Staley scrutinised as Barclays faces historic dilemma

Simply sign up to the UK banks myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Antony Jenkins met one of Barclays’ leading investors a few weeks ago, the bank’s former chief executive was quick to point out how dire its share price performance had been since he was ousted in mid-2015. “Not that he’s bitter,” joked the investor.

At the time of Mr Jenkins’ departure, Barclays shares were close to 260p. Since then, hit by the Brexit vote, an investigation into its new chief executive, sluggish investment banking markets and the threat of a big fine by US regulators, the shares have dropped to 190p.

Since the start of this year, the British bank’s share price is down 15 per cent, missing out on a rally across the global banking sector and underperforming its leading rivals.

Several top 20 investors say they are frustrated at waiting for Barclays to start producing the results they were promised in a strategic overhaul presented at the start of last year by Jes Staley, the American who took charge a few months after Mr Jenkins left.

Their biggest source of angst is a question that has tormented Barclays for decades: what to do with its investment bank. Since Barclays toyed with closing down the division 20 years ago under its then chief executive Martin Taylor, it has flip-flopped on strategy in this area.

Under the leadership of Bob Diamond, who oversaw the 2008 takeover of the failed US arm of Lehman Brothers, the investment bank entered the big leagues on Wall Street. But, following Mr Diamond’s exit in 2012, Mr Jenkins spent years trying to shrink the division, only to see much of this now being reversed by Mr Staley.

This strategic conundrum is brought into closer focus as the bank prepares to split in two over the Easter weekend of 2018 — with the British consumer bank on one side and the corporate and investment bank on the other — to meet UK “ringfencing” requirements.

Becoming two separate businesses, each with their own board of directors and funding, creates “interesting choices of where to put the capital and what to do with the strategy,” says a person involved in boardroom discussions at Barclays.

“So far the evidence that Barclays is delivering is scant,” says another top 10 investor. “After the ringfencing, this will become a very live debate as to whether you look to do something strategic with another investment bank.”

To counter the sceptics, Mr Staley has promised to boost the bank’s overall return on tangible equity above 10 per cent for the first time in almost a decade.

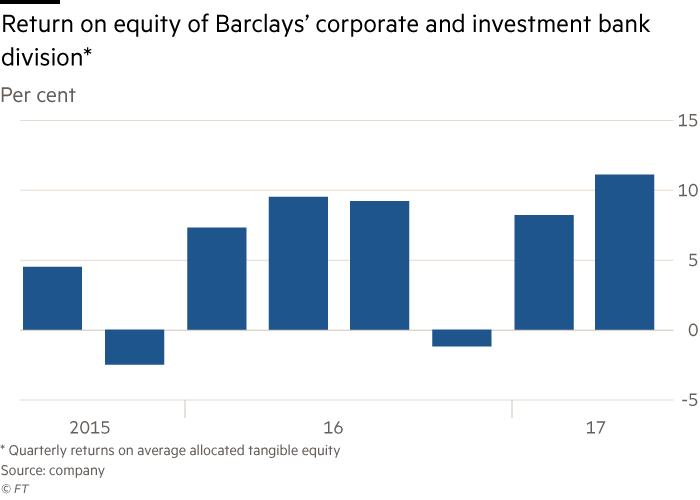

The corporate and investment bank, which absorbs more than half of the group’s capital — was its weakest performer last year with a return of only 6.1 per cent — lagging both the UK consumer business and the international consumer, cards and payments unit.

To break this cycle of value-destruction — which explains why Barclays’ shares are worth only two-thirds of the bank’s book value — Mr Staley is doubling down on the investment bank, betting that he can achieve growth in the unit while keeping costs in check.

For this he has hired several of his former colleagues from JPMorgan Chase, where he used to run the investment bank. Notably, he has put Tim Throsby, the Australian-born former head of equities at JPMorgan, in charge of Barclays’ corporate and investment bank.

Setting out his bullish vision for the first time at a Bank of America conference last month in London, Mr Throsby talked about the need to “re-establish the excellence of years past” at Barclays. He promised to “invest in the business”, “grow revenues”, “inject important new talent” and seize “opportunities to deploy risk of an appropriate scale for our clients”.

He plans to add £50bn of assets to the investment bank’s balance sheet by redeploying capital from low-returning corporate lending business to areas such as fixed income and foreign exchange trading. Mr Throsby wants to lift Barclays’ position in financial market league tables from seventh to sixth.

Analysts say growth will be hard to achieve while fixed income trading revenues are falling 15-20 per cent year-on-year, as is widely expected in the third quarter. Investors question why Barclays doesn’t return excess capital to them, or invest in its higher-return activities. But Mr Staley is betting that the investment banking market will grow in the longer term as companies fund themselves less from bank balance sheets and more from capital markets.

“The investment bank is not big enough to dominate and it is way too big to close,” says Alastair Ryan, analyst at BofA. “Barclays’ strategy isn’t obviously wrong, but we don’t think it will offer an attractive return in the next few years, so naturally there is a debate.”

Other issues are weighing on Barclays’ share price. The bank faces a potential multibillion dollar hit from a civil lawsuit in the US over the alleged mis-selling of mortgage securities before the financial crisis and a criminal case in the UK over the terms of its emergency fundraising from Qatari investors in 2008.

Later this year, UK regulators are expected to publish the results of their investigation into Mr Staley’s attempts to uncover the identity of a whistleblower, for which he has already been censured by his board. If regulators question his character, it could force him to quit and potentially undermine much of the bank’s strategy.

Even if he survives this scrutiny, the jury is still out on whether Mr Staley’s strategy will prove a success. “The investor base feels that too much capital is being tied up in an investment bank that is not generating a high enough return,” says Joseph Dickerson, analyst at Jefferies. “They have maybe two years to prove themselves. It is a limited timeframe.”

Comments