Art World

Kenny Schachter’s Dealer Diary: Of Art and Cars, Part II

Thea Westreich was not much of a Schach fan.

Thea Westreich was not much of a Schach fan.

New York, New York

Back in New York, I attended the thoughtful and lucid (anti-zombie) retrospective and dinner for hard-edged geometric abstractionist Carmen Herrera who has been anointed a full-blown art star at the ripe age of 101.

The paintings would pair well with the looser but equally vividly-colored works of the similarly underappreciated (and undervalued) artist Mary Heilmann.

A collector at my table commented that “Table 1” where we were seated, signified the number one target for contributions. Uh oh. I had to stage a hasty getaway (after the cake, of course). He also mentioned high prices shut down his collecting. But Herrera was an art world rarity, an almost Disneyesque, feel-good story—offering hope for all of us late bloomers.

Meeting dealer Edward (whose name spell-checks to “resale”) was a perfectly pleasant experience. A man-boy in his early twenties, younger than I thought he’d be after his Instagram caught my attention, Ressle’s social media pages are replete with a who’s who of contemporary art market darlings.

Impressive and formidable, the pieces on his gallery website wouldn’t be out of place in the SF MOMA, New York’s MoMA, or any other MOMA for that matter. Indeed, I discovered just prior to my visit that many of the advertised pieces on his site and on his gallery page at artnet.com belong to others, whether from institutions like François Pinault or punters like me! Was there some sort of conceptual hijinks afoot—a virtual art gallery with no art, a fictional construct, a Richard Prince joke?

Across two floors, there were two Prince Instagram canvases; unusually for the series, both were under Richard’s account. There were books everywhere, on American Fine Art’s Colin de Land (Ressle didn’t seem too familiar with the achingly innovative 1990s impresario), Mike Kelley, Joe Bradley, Bruce Nauman, Christopher Wool, Rudolf Stingel, Richard Prince (of course), Wade Guyton, Mark Grotjahn, et al. Yet there was nothing else to be seen and none of the works featured on his sites by the artists above belong to him and I don’t suspect they ever did (or even pass through his business). At least I was in good company; other owners of works he’s promoting (hey artnet, listening?) included the Mugrabis, Valentino, and Hugh Gibson.

Anyway, hanging art is probably unnecessary in today’s shortsighted, fair driven art world. Besides, why not do away with holes in walls to boot? He did offer me an excellent (but minor) late 70s Prince photo of watches for $100,000 and after I asked for his best price he replied $110,000! Um, I wasn’t asking for a better number for him unless that’s worked before, I doubt it. Ed, I trust you understand I’m just playing.

His folks are in the business as well, he said, and his space, around the corner from the MET Breuer, is elegant and promising. I wish him well.

Goshka Macuga. Courtesy of Andrew Kreps.

There was so little time and so many shows to see (other than at Ressle), New York’s gallery-land is unprecedented globally and makes the London scene seem anemic. I hit Goshka Macuga (if not for the great art, for the name alone) prior to the September 15 opening of her show, International Institute of intellectual Cooperation at Andrew Kreps.

Andrew, a longtime friend (somehow) was kind enough to unlock the door to a staff meeting with the artist to let me attend. I was emboldened to raise my hand about how the heads were made for the large-scale sculpture in the show: turns out she developed an aptitude whipping out progressively convincing and accomplished works that manage to look a little slapdash at the same time. I adore them, tying together disparate figures from Einstein to Frankenstein, connected by rods that resemble molecule models.

Matthew Barney’s chiseled body was on full display in video work at Barbara Gladstone in a restaging of his first (1991) show with her. Seen in videos clambering around the gallery starkers save for a few bits and bobs shoved up his butt, Barney’s is a creepy, internally self-lubricating post-future made up of prosthetic plastics and petroleum jelly.

Having seen both shows 25 years apart and not crazy about his indulgent everlasting filmic extravaganzas laden with symbolism knowable—if at all—only to the artist, I thought it looked better than great and really gelled (sorry, again).

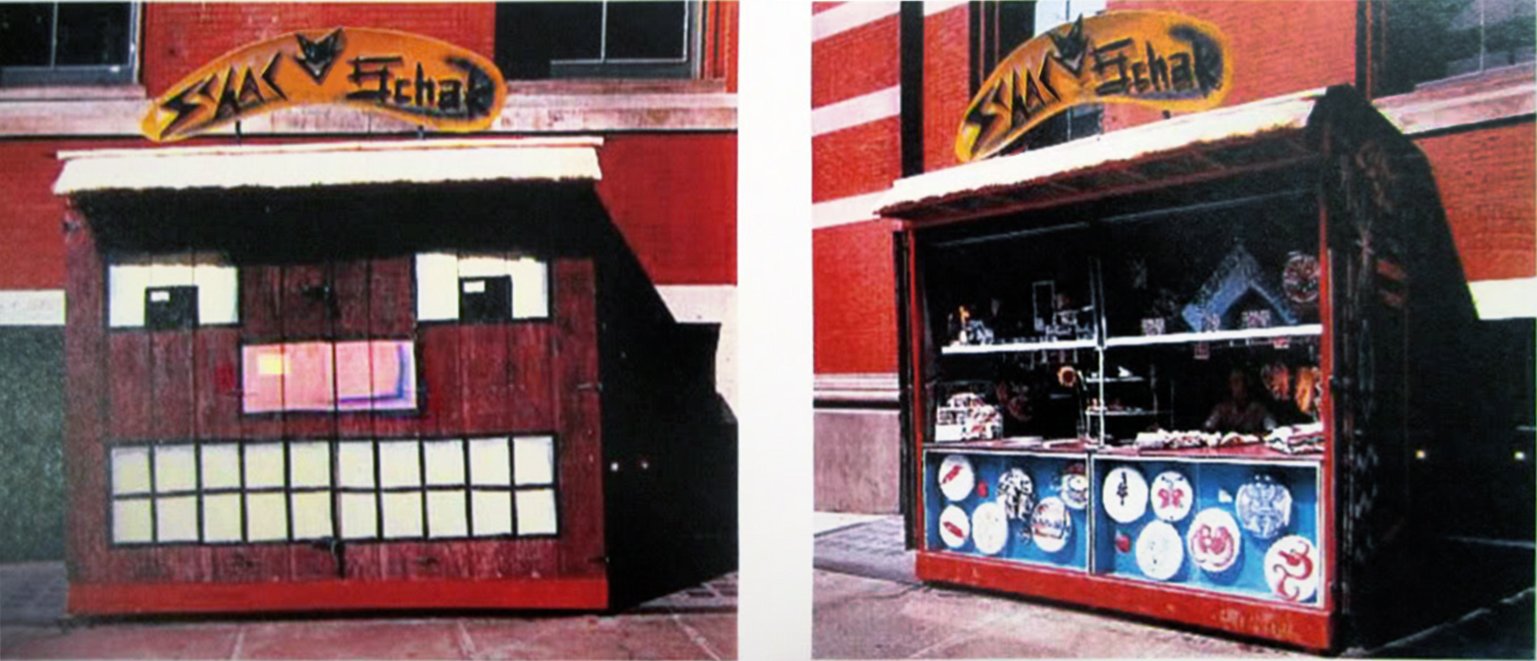

Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Not Much of a Schach Fan

Back to cars, not for the last time, there were Peter Cain’s not-just-for-boys, distorted “autoerotic” paintings (the words of Klaus Kertess per the Matthew Marks press release) whose life was tragically cut short at the age of 37 in 1997 from a cerebral hemorrhage, completing just more than 60 paintings. Peter’s paintings resemble surrealistically foreshortened vehicles recalling Gabriel Orozco’s 1993 sliced and diced Citroen. Matthew’s unerring support and loyalty for artists like Cain and Michel Majerus (who died too young in a plane crash) is admirable.

Then there was Kreps’s dinner. I was seated next to an art star—not Oscar Murillo but of his generation—and a member of the same stable. They turned to me upon being introduced, told me how much they loved my work, and asked if I was still making art, which I affirmed: I’ve been illustrating my articles. I was tickled.

After about 30 minutes into it, it became clear that they thought I was the artist Kenny Scharf. Well I’m used to it, for much of the first two years of marriage, my mother-in-law thought the same. On occasion, the other Kenny has been mistaken for me too.

Thea Westreich* rocked up to our table and barged into the convo I was having, literally pushing me out of the way in her haste to get to the unnamed artist I was speaking with to which the artist responded about yours truly (mistaking me for Scharf): “Wait, he’s a very important historical figure.”

Just off her book tour, fittingly enough titled: Collecting Art for Love, Money and More, and exhibit of her collection at the Pompidou, Le Collection Thea Westreich Wagner et Ethan Wagner, as if suffering from Tourette’s, Westreich blurted out: “I don’t care who he is.” Nice, guess she’s not much of a Scharf, or Schach, fan.

My friendly neighbor confided their distaste for the Murillo exhibition presently on view at David Zwirner and, admittedly, I was generally of the same opinion. Though Oscar is a terribly nice and ambitious artist, the paintings resembled Sigmar Polke albeit with political baggage attached.

We agreed on Matthew Barney’s outstanding (re)outing, though this friend hated the little cast sucrose pea-shaped capsules as much as I liked them; neither of us had too rational a reason as to why.

The next day, I got an email from the friend asking for my tax lawyer—how artists’s concerns have shifted over the years.

Neil Jenny, Vexation and Rapture (1969). Courtesy of Neil Jenny.

Neil Jenney and My Art History Tutorial Via Business Card

Aside from being an innovator of the school of good bad painting, Neil Jenney was an assistant to Paul Thek in the early 60s, and donated Hippopotamus Poison from the 1965 Technological Reliquary Series to MoMA (in honor of Thek’s friend Ann Wilson).

I must say, the work is a masterpiece, and the donation was one of touching generosity. Wow, I am in awe of them both. Inside Jenney’s football-pitch-sized Soho floor-through, a loft he’s owned since 1973, I was given free reign to wander, and I did. From the famed works of the late 60s pitting dichotomous pairs of words and images together—such as “beast” and “burden,” “dog” and “food,” “crash” and “witness” to the atmosphere paintings and his more recent work, it was extraordinary.

Jenney doesn’t travel but knows I’m from the UK. He grilled me on political issues like Brexit and turn-of-the-century British painters he admires. Every time he asked, I admittedly didn’t know any, he’d reach into his pocket and pull out a business card and proceed to write down the name and hand it to me.

He did this four times, with artists such as Stanhope Forbes, Dod Procter, Frank Bramley, and Joseph Wright of Derby. Taped together, the biz cards make for an interesting art piece—thanks Neil! Looking forward to the next visit. The paintings range according to size from $75,000 to $1.2 million, available at a Gagosian nearest you.

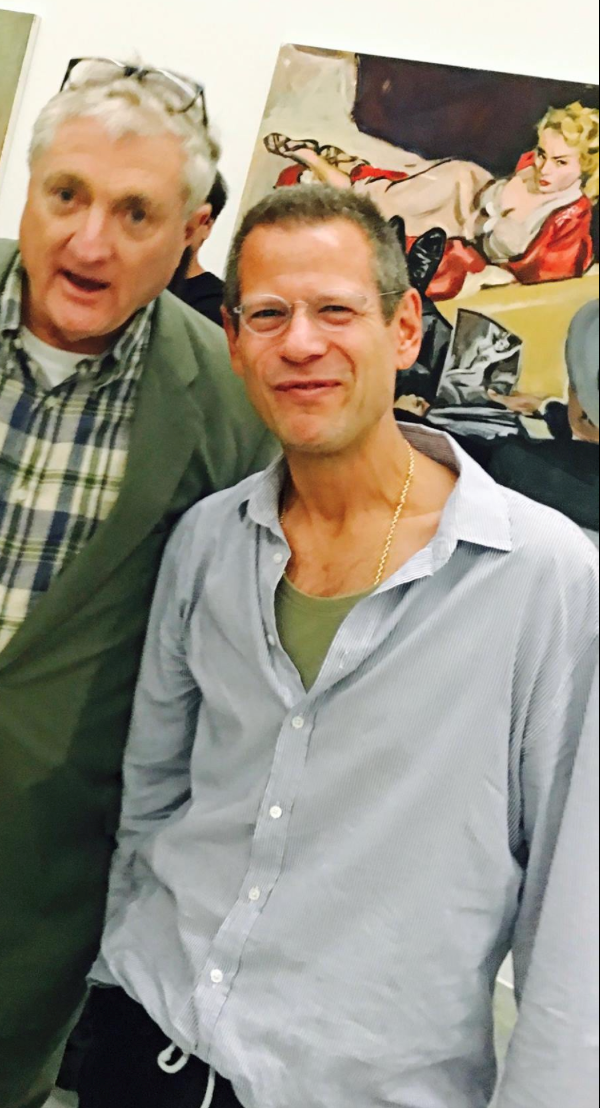

Kenny Schachter, Walter Robinson at his show at Deitch. Courtesy Kenny Schachter.

Road Rage

The Bridge in Sag Harbor is one of the first road racing venues in the US. It operated as a track from 1957 through 1998 and opened as a private golf club by Robert Rubin, a former commodities trader, in 2006, charging $600,000 for a membership. It counted Richard Prince among its founding members.

What better place to host a classic car show coupled with, you guessed it, a Prince show. On hand were my pal Adam (Lindemann), his wife, the acclaimed dealer Amalia Dayan, Bill Powers of Half Gallery with his fashion designer wife, Cynthia Rowley, car collector Howard Lutnick, and former Azzedine Alaïa boutique owner Jacqueline Schnabel. Also there were two of my devious kids, Adrian and Kai (at the School of Visual Arts at present and making art you must see!) and their worse-behaving friends in tow, threatening to twist keys and appropriate one of the three cars owned by Prince that were on view.

I couldn’t blame them; I considered having a go at Adam around the front nine. Meeting Prince was fun, and I was a little star struck (though not quite at the level of a Belieber) and tried talking up cars, to which he replied, “Don’t you write, I really like your writing.” He actually knew who I was. How refreshing (and appreciated).

Getting fired from his previous incarnation as founding editor-in-chief of Artnet Magazine from 1996-2012 (and my editor throughout) was the most fortuitous episode of Walter Robinson’s life and career. In a story as happy as that of Carmen Herrera, Robinson had a knockout retrospective at Jeffrey Deitch’s reclaimed gallery on Wooster. Another late blooming art hero was incarnated, even though my former boss didn’t extend a dinner invite, despite repeated hints.

Kenny Schachter’s collage of Niels Kantor. Courtesy Kenny Schachter.

Pretty Young Things and the Pratfalls of the Market

In a recent story by Bloomberg’s Katya Kazakina that has been ruffling feathers ever since it was published, LA dealer Niels Kantor, who I like and respect, said some rather outrageous things about the upcoming interim auctions, mainly at Phillips, and the formerly hot artists whose works make up, in large part, the auction house’s offerings.

“I feel like it can go to zero,” he said about the work of Hugh Scott Douglas, a talented artist who is all of 28. “It’s like a stock that crashed…I feel like we were a little bit drunk and didn’t think of the consequences, then the bottom fell out. Everyone got stuck with their pants down.”

In the art market, everyone has to have it until they don’t—formerly must-have artists have gone from up there to down there to nowhere. Niels points to his own misfortune while maligning the markets of young artists like a braying donkey. It came off as flippant and vindictive to blame artists for market pratfalls that are utterly outside of their control.

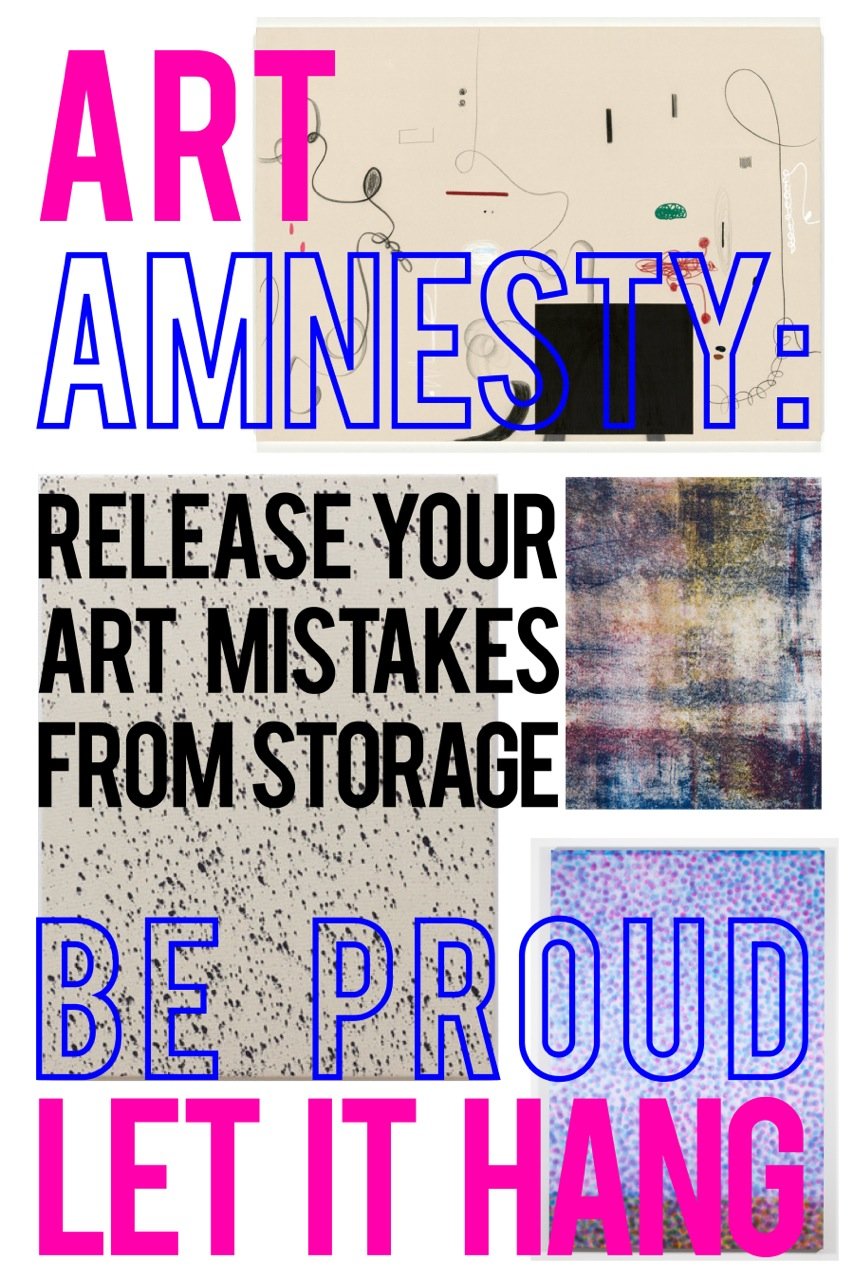

Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Hey, Christian Rosa, Israel Lund, and Lucien Smith. All of these artists have potentially long careers ahead of them and wouldn’t have become lightning rods without a modicum of talent. Not that I didn’t get caught out in the rain too. It’s less unnerving that a handful of very inexperienced, emerging artists lost the lion’s share of their auction prices, than a collector/dealer would so brazenly dismiss what he previously supported.

That he doesn’t like some of his art any longer because it lost value makes Niels a sore loser. I Instagrammed and Facebooked my portrait of Kantor as a donkey and he got very, very upset posting jibes about me (and my wife) on the social media sites. Ouch! Eddie Murphy was the talking donkey in the Shrek franchise and he was widely admired. So what’s the big deal?

This whole brouhaha has inspired me to curate the Pump and Dump Show, I will offer art amnesty (like civil programs proffering forgiveness for illegal guns) seeking the release from storage of art mistakes by spec-u-lectors, under the mantra be proud, be loud. Don’t be fearful of sticking to your beliefs despite what the market (i.e. others) consider bloopers. And by all means, let it hang!

I regretted that I didn’t get the opportunity to poop in the Guggenheim’s golden Maurizio Cattelan toilet, but I do have other things dropping soon: an as-yet-unnamed book of collected writings over the past 25 years and the fact that two of my cars are featured in Octane Magazine: a 1971 BMW CSL Alpina and a 1973 Porsche factory RSR that came in fourth at Le Mans in period. Vroom!

*I first met Thea in 1991 when she bought and audiotape I had created from a hit-and-run group show I had also curated called Unlearning. The tape consisted of the sounds of the brakes of a garbage truck, which squealed like mastodons and the hydraulic starting system of buses in New York City. I thought I was launched as an artist, which turned out to be not entirely the case.