My father always calls to tell me about the weather. October in California is wind and heat; fires rage, and he says that California is falling into the ocean. He says the smoke and smog-filled air makes him feel trapped and heavy. I say I understand this feeling, even in New York City where the beginning of fall feels crisp, where I live far away from him. The air is clean here, I say.

This time my father rushes over the weather. He tells me my grandfather has died and that he’ll bury him at sea. My father says he’s at peace; I’m not sure if he’s talking about himself or his father, and I wonder how all these generations of abuse and alcohol could leave anyone content.

I can hear it in his voice — his agitation to get off the phone, to not listen to me. My father will vanish. I just know that fire inside him cannot be put out this time. He always runs wild; he leaves when things are too dark, too unbearable; he’ll hide for a while on a bender; he won’t be my father.

He tells me not to fly home, to keep on working and living, that my grandfather wouldn’t want it any other way. He reveals he’ll get a little bit of money so he can move into a studio right on the sand. He’s happy, he says; he’s back with his friends, he’s got to go because the game is on, tells me there’s nothing like California in October, and then everything goes silent.

The first time I went whale watching, I was 8 years old and my father was supposed to chaperone the trip. He bailed that morning; I can’t remember the excuse. He said to look up from the school bus into his apartment window for a surprise on the ride in. The bus crept down the Balboa Peninsula, and there in the window of his apartment above the butcher shop was a sign made of computer paper and purple marker. Big block letters read: “HI CRIS.” When we passed I kept quiet, and by the time we filed onto the boat, everyone had forgotten I even had a father. We inched out of the harbor, past the lazy seals on the big red buoy, and we hit open water. A California gray whale appeared, and nothing else mattered: Her skin was tough and sleek; she was a creature full of life and wonder. That night I was still rocking in my bed. My dad called to ask how it went; I was angry and seasick and didn’t tell him about the whale. Instead, I dreamed of that whale all night and for the rest of my life.

New York is too cold for me in November. I take a million showers a day to try to warm my toes with hot water. My face is red and chapped; I don’t know how to treat this. The leaves have fallen, and that is something I never expected; the trees are bare, and I think they are dead. I can’t imagine how these barren trees could someday come back to life.

My father texts me on Thanksgiving: “Hope you’re not freezing.” He sends a blurry photo of the ocean view from the bar. I try calling, but he doesn’t pick up. I try again the next day and the day after. He’s a ghost. He’s using and drinking, I know it, but I tell myself he’s grieving his own father — but I tell myself a lot of things. The Los Angeles Times reports more fires, more smoke, more epic sunsets, perfect waves, and south swells. My feet are frozen; my father is basking in the cruel sunshine of late fall. I call him again, I miss his voice, and he doesn’t answer.

New York at Christmas is full of old, dirty snow — something I hadn’t anticipated after the glee of watching the season’s first snow, my first snow, fall from the sky. I’m not sure winter is beautiful anymore. I want to tell my father, but he’s not answering the phone. I want to tell him the bitter cold is worse in the wind, that my face is so red here, that my hair has taken on a new genetic makeup: full of static and strangely featherlight. I want to tell him that though I have not figured out how to keep my hands and feet warm, the lights are glittery and perfect, all the warm food is delicious, and my life is taking shape. Still, he doesn’t answer.

California at Christmas is cool, quiet without tourists and traffic, and sunny. I check the weather, I miss home, I miss my father, and I don’t really miss any of it either. I keep going. I guess we’ve done this before; I know this man. I know there’s nothing I can do. Except I wonder all night and all day, What can I do? I text and text, and finally he texts back, “Merry xmas baby I love you.” I call and call. The snow is so silent.

One Christmas morning, my father and I ate warm donuts on the seawall and watched the surf. He quizzed me on the rip current, made me point it out. I didn’t want the cream inside my donut, so I bit the top and squeezed out the goo like a toothpaste tube. I covered the mess with sand. My father scolded me: “Now some idiot is going to step in it!” We dug for sand crabs. When we were walking back up to the parking lot, I grabbed my towel on the seawall and stepped right in the donut goo. My father lovingly called me an idiot for the rest of the day. We laughed about it for years.

We have agreed that the weather is extreme; we text back and forth about the Arctic blast on the East Coast and the burning forever summer in the West. He won’t answer my calls though; when I’m drunk in January, frozen to my core, I leave him a voicemail: “Why are you killing me? Please call me back. Please.”

The heater breaks in my apartment; I sleep in all my clothes. The heater is fixed; it cranks and is too hot, and I sleep in my bikinis. My father calls back a few days later. I hear his voice. He sounds like himself, only different — like he’s been on a bender, like he’s never coming back. I want to cry and scream. I want to tell him I love him, except we are so good at the silence and talking about other people’s weather. I’m smoking a cigarette out my bathroom window, my hand freezing under the falling snow.

He tells me he has cancer.

I slink down into the bathtub and cry right into the phone. He cries too. He tells me an elaborate story that doesn’t make sense. He’s lied before, but never like this. But the cancer doesn’t add up, and he says he needs my help. I tell him I’ll move home, I’ll take care of him. I’ll leave my job and get a new one. He says, “No, baby. I just need five-thousand dollars.”

My father has always said he was sick. Of course he was probably just hungover — or, worse, defeated and hungover — and over the years I stopped believing him. There were bouts of seizures, broken bones, bloody fists, and a long period when he missed a few weeks of phone calls because he said he had to have his gallbladder removed. I never knew what was real, which lies were just excuses, which truths I needed to believe. In some ways, I was always waiting for him to die. In some ways, I was dying too.

“I can get the money,” I say.

When I was 10, I went to Santa Catalina Island with a friend and her family. We spent the day swimming and eating saltwater taffy. The adults let us roam around while they sat steady at the bar, our boat moored in Avalon Harbor. By the time we left, it was late. We were tired and slept in the small bed in the little cabin below deck. Halfway through the trip, I woke up, my stomach in knots, and let out all the pink and blue taffy from my insides right onto the bed. My friend’s mom helped me to the bow, where I let it all go, again and again. The men were drunk. I knew the sounds of their voices, the sway of their feet, their smell — drunk men were all the same. We edged back along the coast and finally one of them admitted it: “We are lost.” In between vomiting, I navigated us all the way home by memory. I knew the lights, I counted the piers; I knew my own harbor’s mouth by heart. When we got back to land, hours after promised, my father was not there to pick me up. Later, I wanted to tell him everything. But I’m sure I didn’t.

He goes missing again. No texts. No calls. The only updates I get are through my grandmother about his “treatment.” Radiation, I think. I text him that I want to speak to his doctor, that I want to help, and he must know I know. We’ve been dancing around it forever; his shame becomes worse when I can see through him. He’s lied to me and taken my money. It is the quietest moment in our relationship, a shame I know he’ll never come back from. I send him a photo of me standing in a foot of snow. He texts back a fiery sunset. I tell myself this is the only way he can keep talking to me, the only way he can bear me.

I was 6 the first time we drove to Big Sur, and it was then I saw my father light up. This was his place. We pulled off the coast for homemade sandwiches. He cracked open a beer on the beach; we fished, caught nothing, and then parked at the top of Ragged Point. We walked out so close to the edge; we peered over the steep, rough cliffs, so afraid of great heights. He swept me up and said, “This is where dads take their bad daughters”; he pretended to throw me over. My father —his silliness, his terrifying humor was deeply funny. He swept me back up, away from the edge, and held me close. “I got you.”

In New York I have springtime allergies. They are so different from my allergies in California. I’m still wearing a coat when the trees come back to life. I’m still cold when the allergist tells me that I’m highly allergic to New England tree pollen. I send a picture of my swollen eyes to my dad. He says, “See, you should just come home.” I know he doesn't mean that. I know he never wants to see me again. I think, Come home to what? He says he’s feeling so good that he’s been swimming in the sea again. That he’s just never been happier. He feels bad for how terrible things were for us these past few months, but he was just sick. And he’s getting better now. This sounds like my father when he’s sober, or trying to be.

I don’t ask for the money back. I don’t ask for anything.

We stop calling each other because our own voices are intolerable. The sound of all the shame is deafening. He ends every text with “ILY.”

My father used to parade me around, his little daughter, at all the beach parties. He tried to be careful that I didn’t see the drugs, but I did, and he tried to be careful not to do them in front of me. He was careful to stay sober enough when we were together. He rented an apartment with a pool. A pool! I’d spend hours flopping around like a fish. He’d pull me around by a pool noodle, he’d lie in the sun, we’d listen to music. The apartment complex was a constant party. When the sun went down, I’d be exhausted and full. I’d sleep right next to my father, and the next day we’d do it all again.

Suddenly, as if there were no such thing as time, New York is humid and warm. The subways gross me out; I hate summer more than I hate winter. Everything feels thawed but unbearable. I am a warm pile of goo.

My father and I text about coming home that June to celebrate my 26th birthday. I don’t tell him that I’m really coming home because I need to see if he’s alive. My father says he wants to throw me a birthday party; he tells me things are so good. It’s hard not to have constant hope that things will get better, because there’s just no other way to live with a person like this. I just have to love him. So he invites everyone he knows, and I do too.

Before the party, I visit my grandmother. She tells me that my father was recently living with her for months, that he’d been kicked out of a few apartments, that she worries about him. I go to work cleaning my grandmother’s kitchen, and then I venture into my father’s room. It’s a total mess, a nightmare of addiction: beer cans everywhere, pill bottles, coke straws under the bed. I stuff trash bags full of everything he’s always tried to hide, and I see where my money went.

I arrive at the bar and a hundred people are there for me. My friends, his friends, the ghosts of our past. He’s happy, and buzzed, and proud to show me off. I cannot look him in the eye. I reveal that I went to his mother’s, that I cleaned out his room. I get blackout drunk and puke in the tiki-themed bathrooms; my father slips out early. It’s the last time I see him alive.

When I was 12, we spent Father’s Day surfing and fishing at Doheny. I was sitting frozen on the beach when, like a wounded, wet dog, my father traipsed back to me, his arm dangling from his wetsuit. I had to take him to urgent care to get his shoulder popped back in the socket. Afterward, my father told the doctor he was also having back trouble. And shoulder trouble. He was so sore. He told us they removed his gallbladder and there was still pain. So they gave him his first real dose of pain pills. He nursed himself to bed with booze and pills, and maybe that was when he went into the sea and never really came back.

In the late summer heat, New York is unbearable. Maybe everything is unbearable. I feel suffocated everywhere I go: underground, above ground, in my second-floor apartment. California is extremely hot, finally; everything is dead there, scorched and ripe for fire. My father has not updated me with any weather, and I don’t ask. My father and I are not speaking since my birthday party, and we are not texting.

The barometer drops, but the pressure is still too much. So I break the silence: “I hate this humidity.” He texts back, “There’s no beach parking. Fires coming early.”

Hesitantly I tell him I’m coming to Los Angeles for work soon. He says he wants to see me, that he’ll make it happen no matter what, that he misses me. Never “sorry” though. Only more about the traffic, the heat, all the congestion. It feels worse than silence.

In August, I go to California for a work trip and I feel relief. Though hot, it’s dry. I know this feeling; this weather, I can navigate. Everything inside me turns; I’m nervous to see my father. I drive down the coast to Newport Beach and stop at our favorite local surf shop. I get him a long-sleeved tee, his favorite, a peace offering of sorts. I am ready to put this behind us, to start talking again, really talking. I just miss him, and I just want to love him. I want to tell him I will be there for him, either way, and I will forgive him. That I know he is ashamed, but I’m not, and I never have been.

He texts that he’ll “be around,” that we can “meet up.” But he never shows. I go to all the bars. I’ll never know where he was hiding. I leave his shirt folded in a brown paper bag with the bartender, drive all the way back to Los Angeles in tears. I work. I cry in my hotel. I fly back to New York. He finally texts me a few days later: “Sorry I missed you, was feeling sick. thx for the shirt baby! See you next time.”

The weather in New York is already changing.

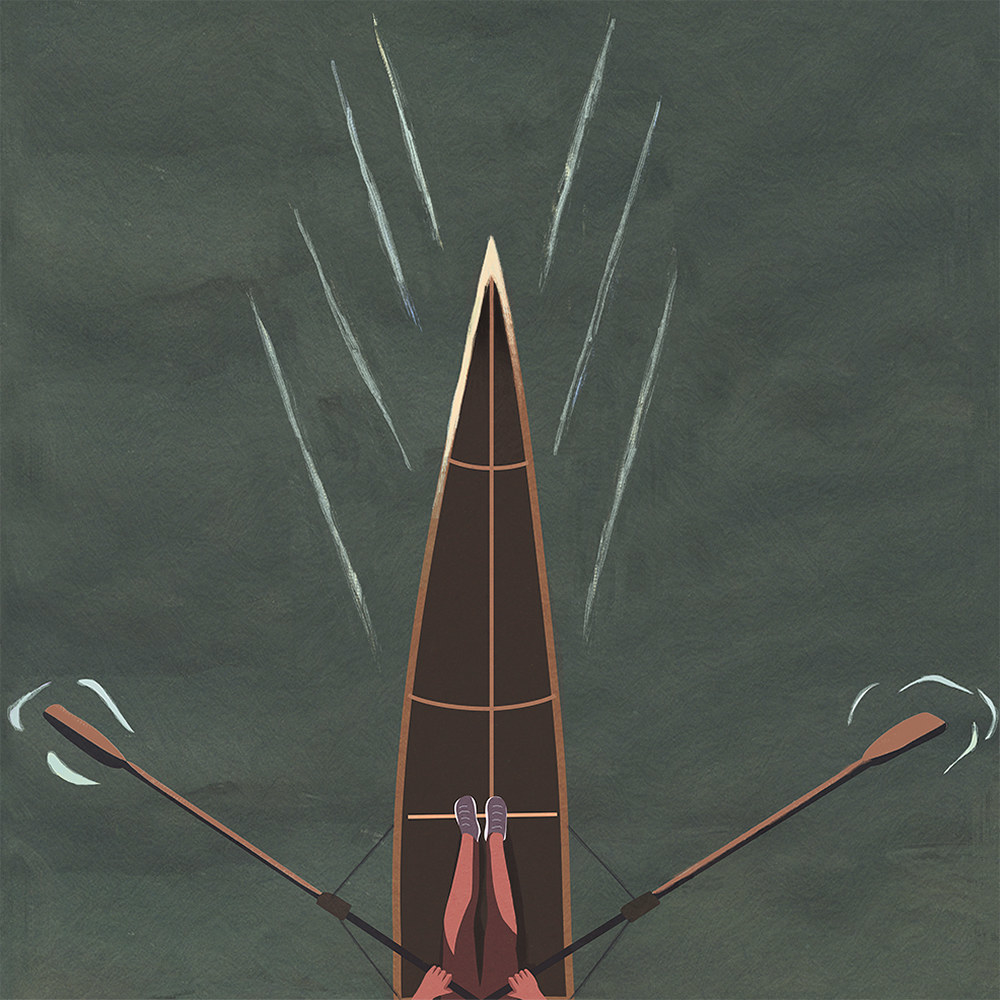

One morning in my first year of college, I was rowing in Newport Harbor before sunrise. It was pitch-black, and my only navigation was the sound of the oars against the hull, the riggers clicking into place, and the coxswain in front of my face speaking softly into a microphone. I dug my oar, and everything was illuminated with phosphorescent green phytoplankton. I kept rowing, digging deep into the glowing sea, and we are floating. My father said if you’re lucky enough to see the sea glow you will die in peace. The sun crept up, and the water was no longer illuminated. My boat started the head race. When we passed under a bridge at the first light of day, I heard my father’s voice from above: Cris, Cris, Cris. I glanced up and he was waving, glowing. I looked for him at the finish line, then at the boathouse; I tried to find him later that day. Maybe everything about him is just a dream.

I spend the very end of summer in Montauk, and I’m happy to leave the city. Montauk feels like home — it looks like California, and it feels like it, but it’s different. It’s slower, quieter. Maybe just as beautiful. In California, the heat is still coming, and the fires, and more heat. I don’t have the courage to text my father — haven’t I tried everything? — and I tell myself I still love him. We aren’t texting. We aren’t anything anymore. I tell myself I like New York in late summer.

Back in the city, I get the call at midnight that my father is dead. I throw open the window for air, and it’s not the air I know. “He died in the early light,” they say. “He’s not coming back,” I say to no one. All those years of guessing which disease would kill him, and it was the most obvious one: He was drunk and fell and smashed his head, bled to death alone. There was no way of guessing how much I could love him and hate him too.

The coroner asks me to list some identifying features. He had a green birthmark on his right temple, he had a varicose vein in his leg, and he had his gallbladder removed. The coroner says, “He most certainly has his gallbladder.”

One night, when I was barely 21 and heartbroken, I texted my dad late. He’d usually be asleep, having spent the day drinking, but this time he answered. Perhaps it was the urgency of my text: “I hate everyone, where are you?” I told him I had to leave a dude’s house, I was stranded on the peninsula, I had nowhere to go. He told me to meet him at his regular bar. It was the first time I drank with my dad. I sobbed into my Jäger shake, and he let me talk. He listened and listened, and he told me I was a fool: “You’re a fool because that guy sucks and you are so much better and you are going to do so many great things and I shouldn’t have to tell you this so stop crying and get it together you’ve got a beautiful life ahead of you because you are you.”

I’m back on the Balboa Peninsula, boarding a boat that looks just like the whale watching boat from my childhood, cruising through the harbor I’ve known so well. I’m carrying my father’s ashes in a plastic bag inside a cheap urn. His remains are oily, heavy; I can see parts of bone. I carry him on my lap. This is the kind of parade he’d want; we pass all the places where we loved each other, hated each other, forgave each other. The boat effortlessly gets us to the mouth of the harbor, past the buoy with the lazy seals, and into open water. When the boat stops, it sways hard. I lean over the edge — it’s all so unceremonious with the boat digging and rocking in and out of the sea — and I dump him in. He’s so much heavier than I think he’ll be. I throw roses. It’s just my uncle and me. We are quiet. Our bodies breathe. Everything up and down. My father starts to dissipate. The ride back is long. Everything is over. We don’t know what to do with the oily, ashy bag and the cheap urn. A pod of common dolphins rides the hull.

I begin without him when the leaves fall from the trees and everything is bare. The air is clean. I can breathe, and the lump in my chest is smaller and smaller. Lives must be full of lost years. This is what I tell myself when I’m back in New York, busying myself with things like work, graduate school, and online dating. I tell myself that my father’s last year was a blink. This was not my father. But this was my father, too.

A few years after my father dies, I take my husband to the Balboa Peninsula. We drive the length of the land before it becomes water. It feels like the end of the world there. We walk along the beach, and I point to where he’s buried. “Out there,” I say. We keep walking, and something tells me to stop. Like I’ve been stung. I stare at the sea, and it’s the calmest I’ve ever seen it, so eerily silent.

Dangerously close to the shore, a seal appears. He bobs right out of the water, almost smiling, and stares at me before falling right back under a small, quiet wave. He comes up a few more times, like he knows me. He’s comically large, like a cartoon sea creature. I yell for my husband in the distance. I can’t stop laughing. Then crying. My husband never sees the animal. We wait for him to come back. He doesn’t. When I wonder if he was ever there, I remind myself that he was always there. ●

Illustrations by Holly Stapleton for BuzzFeed News

Crissy Van Meter is a writer based in Los Angeles. She teaches creative writing at the Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College and is the founder of the literary project Five Quarterly and the managing editor for Nouvella Books. She serves on the board of directors for the literary nonprofit Novelly.

Her debut novel, Creatures, is out now from Algonquin Books.