Legendary sea kayaker breaks his silence in new book ‘Pacific Alone’

For a few months back in 1987, Ed Gillet was a global media sensation.

With little money or supplies, no support crew and an off-the-shelf sea kayak, the 36-year-old San Diego adventurer paddled alone nearly 2,500 miles from Monterey Bay to Maui in 64 days. No one has ever equaled his feat, before or since, despite numerous failed attempts.

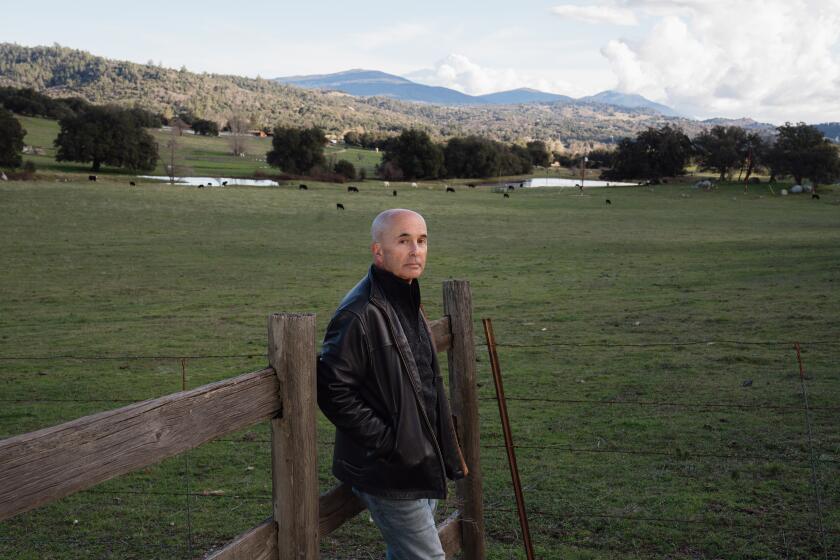

Yet while the 67-year-old Clairemont resident’s name is legendary in kayaking circles, it has long since disappeared from the public eye. And that’s by design.

Gillet, a longtime local high school teacher, said he wearied quickly of the misunderstandings and media circus that followed his trip so he went silent for more than a quarter-century.

Then in 2013, he got a call from longtime Canoe & Kayak Magazine writer/editor Dave Shively. He persuaded Gillet to tell his story at last, first in the magazine a few years ago, and now in Shively’s just-published book “The Pacific Alone: The Untold Story of Kayaking’s Boldest Voyage.”

Gillet said he trusted Shively with his story because the 37-year-old author is not only an expert at the language of kayaks and the sea, he also understands why Gillet felt compelled to test the limits of his endurance 31 years ago.

“Back then, I was portrayed as this crazed loner who pulled the whole thing off by luck,” Gillet said. “I got tired of trying to explain it. The thing is, I did it for the hell of it. It was where I was at the time.”

Shively first heard about Gillet in 2012, when a Bay Area kayaker named Wave Vidmar asked the magazine to sponsor his attempt to re-create Gillet’s 1987 crossing. Widmar aborted his attempt in stormy weather after just one day. A year later, a pair of Oakland air marshals attempted the same crossing together. They, too, failed within 24 hours.

“They were obsessed with Ed Gillet’s trip and they didn’t make it past day one. I figured out the real story wasn’t them, it was Ed,” said Shively, who is content director for TEN: The Enthusiast Network’s Paddlesports Group in Carlsbad. “In the first 10 minutes of talking to him about his approach to the trip, I was hooked. This was an incredible story.”

Shively used Gillet’s personal recollections as well as the weathered and much-treasured journal Gillet kept during the Pacific Ocean crossing to craft the 165-page book. Gillet said he once tried to write his own book but couldn’t capture his emotions the way Shively has.

“I could never re-create to my satisfaction the feeling of exhilaration and terror at the same time. It was like walking a tightrope,” he said. “Dave had that psychological distance to approach it and the writerly craft.”

The first time Gillet traded a boat for a kayak was in 1981 and he was blown away by how quietly the craft moved through the water, allowing him a more intimate connection with the environment. Over the next six years, he paddled nearly 20,000 miles up and down the Americas, from Peru to Alaska.

After dangerous encounters with soldiers, smugglers and angry villagers on the coast of Chile and Ecuador in 1984, Gillet decided to plan an epic trip where he could avoid people altogether and the idea for the California-to-Hawaii trek was born.

The trip was never designed to set a world record, land sponsors or attract media attention. It was simply a voyage Gillet felt he could afford and was capable of accomplishing while still pushing the extreme limit of his physical and mental abilities.

Back then, there was no Internet for research. For tips and advice, Gillet devoured the few books and magazine articles he could find on solo sea-crossings. It was challenging.

“I was never a meticulous planner,” he said. “When I planned kayak trips, I just threw stuff in and then threw in some more and off I went.”

On a kayaking trip in Sausalito in October 1985, Gillet fell in love at first sight twice. First, when he met his future wife, Bay Area competitive rower Katie Kampe, and later when he saw a 20-foot yellow tandem Tofino sea kayak made by Czech-born craftsman Mike Neckar.

In 1986, Kampe relocated to San Diego to move in with Gillet. She ran a small rowing business near Shelter Island, while he led group kayak trips to pay off the Tofino and other equipment for his trip. A few months before his voyage, they got married at Torrey Pines State Park and opened a new business, Southwest Kayaks.

Gillet said he could never have accomplished what he did without the strength and support of his wife, a lifelong sailor and adventurer herself, whose father was a silver star Army colonel. “Her dad was tough as nails and she comes from that hard-as-nails tradition,” Gillet said.

With zero fanfare, Gillet paddled out of Monterey Bay on June 25, 1987. His Tofino, later nicknamed “Dolphin,” was riding low in the water with 600 pounds of gear and food. His goal was to reach Hawaii in 45 days max.

His pack included two plastic sextants to navigate by the stars, a battery-powered knot-ometer to measure speed, a borrowed seawater purification system for drinking water, two cooking stoves, a weather radio, a navigation calculator and five watches. There was no GPS system, no ship-to-shore phone and the emergency beacon he installed to reassure Kampe of his progress shorted out nine days into the voyage.

Shively said Gillet’s trip is unique in how truly disconnected he was from the outside world and how he accomplished the trip on a scant $7,000 budget.

“Today, some people distort the process by making it so high-tech,” Gillet said. “I wanted a trip with purity. It doesn’t cost a lot of money to be pure.”

Most solo sea crossing attempts from California usually fail quickly in the rough coastal waters known as the “potato patch.” During the first week, Gillet struggled with stormy seas, extreme cold, saltwater sores, seasickness, lack of sleep and multiple equipment failures. On day 8, he decided to give up and turned his kayak toward San Diego. But that moment of resignation lasted only a few hours.

“It works on your mind. Things seemed way too marginal,” he said of the hardship in his first week. “Then I thought, ‘what the hell?’ When was I going to get to do this again? This is it. It’s all or nothing. So I turned around.”

On Day 13, the gray clouds finally lifted and by day 32, the long-anticipated trade winds began to blow, dramatically increasing the distance he covered each day. It was thrilling and beautiful out on the open sea and he cherished the solitude.

When the winds died, Gillet would increase his paddling to 16 hours a day. Because he could never stretch out completely in his kayak, he slept very little. By day 49, fatigue, anxiety and despair caught up with him and he vowed that if he survived, he wouldn’t ever talk about the trip.

“There was something sacred about it,” he said.

Gillet said that whenever he became overwhelmed at the sheer number of miles ahead, he would take a break and eat. Focusing on his meal, one bite at a time, allowed him to think and live in the moment.

As food stores ran low, he was lucky to catch the occasional mahi-mahi from a school that followed his kayak for hundreds of miles. Eventually, he rationed himself to 500 calories a day, ate his toothpaste and ran out of food on day 60.

Three days later, he spotted the mountains of Maui and paddled for 40 straight hours to arrive at Kahului Bay at dawn on Aug. 27. Although he was 19 days late, Gillet expected to see his family waiting onshore, unaware that the beacon had malfunctioned and they had no idea where he was or even if he was still alive.

So, he pulled the kayak ashore, called his family from a nearby hotel lobby, bought $22 of ice cream and snacks and settled under a tree to relish the moment.

“I was more at peace in that moment than I’ve ever been in my life,” he said. “It was complete happiness being there. I could’ve camped on the beach for days.”

As word of his arrival spread, Gillet was featured in local and national newspapers. “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson” flew him, Katie and the kayak to L.A. for a TV appearance. He gave the occasional lecture and slide show. Then, after a few months, he simply stopped.

He was tired of the stupid questions (“How did you go to the bathroom?” “Where did you land at night?”); reminded about how close he came to death; and troubled by the worry he’d caused his family.

Although the great solo adventuring was over, Gillet continued leading group kayak trips for the next 20 years. Kampe was diagnosed with cancer at an early age and has had many health challenges over the years. In 2001, they closed their kayak shop. Gillet is in his 18th year of teaching English and advanced placement literature, now at Eastlake High in Chula Vista. The “Dolphin” kayak now hangs in a place of honor at the Mission Bay Yacht Club.

Sometime in the not-too-distant future, Gillet and Kampe plans to sell their home and buy a boat that will be their home for the rest of their days. They plan to start with a year in the Sea of Cortez, then explore the Atlantic Ocean and beyond.

“I want to simplify my life,” Gillet said. “I’m looking for a more peaceful and quiet life. I want to get back some ground level of being in nature again. The middle of the ocean is a miraculous place to be. There’s no lights and a globe of stars over your head. I want to voyage on the ocean again.”

“The Pacific Alone” can be purchased at Barnes & Noble bookstores, REI stores, on Amazon.com and on Booksamillion.com.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.