Key Points:

• The onshoring process is designed to preserve the status quo as much as possible, and only permits changes to be made to legislation and regulation when a “deficiency” arises.

• While some deficiencies are straightforward to resolve, some result in “inoperabilities” in retained legislation, and so the government and the regulators must choose a path forward, resulting in potentially significant changes for firms.

• Certain consequential changes may also have an important practical impact.

• In relation to MiFID II, the key inoperabilities arise in relation to the transparency regime, and so measures are being introduced to allow the FCA flexibility over how it operates aspects of this regime, both immediately following Brexit and in the longer term.

• Firms need to be prepared for the impact this could have on their business — although transitional relief will be granted in some areas, certain changes will take effect upon Brexit.

In order to read and understand the publications being issued by the government and the regulators, it is helpful to have an understanding of the onshoring process. This Client Alert provides some general background on the fundamentals of the process, before looking in detail at the key impacts of the onshoring plans for the MiFID II regime. While the practical impact of these changes may take time to assess, market participants are encouraged to respond to the FCA’s consultation on changes to its Handbook and to technical standards, highlighting any potential compliance challenges, by 7 December 2018.

The process of “onshoring”

An important observation to make at the outset is that the plans for onshoring have been prepared on the assumption that there is a “no deal” Brexit — that is, that the UK leaves the EU on 29 March 2019 with no agreed deal in place, and no transitional period. Therefore, these plans will be adjusted accordingly if a deal is struck.

In this context, the aim of the government and the regulators is to maintain the status quo as much as possible from exit day, to have a functioning legal framework, and to mitigate the legislative impact of any “cliff edge” effects.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (the EUWA) essentially will preserve EU law in the UK as it stands immediately prior to exit. It does this by retaining UK legislation that implements EU Directives, and incorporating EU Regulations (which at present are directly applicable in the UK without needing to be implemented) into UK law. The EUWA only onshores operative provisions and so will not incorporate recitals into UK legislation.

As some parts of EU law simply will not work when the UK is no longer a member of the EU, the EUWA includes a limited and temporary power for the government to use a simplified legislative process to “correct deficiencies” in retained EU legislation that result from the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. For example, references to tasks to be performed by the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) such as ESMA will no longer be appropriate and will need to be replaced with references to the relevant UK authority assuming the task in question. The EUWA does not include powers to amend legislation in a manner other than to correct a deficiency, or if a perceived deficiency does not arise as a result of Brexit.

Consequently, it is important to recognise that the powers being used by the government to conduct the onshoring exercise are limited in nature and should not introduce new policy decisions. Any policy changes must be realised using the usual legislative procedures, and likely will be delayed until postBrexit when there is more time to consider and consult on policy decisions.

In order to correct deficiencies, HM Treasury is preparing a series of Brexit statutory instruments, setting out amendments to retained EU legislation. Many of the amendments being proposed are purely technical in nature. There are, however, some areas in which a technical amendment has a significant practical impact, or a lack of operability post-Brexit has led to a particular choice in which several viable options are available. These will be of particular interest to market participants.

Division of labour

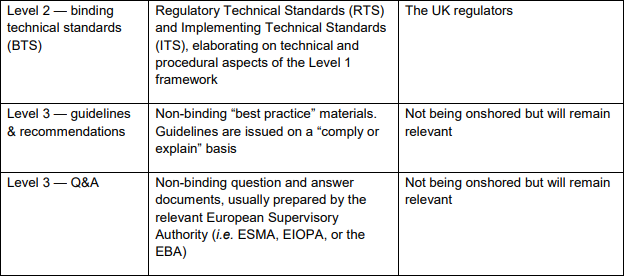

As EU financial services legislation takes the form of so-called Level 1 and Level 2 measures (see summary table, below), and is implemented in the UK through various means when implementation is required (for example, provisions of a Directive may be implemented in primary legislation, secondary legislation, or in the regulators’ rulebooks), onshoring is a complex exercise. Therefore, HM Treasury is delegating some of its powers of amendment under the EUWA to the UK financial services regulators.

The Financial Regulators’ Powers (Technical Standards etc.) (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2018 delegate powers to the Bank of England, PRA, FCA, and Payment Systems Regulator both to amend deficiencies in binding technical standards (BTS) being onshored under the EUWA, and to amend deficiencies in provisions within their rulebooks that implement EU requirements. The rationale is that the regulators are best placed to identify and correct deficiencies in these materials.

The powers of the regulators are limited in the same way as HM Treasury, so they can only use their delegated powers to correct deficiencies arising from Brexit. Additionally, the changes are subject to approval by HM Treasury. The regulators will have powers to amend BTS more generally from exit day, if this is in line with their statutory objectives.

The FCA and the PRA are at present consulting on a first batch of amendments to the FCA Handbook, PRA Rulebook, and relevant BTS. These consultations principally address amendments to regulatory rules and BTS that relate to statutory instruments under the EUWA that have already been published by the government, and are based on the rules as they stood at 1 July 2018. While technically the regulators are not required to consult when using the delegated EUWA powers, they have chosen to do so, to help inform the changes being made. However, these consultations are not subject to the usual rules governing the consultation process, and so, for example, no cost-benefit analysis is required. The regulators are not consulting on changes to forms or reporting and disclosure templates at this stage, as they recognise that it could be very costly for firms to adapt. However, firms are expected to interpret these in light of Brexit; for example, the PRA has produced a draft Supervisory Statement outlining how firms should approach reporting and disclosure fields or definitions that relate to the EU.

General approach

The default position in the onshoring process is to treat EU Member States as third countries. HM Treasury and the regulators make exceptions to this in appropriate situations — largely if doing so could cause financial stability risks or place an undue burden on firms. Also in light of this assumption, a number of BTS that are considered no longer relevant will be repealed. For example, BTS dealing with the exchange of information between supervisory authorities will be repealed as it is assumed that the regulators will not continue to cooperate and exchange information with other EEA regulators in the same manner as they do now post-Brexit.

What about Level 3 measures?

Level 3 measures such as guidelines and Q&A are not saved by the EUWA (as they are not legislation). The regulators are consulting on similar statements outlining their approach to Level 3 measures. The general approach is that firms will be expected to comply with existing guidelines and recommendations as they did before exit day (and the regulators’ approach to non-compliance with particular guidelines, such as the scope of the bonus cap in the guidelines on remuneration under CRD IV, will continue). The regulators will not do a line-by-line review of all existing Level 3 material, and so firms will be expected to take a purposive and sensible approach to interpretation (for example, reading references to ESMA as references to the FCA). Guidance will be updated accordingly in due course if policy changes are made and the expectations in relation to any Level 3 measures alter. The regulators will consider new or updated Level 3 produced by the ESAs post-exit, and will update expectations accordingly.

Transition

The regulators have stated that, for the most part, they do not expect firms to act now to prepare for changes potentially taking place on 29 March 2019, on the basis that it is proposed that transitional arrangements will be put in place.

The EUWA allows the government to make transitional provision in connection with changes being made by the onshoring process. In addition to providing for the temporary permissions regime, HM Treasury plans to give a temporary transitional power to the UK regulators, to allow them to modify or waive requirements if these have changed as a result of onshoring and transition has not been legislated for in the relevant statutory instrument. The powers may also be used to grant transitional relief where existing provisions that have not changed begin to apply to a particular type of firm for the first time. These transitional powers are likely to be used widely in relation to the temporary permissions regime, but will also be important for UK firms.

HM Treasury plans to adapt and expand the existing waiver and modification regime for this purpose, and the special powers would be available to the regulators for two years from exit. HM Treasury is proposing that these powers could be used in relation to any requirements for which the regulators are responsible for supervising compliance, including rules, BTS, onshored EU legislation, and UK primary and secondary legislation. To smooth the process, transitional relief could be granted to entire classes of firms, and firms would not need to apply for the relief as the regulators plan to issue directions setting out the terms.

The general approach proposed by the regulators is to exercise the transitional powers widely to delay the application of onshoring changes that would otherwise result in firms needing to take action before exit day to comply with them. However, delayed application of onshoring changes is not being considered where this would not require specific action by firms (e.g. where changes are technical or only affect the regulator).

Consequently, it is important to read all of the onshoring changes in light of these plans, as it may well be that changes being proposed will be phased in and will not take effect from exit day. That said, the detail of these powers and confirmation of areas in which transitional relief will be granted are still awaited.

Key impacts of the onshoring exercise for the MiFID II regime

HM Treasury has published a draft MiFID Brexit statutory instrument, which will amend UK primary and secondary legislation that implements the MiFID II Directive and Level 2 Delegated Directive, and will amend the retained versions of MiFIR and the Level 2 Delegated Regulations (the MiFID Brexit SI).

The FCA and the PRA are responsible for amending and maintaining MiFID-related provisions in the FCA Handbook and PRA Rulebook, as well as existing MiFID BTS that will be incorporated into UK law by the EUWA, so that they function effectively after exit day.

On 10 October the FCA published its first Consultation Paper (CP18/28) setting out its proposed changes to the Handbook and certain BTS as a result of Brexit. This consultation principally addresses amendments to the Handbook and BTS that relate to those statutory instruments made under the EUWA that have already been published by the government, and therefore covers changes to most of the MiFID II BTS (although it notes that some are still under discussion).

Whilst the resulting volume of changes to the MiFID regime is high, many of these changes are consequential in nature or are minor amendments. There are, however, a number of areas in which the changes are more significant, which are summarised below.

Transparency

Some of the most significant changes to the MiFID II provisions that will result from the onshoring process, both in the short and long term, relate to the transparency regime.

In particular, the transparency regime is currently underpinned by a number of functions (including the performance of various calculations) that are undertaken by ESMA. In a hard Brexit scenario, ESMA would cease to perform these functions for the UK, and they will instead be onshored and assigned to the FCA. This is a significant operational exercise that is likely to take a number of years to put into effect. Consequently, the MiFID Brexit SI includes a number of temporary powers that the FCA will have as a ‘fix’ during a transitional period of up to four years to ensure that the transparency regime operates effectively during this period. The FCA will be required to prepare and issue a statement of policy in relation to its exercise of these powers.

In addition, merely following the baseline onshoring approach in relation to the transparency regime (for example, moving from an EU to a UK-only data set) could result in a number of deficiencies in relation to the operation of the regime. This is not unexpected given that the MiFID II transparency regime was designed to work across all Member States, and was never designed to operate in one jurisdiction alone. This is exacerbated by the fact that, in the no-deal scenario on which the MiFID Brexit SI is based, the UK will not have any oversight of how the EU intends to adjust the existing transparency regime in light of Brexit, and therefore the potential misalignment and arbitrage risks that could arise. Accordingly, the changes to the regime are intended to provide the FCA with flexibility to respond to these risks as they arise.

Pre- and post-trade transparency

During the transitional period, the FCA will have the power to suspend the pre-trade transparency requirements for trading venues in relation to non-equity instruments for a specified period, having regard to the most recent pre-exit thresholds under RTS 2 and any other relevant information in relation to liquidity in the relevant financial instrument, whether in the UK or any other country. This will give the FCA the ability to respond to EU suspensions, as well as introduce any new suspensions that it considers appropriate.

In the long term, the FCA will be able to direct the geographical scope for calculating the liquidity threshold, provided that the FCA is able to obtain sufficient reliable trading data to enable it to assess the volume of trading in relevant financial instruments in a particular country or region. This power will enable the FCA to take into account trading data from countries other than the UK, in order to ensure that the liquidity threshold is appropriate for the UK, whilst also considering alignment with other relevant markets.

Equivalent changes will also be made in respect of the post-trade transparency requirements for trading venues and for investment firms in relation to non-equity instruments.

Systematic internalisers

Threshold calculations

The FCA will be given powers during the transitional period to publish data required for UK firms to perform the systematic internaliser (SI) threshold calculations. If the FCA has not published this data, firms must use the most recent data published by ESMA prior to exit day. Where such data is not available (for example, because an instrument has traded for the first time on a UK venue post-exit), firms will not be required to perform the calculations and therefore will not fall within the definition of an SI.

In the long term, the FCA will be given powers to direct the geographical scope of data used for SI calculations in the UK, provided that the FCA is able to obtain sufficient reliable trading data to enable it to assess the volume of trading in relevant financial instruments in a particular country or region. This will help the FCA to ensure that the SI thresholds are appropriate in the UK, whilst also considering alignment with other relevant markets.

The double volume cap

The requirement for the FCA to introduce new suspensions under the double volume cap (DVC) will be disapplied during the transitional period, so that no new suspensions will be triggered automatically. Preexisting suspensions (in place prior to exit day) will continue in effect until expiry of the usual six-month period. ESMA’s current obligations to publish certain trading data relevant to the DVC will not pass to the FCA during this period, to allow the FCA time to prepare to assume this role.

During the transitional period, the FCA will have a new power to introduce new suspensions of up to six months (the FCA will also be able to renew such suspensions where it considers that the conditions that led it to impose a suspension continue to exist). This will give the FCA the ability to respond to new EU DVC suspensions, as well as introduce any new suspensions that it considers appropriate. For these purposes, the FCA will have the ability to take into account trading volumes in any third country, not just within the EU.

In the long term, the FCA will be given powers to direct the geographical scope of the DVC in the UK (in terms of the trading data it is based upon), provided that the FCA is able to obtain sufficient reliable trading data to enable it to assess the volume of trading in relevant financial instruments in a particular country or region. This will give the FCA flexibility to determine an appropriate scope for the DVC. When the obligations to publish relevant trading data do pass to the FCA, the FCA will be given 10 working days (rather than ESMA’s five) to publish the information.

Transaction reporting

There is a key departure from the baseline onshoring approach in this area, as the current scope of reporting (EEA and UK) will be retained. This means that UK firms will need to continue to submit transaction reports to the FCA in relation to trades in financial instruments admitted to trading, or traded, on trading venues in the UK and in the EEA.

There will, however, be a change in approach in relation to UK branches of EEA firms. UK branches of EEA firms currently send transaction reports to their home state regulator, and the transaction report is then shared with the relevant host state competent authority. The MiFID Brexit SI is, however, drafted on the assumption that the FCA will no longer have access to this information, and therefore requires UK branches of EEA firms to transaction report to the FCA in the same way as UK branches of non-EEA firms. UK branches of EEA firms will therefore potentially be subject to a double reporting requirement in some cases, and will need to adapt their reporting systems to facilitate transaction reporting to the FCA.

In addition, UK trading venues will have to report transactions on their venue by EEA firms, as EEA firms will become third-country firms and will not have an obligation to report to the FCA. UK trading venues will not need to report for UK branches of EEA firms (which will be required to submit their own transaction reports to the FCA). UK trading venues will therefore need to distinguish trading by a UK branch from trading by an EEA entity when the branch is not executing.

The FCA will also become responsible for maintaining a UK FIRDs database, which may well take some time to establish.

Mandatory trading obligation

In order to comply with the UK share and derivatives trading obligations post-exit, firms trading shares and derivatives subject to the UK trading obligation will need to do so on:

• A UK regulated market;

• A UK MTF;

• A systematic internaliser meeting the UK-specific definition set out in the MiFID Brexit SI; or

• A third country trading venue assessed as equivalent by the European Commission prior to exit, or by HM Treasury post-exit.

Accordingly, whether firms can rely on EEA venues to satisfy the UK trading obligation will depend on whether, and how quickly, HM Treasury makes an equivalence decision in this regard post-exit. The MiFID Brexit SI does not address the potential conflict that would arise in the event that an instrument is subject to both the UK and the EU mandatory trading obligations. Given the general approach to Level 3 measures mentioned above, and subject to any contrary indication, it would be fair for firms to assume at this stage that the FCA intends to continue with ESMA’s approach to the scope of application of the mandatory trading obligation for shares.

Commodities — Ancillary Activities Exemption

The ancillary activities exemption for firms trading commodity derivatives is another key area in which there has been a departure from the baseline onshoring approach. In order to be able to rely on the exemption, firms must satisfy both an internal and external test and, currently (pre-exit), the external test compares the size of a person’s trading activity against the overall trading activity in the EU on an asset class basis to determine that person’s market share. Following the baseline onshoring approach would change the basis of this external calculation to a UK-only scope. RTS 20 will, however, be onshored to maintain the EU plus UK scope (i.e. both the numerator and the denominator for the external calculation will continue to be based on EU plus UK market data), therefore maintaining the current scope of the exemption.

Temporary permissions

The MiFID Brexit SI introduces specific provisions for EEA firms that intend to take advantage of the temporary permissions regime. The detail regarding the operation of the temporary permissions regime more broadly has been set out by the FCA and the PRA in their consultations (CP18/29 and CP26/18, respectively).

The MiFID Brexit SI introduces the concept of “substituted compliance” for firms with temporary permissions. This means that if a firm within the regime complies with a requirement in MiFIR (as it applies in the EEA), provided that requirement has equivalent effect to the corresponding requirement in the UK onshored version of MiFIR, the firm is to be treated as complying with the UK requirement. However, substituted compliance is disapplied in relation to various requirements. This includes, for example, the mandatory trading obligation and transaction reporting requirements