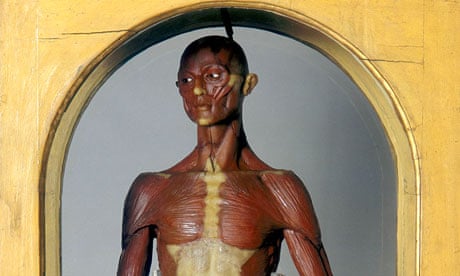

One of the most extraordinary – and most hidden – spaces in a city of rare and remarkable treasures is the suite of rooms in Florence's La Specola that houses the natural history museum's collection of baroque anatomical waxes (pictured). These halls are almost always empty of visitors, which renders first sight of their exhibits even more eerie: to walk into them for the first time is like entering a macabre fairytale. In glass cases lie full-sized female figures in wax, limbs delicately positioned to replicate feminine life: they wear pearl necklaces, they have real, waist-length hair, their skin gleams – and their bodies have been laid shockingly open to demonstrate the red and yellow organs of digestion and reproduction.

Around the pale-green walls vitrines show every imaginable body part sculpted in wax, depicting gestation, anatomy and disease with shocking vividness – and yet the most startling of the wax rooms' revelations is to be found in the teatrini of Gaetano Zumbo, the Sicilian master of wax Cosimo III summoned to his court in 1691 and the subject of Rupert Thomson's masterly new novel.

Created in the baroque period that followed the great flowering of the Renaissance, Zumbo's plague pieces, housed in miniature theatres of inlaid wood, are bizarre masterpieces, precisely evoking the intersection of art and science, of magic and reason that Florence once represented. With admirers as various as Herman Melville and the Marquis de Sade, they are infinitely more alive than tableaux usually are; their tiny figures, pinkly living or green with decay, evoke mortality and illustrate the transience of human glory alongside the stages of syphilitic degeneration. They are transparently the product of an imagination both possessed and unfettered, and as such it is hard to conceive of a more appropriate pairing of novelist and subject than that found here. Something of a literary Renaissance man himself, across eight novels and a memoir Thomson has moved like Zumbo with elliptical grace and genre-defying freedom between the surreal, the historical, the interior and the concrete modern worlds: he has been compared to JG Ballard, Dickens and Buñuel.

And in Secrecy all his considerable gifts – for binding an audience tight into his narrative, for rich characterisation, for originality of vision, for delicately intuiting a lost world as well as amply researching it – are exercised in parallel.

Opening in rainswept France with the dying Zumbo's visit to Marguerite-Louise of Orleans, Cosimo III's degenerate, estranged wife, the book quickly transports us back to the sculptor's arrival in Florence 10 years earlier. The Medicis' power – spiritual, cultural and economic – is in dramatic decline and the court to which Zumbo is summoned is a savagely repressive one. Adulterers and fornicators are transported about the city in bloodstained prison carts and the decapitated heads of sodomites are mounted on the battlements of the Bargello: for Zumbo, trailing rumours of nameless perversions since his abrupt departure from Sicily, it is already a dangerous place. Far from protecting him, the artist's patronage by the Grand Duke, involving as it does both a darkly secret commission and becoming Cosimo's confidant in a jealous court rife with spies and poisoners, winds him only tighter in the net.

When Zumbo falls in love with a subversive young woman called Faustina on the dubious margins of the Grand Duke's circle and uncovers a labyrinthine treachery, all the elements of a deeply satisfying page-turner are in place – while at the same time more subtle pleasures are also in play.

As he unfolds his narrative, moving from Florence to Sicily and back again, dipping into the intrigues of the court and tracing the city's geography, building character and layering historical and psychological detail with deliciously measured slowness, Thomson transcends genre pretty effortlessly. He doesn't scrimp on the many satisfactions of a historical novel – in particular an exotic profusion of detail, from the composition of wax (beeswax, carnauba, leadwhite) to the construction of baroque fireworks, from vultures and peacocks in the Boboli gardens to the scent of violets at a Medici ball – and he provides an unstintingly gripping thriller plot into the bargain.

But what lifts Secrecy to a more rarefied level altogether is the visionary imagination that overlays the scrupulously worked structures those genres demand. It informs the brilliance of Thomson's characterisation, from the morbid monomania of a tormented Cosimo, to the brutish, coiled savagery of the Dominican enforcer Stufa, to the ghostly sadness of a neglected child. Along with a particular poetic gift for laying the exquisite alongside the visceral, it enables him to evoke Florence's peculiarly sinister magic to perfection, and to thread together the real, the historical and the purely imagined with such loving attention that I defy readers to see the join. Indeed, the join becomes irrelevant.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion