(The following is an excerpt from The Untold Vajpayee by Ullekh N.P. published by Penguin Random House)

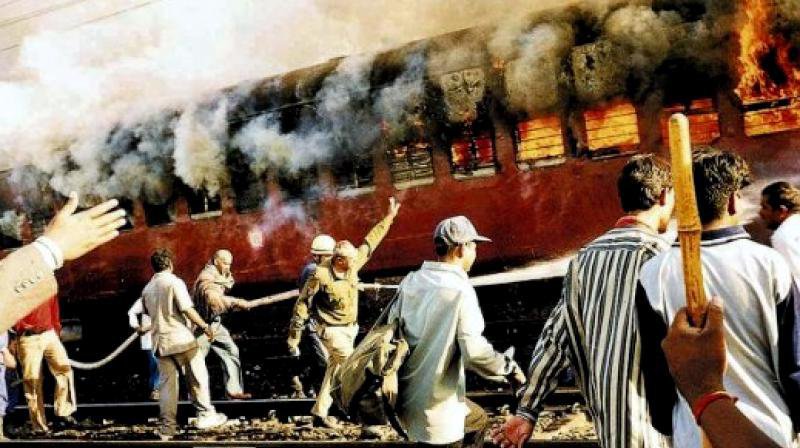

Shourie found the PM deeply disturbed, not looking up, his face grave. He appeared crestfallen. Soon, Shourie realized that the PM was upset for one major reason: Gujarat. On 27 February 2002, a group of people from a Muslim populated area of Godhra had set fire to a few bogies of a train—the Sabarmati Express—which carried pilgrims from Ayodhya, a town considered holy by the Hindus.

Massive riots broke out, mostly targeting Muslims, for nearly a week. All the killing and pillaging in Gujarat had given Vajpayee a bad name, the more so because Gujarat had a BJP government in place, with a chief minister who had reportedly not risen enough to the occasion to rein in the violence.

Vajpayee was blamed for his failure as PM to get rid of Chief Minister Narendra Modi, who reportedly shouted back at a Muslim leader on the phone for seeking help after a mob had gathered outside his house. Some hours later, the Muslim leader was lynched, and Modi is alleged to have asked the police forces to let the violence continue.

At that moment, Modi seemed to be the villain who brought a lot of shame to the central government. Modi had also dared to publicly snub Vajpayee at a press conference where he was seated alongside the prime minister. The reporter wanted to know Vajpayee’s message for the chief minister in the wake of the riots.

In controlled displeasure, Vajpayee stated that Modi should ‘follow his Rajdharma’. He explained that Rajdharma was a meaningful term, and for somebody in a position of power, it meant not discriminating among the higher and lower classes of society or people of any religion.

In a bid to stop Vajpayee from saying something scathing about him, Modi turned towards Vajpayee, tried to catch his eye and said with a strong note of threatening defiance, ‘Hum bhi wahi kar rahe hain, sahib (That is what we are also doing, sir).’ Vajpayee immediately changed tack and said, ‘I am sure Narendrabhai is also doing the same.’

Three days before his foreign tour in April, when Vajpayee visited the Shah Alam camp in Ahmedabad, which housed 9000 Muslims displaced by the riots, he was deeply touched when a woman told him that he alone could save them from the hell that their lives had become.

Now, on the flight to Singapore, Vajpayee was worried he would expose himself to more humiliation while outside the country. His grouse was: why am I being paraded abroad at such a time? Shourie suggested that the PM speak to Advani, who had by now become the deputy prime minister, about the possibilities of salvaging the situation—it could even mean replacing Modi. But even after the ‘pep talk’ with Shourie, Vajpayee appeared cheerless.

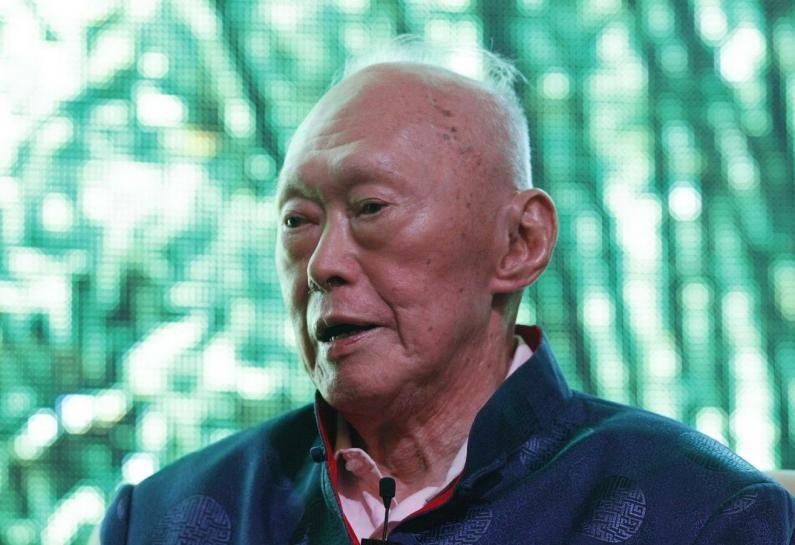

He told Shourie that he would speak to Advani about it. They reached Singapore; there were no meetings scheduled for the first day. The next day there were several engagements, including ceremonial visits to dignitaries, which included the former ruler Lee Kuan Yew. The Gujarat issue came up in an interview on the third and final day of their stay in Singapore.

The journalist who interviewed Vajpayee first stated that Singaporeans were wary of communal disturbances, clearly indicating that he was referring to the recent riots in Gujarat, under the BJP rule. Then he shot off his question: ‘And in India such disturbances have happened not once, but several times. In this regard what can Singapore learn from India’s experience and what can you share?’

Vajpayee paused and rubbed his forehead with his right hand before answering, betraying a level of discomfiture in answering questions related to the Gujarat riots. Then, weighing his words to make it as official as it could get, he said, ‘Whatever happened in India was very unfortunate. The riots have been brought under control. If at the Godhra station, the passengers of the Sabarmati Express had not been burnt alive, then perhaps the Gujarat tragedy could have been averted. It is clear there was some conspiracy behind this incident. It is also a matter of concern that there was no prior intelligence available on this conspiracy. Alertness is essential in a democracy. We have been cautious. And if one does not ignore even small incidents like one used to in the past, then one will certainly be successful in fighting terrorism.’

Clearly, he was on the defensive, and the issue worried him no end. Sensing the Indian prime minister’s apparent unease, the interviewer shifted to Vajpayee’s poetic skills. The interviewer reminded him of a statement he had made after the Agra Summit—that he would now write poems again. ‘Do you have any such plan . . . now?’ Vajpayee replied, recovering a little, ‘No, the result of Agra was not good. I did not get any inspiration from that to pen any poem.’

political infighting, it was decided that Modi would replace Keshubhai Patel as chief minister of Gujarat. On 1 October, Vajpayee asked Modi to meet him in Delhi, where Modi had lived for the previous three years. Modi had put on weight from the last time they had met. Vajpayee joked about too much ‘Punjabi food’ and then got to business.

Modi had to go to Gujarat as CM to prepare the state for the next elections due in 2002, Vajpayee said. Modi’s immediate answer was a ‘no’. Vajpayee insisted, because the Keshubhai Patel administration had incurred public wrath over not doing enough for the people of the state after the 2001 earthquake.

Some members of the government were in cahoots with unscrupulous builders indulging in shoddy construction. Some of them enjoyed Patel’s patronage. Modi told Vajpayee that since he had been away in Delhi as the general secretary in charge of several states, he had been out of touch with local politics. Even so, he agreed to spend ten days a month in the state. However, a short while later, Modi agreed to accept the CM’s position after being convinced by his mentor Advani to do so. Advani knew about Modi’s lack of administrative experience, but was very fond of him.

Finally, Modi was sworn in as chief minister of Gujarati on 7 October 2001.

At Panjim in April 2002, the national executive meet began, and a short while later, Modi took to the dais and said he would like to step down as chief minister over the riots. Immediately, people from several sides got up and said there was no need to do so.

Whether it was orchestrated or not, Shourie wasn’t sure. But, according to him, Vajpayee felt that it was a coup. Sensing that things were not going as planned, Shourie got up and described what had gone on between Advani and Vajpayee on the plane and the agreement they had reached thereafter.

But shouts kept emerging from the delegates: ‘It cannot be done! Modi cannot be allowed to go!’ Vajpayee immediately understood the situation, and said, ‘Let’s decide on it later.’ ‘It can’t be decided later, it has to be decided now,’ somebody shouted. And as if on cue, it became a slogan.

Shourie observed that Advani hadn’t said anything though he knew very well that Vajpayee wanted Modi out. Seeing things take a different turn, Vajpayee kept mum, opting against a confrontational stance. Perhaps, for all his bravery, he was worried about younger leaders publicly questioning his authority. He would never forget that humiliation.