It Was Supposed To Be Easier To Get Out Of Jail In LA. But Bail's Not Dead Yet

THIS STORY IS PART OF HOW TO L.A., OUR ONGOING SERIES OF PRACTICAL GUIDES FOR DAY-TO-DAY LIVING IN LOS ANGELES.

UPDATED Jan. 17 --

The bail bond industry has found a way to put a hold on a California law that would have put bondsmen out of business. The law, Senate Bill 10, passed last year and was scheduled to go into effect in October 2019, and would have ended cash bail in the state.

But on January 16, a bail-bond-industry-backed ballot initiative qualified for the November 2020 ballot that would roll back SB10. And under state law, that means SB10 is on hold until voters get a chance to weigh in on the future of bail in California.

Bail has been around a long time. In fact, the concept predates the creation of the United States of America.

So why do some people say it's time it went away?

The movement to eliminate commercial bail (that's when you get a bond agent to put up the money the court requires to get out of jail) has been growing. California is at the center of a lot of that debate. Here in Los Angeles, any changes to the bail system would have a huge impact.

Consider this: Nearly 111,000 people were booked into L.A. County jails last year. Charges ranged from trespassing to murder. Some of those jailed are serving a sentence. But a lot (about 42 percent of inmates on any given night) are awaiting trial.

That's where bail can come in. Here's how it currently works in Los Angeles -- and what could come next.

THE BAIL SCENARIO

Sometimes a judge will determine that a defendant must stay in jail while the case plays out in court. In other cases the law requires a defendant to stay in jail while the case plays out.

Then there are the cases where people are released on their "own recognizance" to go back to their jobs, families and homes while dealing with their charges.

Then there's the bail scenario.

In these cases, a defendant can leave jail while the court case proceeds, if he or she puts down a chunk of cash -- a financial guarantee that the person will show up in court when called.

The defendant can either put up the cash, or, for a fraction of the full bail amount, hire a bail bond agent to do so.

Here's the catch: a lot of people simply can't afford to make bail.

On any given day last year, about 7,000 people were sitting in L.A. County jails because they couldn't afford bail.

DETERMINING THE AMOUNT

Generally, the overall bail amount is set by a judge, who follows a "bail schedule" that outlines what bail should be for people accused of various crimes.

In L.A. County, bail amounts vary widely. Here are some examples.

A defendant, relative or friend can put up the full bail amount themselves. However, they risk losing the money if the defendant doesn't show up for court.

Other times, a bail agent is hired.

Bail agents generally charge 10 percent of the bail amount as a fee, and will likely require collateral for the balance (think: house, car or bank accounts). The bail agent is then responsible for paying out the full bail amount if the client doesn't show up in court.

GETTING THE MONEY BACK

If a defendant (or that friend or relative) puts up the money, he or she can get it back after the court case ends.

If the person hires a bail agent, that 10 percent fee is nonrefundable. So, guilty or not, the price of freedom while awaiting trial can be hundreds or thousands of dollars.

BY THE NUMBERS

- The average bail amount for a defendant in a felony case, nationwide: $55,000 (according to a study published earlier this year in the American Economic Review)

- Defendants earned on average $7,000 the year before their arrest.

- Over half of defendants nationwide could not afford bail, even when bail was set at $5,000 or less.

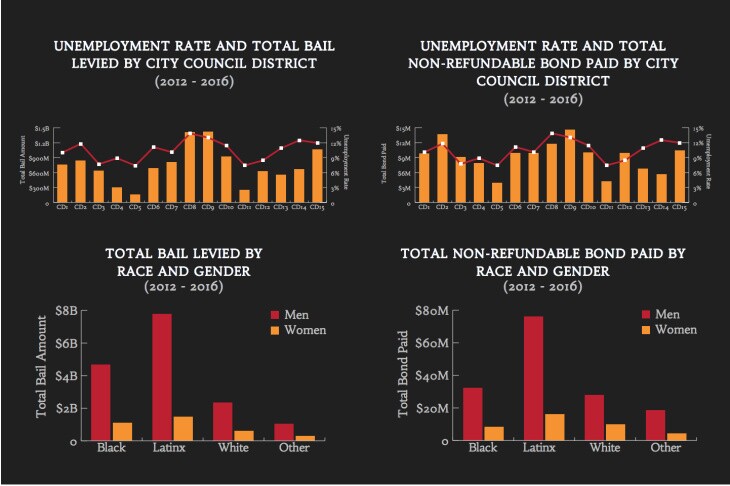

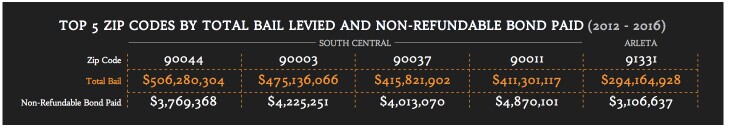

- Between 2012-2016, bail set for people arrested in L.A. County totaled $19.4 billion (according to a UCLA study published last year).

WHY IT WORKS

Privatizing the process for getting people to show up in court potentially saves law enforcement and courts a lot of time and money, as bail bond agents and industry groups tend to point out.

Bail bond agents have a financial incentive to make sure their clients show up to their hearings. Ideally, this means fewer warrants are issued for no-shows, fewer rescheduled court dates, fewer instances where police have to expend resources to hunt down someone who's skipped out.

So commercial bail costs taxpayers nothing and provides a system for releasing people from custody while they're awaiting trial.

WHY THERE ARE PROBLEMS

A number of experts argue that bail is fundamentally unfair and doesn't do much for public safety.

The main reason: An objectively more dangerous person could be walking the streets because he has money, while a less dangerous person sits in jail because he can't afford bail.

For example, a defendant who can afford bail who's been accused of domestic violence or sexual assault can get out of jail while the case progresses through the legal system -- which could take years. Meanwhile, someone accused of burglary or indecent exposure could sit there because they don't have bail money.

To make matters worse, that UCLA study on bail in L.A. County found "the greatest sums of money bail were levied in the City Council districts with the highest rates of unemployment." On top of that, it said, "nearly four billion dollars in money bail was levied on houseless persons."

There are other issues: a jailed defendant's children have to be either left with relatives or friends or enter the child welfare system; people who are held in jail can lose their jobs, and it can be difficult to reenter the workforce, which can set a family back financially for some time. Even a few days of incarceration can dramatically affect a person's life.

Then, there are questions of justice.

PLEADING GUILTY

There are also indications that people who get stuck in jail because they can't afford bail might be more likely to plead guilty.

A study published in the American Economic Review earlier this year by researchers from Stanford, Princeton and Harvard found that sitting in jail while legal proceedings play out makes a person 14 percent more likely to be convicted or plead guilty, while being released while fighting a case makes a person 11 percent less likely to plead guilty.

When it comes to plea deals, being at home as opposed to jail benefits defendants "primarily through a strengthening of defendants' bargaining positions before trial," the study said.

The psychology behind that is clear, particularly for lower level cases: plead guilty and we'll ask for a sentence of "time served" so you get out now, or fight your case and sit in jail while it plays out.

SO WHAT HAPPENS NOW?

Senate Bill 10, written by Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) passed last year and was signed into law by then-Governor Jerry Brown in August. The bill required counties to use risk assessment tools to determine whether a person charged with a crime needed to be held in jail while their case played out in court. It also gave judges broad authority to hold people in jail pending trial if they were charged with violent or serious crimes. The law has its critics:

-Bail bond companies say it's dangerous, because it potentially lets violent people out of jail and costly because it takes something that private bail bondsmen were doing and makes it the government's problem.

-Criminal justice reform advocates come at the law from the opposite side, saying it doesn't go far enough. It leaves too much power with local judges to detain people. "That means we're going to see more people detained in places like Fresno and Riverside than we do in places like San Francisco and Alameda County and that's just not fair," said Natasha Minsker of the ACLU. That said, criminal justice reformers are not expected to fight on behalf of the new ballot initiative. "The ACLU is never going to support the bail industry's efforts to keep themselves in business," she said.

The political fight promises to be heated. Voters will weigh in come November 2020.

In the meantime, however, there could be side effects to this delay in deciding on who and how people should be detained while they're awaiting trial, particularly in L.A. County.

That's because L.A. is currently soul-searching when it comes to updating and upgrading its county jail system, which happens to be the largest in the country. There are two major proposals for new jail construction--a women's jail in Mira Loma and a downtown correctional facility for inmates with mental illness. To a certain extent, what happens with bail in California has a bearing on how big those jails should be.

According to L.A. County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, about half of the women in jail in L.A. are pre-trial, meaning many would not be in jail if they could afford bail. At least 7,000 people in the county are sitting in jail on any given night because they can't afford bail.

Kuehl said more assessments are needed to determine how bail reform, as written in SB 10, would impact that population--and particularly a proposed new jail for women.

"They're low level offenders and about half of them haven't been tried yet, so I assume bail reform would make a difference in those numbers," Kuehl said. "I think the women's jail will probably end up being smaller than what we imagined."

Nothing stops L.A. County from pursuing its own bail reform agenda--that is, nothing besides politics and philosophical disagreements over what's good for public safety. Having a statewide bill firmly in place would make the process quicker and easier.

Kuehl, along L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis, who co-authored a motion in 2017 to pursue bail reform in L.A., pledged to continue the fight locally, regardless of what happens statewide.

"We are continuing to work towards developing a model for bail reform that meets the unique needs of our County, and reduces incarceration of people simply because they are poor," Solis told KPCC after the ballot initiative qualified. "The status quo is untenable."

UPDATES:

Aug. 28, 2018: This article was updated with news that Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill making California first state to eliminate cash bail.

Jan. 17, 2019: This article was updated with news that a ballot initiative challenging SB 10 qualified for the 2020 ballot, as well as information about the status of L.A. County's proposed jail construction projects.

This article was originally published July 17, 2018

Hey, thanks. You read the entire story. And we love you for that. Here at LAist, our goal is to cover the stories that matter to you, not advertisers. We don't have paywalls, but we do have payments (aka bills). So if you love independent, local journalism, join us. Let's make the world a better place, together. Donate now.

-

The action by authorities began about nine hours after the initial order to disperse was issued around 6:15 p.m. Wednesday. Shortly after 5 a.m. the area was cleared, with just a small amount of protesters remaining.

-

The project will rename most of the terminals and all of the gates with the goal of world-class signage that leans into psychology.

-

On campus, many students found USC's reversal to be puzzling.

-

The highly anticipated airport service likely won’t open until October 2025.

-

In her first public statements since controversy erupted over millions of unaccounted for tax dollars, Rhiannon Do says she’s no longer with the O.C. nonprofit Viet America Society. She also says she never had a leadership role. Public documents show otherwise.

-

After San Gabriel's city council rejected the proposal as "too narrow", one city councilmember argued the entire DEI commission, created in the aftermath of George Floyd's murder, had "run its course."