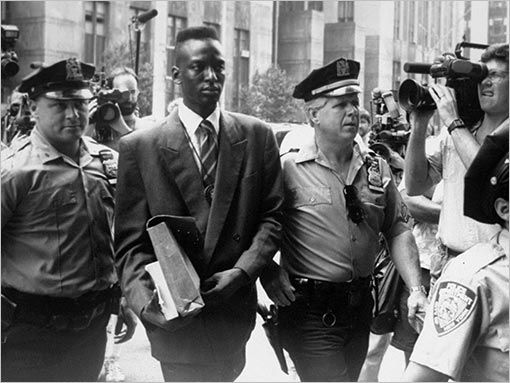

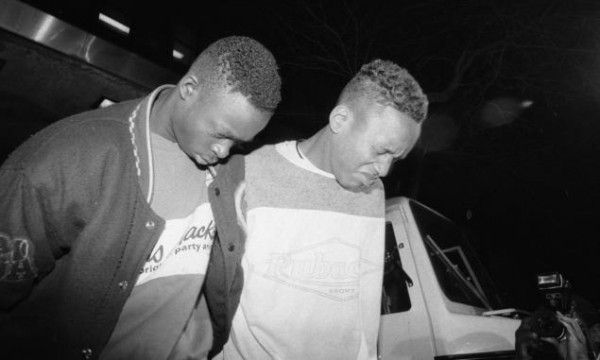

The Central Park Five is a compelling documentary from award-winning filmmaker Ken Burns about the five black and Latino teenagers from Harlem who were wrongly convicted of raping a white woman in New York City’s Central Park in 1989. Directed and produced by Burns, David McMahon and Sarah Burns, the film chronicles the Central Park Jogger case, for the first time from the perspective of the five teenagers whose lives were upended by this miscarriage of justice. Hit the jump to read the interview with Ken Burns and Yusef Salaam, one of the Central Park Five. Burns also talked about his upcoming projects, The Dust Bowl, The Roosevelts, Jackie Robinson, and Vietnam.

Before getting to the interview, here's the trailer:

At the film’s press day, Burns and Salaam talked about how the events in 1989 dramatically altered the lives of five teenagers, how law enforcement, social institutions and the media undermined the very rights of the individuals they were designed to protect, why the tragedy reminds us of how much we still struggle to come to terms with race in America, and why the film provides a lens through which we can understand. Burns also discussed the outstanding value PBS delivers by bringing our communities together, and how he could not exist as a documentary filmmaker without it.

Question: This is an excellent film and especially important because it’s still timely. What was the most difficult aspect of doing this film?

Yusef Salaam: I don’t know if there was anything particularly difficult to do in reference to the film other than reconnecting with the feelings that happened back in 1989. As you go through a traumatic experience, unless you have finances like that, no one ever says, “Okay, this is what was done to you so therefore let’s get you some type of help.” I found that speaking about it, and speaking about it in front of groups, on a one-on-one basis and things of that nature, is a tremendous help. It’s almost therapeutic, because for the most part, most of us, probably all of the five, had already resigned our lives to being those guys that were framed, those guys that were railroaded. It’s unfortunate because I was already out on parole. I had already finished my parole term, and I had just been informed that I was going to have to be registering for the rest of my life under Megan’s Law as a Level 3 sex offender. They considered me a sexual predator. And so, when I thought about all of that, I had said “Shucks. I guess this is my life.” It wasn’t until 13 years later which is, I don’t know if in all people’s cultures, but in New York or United States culture, 13 is supposed to be an unlucky number. So 13 years later, the truth came out and it was like a breath of fresh air. But it’s been a hard road to walk, because since then, we are still fighting the system for some semblance of justice. They said “Okay, we’re going to overturn the charges and we’re going to reverse everything and wipe your slate clean as if you’d never done time.” But we were in prison. We did time. We really went through all of that. It’s not particularly difficult, but it’s been… (turning to Ken Burns) not being the movie person, it’s going to sound funny me saying this, but it’s been a labor of love.

Ken Burns: Yes, it has. Well, it has for us.

Salaam: For us to get back into that reconnection and for it to be therapeutic.

Burns: This is the story of 13 years, as Yusef says, of justice denied. And now it’s almost 10 years of limbo.

Salaam: Yes.

Burns: Which is justice delayed and which we also know is justice denied. And that is a terrible thing. And so, our film is solely about the events from April 19th, 1989 to the vacation of the convictions in December of 2002. But this is something that has ramifications for lives and families of the people involved and for the city of New York. You want healing, not just for the officials, not just for the five, but for the whole city. This has been a festering wound for way, way too long, and we hope that in some ways the film can be an agency of that healing.

Ken, can you talk about how you first became involved in this project and what inspired you to make the film?

Burns: I’m involved in it because of my daughter. I remember the original case. I remember the outrage at the sense that our society had decayed so much. I remember reading about the convictions being vacated and thinking this is not getting any attention. Race has been a central theme of nearly every single one of the films I’ve made, not that I go look for it, but because when you scratch the surface of American history, you have race there. We are founded on the principle that all men are created equal, right? And the guy who wrote those words owned more than a hundred human beings as he wrote them and didn’t see the contradiction, or the hypocrisy, and never once thought about freeing any one of them in his lifetime. That’s our original sin as Americans. It’s always there if you’re investigating American history. I made note of that. And then, my daughter, Sarah, became familiar with the case and decided to write a book about it, and as she was writing the first draft, she was sending me the pages. I was stunned. I realized oh my God, this is just a perfect story. This is the same story that has compelled the reason to do The Civil War or Baseball or Jazz or [Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of] Jack Johnson or Thomas Jefferson -- we’ve made a biography of that same Thomas Jefferson -- and many other films that we’ve worked on. It was her impetus. She wrote a book. By the time the book was published, we had already been well into not only the production of this film but the editing of it and feel that they’re two complimentary things. It gave us, our family, -- the editor and the assistant editor and Sarah and Dave and me, and she is my daughter and he is my son-in-law -- the opportunity to bond with another family, an improbable band of brothers who were forced by circumstances together. And, as Yusef said so much better than I could, there is something about this that is positive in that we’re together on this, and we feel this, and hopefully it is therapeutic to bring it up. But it’s also therapeutic for all of us. Let’s get out there and let’s talk about it. Why has it taken so long to settle this case?

Salaam: Also, I just wanted to say one quick thing about that, too. How could something like this happen? I don’t know if this is the best word to use, but in New York terminology, they would say this was such a sexy case that it made sense. It made sense that this large group of guys did this, when in fact, that’s not what happened at all.

Burns: In fact, the media was so responsible for the hyperbolic atmosphere -- the wolf pack, the wilding Black beasts -- all of this language not of a progressive city at the end of the 20th century, but of Jim Crow America in the South just before you justified why you strung an African American up for an invented crime. So this is the language of not just racism but of murder, and this is what’s so appalling to all of us when you realize what’s happened and what they’ve been through.

I knew of this case because it originally received such intense media attention. But their innocence never got the attention their guilt did. If it weren’t for seeing your film, I would have never known that the Central Park Five had been exonerated.

Burns: Look, let me just tell you, in fact, the City of New York will push back on that saying they’re not exonerated. They’ll try to hang you out to dry on technicalities. They vacated the convictions. That’s what they did. They say “Wipe the slate clean.” It is the obligation of the media to tell the whole story, not just get involved with what the cops fed them about this, but to investigate stuff. And now, we have an opportunity to go back and say “Why did this happen?” And then, let’s go to some other things that are left hanging in our film, that ought to be the provenance of what you guys all do, and I don’t mean that specifically. But on April 17th, two days before Tricia Meili was brutally raped by Matias Reyes in Central Park, he assaulted another woman, and it was broken up, and she noticed that he had stitches, and they identified him. On the 17th, they knew who it was and they never followed through on that. Why did that happen? Why was that case closed? Why, later on in the summer, when they caught Matias Reyes, did one of the detectives wish to reopen that case, but Linda Fairstein said no? Why are all these things not being pursued with the same sort of energy that the press … The real wilding was the press. They’re the ones that acted as a wolf pack. Nobody said “Well, who are these people?” Let’s just remember a couple of weeks ago a guy named George Whitmore died. He was an African American who in the early sixties was charged with a murder. He came in to try to help the police and they ended up getting him to confess a whole bunch of stuff, and the media sat up and said “Wait a second. This stinks. This doesn’t make sense. He has alibis.” They followed through on alibis that the cops didn’t. So, as a result of freeing this guy, we have Miranda. As a result of their case (referring to the Central Park Five), we have the death penalty reinstated in the state of New York. So, a lot of people didn’t do their jobs, as Jim Dwyer says. (New York Times journalist Jim Dwyer) Cops didn’t do their jobs. Prosecutors didn’t do their jobs. And the media didn’t do their jobs. And that’s something that we now have an opportunity to correct.

Were you surprised when the City of New York started pushing back and subpoenaed notes and outtakes from the film?

Burns: Well, they subpoenaed us on September 12th, all of our outtakes and all of our notes and things like that, and we just said “No thank you. We’re not going to comply with this.” That’s now in its own legal thing and so I don’t feel compelled or obligated to talk about the details of that. But, I think it’s part and parcel of individuals now protected by the city, that if they were to examine it, has no interest in protecting those individuals from doing what all of us do in our lifetime, which is “Gee, I screwed up.” Admit your mistake.

Salaam: And that’s so simple to do. It almost causes the human side of you to come back out, that humanity that is always present for a person to say “I’m sorry we did this.” In large part, it was continuing to happen until Sarah got in contact with us and started the idea of putting a story together about this. We were almost dying a social death.

Burns: They didn’t exist. Nobody said “Who are they?” Nobody asked them about their humanity. Nobody said “Who are you?” until Sarah came along, until we came along and said “Who are you?” We would have been happy to interview the prosecutors and the cops. We know why they didn’t do it because they couldn’t answer half our questions. They (referring to the Central Park Five) answered all of our questions and they revealed themselves. The camera is a kind of polygraph, and when you look at the film, you see the way Elizabeth Lederer, the prosecutor, looks in her eyes. She looks like she’s ill. She just won a big case, the first of two trials. She looks miserable. She always looks miserable like she knows somewhere. In some ways, the film reveals them, the Central Park Five, for who they are, for the men they are, and it reveals all the other participants, even those that didn't grant us an interview. The record, the archival record that we spent so long trying to assemble, is in a way a complicated, artistic polygraph test.

Usually when you’re convicted of brutally beating, raping and nearly killing someone, you are put away for life, but these guys weren’t.

Burns: Well, she wasn’t killed. They were minors, with the exception of Korey (Wise), who was tried as an adult and served a much longer term. So, they served out their full terms without the benefit of being let go early because they weren’t admitting their guilt, because they hadn’t done it, and they had to register as sex offenders. Can you imagine being innocent, serving out your time, and then have to be sex offenders, as they said, for the rest of their life until this? Who has the real conscience here? Well, it turns out the sociopathic rapist suddenly looks at Corey at Auburn Prison and goes “He’s doing time for something I did. I’m not going to get out of here in a really long time.” And so, he comes forward and he admits it. Did the cop who arrested Matias Reyes, or was there on the perp walk with him, and was also there interrogating, go “Wait a second”? “This is the same MO as the 17th and all these other things. I may have made a mistake. I think these kids are in jail.” If he had done it that summer, these guys would have said, “Okay. Whew! Three months in jail. We dodged a big one.” No. Did the prosecutors go “There’s no DNA? What? Maybe we ought to try alternative scenarios.” [If that had happened,] we wouldn’t be here. The film would disappear. We wouldn’t be here talking to you. But we’re here because the only person who actually, strangely enough, had a conscience in this was Matias Reyes, a sociopathic rapist. Help me understand how this is. This is where the outrage comes from. Where was the press saying, wait a second? If your timeline is true, then how is she raped at this time, but this pack of boys is down here either doing or observing this hassling of a jogger and this assault on this person? How does that happen? This is a bloody crime scene. How come there’s nothing of this bloody crime scene on the boys and how come there’s nothing of the boys on the crime scene? Who’s not asking these questions?

How do you feel today in light of all that has happened -- after being falsely accused, pilloried in the press, subjected to invented phrases for imagined crimes, convicted, sent to prison for years, and then suddenly the convictions are vacated?

Salaam: Corey said something to the audience at a recent screening at the SVA Theater in New York, in Manhattan. He said “God is good.” It’s the recognition that you can put one foot in front of the other, the recognition that you have some semblance of sanity, the recognition that you’re able to continue your life a little bit more. It’s like I said, had this truth never come forward, had the real story of not only what happened to the Central Park Jogger but now you have more than her being victimized. Now you’ve got the five of us. I always call it psycho-social, and I’m not sure that is the correct terminology. Someone told me that means when society kills you by slamming every single door in your face. If you try to go get a job, your records are there. They can look at it and say “Uh no, that’s the guy. Sorry, even though our application says this will not discriminate against you, yeah, you just don’t have the qualifications.” I’ve been actually very fortunate to be given opportunities. So, in many ways, I look at had this not happened to me… One of the aspects of our lawsuit is what would he have been had this not happened to him? I’m actually making close to $100,000 right now. I work in health care. I work in technology. But it’s like I’ve been given those opportunities. You see? Now imagine if this was given to me years ago, I would have been way well off.

Burns: Can I say something to what he’s saying about God is good? Filmmaking is essentially about entertainment, but it’s amazing to realize that it has this other muscle that could actually help. Do you know what I mean? People permit entertainment to wash over them, but every once and a while, entertainment – and this is entertaining – also galvanizes something else and that would be a really good thing to have happen in this case.

Salaam: So many things would have been different. Because people have said wow, you know, I’m going to take a chance on you, it’s given me time to be humble, time to be thankful, but also, I’m always scared. I just went into a brand new job and the fear is, do these people know who I am? Are they friends or are they foes? If they find out who I am, are they going to find some way to get rid of me? I always, always think about that.

Burns: This is a prison that they cannot be liberated from until this thing is done.

Were you one of the people who took advantage of the prison education program and went to college while you were in prison?

Salaam: Yes. They took the program away.

Burns: So Corey and Antron (McCray) didn’t get it. Antron worked in a tailor shop, but Kevin (Richardson), Raymond (Santana) and Yusef all got degrees, which is another reflection of nobody checked up on them.

A good movie should be entertaining, exciting. It could be educational. It could be emotional. And this is what this is.

Burns: All of those things.

There’s an interesting moment in the film when a couple of people being interviewed describe how they felt when they heard the news that an unidentified white woman had been raped and how they hoped the crime wasn’t committed by someone of their race.

Burns: It was two people, an African American reporter named Natalie Byfield and Craig Steven Wilder, an African American historian. It was “Oh God, please don’t let it be one of us” when you hear about something bad. And that’s what we struggle still to try to heal, that we don’t look at the other and see the color of the skin but the content of the character. I think what this film does is actually go right to content of character. And it turns out in this case, the color of the skin has nothing to do with it. Content of character comes from within. And I am, of course, paraphrasing and not attributing, as I am now doing, Dr. King.

I read an article recently on CNN about power, politics and race relations in America that drew parallels between the time immediately following the Civil War, the Jim Crow era and today. It’s 2012 now. Has anything changed?

Burns: Yes, of course it has. First of all, we’re here. (turns to Yusef) We’re friends.

Salaam: Yes.

Burns: We have an African American president. We have made extraordinary gains. The music that is the music of America is as much African American as it is anything else. The only art form that Americans have created that’s recognized around the world is jazz music born in a community that had the peculiar experience of being unfree in a free land. Some of the greatest sports [figures], some of the greatest actors, we have done a lot. But clearly, we haven’t done enough if we can still squint our eyes and can’t tell the difference between 1989 New York City and 1905 Macon, Georgia. That means there’s an awful lot to do and that’s what has compelled a lot of my work, but it certainly informs the kind of collective vibe, the emotion as you say, that comes out of this film. Do you remember in 2006 the white Duke lacrosse players that somebody had falsely charged? Remember that? Do you know what happened? The prosecutor was fired. The prosecutor was disbarred. The prosecutor went to jail for inconveniencing for a few weeks these white kids from Duke. I rest my case.

Salaam: The prosecutor in our case was able to retire and…

Burns: …parlay this into a career as a writer of fiction. I’ll say no more other than she writes fiction. Linda Fairstein does.

The one thing we get out of your movie is how all five of you guys have survived and it’s beyond a miracle. I took that away with tears in my eyes at the end of the film. It’s so moving.

Burns: It is moving in the extreme and let’s qualify that success, because Yusef is absolutely right, that had not that period been robbed from him, who knows where he would be. Maybe we would be talking to Senator Salaam. We don’t know what was robbed. It may be President of the company that he works for. We don’t know. And each has experienced varying degrees of survival, so nobody is out of the woods yet.

Ken, how happy are you for your daughter?

Burns: (laughs) This is a family drama and this has been so amazing to first of all work with a little girl who used to be crawling as a toddler underneath the editing table when we were working on films 28 years ago and is now a 30-year-old woman and the producer of this film, and also with her husband, and a co-producer with her husband of my granddaughter. I can’t begin to tell you what an amazing thing it’s been. If she were here, you’d realize why I should shut up and she should talk because she’s really something else and so is Dave (David McMahon). This is a film made equally by the three of us, and kudos too to Michael Levine, the editor, who has worked with us and knew Sarah when she was a little girl and now Sarah is his boss.

What do you have coming up? I know you’re working on a lot of things.

Burns: Yes, we’re more than that actually. We’re simultaneously releasing and broadcasting on November 18th and 19th a 2-part, 4-hour history of the Dust Bowl, which is the worst man-made ecological disaster in American and perhaps world history, certainly American history, and it’s superimposed over the Depression. We’re doing the finishing work on a 7-part, 14-hour history of Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, an intimate portrait which believe it or not has not been done, both the combining of all three in a family story but also that. We’re shooting two films, one on Jackie Robinson, who was the first African American to integrate the modern era of Major League baseball, and a major series, 7 parts, 14 hours on the history of Vietnam which we are about two-thirds of the way shot. The Dust Bowl is right now. This film is next year on PBS. The Roosevelts is 2014 and Jackie Robinson is 2015. Vietnam is 2017. We’re actually researching and writing a big series on the history of Country Music and a biography of Ernest Hemingway. So that’s just the stuff that I’m producing and directing. There are other things that we have our hands in. But these are not ideas on paper. Most of them are fully funded or close to being fully funded. As part of my job, one of the hats I wear is the Chief Fundraiser in Charge. We’re grateful for the folks in this film – PBS, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Atlantic Philanthropies, and Bobby & Polly Stein -- for taking the risk. A lot of our traditional funders had moved away and passed on this difficult topic.

I cringe when I hear about people who don’t know about PBS and say they want to take PBS away. I think of all the good work that those people have done on PBS.

Burns: The best science, the best nature, the best children’s, the best public affairs. I’m told the best history, the best public performance things are on this underfunded, much maligned network that has one foot tentatively in the marketplace and the other proudly out of it.

Where would you be without PBS?

Burns: I would not exist. It is 1/100th of one percent of the federal budget. But one of the candidates in this election is hell-bent, even so far as to going and isolating it in the first debate, and saying he wants to get rid of it. To me, that tells me that he knows something about what the costs of things are, but has no idea what their value is. It’s short-sighted. It’s uninformed. And what he doesn’t realize is that it’s not a Blue State phenomenon. It stitches together even more Red States – Alaska, Oklahoma, Arkansas, West Virginia, our rural communities that depend not only on this phenomenal prime time, but on classrooms of the air, of continuing education, of Homeland Security reports and crop reports, stuff they’re not going to get anywhere. They helped us stitch together these communities. Public television is supported by an overwhelming majority of Republicans and Independents and Democrats. To pick on Big Bird is ridiculous. Big Bird is yellow, but I think it takes a yellow streak to do that.

Speaking of PBS…

Burns: (laughs) Don’t get me started!

The regular networks have dropped the ball…

Burns: …on everything.

In Los Angeles, KCET stepped back from doing the nightly news, and now you have to fight to find public television here.

Burns: I talked to a very, very conservative Republican congressman who told me, “If Fox or NBC or even the networks told me that the Chinese had invaded New Brunswick and were moving into Maine, I’d go turn on the NewsHour or All Things Considered to find out if that was really happening.” And this is from a very conservative Republican. So, we’re proud to have it and we’re thrilled to be a part of the festival circuit. We’re thrilled to have a theatrical release. But we also know that we have the opportunity to reach tens of millions of people with this film when Public Television broadcasts it, which has been the experience of the other films I’ve done. You couldn’t aggregate a top grossing film and reach as many eyeballs as we will be able to.