In 2019, a song called “Cola” began taking over international airwaves largely thanks to its inclusion on Pollen, Spotify’s genre-less hit playlist. Featuring a soulful, soothing voice deceivingly at odds with the track’s melancholic prose about romantic betrayal, it kick-started the rise of a breakout talent who has given a voice to the anxieties and aches of an entire generation: Arlo Parks.

Born Anais Oluwatoyin Estelle Marinho in West London, the 20-year-old musician got the attention of industry executives by uploading her demos to BBC Music Introducing in 2018. After the initial success of “Cola,” which she released as her first single at the end of that year, her debut EP, Super Sad Generation, arrived in April of 2019, followed by another EP, Sophie, that November. Addressing unemployment, addiction, depression, mental illness, and suicide, the collections of songs were inspired by Parks’s own experiences and inner circle but reflect larger issues plaguing young people around the world.

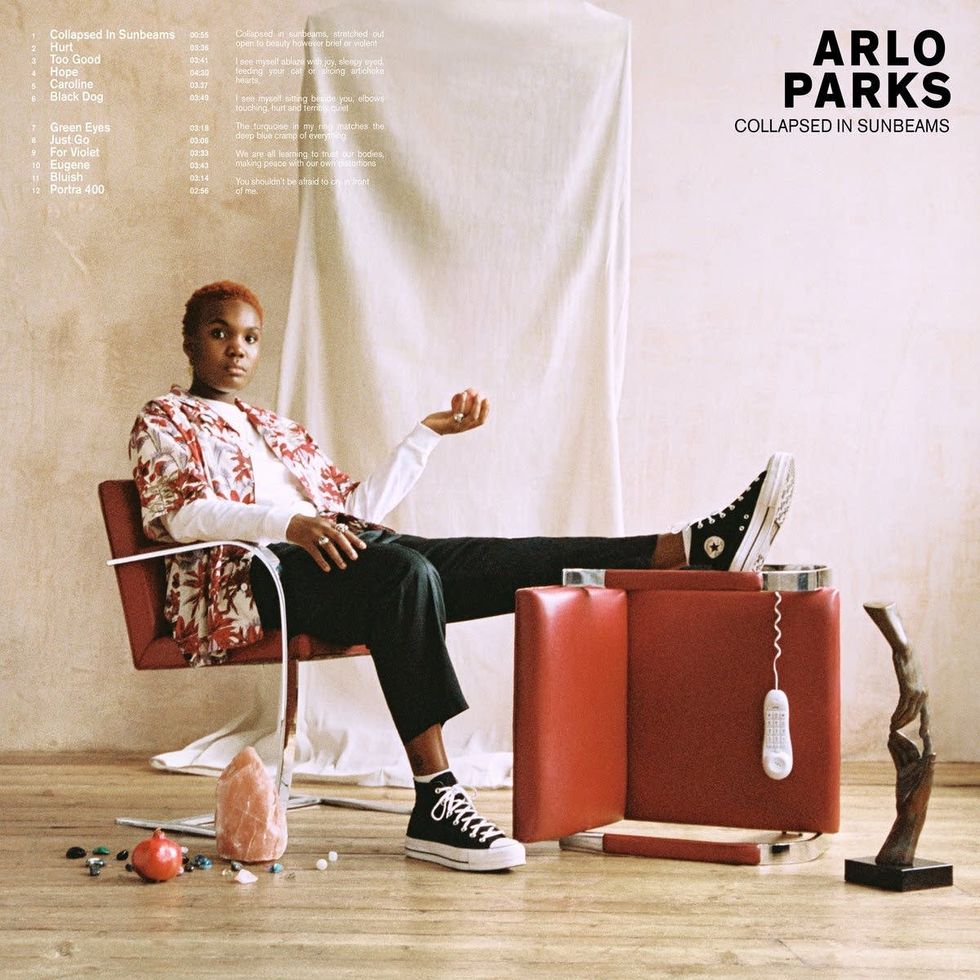

On January 29, Parks releases her first full studio album, Collapsed in Sunbeams, which once again wraps difficult realities in warm, reassuring melodies. As she explains, “I really want people to see their own stories in the ones that I’m detailing.”

Over the phone in late 2020, calling from her family’s West London home, Parks spoke with BAZAAR.com about the new record, life in lockdown, and why molds are meant to be broken.

London is in its second major lockdown—what have you been doing to keep occupied, and how has this phase been different from the first?

This time around, because I've written the album, it's more of an opportunity to recharge my creative batteries. I've just been absorbing art. I've been reading a lot of poetry that I hadn't read before, and I've been watching a lot of art-house movies and Korean films. I just finished Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion, which I really, really enjoyed. My favorite movie so far has been In the Mood for Love, which is directed by Wong Kar-wai, and I've also enjoyed this film called 8½, directed by [Federico] Fellini. I've been expanding my horizons a bit, and it's been very much an opportunity for me to absorb things rather than just expand content.

When the pandemic hit, you were finishing up your first solo tour. Was it jarring to go from being around tons of people all the time to suddenly being relatively isolated?

The tour was an amazing experience, because I managed to do all but two of the shows. Being able to create that space that felt safe and where I could express myself however I wanted and read poetry and talk to people—that was probably one of the highlights of 2020. There was that sense of human connection, which unfortunately, we don't really have now.

It was definitely quite jarring when it ended, because when you're on tour, you're in the van, you're surrounded by people constantly, not even just at the show. And then it went from that to that sense of being by yourself and spending a lot of time with yourself and having those periods of introspection. But for me, I was glad to feel inspired during that time.

You were touring with music from both Sophie and Super Sad Generation, which are both about adolescent angst. How do they differ?

Super Sad Generation was essentially about the struggles that you go through when you're growing up in the world and trying to figure out what kind of person you want to be. It's about spending time with friends and that sense of feeling carefree, but also the anxieties that come with getting older.

Sophie, my second EP, was almost an evolution of that. I write based off of what I'm seeing around me and my writing is based in storytelling, so "George" tells the stories of some of the friends who were around me and the struggles that they had been through. It kind of details these portraits of other teenagers that I was growing up around and of my own ideas about the world.

Do you think that your generation in particular is facing more anxieties specific to the effects of social media?

I definitely think social media does cause this desire to be perfect. It can make kids feel like they've got quite a lot of the weight on their shoulders in terms of how they're supposed to be and what they're supposed to like and how they're supposed to act. I think it pressures you to make you feel boxed in.

You’ve spoken before about struggling with your identity when you were younger. What kinds of things were you navigating?

When I was younger, there was that desire to be cool and to fit in and to look a certain way. And I was quite an introverted kid who wrote plays in her spare time, so I didn't feel very cool. It was that idea of navigating what was accepted in the world and feeling outside of that in a lot of ways. But then over time, as I discovered music and art, and how broad those worlds are, and fell in with people who had similar interests and ambitions, that's when I realized that there's no such thing as cool. The mold is there to be broken.

What other artists inspired you in your musical and personal growth?

When I was younger, there was a lot of soul playing in the house. So Otis Redding, Minnie Riperton. I think the big artists that got me wanting to make music were people like Portishead and the kids from Odd Future, so Earl Sweatshirt and Tyler [the Creator] were very inspirational to me. Also, King Krule. When I heard 6 Feet Beneath the Moon—it came out when I was 13, I believe—it struck me. The gravelly nature of his voice and the gritty poetry and the sparse arrangement—it was completely magnetizing. The fact that he was just a kid from South London—it just felt very raw. You could see that he was writing from the heart and doing what he wanted to do with his work, and that was super inspiring to me.

When did you start working on your debut studio album, Collapsed in Sunbeams?

It was written and recorded in apartments, essentially. Most of the songs on it were written in January [2020]. We spent a week in this Airbnb just making pasta, writing, recording. And then we had another two weeks during lockdown where most of the record was made. Those were the sessions where I would say a good 70 percent of the record was made. I also did a few sessions with [producer] Paul Epworth and this group called Bad Sounds, where we fleshed out some demos that I had sent their way. In total, it probably only took a few weeks to write this record. I usually just write a song and record it that day, and then that's kind of it. I'm not very good at going back and editing and tinkering it. It's pretty immediate.

Did it feel strange to be working on your album while the world was in such a sad, unprecedented place?

For me, whenever the world does feel chaotic, I always turn to art. I always turn to writing. It felt like the most natural thing in the world to me. I know what you mean though, because there was this sense of, "There's a literal pandemic, what is the function of art? Should I even be writing? What's happening?" But I just kind of clung to my creativity, and it felt quite comforting. It felt like I was almost in the eye of the storm.

You’ve described the album as a series of portraits surrounding your adolescence. Can you describe a few?

The song “Hope” is essentially a portrait of somebody who is going through a very low period of time and her relationship with her family. The crux of the song is the idea of you're not alone. I think when you're in those lowest spaces, you can feel completely isolated, and it's almost like a reminder, a mantra, that you're not alone. I hope it uplifts people.

And the song “Bluish,” that's based around the idea of needing space, the idea of feeling claustrophobic in a relationship, whether it's romantic or not. And the importance of setting boundaries and ensuring one is protecting themselves from becoming codependent.

Clairo features on “Green Eyes” from your album. How did that collaboration happen?

We worked across the Internet. I am a massive fan of her work and her voice, it’s so quietly confident and delicate. I really wanted her to be a part of the song, and so I reached out to her on Instagram and asked her to do harmonies, and she kindly agreed. She just had an instinct to add a guitar line at the very end of the song. I think it was kind of spontaneous—it just came from within. It added this kind of ethereal, nostalgic dimension that almost was the cherry on the cake with this song.

You and Clairo both launched your careers on the Internet, and in a way, it’s democratized music. How do you think it’ll continue to shape the industry?

I think that it's a beautiful thing. Even in terms of the music-making process, you don't need to have a fancy studio anymore. Most of Collapsed in Sunbeams was produced with guitar bass and a computer. The fact that anyone can get themselves out there means that music and creativity are more accessible, you don't necessarily need to have tons of money. That warms my heart. Also, with things like Instagram, I can connect with people from all over the world. Collaboration is one of the most fun and special parts of making music, so it's definitely a positive thing.

What is the main thing you want people to take away from the album?

I want people to feel seen, and I want people to feel soothed by the music. I think music is really a healing force, and I hope that people feel that way when they listen to mine. Also, I just want people to be affected by it. The albums that stand out are the ones that you can't forget. That's what I'm aiming for.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Ariana Marsh is Harper Bazaar’s senior features editor. Working across print and digital, she covers the arts, culture, fashion, literature, and entertainment—and a bit of everything in between.