Sky Views: China has won the internet's future

Wednesday 18 October 2017 09:04, UK

Tom Cheshire, Technology Correspondent

This summer, the Ethiopian government came up with a novel way to help students; it switched off the internet for a week.

"The only reason is to help our students to concentrate on the exams because we know we are fighting poverty," the country's communication minister said.

Such pastoral concern for young people is heartwarming but it probably had more to do with anti-government protests which started last year. Authorities cut off access to social media sites; blocking access to the entire internet was the natural next step. They also implemented a state of emergency, making it "illegal to post or access information about the protests on social media as well as communicate with outside forces".

There is only one internet provider in Ethiopia and it's controlled by the government. The country is one of the most digitally repressive: it's ranked fourth worst in the world for internet freedom, after China, Syria and Iran.

China doesn't just top that list - it has long been trying to export its model of the internet worldwide. As Iginio Gagliardone notes in The Politics of Technology in Africa: "It was through its revamped collaboration with China that the Ethiopian government was able to expand access to fixed and mobile phones and to the Internet under monopoly, maintaining a control on the flow of information in the country that no other African nation had achieved before."

Western governments' investments into African internet infrastructure came with conditions on freedom of expression and other human rights. China simply provided a blank cheque, no matter how authoritarian the government. Other African countries such as Sudan and the Gambia, which score badly on internet freedom, have received substantial Chinese investment.

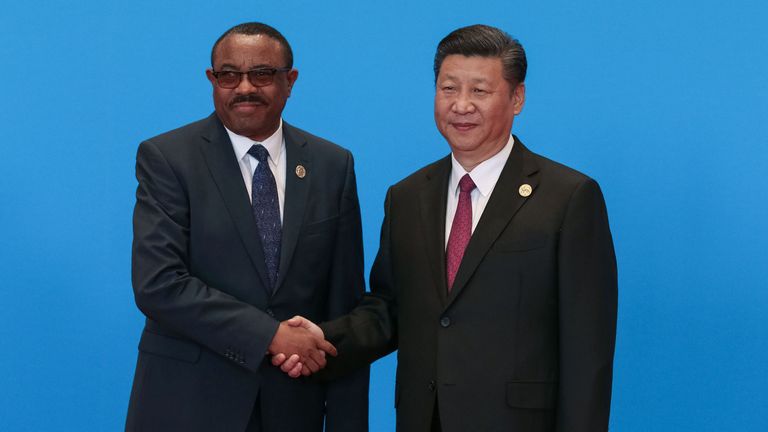

In Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe has hinted at a crackdown on social media ahead of elections next year. His spokesman cited China as an example to follow, a country which had "done well in ensuring some kind of order and lawfulness in that area". In 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping went to Zimbabwe to announce investment in its internet infrastructure, among other deals.

China pioneered a very different conception of the internet. The Communist Party managed to exclude the Silicon Valley giants that have carved up the rest of the digital world. Instead, homegrown services like WeChat, which has one billion users, dominate. The government has access to all those users' data. If you type a banned word or phrase in a group message, it simply won't appear on the other person's phone. Censored terms include 'Tiananmen Incident' and even 'Winnie the Pooh', after internet users spotted a physical resemblance between President Xi and the bear of very little brain.

Before any other government, China realised that the new digital states being founded - the 2 billion-strong population of Facebook; the 1.5 billion citizens that make up the nation of YouTube - posed a threat not just to its control, but its very sovereignty. (It's notable that the only American tech giant to have success in China is Apple, which poses no direct challenge to the state).

A founding document of the early internet, A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, made that explicit. It called on the "Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel", to leave the internet alone: "You have no sovereignty where we gather".

China ignored that appeal. According to Huang Yuan, writing in the London Review of Books: "When the internet first appeared, many people, including some Chinese, were optimistic about horizontality, elective mass communication, free flows of information and the empowerment of the individual voice, but it has since become clear that the internet has very little to do with freedom and much more to do with control."

For a long time, China was forced to export that model through expensive infrastructure investment. But now the West is following suit of its own accord.

Platforms like Facebook have realised too late the immense political power they wield, comparable to a nation state. Mark Zuckerberg has admitted that its adverts influenced the US presidential election and said that, as a result, it had worked hard to ensure fair elections in Germany.

This is quite the journey for a web app that started as a hot-or-not service but it's what China anticipated long ago. Both those on the left and right in the US - including even Steve Bannon - want to regulate Facebook and Google.

In the UK, the government constantly puts pressure on technology companies to "do more" - to prevent radicalisation, to detect and censor inappropriate posts from their users, to keep children safe online - the traditional functions of democratically-elected government. But the British state is also taking back control: the Digital Economy Act, passed in April this year, bans citizens' access to perfectly legal websites that don't meet its requirements.

We're edging closer to the Chinese model. Perhaps because we've realised, with the original freewheeling dream of cyberspace gone, there's not much to choose between the Chinese approach and Facebook, Google and the rest.

Both models of sovereignty - rule by an authoritarian state or rule by digital platform - rely on surveillance, whether in the service of political control or of free-market capitalism.

For a long time, the Chinese approach to the internet appeared to be a relic of a repressive past. These days, depressingly, it looks like the future.

Sky Views is a series of comment pieces by Sky News editors and correspondents, published every morning

Previously on Sky Views: Katie Stallard - China is on road to repression