Dealing With an Out-of-Control President, in 1973

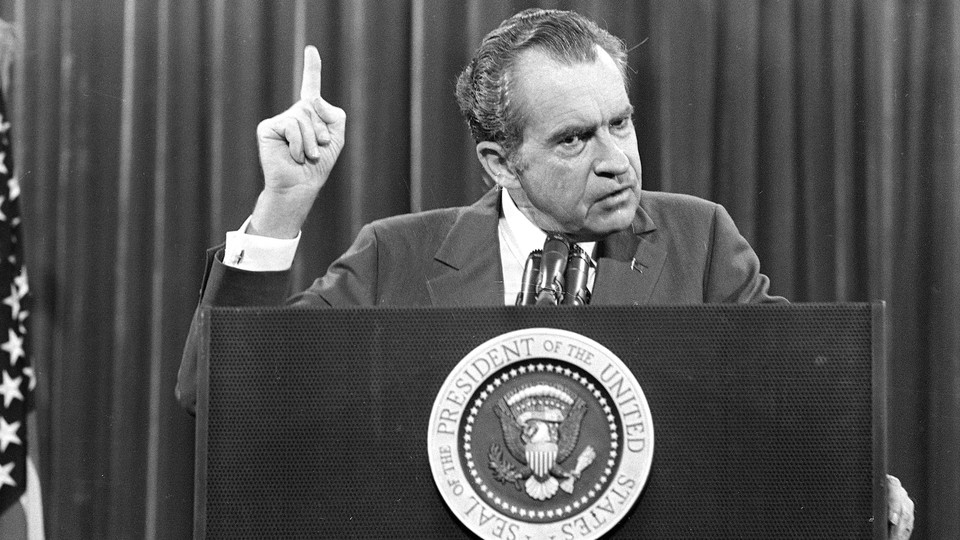

In the midst of the Watergate scandal, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. considered how Richard Nixon had abused the powers of the presidency—and how constitutional order could be restored.

Updated on September 14, 2018.

In August 1974 Richard Nixon would resign from the presidency after the Watergate scandal eroded his public support and Congress initiated impeachment proceedings against him. But in November 1973, the fate of his presidency was still uncertain; the full story behind Watergate was just coming to light, illuminating a historic “expansion and abuse of presidential power,” in the words of the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

At the beginning of Nixon’s downfall, Schlesinger analyzed how the president had corrupted and exploited the powers of his office for his own ends. He also explored why those abuses had remained, and might continue to remain, unchecked. “The Constitution cannot hold the nation to ideals it is determined to betray,” Schlesinger warned. “The great institutions—Congress, the courts, the executive establishment, the press, the universities, public opinion—have to reclaim their own dignity and meet their own responsibilities. … In the end, the Constitution will live only if it embodies the spirit of the American people.”

It was then becoming clear that the presidency was occupied by a man who was temperamentally unfit for his office, legally corrupt, and undemocratically inclined. But, as Schlesinger noted, he could be removed—and the office for a time “inoculate[d] … against its latent criminal impulses”—if citizens and their representatives met him with moral courage and a resolve to fulfill their constitutional duty. — Annika Neklason

I

“The tyranny of the legislature is really the danger most to be feared, and will continue to be so for many years to come,” Jefferson wrote Madison six weeks before Washington’s first inauguration. “The tyranny of the executive power will come in its turn, but at a more distant period.” On the eve of the second centennial of independence, Jefferson’s prophecy appears almost on the verge of fulfillment. The imperial presidency, created by wars abroad, has made a bold bid for power at home. The belief of the Nixon Administration in its own mandate and its own virtue, compounded by its conviction that the republic has been in mortal danger from internal enemies, has produced an unprecedented concentration of power in the White House and an unprecedented attempt to transform the presidency of the Constitution into a plebiscitary presidency. If this transformation is carried through, the President, instead of being accountable every day to Congress and public opinion, will be accountable every four years to the electorate. Between elections, the President will be accountable only through impeachment and will govern, as much as he can, by decree. The expansion and abuse of presidential power constitute the underlying issue, the issue that Watergate has raised to the surface, dramatized, and made politically accessible.

In giving great power to Presidents, Americans have declared their faith in the winnowing processes of politics. They have assumed that these processes, whether operating through the electoral college or later through the congressional caucus or still later through the party conventions, will eliminate aspirants to the presidency who reject the written restraints of the Constitution and the unwritten restraints of the republican ethos.

Through most of American history that assumption has been justified. “Not many Presidents have been brilliant,” James Bryce observed in 1921, “some have not risen to the full moral height of the position. But none has been base or unfaithful to his trust, none has tarnished the honour of the nation.” Even as Bryce wrote, however, his observation was falling out of date—Warren G. Harding had just been inaugurated—and half a century later his optimism appears as much the function of luck as of any necessity in the constitutional order. Today the pessimism of the Supreme Court in an 1866 decision, ex parte Milligan, seems a good deal more prescient. The nation, as Justice Davis wrote for the Court then, has “no right to expect that it will always have wise and humane rulers, sincerely attached to the principles of the Constitution. Wicked men, ambitious of power. with hatred of liberty and contempt of law, may fill the place once occupied by Washington and Lincoln.”

The presidency has been in crisis before; but the constitutional offense that led to the impeachment of Andrew Johnson was trivial compared to the charges now accumulating around the Nixon Administration. There are, indeed, constitutional offenses here too—the abuse of impoundment and executive privilege, for example; or the secret air war against Cambodia in 1969-1970, unauthorized by and unknown to Congress; or the prosecution of the war in Vietnam after the repeal of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution; or the air war against Cambodia after the total withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam. But these, like Andrew Johnson’s far less consequential defiance of the Tenure of Office Act, are questions that a President may more or less plausibly insist lie within a range of executive discretion. The Johnson case has discredited impeachment as a means of resolving arguable disagreements over the interpretation of the Constitution in advance of final judgment by the Supreme Court.

What is unique in the history of the presidency is the long list of potential criminal charges against the Nixon Administration. The investigations in process suggest that Nixon’s appointees were engaged in a multitude of indictable activities: at the very least, in burglary; in forgery; in illegal wiretapping; in illegal electronic surveillance; in perjury; in subornation of perjury; in obstruction of justice; in destruction of evidence; in tampering with witnesses; in misprision of felony; in bribery (of the Watergate defendants); in acceptance of bribes (from Vesco and ITT); in conspiracy to involve government agencies (the FBI, the CIA, the Secret Service, the IRS, the Securities and Exchange Commission) in illegal action.

As for the President himself, he has denied that he knew either about the warfare of espionage and sabotage waged by his agents against his opponents or about the subsequent cover-up. If Nixon knew about these things, he obviously conspired against the basic processes of democracy. If he really did not know and for nine months did not bother to find out, he is surely an irresponsible and incompetent executive. For, if he did not know, it can only be because he did not want to know. He had all the facilities in the world for discovering the facts. The courts and posterity will have to decide whether the Spectator of London is right in its harsh judgment that in two centuries American history has come full circle “from George Washington, who could not tell a lie, to Richard Nixon, who cannot tell the truth.”

Whether Nixon himself was witting or unwitting, what is clearly beyond dispute is his responsibility for the moral atmosphere within his official family. White House aides do not often do things they know their principal would not wish them to do—a proposition which I and dozens of other former White House aides can certify from experience. It is the President who both sets the example and picks the men. What standards did Nixon establish for his White House? He himself has admitted that in 1970, till J. Edgar Hoover forced him to change his mind, he authorized a series of criminal actions in knowing violation of the laws and the Constitution—authorization that would appear to be in transgression both of his presidential oath to preserve the Constitution and of his constitutional duty to see that the laws are faithfully executed. In 1971, as he has also admitted, he commissioned the White House plumbers, who set out so soon thereafter on their career of burglary, wiretapping, and forgery. “From the time when the break-in occurred,” he said of the Watergate affair in August, 1973, “I pressed repeatedly to know the facts, and particularly whether there was any involvement of anyone in the White House”; but two obvious sources—John Mitchell, his intimate friend, former law partner, former Attorney General, head of the Committee for the Re-Election of the President, and Patrick Gray, acting director of the FBI itself—have both testified under oath that he never got around to pressing them. He even, through John Ehrlichman, asked the Ellsberg judge in the midst of the trial whether he would not like to be head of the FBI. And he continues to hold up Ehrlichman and Haldeman as models to the nation—“two of the finest public servants it has been my privilege to know.”

Nixon, in short, created the Nixon White House. “There was no independent sense of morality there,” said Hugh Sloan, who served in the Nixon White House for two years.” … If you worked for someone, he was God, and whatever the orders were, you did it . . . . It was all so narrow, so closed. . . . There emerged some kind of separate morality about things.” “Because of a certain atmosphere that had developed in my working at the White House,” said Jeb Stuart Magruder, “I was not as concerned about its illegality as I should have been.” “The White House is another world,” said John Dean. “Expediency is everything.” “No one who had been in the White House,” said Tom Charles Huston, “could help but feel he was in a state of siege.” “On my first or second day in the White House.” said Herbert Porter, “Dwight Chapin [the President’s appointments secretary] said to me, ‘One thing you should realize early on, we are practically an island here. That was the way the world was viewed.’” The “original sin,” Porter felt, was the “misuse” of young people “through the whole White House system. They were not criminals by birth or design. Left to their own devices, they wouldn’t engage in this sort of thing. Someone had to be telling them to do it.” Gordon Strachan told of his excitement at “being twenty-seven years old and walking into the White House and seeing the President”; but, when asked what word he had for other young men who wanted to come to Washington and enter the public service, he said grimly, “My advice would be to stay away.”

This is not the White House we have known—those of us, Democrats or Republicans, who served other Presidents in other years. Appointment to the White House of Roosevelt or Truman or Eisenhower or Kennedy or Johnson seemed the highest responsibility one could expect and therefore required higher standards of behavior than most of us had recognized before. And most of us look back at our White House experience, not with shame and incredulity, as the Nixon young men do, but as the most exhilarating time in our lives. Government, as Clark Clifford says, is a chameleon, taking its color from the character and personality of the President.

Moreover, Nixon’s responsibility for the White House ethos goes beyond strictly moral considerations. In the First Congress, Madison, arguing that the power to remove government officials must belong to the President, added, “We have in him the security for the good behavior of the officer.” This makes “the President responsible to the public for the conduct of the person he has nominated and appointed.” If the President suffers executive officials to perpetrate crimes or neglects to superintend their conduct so as to check excesses, he himself, Madison said, is subject to “the decisive engine of impeachment.”

II

The crisis of the presidency has led some critics to advocate a reconstruction of the institution itself. For a long time people have felt that the job was becoming too much for one man to handle. “Men of ordinary physique and discretion,” Woodrow Wilson wrote as long ago as 1908, “cannot be Presidents and live, if the strain be not somehow relieved. We shall be obliged always to be picking our chief magistrate from among wise and prudent athletes,—a small class.”

But what was seen until the late 1950s as too exhausting physically is now seen, after Vietnam and Watergate, as too dizzying psychologically. In 1968 Eugene McCarthy, the first liberal presidential aspirant in the century to run against the presidency, called for the depersonalization and decentralization of the office. The White House, he thought, should be turned into a museum. Instead of trying to lead the nation, the President should become “a kind of channel” for popular desires and aspirations. Watergate has made the point irresistible. “The office has become too complex and its reach too extended,” writes Barbara Tuchman, “to be trusted to the fallible judgment of any one individual.” “A man with poor judgment, an impetuous man, a sick man, a power-mad man,” adds Max Lerner, “each would be dangerous in the post. Even an able, sensitive man needs stronger safeguards around him than exist today.”

The result is a new wave of proposals to transform the presidency into a collegial institution. Mrs. Tuchman suggests a six-man directorate with a rotating chairman, each member to serve for a year, as in Switzerland. Lerner wants to give the President a Council of State, a body that he would be bound by law to consult and that, because half its members would be from Congress and some from the opposite party, would presumably give him independent advice. Both proposals were, in fact, considered and rejected at the Constitutional Convention.

Hamilton and Jefferson disagreed on many things, but they agreed that the convention had been right in deciding on a one-man presidency. A plural executive, Hamilton contended, if divided within itself, would lead the country into factionalism and anarchy and, if united, could lead it into tyranny. When power was placed in the hands of a group small enough to admit “of their interests and views being easily combined in a common enterprise, by an artful leader,” Hamilton thought, “it becomes more liable to abuse, and more dangerous when abused, than if it be lodged in the hands of one man, who, from the very circumstances of his being alone, will be more narrowly watched and more readily suspected.” With a single executive it was possible to fix accountability. But a directorate “would serve to destroy or would greatly diminish, the intended and necessary responsibility of the Chief Magistrate himself.”

Jefferson had favored a plural executive under the Articles of Confederation and as an American in Paris, he watched with sympathy the Directoire of the French Revolution. But these experiments left him no doubt that plurality was a mistake. As he later observed, if Washington’s Cabinet, in which he had served with Hamilton, had been a directorate, “the opposing wills would have balanced each other and produced a state of absolute inaction.” But Washington, after listening to both sides, acted on his own, providing the “regulating power which would keep the machine in steady movement.” History, moreover, furnished “as many examples of a single usurper arising out of a government by a plurality, as of temporary trusts of power in a single hand rendered permanent by usurpation.”

The question remains whether the world has changed enough in two centuries to make these objections obsolete. There is, of course, the burden-of-the-presidency argument. But is the presidential burden so much heavier than ever before? The scope of the national government has expanded beyond imagination, but so too have the facilities for presidential management. The only President who clearly died of overwork was Polk, and that was a long time ago. Hoover, who worked intensely and humorlessly as President, lived for more than thirty years after the White House; Truman, who worked intensely and gaily, lived for twenty. The contemporary President is really not all that overworked. Eisenhower managed more golf than most corporation officials or college presidents; Kennedy always seemed unhurried and relaxed; Nixon spends almost as much time in Florida and California as in Washington, or so it appears. Johnson’s former press secretary, George Reedy, has dealt with the myth of the presidential workload in terms that rejoice anyone who has ever served in the White House. “There is far less to the presidency, in terms of essential activity,” Reedy correctly says, “than meets the eye.” The President can fill his hours with as much motion as he desires but he also can delegate as much “work” as he desires. “A president moves through his days surrounded by literally hundreds of people whose relationship to him is that of a doting mother to a spoiled child. Whatever he wants is brought to him immediately—food, drink, helicopters, airplanes, people, in fact, everything but relief from his political problems.”

As for the moral and psychological weight of these political problems, this is real enough. All major presidential decisions are taken in conditions of what General Marshall, speaking of battle, used to call “chronic obscurity”—that is, on the basis of incomplete and probably inaccurate intelligence, with no sure knowledge where the enemy is or even where one’s own men are. This can be profoundly anguishing for reasonably sensitive Presidents, especially when decisions determine people’s livelihoods or end their lives. It was this, and not the workload, that did in Wilson and the second Roosevelt. But is the sheer moral weight of decision greater today than ever before? Greater for Johnson and Nixon than for Washington and Lincoln or Wilson or FDR? I doubt it very much.

If there is an argument for a plural executive, it is not the alleged burden of the presidency. The serious argument is simply to keep one man from wielding too much power. But here the points of Hamilton and Jefferson still have validity. The Council of Ten in Venice was surely as cruel as any doge. One wonders whether a six-man presidency would have prevented the war in Vietnam. It might well, however, have prevented the New Deal. The single-man presidency, with the right man as President, has its uses; and historically Americans have as often as not chosen the right man.

The idea of a Council of State has more plausibility. But it works better for foreign than for domestic policy. A prudent President is well advised to convoke ad hoc Councils of State on issues of war and peace. Kennedy added outsiders to his Executive Committee during the Cuban missile crisis; and it was an ad hoc Council of State in March, 1968, that persuaded Johnson to cease and desist in Vietnam. But, as an institutionalized body, with membership the ex officio perquisite of the senior leadership of House and Senate—that is, of the men in Congress who in the past have always been inclined to go along with Presidents—it could easily become simply one more weapon for a strong President. As Gouverneur Morris said at the Constitutional Convention, the President “by persuading his Council . . . to concur in his wrong measures would acquire their protection for them.”

Above all, both the plural executive and the Council of State are open to the objection that most concerned the Founding Fathers—the problem of fixing accountability. In the case of high crimes and misdemeanors, who, to put it bluntly, is to be impeached? The solution surely lies not in blurring responsibility for the actions of the executive but in making that responsibility categorical and in finding ways of holding Presidents to it.

III

The other change in the institution of the presidency under discussion runs in the opposite direction. The idea of a single six-year presidential term is obviously designed not to reduce but to increase the independence of the presidency. This idea naturally appeals to the imperial ethos. Lyndon Johnson advocated it; Nixon has commended it to his Commission on Federal Election Reform for particular study. What is more puzzling is that it also has the support of two eminent senators, both unsympathetic to the imperial presidency, Mike Mansfield of Montana and George Aiken of Vermont—support that gives it a hearing it would not otherwise have had.

It is not a new idea. Andrew Jackson recommended to Congress an amendment limiting Presidents to a single term of four to six years; Andrew Johnson did the same; the Confederate Constitution provided for a single six-year term. Mansfield and Aiken now press their version on the ground, as Mansfield says, that a six-year term would “place the Office of the Presidency in a position that transcends as much as possible partisan political considerations.” The amendment, says Aiken, “would allow a President to devote himself entirely to the problems of the Nation and would free him from the millstone of partisan politics.”

This argument has a certain old-fashioned good-government plausibility. How nice it would be if Presidents could be liberated from politics for six years and set free to do only what is best for the country! But the argument assumes that Presidents know better than anyone else what is best for the country and that the democratic process is an obstacle to wise decisions. It assumes that Presidents are so generally right, and the people so generally wrong that the President has to be protected against political pressures. It is, in short, a profoundly antidemocratic position. It is also profoundly unrealistic to think that any constitutional amendment could transport a President to some higher and more immaculate realm and still leave the United States a democracy. As Thomas Corcoran told the Senate Judiciary Committee during hearings on the Mansfield-Aiken amendment, “It is impossible to take politics out of politics.”

But, even if it were possible to take the presidency out of politics, is there reason to suppose this desirable? The electorate often knows things that Presidents do not know; and the nation has already paid a considerable price for presidential isolation and ignorance. Few things are more likely to make Presidents sensitive to public opinion than worrying about their own political future. Moreover, if public opinion is at times a baneful influence, what else is democracy all about? The need to persuade the nation of the soundness of a proposed policy is the heart of democracy. “A President immunized from political considerations.” Clark Clifford told the Senate Judiciary Committee, “is a President who need not listen to the people, respond to majority sentiment, or pay attention to views that may be diverse, intense and perhaps at variance with his own.”

The Mansfield-Aiken amendment expresses distrust of the democratic process in still another way—by its bar against re-eligibility. If anything is of the essence of democracy, it is surely that the voters should have an unconstrained choice of their leaders. “I can see no propriety,” George Washington wrote the year after the adoption of the Constitution, “in precluding ourselves from the service of any man, who on some great emergency shall be deemed universally most capable of serving the public.”

IV

Oddly, the crisis of the imperial presidency has not elicited much support for what at other times has been a favored theory of constitutional reform: movement in the direction of the British parliamentary system. This is particularly odd because, whatever the general balance of advantage between the parliamentary and presidential modes, the parliamentary system has one feature the presidential system badly needs now—the requirement that the head of government be compelled at regular intervals to explain and defend his policies in face-to-face sessions with the political opposition. Few devices, it would seem, are better calculated both to break down the real isolation of the latter-day presidency and to dispel the spurious reverence that has come to envelop the office.

In a diminished version, applying only to members of the Cabinet, the idea is nearly as old as the republic itself. The proposal that Cabinet members should go on to the floor of Congress to answer questions and take part in debate, “far from raising any constitutional difficulties,” as F. S. Corwin once observed, “has the countenance of early practice under the Constitution.” The Confederate Constitution authorized Congress to grant the head of each executive department “a seat upon the floor of either House, with the privilege of discussing any measures appertaining to his department,” and Congressman George H. Pendleton of Ohio, with the support of Congressman James A. Garfield, argued for a similar proposal in the Union Congress in 1864. In his last annual message, President William Howard Taft suggested that Cabinet members be given access to the floor in order, as he later put it, “to introduce measures, to advocate their passage, to answer questions, and to enter into debate as if they were members, without of course the right to vote … The time lost in Congress over useless discussion of issues that might be disposed of by a single statement from the head of a department, no one can appreciate unless he has filled such a place.”

In the meantime, the young Woodrow Wilson carried the idea a good deal further toward the British model, arguing that Cabinet members should not just sit voteless in Congress but should be actually chosen “from the ranks of the legislative majority.” Instead of the chaotic and irresponsible system of government by congressional committees, the republic would then have Cabinet government and ministerial responsibility. Though Wilson did not renew this specific proposal in later years, it very likely lingered in the back of his mind. On the eve of his first inauguration he noted that the position of the presidency was “quite abnormal, and must lead eventually to something very different.” “Sooner or later,” the President must be made “answerable to opinion in a somewhat more informal and intimate fashion—answerable, it may be, to the Houses whom he seeks to lead, either personally or through a cabinet, as well as to the people for whom they speak. But that is a matter to be worked out.”

Wilson never found time to work it out. Today there appears to be little interest in reforms that squint at parliamentarianism. This may be in part because the parliamentary regimes best known in America—the British and French—have themselves moved in the direction of prime-ministerial or presidential government and offer few guarantees against the Vietnam-Watergate effect.

V

The problem of reining in the runaway presidency centers a good deal more at the moment on substantive than on structural solutions. Congress, in other words, has decided it can best restrain the presidency by enacting specific legislation in the conspicuous fields of presidential abuse. The main author of this comprehensive congressional attack on presidential supremacy, well before he assumed the chairmanship of the Senate Select Committee investigating Watergate, has been Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina.

The republic owes a great deal to Sam Ervin. No one for a long time has done so much to educate the American people in the meaning and majesty of the Constitution (though his Constitution seems to stop with the tell amendments adopted in 1791: at least he does not show the same fervor about the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments as he does about the First and Fourth). For most Americans the Constitution has become a hazy document, cited like the Bible on ceremonial occasions but forgotten in the daily transactions of life. For Ervin the Constitution, like the Bible, is superbly alive and fresh. He quotes it as if it had been written the day before; the Founding Fathers seem his contemporaries; it is almost as if he has ambled over from the Convention at Philadelphia. He is a true believer who endows his faith with abundant charm, decency, sagacity, and toughness. The old-fashioned Constitution—“the very finest document ever to come from the mind of men”–could have no more fitting champion in the battle against the imperial presidency.

But Ervin is concerned with more than the vindication of the Constitution. His larger design is to establish a new balance of constitutional power. Congress itself, Ervin thinks, has negligently become “the chief aggrandizer of the Executive.” The restoration of the Constitution, he believes, requires the systematic recovery by Congress of powers appropriated by the presidency. The bills designed to constrain presidential war powers are, in his view, a confused and sloppy application of this strategy; he has little use for them. His own approach, direct and unequivocal, is expressed in the bill in which he proposes to give Congress absolute authority to veto executive agreements within sixty days. Congress never had, or even seriously sought, such authority before. While the provocation is real enough, the bill, if enacted, would give Congress unprecedented control over the presidential conduct of foreign affairs.

A leading item on Ervin’s domestic agenda is executive privilege. This question has been historically one of conflicting and unresolved constitutional claims. In the nineteenth century, while insisting on a general congressional right to executive information, Congress acknowledged a right, or at least a power, of presidential denial in specific areas. It acquiesced in these reservations because they seemed reasonable and because responsible opinion saw them as reasonable. But what Congress saw as an expression of constitutional comity, Presidents in the later twentieth century—Nixon above all—have come to see as their inherent and unreviewable constitutional right.

Ervin, in response, has introduced a bill requiring members of the executive branch summoned by a committee of Congress to appear in person, even if the intend to claim executive privilege. Only a personal letter from the President could warrant the claim: and the bill gives the committee the power to decide whether the presidential plea is justified, In the words of Senator William Fulbright, it places “the final responsibility for judging the validity of a claim of executive privilege in the Congress, where it belongs.”

A presidential thesis in violation of the traditional comity between the two branches has thus produced a congressional answer that would itself do away with what has been not only a historic but a healthy ambiguity. For one hundred and eighty years the arbiter in this question has been neither Congress nor the President nor the courts but the political context and process, with responsible opinion considering each case more or less on merit and turning against whichever side appears to be overreaching itself. The system is not tidy, but it encourages a measure of restraint on both sides and has avoided a constitutional showdown. Now absolute presidential claims have provoked an absolute congressional response. Would this really be an improvement? Would Ervin and Fulbright themselves twenty years earlier have wanted to give Joe McCarthy and his committee “the final responsibility” to judge whether executive testimony could be properly withheld?

Next on the Ervin agenda stands the restoration of congressional control over something it has thought it had anyway—the power of the purse. This means a solution of the problem of presidential impoundment. Impoundment existed before Nixon, but no previous President used it to overturn statutes and abolish programs against congressional will. For Nixon, impoundment is a means of taking from Congress the determination of national priorities.

The courts have been more willing to grasp the nettle of impoundment than they were, at least at the start, in the case of executive privilege. In decision after decision this year, judges have declared one aspect after another of the impoundment policy illegal. No judge has accepted Nixon’s claim that he has a “constitutional right” not to spend money voted by Congress. One judge calls his use of impoundment “a flagrant abuse of executive discretion.” “It is not within the discretion of the Executive,” says another, “to refuse to execute laws passed by Congress but with which the Executive presently disagrees.” The decisions are, however, as they should be, constructions of specific statutes and stop short of proposing a general solution to the impoundment controversy.

Though the courts have rallied splendidly, it is not really very satisfactory to have to sue the executive branch in every case in order to make it carry out programs duly enacted by Congress. But Congress itself has found it hard to make a stand on the Constitution. For Nixon has changed the issue with some success from a constitutional to a budgetary question. Impoundment, in other words, is alleged as the only answer a fiscally responsible President can make to insensate congressional extravagance. Sam Ervin derides this proposition. “Congress,” he says, “is not composed of wild-eyed spenders, nor is the President the embattled crusader against wasteful spending that he would have you believe.” The figures bear Ervin out. Congress, for example, cut more than $20 billion from Administration appropriation requests in Nixon’s first term. Congress and the presidency roughly agree on the amount of money government should spend but disagree, as Ervin puts it, “over spending priorities and [the President’s] authority to pick and choose what programs he will fund.” Impoundment, says Ervin, has to do not with the budget but with the separation of powers.

It is a political fact, fully recognized by Ervin, that anti-impoundment legislation will have to be accompanied by new evidences of congressional self-control in spending. Ervin is personally a budget-balancer anyway. So his impoundment bill includes a spending ceiling. The bill, as passed by the Senate in 1973, also has certain eccentricities for a constitutional fundamentalist. After a clear statement in Section 1 that impoundment is unconstitutional, subsequent sections say that nevertheless the President is authorized to commit this unconstitutional act for periods up to seventy days. Thereafter impoundments not covered by the anti-deficiency acts (which permit the executive to impound funds not required to achieve the purpose of a statute) must cease unless Congress specifically approves them by concurrent resolution. The House, on the other hand, is quite willing to let impoundments stand unless specifically disapproved by one house of Congress. Both bills legitimize impoundment; but, where the House would place the burden on Congress in each case to stop impoundment, Ervin would place the burden on the President in each case to justify impoundment.

VI

In one area after another, with the concealed passion and will of a deceptively relaxed personality, Ervin is moving to restore the balance of the Constitution by cutting the presidency down to constitutional size. However, his is the Constitution not of Abraham Lincoln but of ex parte Milligan. “What the framers intended,” he says, “was that the President … should be merely the executor of a power of decision that rests elsewhere; that is, in the Congress. This was the balance of power between the President and Congress intended by the Constitution.” The “ultimate power,” Ervin says, is “legislative.”

It is hard to know how literally to take the Ervin scheme. If it sounds at times like an effort to replace presidential government by congressional government, it must be remembered that the Ervin proposals have been provoked by an attempt to alter the nature of the system. Ervin and his colleagues are fighting to protect Congress from the plebiscitary presidency, not to frustrate the leadership of a President who recognizes his accountability to Congress and the Constitution. Yet, if taken literally, the Ervin scheme is a scheme of presidential subordination. Where presidential abuse of particular powers has harmed the country, those powers are now to be vested in Congress. Pursued to the end, the Ervin scheme could produce a national polity which would be almost as overbalanced in the direction of congressional supremacy as the Nixon scheme is in the direction of presidential supremacy.

The Ervin counterattack thus runs the risk of creating a generation of weak Presidents in an age when the turbulence of race, poverty, inflation, crime, and urban decay is straining the delicate bonds of national cohesion and demanding, quite as much as in the 1930s, a strong domestic presidency to hold the country together. For Sam Ervin is of the pure Jeffersonian school, like the old Tertium Quids who felt that Jefferson and Madison, in building up the presidency and seeing the national government as an instrument of the general welfare, had deserted the true faith.

The pure Jeffersonian doctrine was a witness rather than a policy, which is why Jefferson and Madison themselves abandoned it. The pure Jeffersonian idea of decentralized power receded in the course of American history because local government simply did not offer the means to attain Jeffersonian ends. In practice, pure Jeffersonianism meant a system under which the strongest local interests, whether planters, landlords, merchants, bankers, or industrialists, consolidated their control and oppressed the rest; it meant all power to the neighborhood oligarchs. Theodore Roosevelt explained at the start of the twentieth century why Hamiltonian means had become necessary to achieve Jeffersonian ends, how national authority was the only effective means of correcting injustice in a national society. “If Jefferson were living in our day,” said Wilson in 1912, “he would see what we see: that the individual is caught in a great confused nexus of complicated circumstances, that . . . without the watchful interference and of the government there can be no fair play.” And, for the first Roosevelt and for Wilson, as for their joint heir, the second Roosevelt, national authority was embodied in the presidency.

This has not been a bad thing for the republic. It is presidential leadership, after all, that brought the country into the twentieth century, that civilized American industry, secured the rights of labor organization, defended the livelihood of the farmer. It is presidential leadership that has protected the Bill of Rights against local vigilantism and natural resources against local greed. It is presidential leadership, spurred on by the Supreme Court, that has sought to vindicate racial justice against local bigotry. Congress would have done few of these things on its own; local government even fewer. It. would be a mistake to cripple the presidency at home because of presidential excesses abroad. History has shown the presidency to be the most effective instrumentality of government for justice and progress. Even Calvin Coolidge, hardly one of the more assertive of Presidents, said, “It is because in their hours of timidity the Congress becomes subservient to the importunities of organized minorities that the President comes more and more to stand as the champion of the rights of the whole country.”

The scheme of presidential subordination can easily be pressed to the point of national folly. But it is important to contend not for a strong presidency in general, but for a strong presidency within the Constitution. The presidency deserves to be defended on serious and not on stupid points. Watergate has produced flurries of near hysteria about the life expectancy of the institution. Thus Charles L. Black, Jr., Luce Professor of Jurisprudence at the Yale Law School, argues that, if Nixon turned over his White House tapes to Congress or the courts, it would mean the “danger of degrading or even destroying the Presidency” and constitute a betrayal of his “successors for all time to come.” The republic, Black says, cannot even risk diluting the “symbolism” of the office lest that disturb “in the most dangerous way the balance of the best government yet devised on earth”; and it almost seems that he would rather suppress the truth than jeopardize the symbolism.

Executive privilege is not the issue. No Presidents cherished the presidency more than, say, Jackson or Polk; but both readily conceded to Congress the right in cases of malversation to penetrate into the most secret recesses of the executive department. Nor, in the longer run, does either Ervin’s hope of presidential subordination or Black’s fantasy of presidential collapse have real substance. For the presidency, though its wings can be clipped for a time, is an exceedingly tough institution. Its primacy is founded in the necessities the American political order. It has endured many challenges and survived many vicissitudes. It is nonsense to suppose that its fate as an institution is bound up with the fate of the particular man who happens to be President at any given time. In the end power in the American order is bound to flow back to the presidency.

Congress has a marvelous, if generally unfulfilled, capacity for oversight, for advice, for constraint, for chastening the presidency and informing the people. When it really wants to say no to a president, it has ample means of doing so; and in due course the President will have no choice but to acquiesce. But it is inherently incapable of conducting government and providing national leadership. Its fragmentation, its chronic fear of responsibility, its habitual dependence on the executive for ideas, information, and favors—this is life insurance for the presidency.

Both Nixon and Ervin are wrong in supposing that the matter can be settled by shifting the balance of power in a decisive way to one branch or the other. The answer lies rather in preserving fluidity and re-establishing comity. Indeed, for most people—here Ervin is a distinguished exception—the constitutional and institutional issues are make-believe. It is largely a matter, as Averell Harriman says, “of whose ox is getting gored: who is in or out of power, and what actions either side may want.” When Nixon was in the opposition, there was no more earnest critic of presidential presumption. Each side dresses its arguments in grand constitutional and institutional terms, but their contention is like that of the two drunken men described long ago by Lincoln who got into a fight with their greatcoats on until each fought himself out of his own coat and into the coat of the other.

VII

What is required is, in Herbert Wechsler’s case, a set of neutral principles—principles, that is, that are not shaped in response to a particular situation but work all the time, transcending any particular result involved. The supreme neutral principle, as vital in domestic policy as in foreign policy, is that all great decisions of the government must be shared decisions. The subsidiary principle is that if the presidency tries to transform what the Constitution sees as concurrent into exclusive authority, it must be stopped; and if Congress tries to transform concurrent into exclusive authority, it must be stopped too. If either the presidency or Congress turns against the complex balance of constitutional powers that has left room over many generations for mutual accommodation, then the ensuing collision will harm both branches of government and the republic as well. Even together, Congress and the presidency are by no means infallible; but their decisions, wise or foolish, at least meet the standards of democracy. And, taken together, the decisions are more likely to be wise than foolish.

All Presidents affect a belief in common counsel, but most after a time prefer to make other arrangements. Still, the idea is right, and the process of accountability has to begin inside the President himself. A constitutional President can do many things, but he has to believe in the discipline of consent. It is not enough that he personally thinks the country is in trouble and genuinely believes he alone knows how to save it. In all but the most extreme cases, action has to be accompanied by public explanation and tested by public acceptance. A constitutional President has to be aware of what Whitman called “the never-ending audacity of elected persons” and has to understand the legitimacy of challenges to his own judgment and authority. He has to be sensitive directly to the diversity of concern and conviction in the nation, sensitive prospectively to the verdict of history, sensitive always to the decent respect pledged in the Declaration of Independence to the opinions of mankind.

Yet Presidents chosen as open and modest men are not sure to remain so amid the intoxications of the office; and the office has grown steadily more intoxicating in recent years. A wise President, having read George Reedy and observed the fates of Johnson and Nixon, will take care to provide himself, while there still is time, with antidotes to intoxication. Presidents in the last quarter of the twentieth century might, as a beginning, plan to rehabilitate (I use the word in almost the Soviet sense) the executive branch of government. This does not mean the capitulation of the presidency to the permanent government; nor should anyone forget that it was the unresponsiveness of the permanent government that gave rise to the aggressive White House of the twentieth century. But it does mean a reduction in the size and power of the White House staff and the restoration of the access and prestige of the executive departments. The President will always need a small and alert personal staff to serve as his eyes and ears and one lobe of his brain, but he must avoid a vast and possessive staff ambitious to make all the decisions of government. Above all, he must not make himself the prisoner of a single information system. No sensible President will give one man control of all the channels of communication; any man sufficiently wise to exercise such control properly ought to be President himself.

As for the Cabinet, while no President in American history has found it a very satisfactory instrument of government, it has served Presidents best when it has contained men strong and independent in their own right, strong enough to make the permanent government responsive to presidential policy and independent enough to carry honest dissents into the Oval Office. Franklin Roosevelt, who is fashionably regarded these days as the cause of it all, is really a model of how a strong President can operate within the constitutional order. While no President wants to create the impression that his Administration is out of control, FDR showed how a masterful President could maintain the most divergent range of contacts, surround himself with the most articulate and positive colleagues, and use debate within the executive branch as a means of clarifying issues and trying out people and policies. Or perhaps FDR is in a way the cause of it all, because he alone had the vitality, flair, and cunning to be clearly on top without repressing everything underneath. In a joke that Henry Wallace, not usually a humorous man, told in my hearing in 1943, FDR could keep all the balls in the air without losing his own. Some of his successors tried to imitate his mastery without understanding the sources of his strength.

But not every President is an FDR, and FDR himself, though his better instincts generally won out in the end, was a flawed, willful, and, with time, increasingly arbitrary man. When Presidents begin to succumb to delusions of grandeur, when the checks and balances inside themselves stop operating, external checks and balances may well become necessary to save the republic. The nature of an activist President in any case, in Samuel Lubell's phrase, is to run with the ball until he is tackled. As conditions abroad and at home have nourished the imperial presidency, tacklers have had to be more than usually sturdy and intrepid.

How to make external checks effective? Congress can tie the presidency down by a thousand small legal strings; but, like Gulliver, the President can always break loose. The effective means of controlling the presidency lie not in law but in politics. For the American President rules by influence; and the withdrawal of consent, by Congress, by the press, by public opinion, can bring any President down. The great Presidents have understood this. The President, said Andrew Jackson, must be “accountable at the bar of public opinion for every act of his Administration.” “I have a very definite philosophy about the Presidency,” said Theodore Roosevelt. “I think it should be a very powerful office, and I think the President should be a very strong man who uses without hesitation every power that the position yields; but because of this fact I believe that he should be sharply watched by the people [and] held to a strict accountability by them.”

Holding a President to strict accountability requires, first of all, a new attitude on the part of the American people toward their Presidents, or rather a return to the more skeptical attitude of earlier times: it requires, specifically, a decline in reverence. An insistent theme in Nixon's public discourse is the necessity of maintaining due respect for the presidency. The possibility that such respect might be achieved simply by being a good President evidently does not reassure him. He is preoccupied with “respect for the office” as an entity in itself. Can one imagine Washington or Lincoln or the Roosevelts or Truman or Kennedy going on in public, as Nixon repeatedly does, about how important it is to do this or that in order to maintain “respect for the office”? But the age of the imperial presidency has produced the idea that run-of-the-mill politicians, brought by fortuity to the White House, must be treated thereafter as if they have become superior and perhaps godlike beings.

The Nixon theoreticians even try to transform reverence into an ideology, propagating' the doctrine, rather novel in the United States, that institutions 'of authority are entitled to respect per se, whether or not they have done anything to earn respect. If authority is denied respect, the syllogism ran, the whole social order will be in danger. “Your task, then, is clear,” Pat Moynihan charged his President in 1969: “To restore the authority of American institutions.” But should institutions expect obedience that they do not, on their record of performance, deserve? To this question the Nixon ideologues apparently answer yes. An older American tradition would say no, incredulous that anyone would see this as a question. In that spirit I would argue that what the country needs today is a little serious disrespect for the office of the presidency; a refusal to give any more weight to a President's words than the intelligence of the utterance, if spoken by anyone else, would command; an understanding of the point made so aptly by Montaigne: “Sits he on never so high a throne, a man still sits on his bottom.”

But what if men not open and modest, even the start, but from the start ambitious of power and contemptuous of law, reach the place once occupied by Washington and Lincoln? What if neither personal character, nor the play of politics, nor the Constitution itself avail to hold a President to strict accountability? In the end, the way to control the presidency may have to be not in many little ways but in one large way. In the end, there remains, as Madison said, the decisive engine of impeachment.

VIII

This is, of course, the instrument provided by the Constitution. But it is an exceedingly blunt instrument. Only once has a President been impeached, and there is no great national desire to go through the experience again. Yet, for the first time in a century, Americans in the 1970s have to think hard about impeachment, which means that, because most of us flinch from the prospect, we begin to think hard about alternatives to impeachment.

One alternative is the censure of the President by the Congress. That was tried once in American history—in 1834, when the Senate censured Andrew Jackson on the ground that, in removing the government deposits from the Second Bank of the United States, he had “assumed upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both.” Jackson's “protest” to the Senate was eloquent and conclusive. The Senate resolution, he said, charged him with having committed a “high crime.” It was therefore “in substance an impeachment of the President.” If Congress really meant this, Jackson said, let it be serious about it: let the House impeach him and the Senate try him. Jackson was plainly right. The slap-on-the-wrist approach to presidential delinquency makes little sense, constitutional or otherwise. There is no halfway house in censure. If a President has committed high crimes and misdemeanors, he should not stay in office. This does not mean, of course, that a fainthearted Congress may not pass a resolution of censure and claim to have done its duty. But, unless the terms of the resolution make it clear why the President is merely censurable and not impeachable, the action is a cop-out and a betrayal of Congress' constitutional responsibility.

Are there other halfway houses? Another proposal seems worth consideration: that is, the removal of an offending President by some means short of impeachment. A resolution calling on the President to resign and passed by an overwhelming vote in each house could have a powerful effect on a President who cares about the Constitution and the country. If either the President or the Vice President then resigned, the President, old or new, could, under the Twenty-fifth Amendment, nominate a new Vice President, who would take office upon confirmation by both houses of Congress. “Admirable,” said Cardinal Fleury after he read the Abbé de Saint-Pierre's Projet de Paix Perpétuelle, “save for one omission: I find no provision for sending missionaries to convert the hearts of princes.” Alas, Presidents who succeed in provoking a long-suffering Congress into a resolution calling for their resignation are not likely to be deeply moved by congressional disapproval nor inclined to cooperate in their own liquidation.

If Presidents will not resign of their own volition, can they be forced out without the personal and national ordeal of impeachment and conviction?

A proposal advanced in various forms by leading members of the House of Representatives this year contemplates giving Congress authority by constitutional amendment to call for a new presidential election when it finds that the President can no longer perform the functions of his office (Representative Bingham) or that the President has violated the Constitution (Representatives Edith Green and Morris Udall).

The possibility of dissolution and new elections at times of hopeless stalemate or blasted confidence has serious appeal. Dissolution would give a rigid electoral system flexibility and responsiveness. It would permit, in Bagehot's phrase, the timely replacement of the pilot of the calm by the pilot of the storm. It would remind intractable Congresses that they cannot block Presidents with immunity, as it would remind high-flying Presidents that there are other ways of being shot down besides impeachment. But my instinct is somehow against it. One congressman observes of the Green-Udall amendment that it “would, in effect, take one-half of the parliamentary process and not the entire parliamentary process.” This is certainly the direction and logic of dissolution. The result might well be to alter the balance of the Constitution in unforeseeable and perilous ways. It might, in particular, strengthen the movement against the separation of powers and toward a plebiscitary presidency. “The republican principle,” said the 71st Federalist, “demands that the deliberate sense of the community should govern the conduct of those to whom they intrust the management of their affairs: but it does not require an unqualified complaisance to every sudden breeze of passion, or to every transient impulse which the people may receive from the arts of men, who flatter their prejudices to betray their interests.”

I think that the possibility of inserting dissolution into the American system is worth careful examination. But digging into the foundations of the state, as Burke said, is always a dangerous adventure.

IX

Impeachment, on the other hand, is part of the original foundation of the American state. The Founding Fathers placed the blunt instrument in the Constitution with the expectation that it would be used, and used most especially against Presidents. “No point is of more importance,” George Mason told the Convention, “than that the right of impeachment should be continued. Shall any man be above Justice? Above all shall that man be above it, who [as President] can commit the most extensive injustice?” Benjamin Franklin pointed out that, if there were no provision for impeachment, the only recourse would be assassination, in which case a President would be “not only deprived of his life but of the opportunity of vindicating his character.” Corruption or loss of capacity in a President, said Madison, was “within the compass of probable events . . . . Either of them might be fatal to the Republic.”

The genius of impeachment lies in the fact that it can punish the man without punishing the office. For, in the presidency, as elsewhere, power is ambiguous: the power, to do good means also the power to do harm, the power to serve the republic also the power to demean and defile it. The trick is to preserve presidential power but to deter Presidents from abusing that power. Shall any man be above justice? George Mason asked. Obviously not; not even a President of the United States. But bringing Presidents to justice is not all, that simple.

History has turned impeachment into a weapon of last resort—more so probably than the Founding Fathers anticipated; Still, it is possible to exaggerate its impact on the country. It took less than three months to impeach and try Andrew Johnson, and the nation—in a favorite apprehension of 1868 as well as of 1973—was not torn apart in the process. Three months of surgery might be better than three years of paralysis. Yet impeachment presents legal as well as political problems. There is broad agreement, among scholars at least, on doctrine. Impeachment is a proceeding of a political nature, by no means restricted to indictable crimes. On the other hand, it plainly is not to be applied to cases of honest disagreement over national policy or over constitutional interpretation, especially when a President refuses to obey a law that he believes strikes directly at the presidential prerogative. Impeachment is to be reserved, in Mason's phrase at the Constitutional Convention, for “great and dangerous offenses.”

The Senate, in trying impeachment cases, is better equipped to be the judge of the law than of the facts. When Andrew Johnson was impeached, there had been no dispute about the fact that he had removed Stanton. When Andrew Jackson was censured, there had been no dispute about the fact that he had removed the deposits. The issue was not whether they had done something but whether what they had done constituted a transgression of the laws and the Constitution: But in the Nixon case the facts themselves remain at issue—the facts, that is, of presidential complicity—and the effort of a hundred senators to determine those facts might well lead to chaos. The record here may be one of negligence, irresponsibility, and even deception, but it is not necessarily one of knowing violation of the Constitution or of knowing involvement in. the obstruction of justice. While impeachment is in the Constitution to be used, there is no point in lowering the threshold so that it will be used casually. All this argues for the determination of facts before the consideration of impeachment. There are two obvious ways to determine the facts. One is through the House of Representatives, which has the sole power to initiate impeachment. The House could, for example, instruct the Judiciary Committee to ascertain whether there were grounds for impeachment, or it could establish a select committee to conduct such an inquiry. The other road is through the courts. If the Special Prosecutor establishes incriminating facts, these can serve as the basis for impeachment.

But what if a President himself withholds evidence—for example, Nixon's tapes—deemed essential to the ascertainment of facts? If a President says “the time has come to turn Watergate over to the courts, where the questions of guilt and innocence belong,” and then denies the courts the evidence they need to decide on innocence or guilt, what recourse remains to the republic except impeachment? Apart from the courts, President Polk said quite explicitly that the House, if it were looking into impeachment, could command testimony and papers, public and private official or unofficial, of every agent of the government. If a President declines for whatever reason to yield material evidence in his possession, whether to the courts or to the House, this itself might provide clear grounds for impeachment.

All these things are obscure in the early autumn of 1973. It is possible that Nixon may conclude that the Watergate problems are not after all (as he told the Prime Minister of Japan) “murky, small, unimportant, vicious little things,” but are, rather, evidence of a profound and grievous imbalance between the presidency and the Constitution. Perhaps he may, by an honest display of candor and contrition, regain a measure of popular confidence, re-establish constitutional comity and recover presidential effectiveness. But full recovery seems unlikely unless the President himself recognizes why his presidency has fallen into such difficulties. Nixon's continued invocation, after Watergate, of national security as the excuse for presidential excess, his defense to the end of unreviewable executive privilege, his defiant assertion that, if he had it to do over again, he would still deceive Congress and the people about the secret air war in Cambodia—such unrepentant reactions suggest that he still has no clue as to what his trouble was, still fails to understand that the sickness of his presidency is caused not by the overzealousness of his friends or by the malice of his enemies, but by the expansion and abuse of presidential power itself.

X

For the issue is more than whether Congress and the people wish to deal with the particular iniquities of the Nixon Administration. It is whether they wish to rein in the runaway presidency. Nixon's presidency is not an aberration but a culmination. It carries to reckless extremes a compulsion toward presidential power rising out of deep-running changes in the foundations of society. In a time of the acceleration of history and the decay of traditional institutions and values, a strong presidency is both a greater necessity than ever before and a greater risk—necessary to hold a spinning and distracted society together, necessary to make the separation of powers work, risky because of the awful temptation held out to override the separation of powers and burst the bonds of the Constitution. The nation requires both a strong presidency for leadership and the separation of powers for liberty. It may well be that, if continuing structural compulsions are likely to propel future Presidents in the direction of government by decree, the rehabilitation of impeachment Will be essential to contain the presidency and preserve the Constitution.

Watergate is potentially the best thing to have happened to the presidency in a long time. If the trails are followed to their end, many, many years will pass before another White House staff dares take the liberties with the Constitution and the laws the Nixon White House has taken. If the nation wants to work its way back to a constitutional presidency, there is only one way to begin. That is by showing Presidents that, when their closest associates place themselves above the law and the Constitution, such transgressions will be not forgiven or forgotten for the sake of the presidency, but exposed and punished for the sake of the presidency.

If the Nixon White House escapes the legal consequences of its illegal behavior, why will future Presidents and their associates not suppose themselves entitled to do what the Nixon White House has done? Only condign punishment will restore popular faith in the presidency and deter future Presidents from illegal conduct—so long, at least, as Watergate remains a vivid memory. Corruption appears to visit the White House in fifty-year cycles. This suggests that exposure and retribution inoculate the presidency against its latent criminal impulses for about half a century. Around the year 2023 the American people will be well advised to go on the alert and start nailing down everything in sight.

A constitutional presidency, as the great Presidents have shown, can be a very strong presidency indeed. But what keeps a strong President constitutional, in addition to checks and balances incorporated within his own breast, is the vigilance of the people. The Constitution cannot hold the nation to ideals it is determined to betray. The reinvigoration of the written checks in the American Constitution depends on the re-invigoration of the unwritten checks in American society. The great institutions—Congress, the courts, the executive establishment, the press, the universities, public opinion—have to reclaim their own dignity and meet their own responsibilities. As Madison said long ago, the country cannot trust to “parchment barriers” to halt the encroaching spirit of power. In the end, the Constitution will live only if it embodies the spirit of the American people.

“There is no week nor day nor hour,” wrote Walt Whitman, “when tyranny may not enter upon this country, if the people lose their supreme confidence in themselves,—and lose their roughness and spirit of defiance—Tyranny may always enter—there is no charm, no bar against it—the only bar against it is a large resolute breed of men.”