The Guardian is today publishing a list of 34,361 people who have lost their lives trying to get into Europe over the past 25 years. Many are just anonymous entries, but our reporters have investigated a few cases to put faces and stories to the victims.

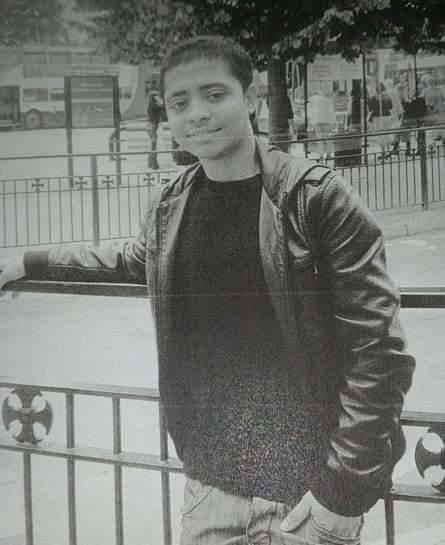

Rubel Ahmed

Born: Bangladesh, 1988.

Died: UK, 2014.

Rubel Ahmed only came to Britain out of curiosity, on a short-term working holiday visa. The oldest sibling from a poor family from Sylhet in Bangladesh, he felt keenly the responsibility on the firstborn to earn and provide for younger siblings. He started work as a chef.

He was so good at his job that different restaurants asked him to work for them, promising to sponsor him. Rubel had started sending money home, to turn the family shack in Shangiray into a brick house. He decided to stay on.

He applied for leave to remain in the UK. But this application was refused. He was detained under immigration powers on 21 July 2014 and taken to Morton Hall, the immigration removal centre in Lincolnshire that holds people subject to deportation orders. He was devastated when the Home Office informed him on 29 August that he would be removed to Bangladesh on 8 September.

“When he was initially detained in Morton Hall he thought he would get bail and be released after a week or so,” said a cousin, Ajmal Ali. “But when the release didn’t happen I think he lost hope. He couldn’t understand why he was locked up and treated like a criminal when he had committed no crime.”

Ahmed hanged himself in Morton Hall on 5 September 2014. He is one of more than 400 migrants and refugees on the List who have taken their own lives.

Quick GuideWhat is the List?

Show

What is the List?

Since 1993, activists at the network United for Intercultural Action have made a record of every reported instance in which someone has died trying to migrate into Europe. In all, 61 deaths were recorded in 1993; 3,915 were recorded in 2017.

What sources did they use?

The small team, based in the Netherlands, drew on reports in the local, national and international press, as well as NGO records. Though the vast majority of people died during en route for Europe – most of them at sea - the List also points out that hundreds died in custody, and hundreds more took their own lives. Most deaths recorded on the List are anonymous.

How many deaths have been recorded?

As of 5 May 2018, the figure stood at 34,361. But activists acknowledge that the List is neither definitive nor comprehensive. The real number is likely to be far higher, as many thousands of people will have died without trace during sea and land journeys over the years.

Why is the Guardian involved?

With work on the Windrush scandal and the award-winning New Arrivals series, the Guardian has demonstrated its commitment to exposing the social injustice faced by refugees and migrants. On Wednesday June 20, the Guardian becomes the first English-language daily to publish the List in full. It is also available as a PDF download on our website. This edition of The List is produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London and Liverpool Biennial.

Both the inquest into Ahmed’s death and the investigation into it by the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman were critical of procedures before his death.

The coroner said that there had been inadequate communication between officials, and the inquest jury found that removal directions contributed to and caused him to hang himself. They came to an open conclusion about his death. Ahmed’s family expressed concern about the lock-in regime at the centre – detainees were locked in for most of the evening as well as overnight. Ahmed’s family said that if Ahmed had been able to speak to other detainees in the hours before he took his life his death may have been prevented.

“Although his death happened a few years ago the impact on us, his family, of losing him, hasn’t really got any easier,” Ajmal Ali said.

Alan Kurdi

Born: Syria, 2012.

Died: Turkey, 2015.

The vast majority of refugees and migrants who die in their quest to seek a new life in Europe do so in wretched anonymity. But occasionally there is a case that cuts through, shakes public opinion and even changes policy.

Alan Kurdi was found on a Turkish beach three years ago. The image of the Syrian toddler lying face down in the surf sickened millions of Europeans, and prompted softer, more welcoming approaches to refugees in Germany, Britain and elsewhere.

Kurdi was from Kobani, a border town in northern Syria that for months was the epicentre of fighting between Islamic State and Kurdish forces. Syria was already at war when he was born in 2012. The family lived in a single unheated room with a hole in the floor for a toilet.

His father decided to move his wife and two children to Turkey, but subsequently decided to try to get to Canada, where Alan’s aunt Tima lives. The dinghy they travelled in to try to get from Bodrum to the Greek island of Kos quickly sank. It was built for eight people but there were 16 inside as it was launched for the short by dangerous passage from the Turkish coast to Kos. The lifejackets they were wearing were said to be either fake or ineffective.

Alan’s brother, Galip, and mother, Rehanna, also drowned. Abdullah survived. He and Tima have since established the Galip and Alan Kurdi Foundation to help children whose lives have been ruined by war.

Almost 10,000 people have died trying to get into Europe since Alan Kurdi died, according to the List.

Turkish military policeman Mehmet Çıplak was the first person to find Alan’s body, and his voice still shakes when he remembers what happened next. “I checked for a signal of life, hoping he was still alive,” says Çıplak. “I was so sad. I am a father first. I have a six-year-old son. I empathised, I put him in my son’s place. There was an indefinable pain. Beyond being a military police officer, I behaved as a father.”

Joy Gardner

Born: Jamaica, 1953.

Died: UK, 1993.

Joy Gardner was born in 1953 in Jamaica to a 15-year-old mother. She never knew her father. When she was seven, her mother moved to the UK to work. She would not follow her over until 1987, by which time she had a grown-up daughter of her own and was pregnant with her son.

She had the boy, Graham, while in Britain and sought leave to remain to be with her mother, but was refused. Although her mother was British, rule changes meant her adult offspring had no right to remain.

A team of police and immigration officers arrived at her north London flat without warning on 28 July 1993 with instructions to deport her and her son to Jamaica. She was bound, gagged and restrained with a body belt. She collapsed, fell into a coma and died of asphyxiation.

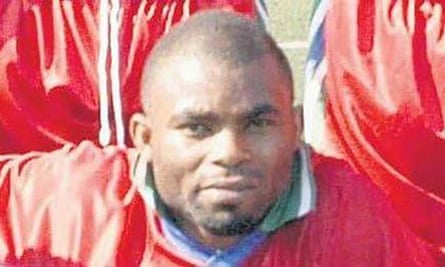

Festus Okey

Born: Nigeria, 1982

Died: Turkey, 2007

When he left Nigeria in 2004, Festus Okey dreamed he would become a great footballer in Europe.

“He was just a very cool guy,” said his brother, Tochukwu Ugo, who now lives in South Africa. “He was a very humble, cool guy. He wanted to go to London, and live a happy life.”

Instead, Okey got as far as Turkey. In August 2007, Okey was arrested by police in Istanbul, and shot dead while he was being questioned inside a police station.

In 2011, a Turkish policeman, Cengiz Yildiz, was sentenced to four years in jail for involuntary manslaughter, after saying that Okey’s death was an accident that occurred when the man tried to grab his gun. A murder conviction would have resulted in a life sentence.

During the case, the court heard that there was an absence of security footage from the police station, and the shirt that Okey was wearing at the time of the shooting disappeared. Campaigners said that forensic analysis of the shirt would have clarified the distance between Okey and the police officer at the time of the shooting. There were also reportedly cameras in all the other interrogation rooms.

Ugo, 42, says he has never understood what happened to his younger brother, who was arrested on drug charges. “A friend of Festus’s called me, and told me a little bit about what happened, but it still isn’t clear. He was shot, but I still don’t know why. They say he got into an argument with the police.

“It was so painful, hearing that. At first, I didn’t believe, but they sent me photographs, and it was him. It was so sad. They said it happened in the police station, but I never understood why it would happen like that in a police station.”

Ugo said that the family had faced serious challenges in Nigeria. “In Nigeria, the poor get poorer, and the rich get richer,” he said. “It was very hard for a long time.”

As an asylum-seeker, Okey struggled to work in Turkey. “I know he was having problems in Istanbul,” said his brother. “But he wouldn’t tell me about it.”

Alp Tekin Ocak, the family’s lawyer, said that the shooting had revealed serious problems within Turkey’s police forces. “The way the incident took place and the methods show us that those who have the authority to employ state’s monopoly of violence, have abused their authority. In this incident, there had been immense human rights violations, including violations of right to live, right to a fair trial and of prohibition of discrimination.”

Ugo said that Okey had spent in time in Gabon before attempting to travel to the UK. Instead of travelling directly to London, Okey got a visa to Iran, before continuing to Turkey.

“Before he set off, we spent lots of time talking, and hoping his journey went well,” said Ugo. “He had so many hopes, and I told him he was going to be great. I still can’t believe I am never going to see him again.”

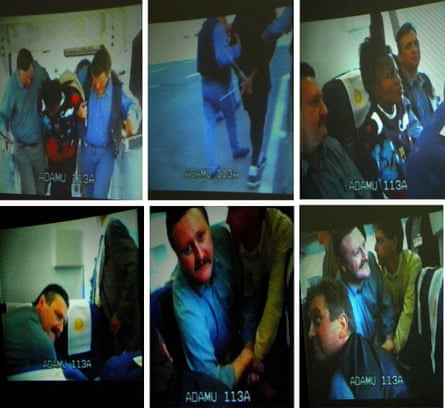

Semira Adamu

Born: Nigeria, 1978.

Died: Belgium, 1998.

Semira Adamu fled Nigeria to escape a forced marriage with a man three times her age back home. She was originally en route for Berlin, but when her plane stopped in Belgium she was forced to claim asylum there under so-called “safe third country” principles.

Her asylum request was refused and a team of 11 policemen were sent to deport her on 22 September 1998.

Amnesty reported at the time: “After being seated [on a Sabena aircraft] and bound hand and foot she began to sing loudly to attract the attention of fellow passengers.

“When officers then pushed her face into a cushion placed on the knees of one of them and pressed down on her back, she began to struggle. Her face was pressed against the cushion for over 10 minutes and she fell into a coma as her brain became starved of oxygen.”

Getu Hagos

Born: Ethiopia.

Died: Paris, 2003.

Getu Hagos entered France in January 2003 claiming to be a Somali called Mariame. His asylum claim was denied, and five days after his arrival he was dragged back on to a plane at a Paris airport. Air crew heard screams as the 24-year-old asylum seeker was forced into his seat. By the time the screams stopped, the Ethiopian man was dying.

In 2006, three police officers were charged with manslaughter over the 2003 death, with a court hearing that Hagos was forced into a “folding position” when he resisted the boarding process.

Stéphane Maugendre, Hagos’s lawyer, said that the young Ethiopian’s death had been one of a series of assaults on people facing deportation at the time. “We knew that they were being forced on the planes, and we knew that there was violence, but we couldn’t prove it. These things were happening regularly, but there was nothing we could do.”

The prosecutor found that two officials of the border police “were careless or clumsy,” with their actions leading to the death of Hagos.

Maugendre said that he had found the hearing frustrating, but was relieved that it went ahead at all. “I wasn’t surprised when Hagos died, but I was surprised that the prosecutor let us go to court. My real regret is that we weren’t able to go for a more serious charge. But we were so relieved to be able to go to court, and at least we got that.”

Maugendre said that Hagos had no family or friends in France, but that the Ethiopian community there had been very supportive of the case. “The local community really threw themselves into this battle, and that was very important,” he said.

The court heard that Hagos had claimed to be ill in the waiting zone of Roissy-Charles de Gaulle airport before being forced into an Air France plane to Johannesburg, South Africa. The officers said they believed Hagos was faking an illness.

According to reports, Hagos was hobbled with Velcro at the knees and ankles, but continued to resist, with one police officer saying that the man preferred to “die rather than leave”. The “folding position” involved one police officer keeping Hagos bent over in his seat, with another officer keeping pressure up on Hagos’s handcuffs, which were behind his back. A third officer occasionally pushed down on his head. Hagos is believed to have been kept in this position for 20 minutes before suddenly going silent.

According to medical evidence heard in court, the folded position resulted a lack of oxygenation. Hagos was in a coma for two days before dying. An autopsy found that he had suffered a “cardiorespiratory arrest”. The police officers said they had followed standard practice when someone attempted to resist deportation. They were all allowed to rejoin the border force.

- The List is being given away as part of a supplement with the 20 June print edition of the Guardian.