Over at Crunkfeministcollective, Brittney Cooper, a gender and race-studies professor at the University of Alabama, has a moving commentary on the scandal over pastor Creflo Dollar, whose 15-year-old daughter recently accused him of physically abusing her. What troubles Cooper is not just the incident itself—Dollar denies the abuse, and we don’t yet know exactly what happened—but that so many in Dollar’s church (and in Cooper’s own) utterly refuse to entertain the possibility that Dollar’s daughter might be telling the truth, that this successful and admired preacher might be not as virtuous as he says he is.

A bit of background, in case you haven’t been following the saga of Dollar, the Atlanta megachurch leader primarily known for his preaching of prosperity gospel, which teaches that God wants his faithful to be rich. According to both Dollar and his daughter, the two got into an argument last week when he told her that she couldn’t go to a party. Precisely why and how the argument escalated is what’s in dispute. In a police report taken after the 15-year-old called 911, the girl stated that after she walked away from Dollar and told him she didn’t want to talk to him anymore, he put his hands around her throat and briefly choked her, then threw her to the ground, punched her, and hit her with a shoe.

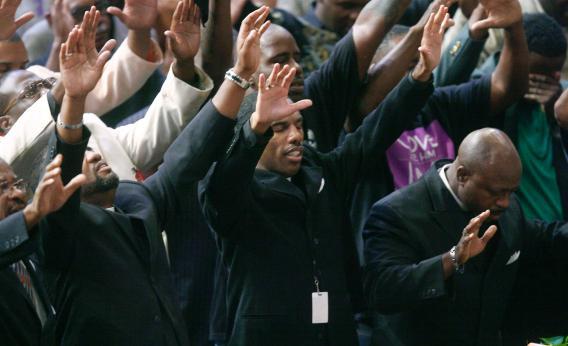

The substance of this story—slapping, brief choking, throwing to the ground and hitting—was backed up by testimony from Dollar’s 19-year-old daughter, who said she witnessed it. Dollar, meanwhile, says he merely restrained his daughter, and that when she began to hit him, he wrestled her to the floor and spanked her. Dollar was arrested and charged with simple battery and cruelty to children, then released on $5,000 bond. In a sermon a few days after the arrest, he told his congregation that he didn’t choke or punch his daughter, that he should never have been arrested, that the real culprit was “the devil,” who was trying to discredit him, and that “all is well in the Dollar household.” He likened his trials to those of the Apostle Paul.

The event has caused a good deal of debate over physical discipline, which may be more alive and well than some of us had realized. (I had no idea that corporal punishment is still legal in Georgia schools.) At the Washington Post website, for instance, Barbara Reynolds suggests that not only was Dollar justified in whatever he did, but that if he managed to teach his daughter a lesson, jail was a price worth paying. “If I could load up a bunch of bad kids across the nation and bus them to Pastor Creflo Dollar’s mega-church in Atlanta for a good old-fashioned smackdown, I would certainly do it,” Reynolds writes, before going on a bizarre rant about “knuckleheads” who wear their pants too low, “showing their underwear.”

At Crunkfeministcollective, Cooper suggests that if the account of Dollar’s daughters is true, the incident constitutes domestic violence. And she’s troubled by the fact that few of Creflo’s followers seem to even consider the possibility that his daughters might be telling the truth. Instead, the pastor is still getting standing ovations. The immediate assumption that both girls are “bald-faced liars” is deeply troubling, she writes, and it surely makes other women who’ve been victims of violence hesitant to step forward and tell the truth.

What would it look like for our faith communities to be places where Black girls could testify about the violence they experience from the men in our communities and be believed?

Of course, this isn’t a problem unique to the black church. Reading about Dollar, I couldn’t help but think of the hubris of the leadership of the Catholic church, which for so long refused to acknowledge the wrongs of its sexually abusive priests. Just as Dollar should not be convicted without a trial, neither should his daughters’ statements be dismissed as impossible without investigation. We have had enough lessons in the fallibility of our spiritual leaders to know that it’s possible for the high and mighty to do wrong.