The Lonely Lives of Dolphin Lice

Crustacean parasites are common on whales, but how they survive on smaller, speedier ocean animals is a mystery.

It’s hard to muster sympathy for lice. Most of the parasites seem to be doing fine—living, feeding and multiplying on their hapless hosts. But lice that live on dolphins have it tough. Their hosts are slippery and fast-moving; the lice spend their lonely lives clinging tight and hoping to meet just one other louse they can mate with. And while these parasites can teach scientists about the evolution and behavior of ocean mammals, it’s not clear how the lice themselves survive at all.

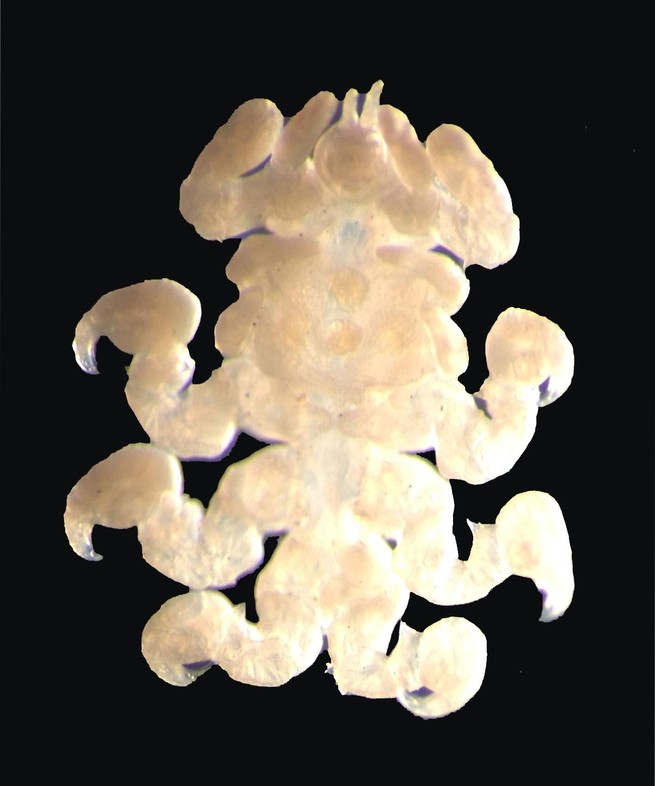

Syncyamus aequus is a whale louse, but it doesn’t live on whales and it’s not really a louse. The 30 or so species called whale lice are crustaceans, like crabs—not insects, like the lice that live on humans. Each species infects certain kinds of cetaceans (the group that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises); S. aequus only lives on dolphins. Whale lice do have some similarities to human lice: They can only live on a host’s body, and they spread when two animals rub against each other. But whale lice feed on skin, not blood. And their hosts live in the ocean.

“The main problem for whale lice is how to minimize the chances of being washed off,” Natalia Fraija-Fernández and Francisco Javier Aznar, of the University of Valencia in Spain, told me over email. To dig in and hold on tight, the lice have evolved flattened bodies, sharp claws on their legs, and spiny bellies. They hunker down in skin folds and other relatively protected spots.

It’s not easy to study the lice that live on elusive underwater animals. Researchers managed some studies back in the days of commercial whaling, Fraija-Fernández and Aznar say. These days, scientists can study the parasites in countries where whaling is still legal, or try to grab them off of slow-moving whales in the wild. Or they can wait for a whale to be stranded or accidentally killed.

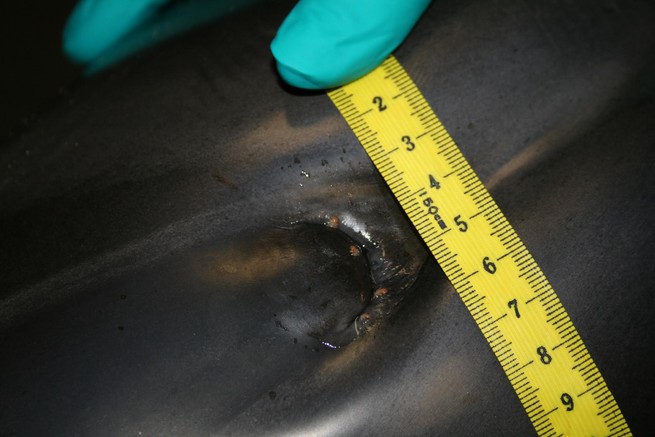

Because fast-swimming cetaceans like dolphins don’t slow down enough for anyone to pick parasites off of them, scientists know even less about the lice that live on them. Fraija-Fernández, Aznar, and others at the University of Valencia’s Marine Zoology Unit study cetaceans with the help of a stranding network. When an animal comes ashore, researchers gather data on it as well as any other life forms it’s carrying. Between 1980 and 2016, they managed to study 176 striped dolphins and their whale lice. (When working with animals that can only be collected by chance, Fraija-Fernández and Aznar point out, “one must be patient.”)

Syncyamus aequus was the only louse species on the striped dolphins. And its numbers were sparse on these swift, streamlined hosts. Only about a quarter of the dolphins in the study had lice, compared to 100 percent of whales in some surveys. And while one whale can have thousands of lice onboard, infected striped dolphins carried fewer than five lice on average. More than a third of infected dolphins carried only a single louse. “We expected low infection levels,” the scientists say, “but not so low.”

The dolphins’ lice were smaller than lice living on whales. And they had found only a few places to tuck their little bodies into. Most lice were around dolphins’ blowholes, with some around their eyes or in the corners of their mouths. This was another sharp contrast to whales, where lice find abundant habitats. In addition to a whale’s skin folds, lice may live around the rough, whitish patches called callosities, or in a whale’s throat grooves, or even in the spaces between barnacles attached to a whale’s skin. Whales can carry three or more species of lice at once, each carving out its own territory.

Those bustling louse populations on whales have complex dynamics. Female whale lice can only mate right after they molt, so males jealously guard them during this period. They may chase away other males, or even lift up a female and carry her away. Males are larger than females in most whale lice species.

But in S. aequus, the researchers found, the opposite is true: Females are bigger. The researchers suspect that’s because there’s no competition between males. In fact, the lice barely see each other at all. A male louse living on a striped dolphin is lucky if it meets even one female louse in its life. Female lice may have evolved to be bigger so they can lay more eggs—assuming they ever find a mate.

Studying the parasites of whales and dolphins can help scientists answer questions about the whales and dolphins themselves. In 2005, for instance, researchers studied the population histories of right whales by looking at the mitochondrial DNA of their lice. In 2004, after a southern right-whale calf stranded and died, researchers found that it was infected only with humpback-whale lice—a tantalizing hint that the whale calf might have been nursed by a female of a different species.

Fraija-Fernández and Aznar say their study also has interesting implications about the evolution of S. aequus lice themselves, such as how sparse populations affect the size differences between males and females. And they still don’t know how these lonely lice manage to move between dolphins. Sex would seem to be a good opportunity, but no lice turned up in the dolphins’ genitals, suggesting this isn’t how they spread.

“It is incredible how these creatures manage to live on such a harsh habitat,” the researchers say. “We are still amazed.” Maybe this louse doesn’t need our pity after all.