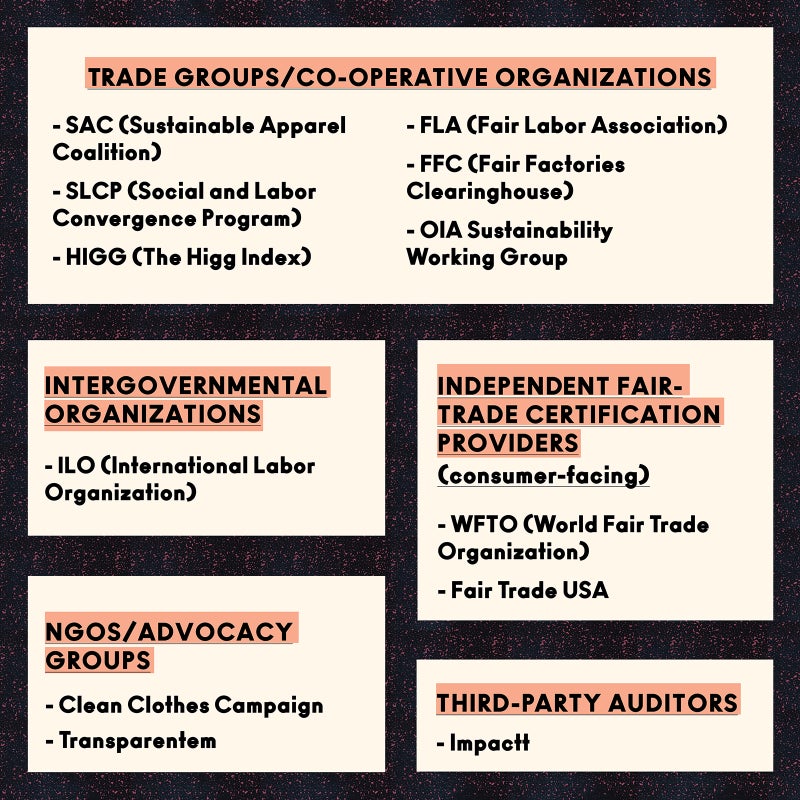

The core of it all is that even expensive technical outdoor apparel is primarily produced by low-paid labor in developing countries, and there’s no single global oversight for fair labor. The basic outlines are set out by the UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO) and are pretty simple: pay living wages, don’t use child or forced labor, provide safe and respectful working environments, etcetera. But the ILO isn’t an enforcement body, and there’s no centralized certification authority for ethical practices—in fact, there are many. Implementation of those standards varies by country, and companies are largely on their own to decide how to monitor fair labor and to what degree.

Another compounding problem is the supply chains themselves, which are fantastically complex. Patagonia alone has products made in 74 factories in 13 countries, and that’s only tier 1 facilities, which make finished goods. Lululemon has 63 tier 1 partners in 16 countries. VF Corp brands work with more than 700 tier 1 factories in 44 countries, and Peter Higgins, the company’s vice president of global responsible sourcing, estimated that its full supply chain may involve more than one million people. Most brands that monitor labor have historically stopped at tier 1 partners; they don’t check labor practices at tier 2, 3, and 4 suppliers—the factories and farms that produce everything from zippers and fabrics to fibers, dyes, and chemicals. (Patagonia claims to be among the few companies that monitors tier 2 and some tier 3 suppliers.) This is slowly starting to change as brands are looking deeper into their supply chains.

Smaller companies often lack the resources to monitor workplace conditions at all, or to push suppliers to change established practices. “Brands don’t own the factories, and there’s only so much influence they have,” Patagonia’s Chacon said. “And if you don’t have a large order in that factory, then you have even less leverage.”

Moreover, VF Corp’s Higgins said that it’s not as simple as cutting ties with a factory over a violation. That might actually make things worse for the workers, he said, because the supplier could sign on with a brand that isn’t committed to fair labor or could simply close the factory and fire its employees. “Our first decision is to stay and remediate to improve working conditions for workers in that factory,” he said. “If we see the supplier is not making progress and not willing to cooperate with investigations, we can exit, but we have to look at the potential negative effects on workers.”

Because of all this, companies often tread warily in certain countries with spotty records on workers’ rights. Youngone is the only tier 1 supplier Patagonia works with in Bangladesh, a country that has some of the lowest worker pay rates in the garment industry. A Patagonia spokesperson told Outside that the company audited the factory for two years before placing its first order. Patagonia does not manufacture in Myanmar, which the ILO has flagged repeatedly for violations like forced work. (Prana, based in California, also refuses to work in Myanmar for the same reasons.)

Third-party oversight groups are one tool that companies use to vet factories. Patagonia and Prana, for example, use the independent organization Fair Trade USA, which certifies factories that comply with the group’s standards on health and safety, working hours and wages, and freedom to organize unions. Both brands are also members of the Fair Labor Association (FLA); like the SAC, it’s an alliance of brands, retailers, suppliers, and other groups that creates voluntary labor standards, with the key distinction that the FLA publishes workplace-monitoring reports about factories’ compliance with those standards.

Even so, keeping track of worker treatment across an entire complex, often multinational supply chain is extremely difficult. At Prana, “environmental sustainability has one standard,” said Rachel Lincoln, the brand’s director of sustainability. “It’s clear that organic is better than conventional [material], that recycled is less impactful than nonrecycled. When it comes to people, there’s not one standard.”

And in terms of what consumers can look for, Patagonia’s Chacon explained that there are at least ten different certifications from groups like the World Fair Trade Organization and Fair Trade USA. Each employs overlapping standards, with differences that can be difficult for the layperson to understand. “There is a lot of [consumer] confusion,” she said.

There are even subtle differences between certifications from the same organization. A Fair Trade–certified seal from Fair Trade USA, for instance, means a cotton garment was created using humane practices from materials to construction. Meanwhile, the organization’s Fair Trade–certified factory designation just means that the factory making the finished garment treats its workers humanely—it doesn’t cover the materials. Meanwhile, there’s the ILO’s Better Work program, which has been effective in raising pay and reducing forced overtime at some participating factories. But Better Work, like the SAC, is purely an industry-facing program, so consumers don’t see a hangtag logo or other obvious mark of participation, and it only operates in eight countries (albeit affecting nearly 2.5 million workers, including those at Patagonia suppliers in Vietnam).

“The challenge here isn’t a shortage of third-party certifications, even in the social space,” said Matthew Thurston, REI’s director of sustainability. “It’s that there’s a plethora of them.”

Some brands stop short of working with certified factories instead setting their own internal codes of conduct. “But there’s a huge amount of ground” between setting a code of conduct and actually translating that code into everyday fair-labor practices, said Thurston. “A whole lot of sausage has been made in that space over the last couple of decades at the industry level.”

The primary method for ensuring fair labor has long been in-person auditing. Brand inspectors or a third-party contractor visit the factory to observe production and talk to workers about things like pay and working conditions. Auditing is expensive, so only big brands like Columbia (which owns Prana), Lululemon, Patagonia, and VF Corp have internal programs. A host of third-party auditing companies exist to tackle the task, but they’re not always reliable. A recent Washington Post story found that third-party auditors in the cacao industry were susceptible to bribes and threats. And a report early last year from the Clean Clothes Campaign pointed out that Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza garment factory, which collapsed in 2013, killing 1,134 workers, had passed numerous third-party checks.

Chacon, a former auditor herself, contends that most inspectors are ethical and committed. “If you’re trained right, you can tell if a worker is being coached or is fearful,” she said. It’s exacting work. The auditor has to select the right interviewees to get a representative sample. They may conduct interviews off factory grounds, where supervisors can’t influence responses, or check shift changes against time-clock data to ensure that workers aren’t being forced into unpaid overtime.

Since countries have widely different laws and regulatory standards, brands can judge for themselves when a practice may be ethically questionable, based on guidelines from the ILO or membership organizations, even while those practices may be legal in a given country. Within country borders, laws may also vary, thanks to free-trade zones—special economic districts that a government can exempt from taxes, labor requirements, and other laws.

For example, in Bangladesh, Youngone operates in three export-processing zones (EPZ), a class of free-trade zone that is eligible for immunity from a broad array of laws, ostensibly to spur economic growth; among those is the 2006 Labour Act, which mandates a maximum hourly workday and week and gives workers the right to unionize. Most EPZs in Bangladesh are government run. KSI, however, exists in a private EPZ that’s owned and operated by Youngone, with the same potential government exemptions as publicly owned EPZs. (The Bangladeshi government deeded the company the 2,500 acres in 1999.)

New legislation in Bangladesh has somewhat improved opportunities for workers to organize unions within EPZs, but the EPZs still have significant restrictions compared to the rest of the country. At least 20 percent of workers have to support forming a union, and illegal strikes can bring fines and even imprisonment (and police commonly disperse protesters, sometimes with force).

As in many countries, worker unrest happens regularly in Bangladesh, and it can be violent. One particularly ill-fated strike in an EPZ occurred in December 2010, when workers protesting that factories weren’t implementing a recent government-mandated wage increase clashed with police inside the Chittagong EPZ, where Youngone operates nine factories. Dozens of workers were injured, and three people were shot and killed. In January 2014, a similar incident at KSI, spurred by a compensation dispute, led police to respond with tear gas and live ammunition, according to news reports. At least a dozen workers were injured and one KSI employee, Parvin Akter, was fatally shot.

Youngone said in a written response to questions about the two protests that “there were many false and speculative media reports on these incidents.” (Multiple outlets, most of them Bangladeshi, independently reported on both protests.) Youngone does not deny that the outbursts happened. But it claimed that Akter’s death resulted “when the police responded to an incident caused by outside miscreants who had broken into the factory” and that the 2010 incident was started by a false rumor spread to incite trouble. The company said none of its workers were among the three dead in the 2010 protests, although two members of its management staff were among the injured. It also said it has improved internal processes for communicating changes in legal benefits to workers.

Faced with this complex, ever evolving set of challenges, the apparel industry is attempting to simplify things. An array of organizations are trying to vet factories and create centralized reporting on their working conditions. The Fair Factories Clearinghouse (FFC) is a nonprofit that allows brands to share information from factory visits. The SAC’s Social and Labor Convergence Program (SLCP) also offers an information-sharing platform and aims to streamline factory assessments and promote more cooperation among brands. And the Fair Labor Association’s workplace-monitoring reports are published on its website.

To consumers, this can all feel disorienting, an alphabet soup of important-sounding coalitions with worthy missions. Progress can seem hard to measure or at least to convey succinctly. And all the while, abuses continue. Membership in trade organizations is voluntary, which means there is often no legal body to levy consequences. “We are not a standards or compliance enforcement agency,” said Amina Razvi, executive director of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, in a written response to questions, “although we do encourage transparency.” Members, who pay an annual dues, have to use the SAC’s tools to work toward improvement. Razvi told Outside that the SAC has a “framework” for reviewing members’ progress but did not expand on what that framework entails or whether the SAC has a formal mechanism to deal with violations or expel members. Similarly, the SLCP allows any organization to join via a small onetime fee, the only mandate being a commitment to publicly support the program’s objectives. “The reality is there are gaps [in the current system],” said REI’s Thurston.

Multiple sources for this article seemed to agree on one thing: no single company is big enough to end unfair labor practices in the outdoor-apparel supply chain. Even the entire apparel industry can’t ensure fair labor, unless companies make human rights a core component of their everyday decision-making. While Walmart cofounded the SAC along with Patagonia, and global brands like Adidas and Nike are members of the FLA, apparel-industry commitment to fair labor is far from universal. “The biggest issue in the apparel industry is that brands don’t support their corporate social-responsibility teams with responsible purchasing practices,” said Patagonia’s Chacon. Moving toward ethical practices by switching to Fair Trade–certified factories, doing the auditing work necessary to ensure compliance, or implementing internal company guidelines can be time-consuming and expensive, and some brands simply haven’t taken that step. “Their commercial goal to increase sales is not in line with their social-environmental goals. They are just completely different paths that never cross,” she said.

So what’s a concerned consumer to do?

First, look for brands that commit publicly and transparently to fair labor, especially those with long-standing involvement. Both the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act and the UK’s Modern Slavery Act require that companies of a certain size doing business in these jurisdictions publicly disclose their efforts to address slavery and human trafficking in their supply chains (even if that’s nothing at all, in the case of the California law). Those statements—which companies are required to publish on their websites, although you might have to dig—are an important clue about a company’s sincerity.

Some companies also share their tier 1 supplier lists and even the results of their internal supply-chain audits. For example: Patagonia’s Migrant Worker Standard, established in 2015, wasn’t spurred by a journalistic exposé or law-enforcement action but by an internal investigation that found labor brokers were charging some migrant workers in Taiwan exorbitant fees—sometimes as much as $7,000—for factory jobs. In 2015, Patagonia voluntarily disclosed the problem on its own website while announcing a new standard it created in response.

Second, consumers can put pressure on companies to stand up against worker abuse. Prana’s Lincoln said that the company has seen a huge shift toward interest around fair labor, especially since the Rana Plaza disaster. “There’s more awareness that this is something we need to focus on and we can actually change,” she said. But consumers’ memory of the news and their capacity for outrage fades over time, pushed aside by thoughts of the next powder day and the new gear they need to enjoy it. “There’s a portion of the membership that cares very passionately about these topics and is keen to have the co-op engage in this space,” but it’s a minority, said REI’s Thurston. “I’d like to believe everybody cares about this at some level. Oftentimes they just don’t know where to start with the right questions.”

In the course of reporting this story, Outside made inquiries to Lululemon, VF Corp, and Youngone about the status of their respective investigations into KSI. As of press time, VF Corp and Youngone had declined to share their results.

Lululemon did share a statement, which it also published on its website in late December. For its investigation, the company enlisted Impactt, an “ethical trade consultancy,” and conducted more than 650 worker interviews. Lululemon said it worked with Youngone to take immediate action at KSI, like removing supervisors responsible for the abuses. Lululemon and Impactt are also setting up an independent hotline for workers to confidentially report issues (separate from Youngone’s existing grievance-reporting system) and are updating training and education to reflect a zero-tolerance policy for any workplace abuses. Lululemon said it currently has no product orders with KSI “and will evaluate future business when the actions are successfully completed.”

That statement is a good start, but Outside only got it after months investigating this story. If consumers don’t demand that information, they’ll likely never get it, which again leaves the companies to be their own fair-labor police.

Ultimately, real, lasting change will cost money and time, both for brands and consumers. More companies need to think hard about whether the drive to increase sales and profits is coming at a social cost that’s too high. And outdoor enthusiasts should remember that social responsibility involves more than a hangtag telling us our gear is environmentally friendly.

We’re not talking about $20 fast-fashion sweaters. We’re talking about $100 leggings, $200 hiking boots, and $400 ski jackets. We pay high prices for outdoor gear because we’ve decided that quality products that keep us happy and safe—and that minimize their footprint on our natural playgrounds—are worth the cost. Maybe it’s worth a little more to ensure that the people who make our gear are taken care of, too.