It’s no surprise Terry Reid doesn’t want to talk about the one subject people never fail to bring up to him. Namely, his 1968 decision to turn down Jimmy Page’s offer to front a new band, later to be called Led Zeppelin.

“It’s a waste of time to talk about it,” he told the Observer last week. “They did really well. End of story.”

But that’s hardly the end of the Terry Reid story. His is one not nearly enough people know about.

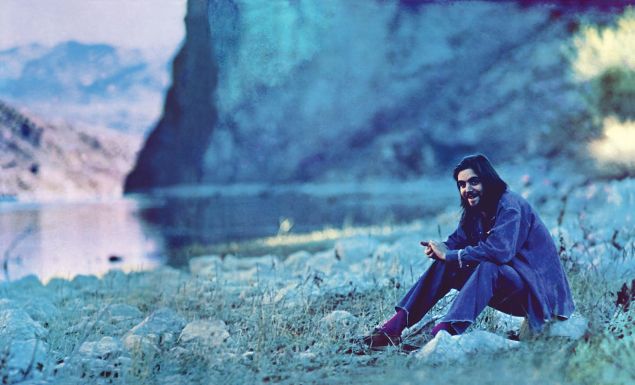

Reid—who owns one of the most emotive, and distinct, soul shouts known to man—has a labyrinthine tale that snakes through the history of both British blues and Laurel Canyon folk-rock. Along the way, his sound has taken stops in Brazil, Nashville and Puerto Rico. It also features connections to a long list of seminal artists, including Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Gilberto Gil, The Rolling Stones, and the guy he just recently began working with—Joe Perry of Aerosmith.

Back in the day, Jimmy Page wasn’t the only musician who pined to harness Reid’s burly rasp and deep well of feeling. Deep Purple tried to hire him too, right before they tapped Ian Gillan in 1969. “I was asked to join a lot of bands,” Reid said matter-of-factly.

“There are only three things happening in England: The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and Terry Reid.”—Aretha Franklin

Small wonder, at that time, Aretha Franklin noted, “There are only three things happening in England: The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and Terry Reid.”

This week, listeners receive fresh evidence of Reid’s power and breadth with the release of The Other Side of The River, from stalwarts of pristine esoterica Light in the Attic. The set collects precious outtakes from Reid’s third album, 1973’s River, a work which stands among the most under-appreciated, and adventurous, collections of its day.

Reid’s first two albums—1968’s Bang Bang…You’re Terry Reid, and Move Over for Terry Reid, released the next year—concentrated on a bluesy and hard-rocking sound, reminiscent of the early Jeff Beck Band. He took a sharp turn away from that on River.

The visionary disc weaved in elements of folk-rock, jazz, blues, country and even tropicalia. The result sounded like some lost cousin to works of the day by Tim Buckley, Van Morrison and John Martyn. The just-discovered material from those sessions derives, in some part, from the album’s complicated creation. “We had to record it twice,” Reid said. “So things got real interesting along the way.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yM7MFalV4vg&w=560&h=315]

Reid started making River in 1971 in his native England, with producer Eddie Offord, drummer Alan White (late of John Lennon’s Plastic Ono band) and David Lindley, fresh from a little-known psychedelic-rock band named Kaleidoscope. That band just popped back into the public eye via an unlikely source: Beyoncé. She sampled a huge part of the Kaleidoscope song “Let Me Try” for her new track “Freedom.”

Lindley, perhaps the world’s most graceful lap-steel guitar player, first came to Reid’s attention through a friend, who managed Jefferson Airplane. “David wrote me a letter and said, ‘I’d like to bring all these instruments over.’ And the list was like a bloody toilet role,” Reid said, with a laugh. “Some of the instruments I didn’t even recognize. The guy is brilliant.”

Unfortunately for Reid, he wasn’t the only one who recognized that. An earlier recording Lindley had made with Jackson Browne, “Doctor My Eyes,” which prominently featured the musician’s guitar, shot up the charts in ’72. So the L.A. songwriter hired Lindley away for a big tour. At the same time, White got hired by Yes to replace Bill Bruford (who’d left to join King Crimson), and producer Offord went off with him.

As it happened, Reid was pining to get out of cold, rainy England to move to the warm U.S. West Coast (where he lives to this day). An offer to travel stateside to work with Tom Dowd, the legendary producer at Atlantic Records, sealed the deal. With Dowd, Reid reworked the music for River in L.A. Inspired by Reid’s love of Latin rhythms, Dowd brought in Puerto Rican percussionist Willie Bobo. The music already bore some worldly imprint from Gilberto Gil, whom Reid had met a few years earlier. In fact, it was Reid’s attorney who arranged for Gil to get out of Brazil, which was then a police state. “He got his whole family out of Rio in 24 hours,” Reid said. “This was serious business down there.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WyUnWvkhIJw&w=560&h=315]

Reflecting that connection, the new River collection features a track named “Country Brazilian Funk,” which finds an improbable connection between Gil’s south of the border sound and Lindley’s American flair.

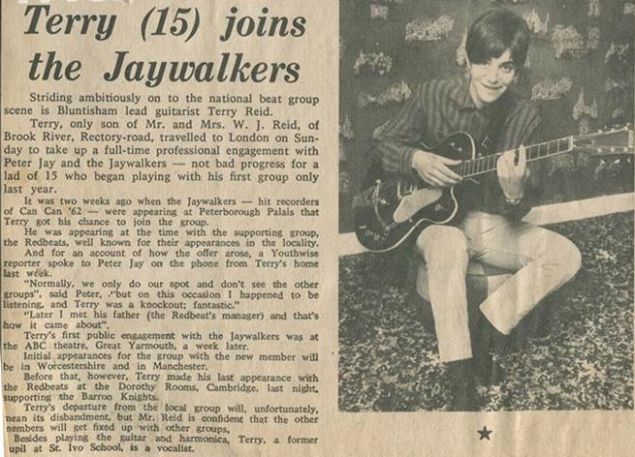

Such leaps show how willing the young Reid was to take risks. He was just 23 at the time. When he cut his first two, harder-rocking albums, he was still a teenager.

The famously controlling British manager Mickie Most had signed the kid back in ’68 to a terribly binding contract. For some reason, Most decided Reid’s debut album should only come out in the U.S. (not the U.K.) It’s an inconsistent work, but it features Reid’s astoundingly loud voice on covers of songs by Donovan (also managed by Most) and Sonny Bono (“Bang Bang…My Baby Shot Me Down”). Reid also wrote great songs of his own for the album, like the explosive “Tinker Tailor.” “It’s more or less just the band live in the studio, no frills” he said.

It was around this time that Page made his famous offer.

Not only did Reid already have his own career starting up, he had previously committed to a tour with The Doors and Jefferson Airplane. Though he’s terse in talking about it, Reid admitted that he didn’t exactly turn Page down flat. “I told him, ‘if you want to do it, wait a couple of weeks. I’ll be back from the tour and we can give it a shot,’ ” Reid said. “But he wanted to do it right then.”

“I just told Richie Blackmore, ‘that hard rock is not my thing.’ I call it ‘cock-rock.’ I was going into writing sambas at that time and you can’t do that in spandex.”

Ever gentlemanly, Reid suggested Page check out a singer whose group (Band of Joy) once opened for Reid—Robert Plant. “And the rest is history,” he said.

By contrast, Reid says he never seriously entertained the Deep Purple offer. “I just told Richie Blackmore, ‘that hard rock is not my thing,’ ’’ he said. “I call it ‘cock-rock.’ I was going into writing sambas at that time and you can’t do that in spandex.”

In fact, Reid had already been giving hints of his expanding style.

His first two albums included songs like the dreamy ballad “July” and the jazzy “No Expression,” later covered by The Hollies and John Mellencamp. He received the most attention, however, for his shattering cover of the soul song “Stay With Me (Baby),” included on his second album. Reid’s tour-de-force vocal could out-yell Janis Joplin and Joe Cocker combined. It remains one of the most searing torch ballads ever recorded, far outstripping the better known take by Bette Midler in “The Rose.”

The result gave Reid the nickname “Super Lungs.” It helped that the phrase was also the title of a song he covered by Donovan, about a 14 year old girl with a talent for taking deep tokes of pot (among other things).

Interestingly, “Stay With Me” has just resurfaced via a cover by Chris Cornell in the HBO series Vinyl. In interviews, Cornell has acknowledged his debt to Reid’s classic version. “When I first heard the organ intro, I thought they used my recording,” Reid said. “I thought I was in for a few bucks. But he did a good job.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jW9mDyFgh1o&w=420&h=315]

For all the buzz and respect Reid had back in the day, his career never broke big. Even serving as the opening act for The Rolling Stones on their pivotal 1969 tour didn’t do the trick. Reid’s nearly ruinous contract with Mickie Most delayed the release of River until four years after his previous album.

Three years later, the singer recorded a rootsy, and revered, work titled Seed of Memory, produced by old friend Graham Nash. But his record company experienced an implosion upon its release, killing its commercial opportunities. Reid recorded two other studio albums, Rogue Waves, in ’79, with a hard-soul sound, and The Driver, in ’81, marred by then-trendy new wave production.

In the ensuing years, Reid worked as a backup singer, and toured regularly on his own.

In 2013, he put out a Live In London set, which proved he still had the pipes. It featured everything from a convincing cover of a Frank Sinatra song to a take on one of Reid’s best known early compositions, “Rich Kid Blues,” a song later recorded by Marianne Faithfull and Jack White.

The live album shows the kind of breadth a singer can only achieve shorn of the compromises and constraints of being in a hit band. That helps explain why, at 66, Reid has no regrets. It also helps that he has an exciting new project going. Reid’s old friend, Jack Douglas, producer of all the classic Aerosmith albums, connected the singer to Joe Perry, who’d been looking for someone to write the melody lines for a new solo album.

So far, Reid has cut four tracks with Perry for that project, which will also feature Johnny Depp. The new music returns Reid to the hard guitar sound of his teen years. Apparently, Perry and Depp were so impressed by the singer, they’ve vowed to make their next project a Reid solo album. It will be his first full studio work in 25 years.

In the meantime, the release of The Other Side of The River underscores how freely the singer’s muse has always roamed. “The only thing to connect all the songs I’ve sung in my career is that I’m singing them,” Reid said. “There’s no fucking point in making the same old bloody record over and over. It’s always important to move on.

***

READ THIS: For Your (Re)Consideration: What Was the First Punk Record?