Reproduction Revolution: How Our Skin Cells Might Be turned Into Sperm And Eggs

Summary

Forty years ago, couples suffering from infertility were given hope by the birth of Louise Brown, the first “test-tube baby”. But although millions of babies have now been born by IVF, the technique can offer no help to couples eager to have a child that is genetically theirs but who lack the eggs or sperm to make it: men whose testes produce no sperm, say, or women who have undergone surgery for ovarian cancer. Some opt for donor eggs or sperm, but an alternative may be on the way. Scientists are making steady progress towards creating human eggs and sperm – the so-called gametes that combine in fertilisation – artificially in a petri dish.

The idea is to make them from the ordinary “somatic” cells of the body, such as skin. The feasibility of such an extraordinary transformation of our flesh has only been recognised for 11 years. But already it is revolutionising medicine and assisted reproductive technologies may eventually feel the benefits too. If gametes grown in vitro prove safe for reproduction, the possibilities are dramatic – but could also be disconcerting, and might go well beyond providing eggs and sperm for those who lack them. Instead of having to undergo a painful egg-production and extraction procedure involving doses of hormones with uncertain long-term effects, a woman could have an almost limitless supply of eggs made from a scrap of skin. Huge numbers of embryos could be created easily and painlessly. What might we do with such a choice?

…

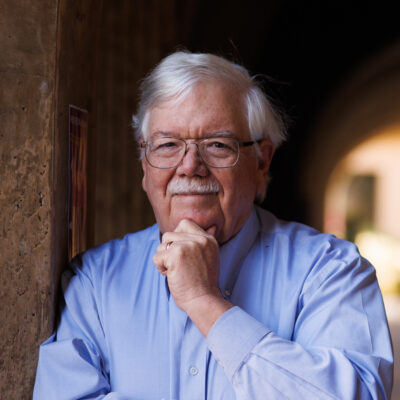

…All the same, says bioethicist Henry Greely of Stanford University in California, “I don’t see any show stopper that will keep what is feasible in mice from working in humans.”

If eggs and thus IVF embryos could be produced easily and in large numbers, says Greely, that could change the landscape of assisted conception when combined with the option of genetic screening. This can be done ever more cheaply and quickly for embryos and is currently permitted in the UK for identifying those carrying certain genetic disease mutations.

With such technologies in place, says Greely, “the stage is set for very, very widespread use of embryo selection”.

He foresees a day when IVF clients are presented with lists of characteristics for dozens, perhaps hundreds, of their embryos: this one a male with dark eyes and light brown hair and slightly above average risk of prostate cancer, that one a tall, dark-haired girl with a 55% chance of being in the top half in Sats tests. Given that option of choice, Greely suspects that IVF might eventually become the default method of human reproduction. “I expect that, some time in the next 20 to 40 years… sex [for reproduction] will largely disappear,” he writes in his 2016 book The End of Sex.

…

Making artificial gametes could introduce new permutations into how we reproduce. The somatic cells of both men and women could in principle be transformed into eggs and sperm. So gay couples of both sexes could have babies that were genetically related to both parents, although male couples would need a surrogate mother. Rather more challenging is the notion of a single individual conceiving a child from eggs and sperm both made from his or her cells, what Greely calls the “unibaby” of a “uniparent”, which could become some grotesque vanity project. Equally disturbing is the prospect that genetic parents could include, say, the very elderly, children or even foetuses. The ability to make gametes from any bodily residue we leave lying around – “like cells you leave on beer bottles and wine glasses,” says Greely – opens up other alarming scenarios. You can imagine the celebrity paternity suits already.

Read More