Illustration by Merry Eccles/USA TODAY NETWORK. Photos by Zoe Meyers/The Desert Sun, Getty Images.

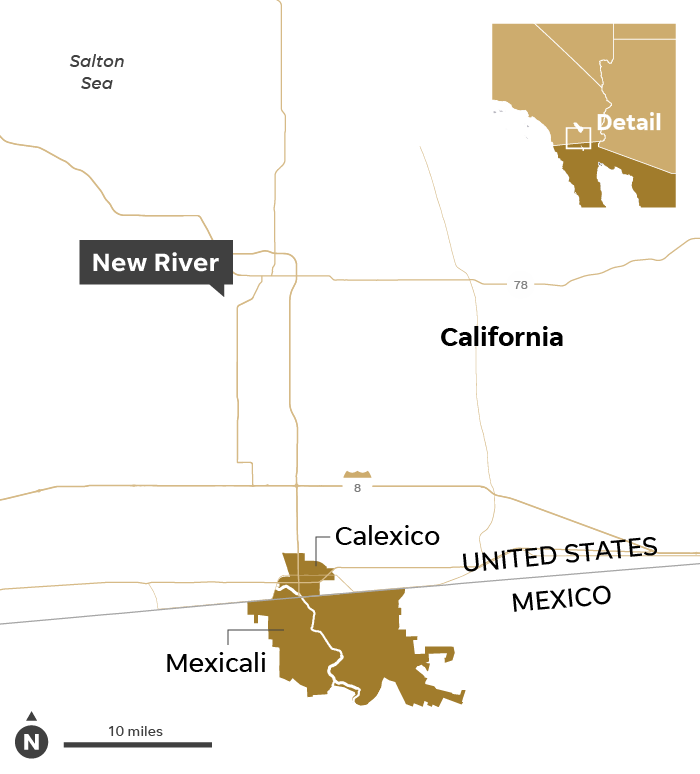

The Río Nuevo flows north from Mexico into the United States, passing through a gap in the border fence.

The murky green water reeks of sewage and carries soapsuds, pieces of trash and a load of toxic chemicals from Mexicali, a city filled with factories that manufacture products from electronics to auto parts.

For people trying to cross illegally into the United States, the river offers a route to try to slip past Border Patrol agents. But the water is so polluted that people who wade in get itchy rashes or sores, and anyone who gets even a splash in the mouth becomes violently ill.

Just north of the border in Calexico, the New River is treated like a toxic waste site. On the edge of its trash-strewn ravine, a yellow sign is planted in the dusty soil with a skull-and-crossbones symbol and the warning: “CONTAMINATED SOIL AND NEW RIVER WATER, KEEP OUT!!”

For people who live next to the river, the odor can be so overpowering that it gives them headaches. Their eyes water and their nasal passages sting. To escape the stench, residents avoid spending time outdoors in their yards.

“All the chemicals, all the waste that comes from the factories there in Mexicali, I can’t tell you what it contains because I don’t know,” said Ernestina Calderón, who lives on a street next to the river in Calexico. “But I’m 100 percent sure that they’re chemicals that are harmful for your health.”

A decade ago, Calderón survived a fight with stomach cancer. Her adult son had cancer in his lymph nodes and survived.

Several of Calderón’s neighbors — she counted six people — have died over the years of different types of cancer, including lung, pancreatic and stomach cancer. Other neighbors suffer from illnesses including asthma and thyroid disorders, which can be triggered or worsened by pollution.

Residents have been complaining for years that living next to the river is making them sick. They’ve demanded government agencies clean up the sewage and industrial waste. Yet despite those calls for help, the river is still filled with high levels of bacteria and toxic chemicals.

In an investigation into the pollution that afflicts the city of Mexicali and nearby border communities, The Desert Sun found that the New River is plagued by harmful chemicals and heavy metals, increasingly frequent sewage spills and a lack of funding to fix those problems — despite recognition among government regulators on both sides of the border that the river requires bigger cleanup efforts.

During the past two decades, the U.S. and Mexican governments have spent more than $91 million on jointly funded upgrades of Mexicali’s sewer system. But the rapid growth of the city, with its proliferating maquiladoras, has outpaced the sewer infrastructure. Spills of raw sewage into the river are on the rise and becoming a major problem, and the wastewater plant that discharges into the New River doesn’t disinfect the water or remove chemicals or heavy metals.

Mexican government agencies are charged with regulating releases of industrial waste from the maquiladoras, and companies are supposed to treat wastewater to meet the country’s standards before discharging it into the sewer system. But the factories face questionable oversight and minimal enforcement. And Mexican government records show companies reported discharging wastewater containing some of the same toxic pollutants that are turning up in water tests in the New River.

Those tests of water and sediment samples by California regulators show the river is one of the most polluted in the state, with high levels of heavy metals including lead, copper and mercury.

There are also toxic chemicals including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and byproducts of the banned pesticide DDT.

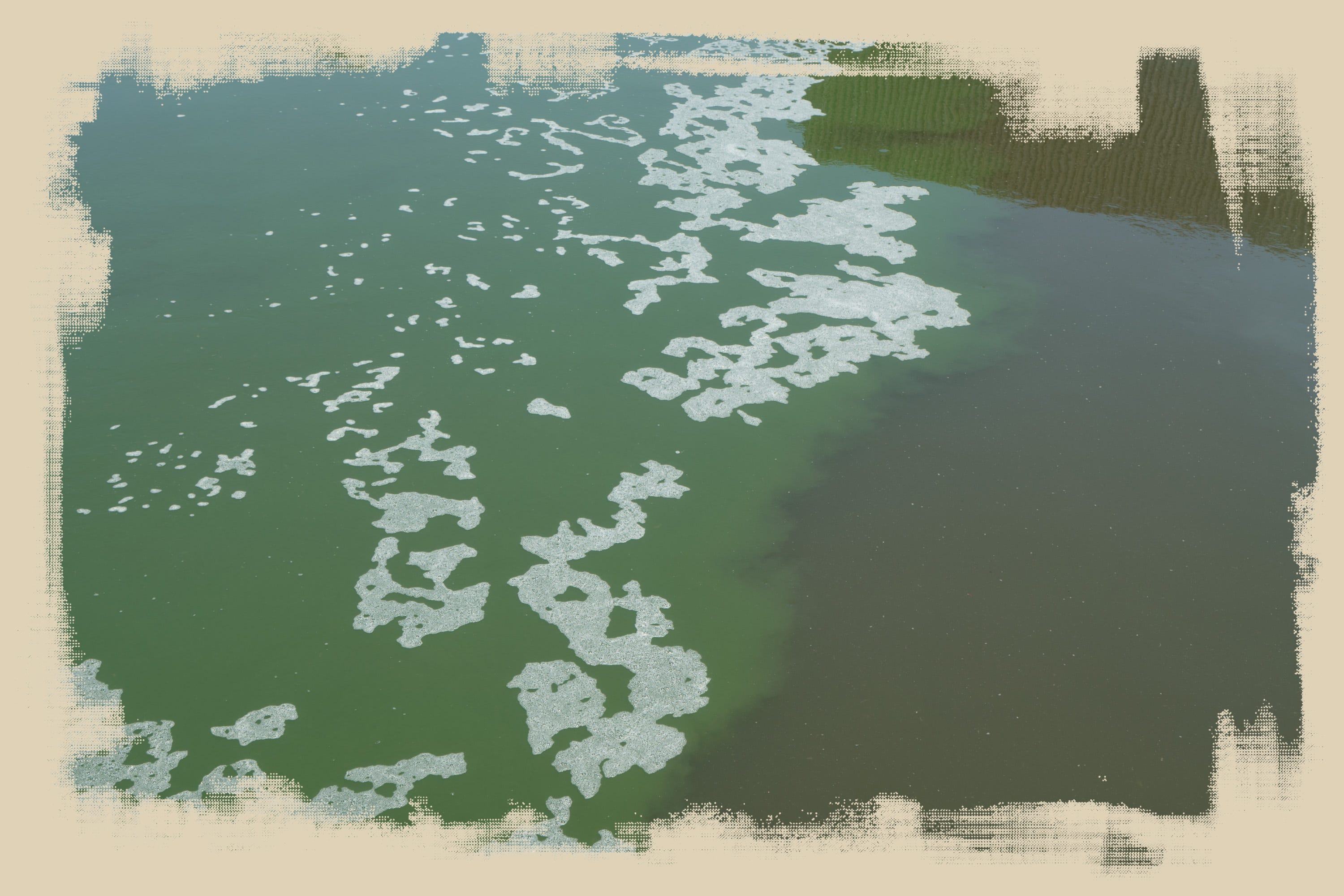

Along the river, there are still signs of life, including egrets and herons that forage on the banks. Yet as Border Patrol agents scan the river looking for migrants, they sometimes see masses of dead fish floating — signs of the dangers in the dark, cloudy water.

An open wound

Calexico Street runs next to the river gully, lined with stucco-walled homes and big lawns.

The neighborhood, called the Nosotros Subdivision, was built in the early 1980s. A black-and-white photo of a groundbreaking ceremony in 1983 shows members of the Calexico City Council smiling with shovels alongside developers from the company Shamrock Properties, one of two companies that were building the first 80 homes.

The caption says the development featured three- and four-bedroom homes selling for $59,000 to $61,000. The subdivision was planned as a low-income housing project and was built with state and federal assistance.

Wally Heard, one of the developers who built homes, recalled that the state had owned the property and made the land available for the project because there was a great deal of demand for low-cost housing. The state also provided financial assistance for buyers who qualified based on income.

“Those houses went real quick,” Heard said. At the time, city officials were focused on building homes to ease the housing shortage, and he didn’t recall anyone talking about the proximity to the river being an issue.

“I had no clue on my side at all about it being problematical,” Heard said. “I just don’t think it was taken into consideration at all, to tell you the truth.”

Calderón and her farmworker husband, Ciro, were among the first families who bought homes. They were pleased they could afford the property.

Calderón and her neighbors were told the smelly river would be encased in a pipe and covered up with dirt. A park would be built on top of it.

“We didn’t know how harmful the river was,” Calderón said, sitting at her kitchen table. “If from the start they had told all of us who live in this area how much it could harm us to live along such a polluted river, we wouldn’t have bought anything — nobody here, no one, due to the pollution.”

A neighborhood park eventually was built next to the river with a playground and a baseball field. But the sewage kept flowing, and the work of putting the river in a pipe was never carried out.

Calderón and her family learned to cope with the odors.

“When I have my grandchildren here and it seems the smell is coming, I tell them, ‘Go inside, kids, go inside.’ Because the smell is very strong,” Calderón said. “They stop playing and I put them inside and spray Lysol or whatever so that you don’t notice the bad smell.”

Water from the river isn’t used for drinking or irrigation. People treat the river like an open wound on the landscape, an off-limits zone to avoid.

It flows beside the neighborhood down in the ravine, where thickets of scrubby brush grow alongside the water.

The river was encased underground in Mexicali two decades ago, and for years people in Calexico have been pressing for a similar project on the U.S. side.

In 2009, Calderón visited Sacramento to demand action together with members of a local nonprofit group called the Calexico New River Committee. They urged lawmakers to support a bill that called for cleaning up the river and building a park along it. Though that bill was approved, Calderón has been frustrated by the lack of action since then on the so-called New River Improvement Project.

“We want them to cover up the river,” Calderón said. “We want them to put it in a pipe so that all the pollution it carries isn’t exposed to the air. That’s all we’re asking for. But they say the project of putting in a pipe costs a lot of money. Mexico has already done it, but not here in the United States.”

California officials are now working on a plan to put the river in a pipe and reroute it away from the neighborhood to wetlands farther downstream. A statewide bond measure that was approved by voters in June will provide $10 million to pay for part of the river project.

Timeline: A river that has been toxic for decades

Calderón says it’s about time something is done, but she’s still skeptical after years of disappointments. She and her husband are sometimes asked why they don’t just move away. She said they’d definitely consider moving if they could afford it, but they can’t. And this is their home.

Nowadays, the home values on Calexico Street remain low compared with other parts of the town, with most estimated between $150,000 and $180,000.

Some residents say the river’s odors have gotten a bit less noxious in the past several years. But it’s still bad enough that when the smells of sewage fill the air, people shut their doors and windows and stay inside.

When it’s hot outside, fumes resembling the stench of rotten eggs often fill the neighborhood — the telltale sulfur smell of hydrogen sulfide gas.

“It’s a stench that even hurts to breathe,” Calderón said. “Breathing it makes your nose burn.”

She and her neighbors have found that their air conditioners often need to be repaired or replaced because metal parts quickly corrode and refrigerant leaks out. That makes Calderón wonder: If the metal air conditioners are corroding because of something in the air, what other effects might the pollution have on their health?

Hydrogen sulfide can be released into the air from decaying material like dead fish or decomposing algae in lakes and rivers, or from sewage or industrial processes. One source of the toxic gas is the Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station, which spews out steam and particles south of Mexicali.

The gas is also released by sewage-treatment plants. Calexico’s wastewater plant sprays water into the air in an aeration pond across the river from Calderón’s house.

Air conditioners tend to have corrosion problems near wastewater plants because the gases dissolve metallic joints inside the units, said Cesar Rodriguez, the manager at Arctic Air Conditioning in El Centro. Rodriguez said he suspects the problems with corroding air conditioners next to the New River are mostly due to fumes from the sewage plant. How much the river might be contributing to the problems isn’t clear.

Responding to complaints about the stench, the California Department of Public Health carried out a study in 2008 and 2009. The department said in a 2010 report that Calexico’s higher-than-normal hydrogen sulfide levels “are likely the result of the emissions from multiple sources, both locally and in Mexicali.”

The researchers tested the air along the riverbanks and elsewhere, and said the river didn’t appear to be the source of the hydrogen sulfide odors in the neighborhood because the gas levels were higher in other parts of Calexico.

Near the border, the river’s fumes add to a potent mix of air pollution that includes dust, smoke spewing from factories, exhaust from cars and trucks, and dark columns billowing from burning trash in Mexicali.

This area of the border has some of the dirtiest air in the United States and Mexico. Imperial County has the highest rate of asthma-related emergency-room visits for children in all of California.

Statewide data also shows the county has relatively high rates of some types of cancer, including cancers of the brain and nervous system, digestive system and myeloma.

Calderón said while much remains unknown and unstudied about the health effects of living by the river, one thing is clear: Something should have been done long ago to protect people from the pollution.

In her front yard, plastic swings dangle from a tree. Her grandchildren play here when they visit.

“In the future, I don’t want it to affect my grandchildren, the whole new generation,” Calderón said. “We want our home, our community, to be a community without so much pollution danger.”

SUPPORT JOURNALISM: Subscribe to one of more than 100 local publications

‘You can’t go outside'

To investigate illnesses in the neighborhood, Desert Sun journalists went door-to-door interviewing residents on a single block of Calexico Street. Of 15 people who answered the door, three said they or their relatives have thyroid illnesses. Several people said they have asthma or battle severe allergies.

They included retirees, elderly former farmworkers, a banquet organizer, an electrician and others. Many said the stench bothers them and they avoid going outside when the odors are strong.

Candelaria Nieblas said she keeps a nebulizer handy to treat her asthmatic 16-year-old son, Jesús Iván, when he has coughing fits. The boy was born with the genetic condition DiGeorge Syndrome and requires constant care.

Lately, his asthma has been under control. But Nieblas recently learned that she’s developed asthma, too.

“I have a cough that won’t go away,” Nieblas said, sitting on her front porch. Sometimes, she coughs so much that her back aches from all of the heaving.

Nieblas has started getting weekly allergy shots and uses an inhaler in the morning and at night. She notices the smell of sewage hanging in the air and suspects it’s taking a toll.

Down the block, Berta Prado also suffers from asthma and uses an inhaler.

“There are times when the odor is very strong. You can’t go outside,” said Prado, a former farmworker whose backyard faces the river. “The odor is so bad it burns my nose.”

Prado has an adult daughter with a thyroid illness, which has led to trembling and once caused her hair to fall out.

Medical studies have found that while much of the risk of developing autoimmune thyroid disease is due to genetics, various types of pollutants — such as lead or PCBs — may affect the thyroid and play a role in developing thyroid illnesses.

Prado said years ago residents circulated a petition calling for the river to be put into an underground pipe.

“I feel disillusioned because they don’t do anything,” Prado said. “Many people have sold, and they leave.”

Nearby on Grant Street, Antonio and Maria Elena Ramírez have been living in a home next to the river for 28 years. They said they suffer severe headaches, allergies, watery eyes and infections, and they blame the river, which is several hundred feet from their backyard.

Antonio Ramírez takes an antihistamine to control his allergies. When the odors are strong, he and his relatives put on Vicks VapoRub to mask the smells. At night, they close their doors and windows to keep out the smell.

“I can’t stand the odor that comes from the water,” Ramírez said. “It hurts your eyes. It gives you a headache.”

Other illnesses have also appeared among his neighbors. A decade ago, a neighbor’s preteen daughter had a serious illness that gave her tremors and made her lose her balance, Ramírez said, and her family decided to move away to escape the pollution. He’s not sure what she had.

Ramírez said he’s convinced the illnesses are a direct result of living next to such a filthy cesspool.

“But there’s no doctor, no hospital who can give us a record saying, ‘You’re sick because of the river,"' he said.

Ramírez, a former farmworker, has walked with a cane since he suffered an accident years ago. Sitting in his living room, he said no one hangs clothes outdoors to dry because the fabric will absorb the stench.

Sometimes, windstorms sweep across the desert, sending clouds of dust swirling from the riverbanks through the neighborhood.

Ramírez has joined his neighbors in complaining to politicians, including state Assembly members, senators and city council members. He feels frustrated by years of broken promises, and he sees it as a shameful injustice that the problem still hasn’t been fixed.

“They all say, ‘We’re going to investigate.’ But they’ve failed as politicians,” Ramírez said. “They don’t do anything.”

Ramírez remembers a very different New River when he was a boy growing up in Mexicali in the early 1950s.

“It was clean, crystal clear water,” he said. “It was beautiful swimming there.”

He remembers jumping off a wooden bridge into the water, which was mainly runoff from farms around Mexicali.

“We fished. There were turtles,” Ramírez said. “Everyone who lived here in Calexico and Mexicali went swimming and absolutely nothing happened to us. It was a clean river.”

As Mexicali grew and more factories were built, sewage and industrial effluent poured in, and people stopped swimming in it.

“Now it’s sewage. It’s not a river,” Ramírez said. “They should take away the name New River.”

“The name should be changed to New Sewage,” he said.

One afternoon, when the river was giving off relatively mild odors, Ramírez walked into his backyard and looked toward the river. He said he hopes government agencies pick up the pace and finally rid the neighborhood of pollution.

“I don’t know when they’ll do it,” Ramírez said. “I hope before I die.”

A river partially hidden underground

The New River begins south of Mexicali, where the lush farmland irrigated with Colorado River water contrasts with the open desert beyond.

The river channel was carved by floodwaters in 1905, when Colorado River water burst through a control gate in a blunder during construction work. As the water poured north, it created the Salton Sea atop an ancient lake bed and scoured the channels of the Alamo and New rivers. Both rivers have kept flowing ever since.

Runoff from fields of alfalfa and wheat courses through ditches and feeds the New River. On the outskirts of Mexicali, putrid water flows in from ditches filled with heaps of garbage and discarded tires.

In parts of the city, open ditches filled with raw sewage run between factories, garbage dumps, cattle corrals and shacks. The filthy runoff collects in ditches, and many of these reeking arteries reach the New River.

The water collects in a series of lagoons, then passes through a system of underground tunnels as it runs through Mexicali, serving as a drain for the city.

Even with the river hidden underground, everyone knows it's there. When people give driving directions, they often say in Spanish, "You go down Rio Nuevo ..."

Down in the ravine by the river, homeless people have built small encampments among the bushes.

The river passes Nosotros Park, where children play soccer, basketball and softball in the afternoons. Then it meanders through Imperial Valley farmlands, gathering farm runoff along the way, until it meets the Salton Sea, sending a brown plume into the lake.

For decades, the river has been synonymous with pollution. The author William T. Vollmann explored it while researching his 2009 book “Imperial.” He enlisted a companion and cruised the river in an inflatable raft using wooden oars.

He described the New River as “a horror” and a “reeking brown cloaca,” saying it gave off a “stench of excrement and something bitter like pesticides.”

On summer nights, he wrote, the sickeningly rich stink “remains on one’s clothes and even on one’s tongue.”

‘It’s affecting these agents’

Despite its stench, the river offers a path for people who are desperate to cross the border.

Border Patrol agents say smugglers charge migrants $5,000 to $7,000 to lead them across, and groups are regularly spotted trying to slip past in the river.

One night in September, floodlights reflected off the dark water as several agents kept watch from their trucks on the banks.

When they spotted two young men wading through the water, agents appeared on the edges of the steep banks and shined their flashlights on them. The two stopped under a bridge, their soaked clothes clinging to them, and slowly waded back upstream. Once across the border, they entered a culvert and disappeared into the darkness.

An agent said over the radio that the two were “TBS” — they had turned back south.

“This is their game, night after night,” Agent Joel Merino said. “I’m sure they’re just waiting.”

Often the border crossers come out of the concrete culvert. Its mouth is covered with crisscrossing bars, but sections of the bars have been removed to allow for easy access.

They submerge themselves up to their noses. They try to hide under floating debris or in the vegetation along the water’s edge.

Metal gates block the river just north of the border, and some people are captured when they climb out to skirt the gates.

Border Patrol agents say people who are spotted in the river sometimes throw rocks or sticks, or sling mud at them to try to escape. The agents are instructed to keep out of the water unless an emergency situation arises.

“It’s so polluted,” Merino said, looking down at the water. “To me, it looks like old antifreeze.”

The riverbanks are littered with plastic bottles and scraps of soggy clothing. Old tires sit lodged in the mud.

As the agents stood watch, wind picked up clouds of dust along the riverbank and sent it swirling into the night. The powdery dust coated their boots and pants.

Merino has developed allergies working along the border. He’s found that when he’s assigned to the river, his skin itches and his eyes get irritated and water up.

Other agents say working next to the river gives them headaches. When the water reeks, they try to limit their exposure by stepping into their Chevrolets and keeping their windows shut.

“There’s times during the summer,” Merino said, “where the odor of the river is so pungent that it will make you nauseous.”

He paused when he heard a voice on his radio: “A pair is coming back.”

Another agent stood at the riverbank, pointing his light down into the reeds and brush.

In the gleaming floodlights, two men emerged from the vegetation. They were neck-deep in the river. As they swam upstream, their heads went underwater.

Watching them retreat, Agent Ruben Sigala said: “They don’t understand the dangers of putting their face in it.”

Another agent, Jose Enriquez, said he worries about the health effects of working along the river.

“Studies need to be done. We really don’t know what kind of risk we’re putting ourselves in," Enriquez said. “It is dangerous. I, for one, don’t want to ever touch that water.”

The union that represents Border Patrol employees has been voicing concerns that the river is making people sick.

“We have case after case after case of people getting headaches, rashes, flu-like symptoms,” said Mike Matzke, president of Local 2554 of the National Border Patrol Council. “One agent we had, it really affected him to the point where it blurred his vision.”

Matzke represents agents in the El Centro Sector, roughly a third of whom are stationed in Calexico and regularly work along the river.

“I’d say every agent at Calexico station has been exposed to the New River one way or the other,” Matzke said. “It’s inevitable.”

That includes getting splashed, slipping and falling into the water or going in on purpose to capture migrants. When agents get soaked with river water and mud, the nearest showers are in the locker room at their station.

“Some agents, even after they’ve showered, are just itching all night long,” Matzke said. “They scratch and now you’ve got an open sore. It lasts a couple days. They’ll break out.”

When someone goes underwater completely and swallows water, the symptoms appear quickly.

“Usually when a migrant gets a mouthful of that water, they’ll just start throwing up pretty much uncontrollably, and all we can do for them is sort of hose them down and keep washing the throw-up down the drain until they stop,” Matzke said.

It can feel like coming down with severe food poisoning, he said. Matzke knows from experience: Once, as he was pulling a man from the river, a splash of water landed in his mouth and he started vomiting.

Matzke has been talking with managers about what can be done to help agents, such as providing outdoor decontamination showers and more protective gear, as well as blood tests to monitor their exposure to pollution.

Many agents feel they should get extra “hazard duty” pay for working along the New River.

Border Patrol agents have raised similar complaints in San Diego, where raw sewage from Mexico regularly flows in the Tijuana River and fouls beaches near the border.

Concerns about the hazards of working along the Tijuana and New rivers were at the center of a 1994 lawsuit by the union against the federal government. That case ended with a $15 million settlement in 2004. The terms included several pledges by the government, including that agents would not be disciplined for refusing to enter the rivers, “except in cases where life is endangered.”

In the past year, the Tijuana River has again become a high-profile problem. San Diego-area beach cities sued the federal government in March over the sewage spills, which have led to repeated beach closures and have been blamed for declines in property values. Then, in September, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra and the state’s San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board filed a lawsuit accusing the federal government of violating the Clean Water Act by allowing untreated sewage to pollute the river.

Becerra said the lawsuit aims to protect public health and natural resources, and “get those responsible to clean up this mess.”

In the complaint, lawyers for California said the violations of the Clean Water Act relate to the continuing discharge of “millions of gallons of waste consisting of untreated sewage, bacteria, pesticides, chemicals, and heavy metals” from sewage treatment facilities owned and operated by the U.S. Section of the International Boundary and Water Commission. They accused the federal agency of failing to properly manage and operate the wastewater facilities, and said the violations show an “unwillingness to address pollution that crosses into the United States from Mexico, absent being compelled through legal action.”

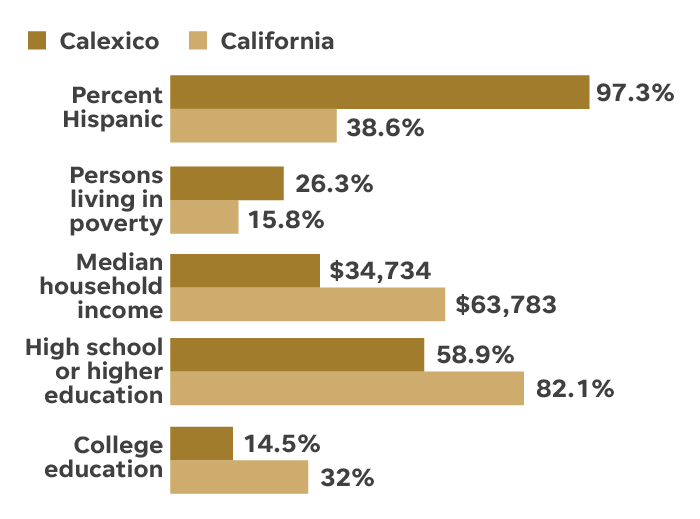

The pollution of the New River, which runs through a poorer community that is 97 percent Latino, hasn’t drawn such a strong response in recent years. No similar lawsuit has been filed by state authorities over the New River.

As for the Border Patrol agents who work at the river, Matzke said their biggest worries are the unknowns, including what’s dumped into the water in Mexico and the viruses that fester in the sewage, from typhoid to cholera.

Occasionally the agents see people fishing in the river, and they will tell them it’s not a good idea because the water is polluted. But sometimes, the anglers ignore the advice. And even though some of the pollutants in the New River accumulate in fish tissues, the state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment has advised people that women under age 45 and children “can safely eat” one serving per week of carp, or four servings per week of tilapia caught in the river.

Matzke said he would never eat fish from the river. Some days, the agents see fish swimming, and other days they see dead fish on the surface.

“Who knows what’s in it on a day-to-day basis,” Matzke said. “The valley’s got a lot of pollution problems, between pesticides, the New River and air quality. I’m 100 percent sure it’s affecting these agents.”

The U.S. government recently built a new port of entry next to the river and a new 30-foot-high steel fence along the border in Calexico. Workers tore down an old metal fence that had run up to the edges of the New River, and replaced it with the new barrier.

Matzke said the taller fence should dissuade people from trying to jump down from the top of the barrier. But that doesn’t mean it will stop the flow of people. In fact, he said, the bigger fence might funnel more people toward the river.

Matzke has been working in the area for 11 years. And one question has stayed with him ever since he arrived from Wisconsin: Why has this badly polluted river been neglected for so long?

“If this river were in Wisconsin, people would lose their minds,” he said. “Politicians would lose their jobs. They would be like, ‘Clean this up.’”

Tracking toxic pollution

The New River is filled with bacteria at levels far above the threshold considered safe for human contact.

The concentrations of fecal coliform bacteria are measured with an estimation called “most probable number,” or MPN, per 100 milliliters of water. California’s regulatory goal for people to safely swim in freshwater is 400 per 100 milliliters. Monthly samples from the New River last year ranged from 12,000 to more than 160,000 — reaching more than 400 times the swimmable limit.

Water tests show the river is one of the most polluted in California.

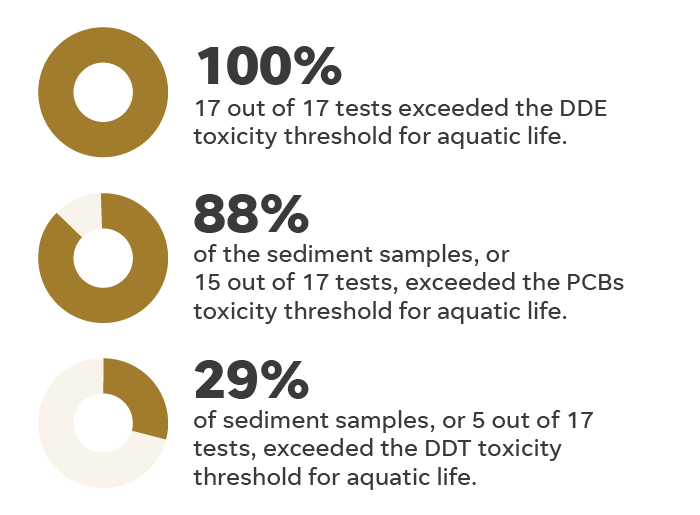

One of the pollution measures used by the State Water Resources Control Board is toxicity. In the laboratory, researchers test samples of sediment taken from a river by observing the effects on aquatic animals — in this case a tiny crustacean called Hyalella azteca — and watching how many of the creatures die.

Statewide data from 2002 to 2015 revealed that about 46 percent of the sediment samples from the New River exceeded the toxicity threshold for the creatures. Of the rivers tested in California, the New River had one of the highest percentages of samples found to be toxic.

Scientists from the University of California, Riverside, have also used monitoring data collected by state officials to analyze pollution in the New and Alamo rivers and the Salton Sea. The researchers studied the contaminants recorded in water, sediment and fish in the two rivers and the lake between 2002 and 2012. They found the pollution in the New River stood out.

In their 2016 study, the scientists said the levels of toxic metals — including cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury and nickel — exceeded thresholds for aquatic life in the river sediment at the border. The testing also showed elevated levels of pesticides including chlorpyrifos, dieldrin, pyrethroid insecticides and DDT, and other carcinogens including PCBs and PAHs.

PCBs have been found to cause cancer in animals. Though the chemicals were banned in the U.S. in 1979, they can still be found in insulation, electrical equipment, transformers and other systems that were manufactured before the ban.

PAHs are created by burning fuel or other materials, and studies have shown links to cancer.

The scientists focused their study on the potential effects for fish and wildlife, not on human health. They said that “persistent toxics are prevalent” in the rivers and the Salton Sea, and that the levels are especially high in the New River at the border.

“The risk for ecological damage is clear for those contaminants that exceed those thresholds,” said Daniel Schlenk, a professor in UC Riverside’s Department of Environmental Sciences. He said it’s not clear whether the contaminated sediment in the river is going all the way downstream and making it into the Salton Sea, and if it is, how much.

But the effluent that flows out of Mexicali carries a load of phosphates and other polluting nutrients, which contribute to algae blooms in the Salton Sea. And the chemicals in the river may be contributing to the sea’s deteriorating ecosystem.

The Salton Sea is shrinking as strains grow on the dwindling Colorado River and as a water-transfer deal shrinks the amounts of water flowing through farm ditches into the lake. The retreating shorelines have already left about 20,000 acres of lake bed dry and exposed to the desert winds.

In the coming years, the lake is projected to shrink dramatically, sending more dust billowing through communities that already suffer from high asthma rates.

If accumulated heavy metals, chemicals and pesticides are ending up in the dust — both along the New River and on the shores of the Salton Sea — the river’s toxic pollution may be affecting people’s lungs miles away from the border.

Questionable oversight

Ponds filled with sewage spread out in the desert south of Mexicali, forming an island of green in a sandy landscape dotted with creosote bushes.

Las Arenitas Wastewater Treatment Plant was built to handle the growing volume of sewage from Mexicali. Effluent from the plant flows into a wetland, creating a 250-acre oasis where birds soar above the reeds. The water drains into the Hardy River, which flows south toward the Sea of Cortez.

When the plant opened in 2007, it began taking in a large portion of the sewage that previously had gone into the New River. That reduced the river’s flow across the border. It also brought about a marked improvement in the river’s water quality, including a decline in bacteria levels.

Officials on both sides of the border say that during the past decade, Mexican authorities have improved their system of regulating factories’ wastewater discharges.

But significant weaknesses appear to remain in the system of oversight and enforcement.

Federal regulators in Mexico require factories to treat any wastewater that’s released into ditches. The state-run water utility, the Mexicali Public Services Commission, is in charge of regulating companies that discharge wastewater into the sewer system, and requires them to treat effluent to meet standards before letting it run into the sewer.

“Every industrial plant is registered with us and is required to comply with federal rules,” said Luis Antonio Hernández, chief of the utility’s wastewater department.

If a business doesn’t comply with the regulations, he said, officials typically reach an agreement with a company and give managers a deadline to come into compliance.

Hernández said some companies have occasionally been fined, though he didn’t give details.

A tally released by the utility showed that out of 114 registered industrial businesses, regulators detected six cases during 2016 and 2017 in which companies violated wastewater regulations based on indicators including levels of dissolved oxygen or total suspended solids.

The companies cited for violations included Isoclima de Mexico, which makes security glass for armored vehicles; Tecnologías Internacionales de Manufactura, a metal- and pipe-making company; Chromalloy, a company that produces engines and components such as turbine blades; Rocktenn de Mexico, which makes cardboard boxes; Fruvemex Mexicali, which sells fruit and vegetable products; and J. Cox, which specializes in injection plastic molding, making products such as brackets for televisions.

In all six cases, the companies agreed to come into compliance and took care of the problems, said Carlos Félix Verdugo, the utility’s environmental-control coordinator. He said in an email that violations are typically spotted after complaints or during inspections by officials.

The Mexicali Public Services Commission took over its regulatory role from the Baja California state Environmental Protection Department in 2016. California water regulators had been pushing for that change.

“Prior to 2016, there was basically minimal oversight to none,” said Jose Angel, who recently retired as executive officer of California’s Regional Water Quality Control Board. He said it was awkward having one state agency running the sewer system and another in charge of enforcement, and it made sense to finally bring both functions under a single agency.

Since that handover, companies have been required to turn in water-quality reports annually to renew their sewage-discharge permits. Officials say state regulators check information on companies’ permit applications, and water samples are regularly collected and analyzed to check that factories are properly treating their wastewater.

“The state does quite an effective job of providing oversight,” Angel said. He said that unlike years ago, now not a single foreign-owned maquiladora is known to be discharging directly into the river. He also credits Mexican authorities with eliminating untreated wastewater discharges from slaughterhouses into the New River.

Angel said although industrial wastewater still contributes to the pollution in the river, and although the heavy metals in industrial effluent pose threats for the ecosystem, he thinks the bigger problems nowadays are the high levels of bacteria and the increasing spills of raw sewage into the river.

Questions remain about how thoroughly Mexican officials are regulating wastewater discharges from the city’s maquiladoras. Records released by the utility show some companies had yet to obtain new permits during reviews last year. And it’s not clear how often the agency detects the dumping of toxic chemicals into the sewer system.

Much of the sewage that ends up in the New River flows through the Zaragoza wastewater-treatment plant, which officials say improves the water quality but doesn’t disinfect the water and doesn’t remove chemicals or heavy metals.

Some of the city’s large factories and power plants are regulated by Mexico’s federal government and are required to report on discharges of wastewater containing a list of toxic substances. A government database shows that since 2004, companies in Mexicali have discharged water with a list of pollutants including arsenic, cadmium, cyanide, chromium and mercury.

The companies that have reported releasing those substances include Cromsa, which specializes in chrome-plating, and paper-products maker Fábrica de Papel San Francisco, as well as other factories, power plants and a hospital.

The information is self-reported, and the companies appear to be reporting wastewater releases that are permitted under Mexican regulations. The database doesn’t list the legal limits for discharges. The records also don’t specify where the wastewater has been released or say how much has ended up in the New River.

Polluted and repolluted

What’s clear is that the records describe only a fraction of the pollution that’s going down drains and flowing into the river.

In assessing the pollution levels in the river and the oversight of factories’ discharges, The Desert Sun shared data with Robert Bowcock, an independent water-quality consultant. Bowcock said water-testing results since the early 2000s show that there has been a decrease in the levels of contaminants from industrial wastewater, but that severe pollution remains in the river.

Because heavy metals and chemicals have accumulated over the years in the riverbed and the soil along the banks, the river is filled with “recalcitrant contamination” that continues to emerge in the water and ends up in the Salton Sea, Bowcock said. Unless those accumulated toxic deposits are cleaned up, he said, “the river’s going to constantly be repolluted from the sediments.”

Of particular concern are the accumulated PCBs in the sediment along the river, he said, and the possibility that these and other toxic chemicals may end up in airborne dust.

Bowcock said many of the heavy metals and minerals that appear in the wastewater are already in the Colorado River water that flows into Mexicali, and the contaminants emerge from the factories’ industrial processes at much higher concentrations.

While some factories appear to be treating their effluent, many wastewater discharges remain unregulated and are highly suspect, Bowcock said.

“I know that stuff is still being dumped,” Bowcock said. “For every bigger legitimate factory that’s being showcased, there’s probably 10 cheaters around the corner.”

The Mexican federal government tracks discharges for only a fraction of the industrial plants, and because the regulatory system relies on self-reporting by companies, he said, discharges of industrial waste may go undetected or unreported.

“Some of these factories are discharging and you’d never see it,” Bowcock said. “From a regulatory standpoint, there are still many more cheaters that need to be brought to the table.”

For many years, the New River was described as the most polluted river in North America. And while experts no longer describe it that way, Bowcock said the improvements to date are far from being a success story.

“It’s still probably one of the most polluted rivers in North America. The question comes down to, at what rate do we want to clean it up? And at what rate do we want to clean up those chemicals that were already released into the environment?” Bowcock said. “The coordinated, concentrated effort of cleaning it up has not taken place. And it comes down to money.”

Decades of neglect

On both sides of the border, American and Mexican officials have acknowledged for decades that sewage and industrial waste are seriously polluting the New River. But efforts to address those problems have repeatedly fallen short.

In the 1970s, as maquiladoras were proliferating in Mexicali, the stench of untreated sewage drew increasing complaints. President Jimmy Carter and Mexican President José López Portillo touched on the issue in a joint statement in 1979, calling for “further progress toward a permanent solution to the sanitation of waters along the border.”

In 1980, Mexico and the U.S. adopted an agreement establishing water-quality standards for the New River and calling for eliminating discharges of raw sewage. But the sewage and industrial waste kept flowing, and the requirements under that agreement, which was known as Minute 264, have never been enforced. California officials say Mexico has been in chronic violation of those requirements ever since.

The two governments signed an agreement in 1987 to jointly spend $1.2 million on sewer upgrades, and another agreement in 1992 to fund more sewer repairs and improvements.

But the problem of industrial waste from Mexicali’s maquiladoras remained unresolved.

In 1993, when the ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement gave an added boost to the maquiladoras, Imperial County pressed the U.S. government to do more about the New River.

The county’s Board of Supervisors petitioned the Environmental Protection Agency, urging the government to issue a rule that would require testing of chemicals in the New River and calling for it to conduct a comprehensive health assessment. The EPA denied Imperial County’s petition but acknowledged the New River was extremely polluted and said the agency would fund testing by state regulators.

Then the EPA took an unusual step to try to pierce the secrecy and find out more about the chemicals that factories were releasing into the river. In 1994, the agency sent 117 letters to the U.S. parent companies of maquiladoras in Mexicali, asking them about the chemicals they were using and releasing into the environment.

Only eight companies responded. The EPA then turned to its authority under the Toxic Substance Control Act and issued subpoenas to 95 U.S. parent companies of maquiladoras that hadn’t responded. That yielded 75 responses from companies, some of which said they no longer owned or operated a plant in Mexicali. In the end, the EPA received responses from 64 parent companies of maquiladoras in Mexicali.

Some of them reported using chemicals at levels exceeding thresholds under U.S. law. Those pollutants included sulfuric acid, lead, silicon dioxide and aluminum oxide, among others. A few companies reported releasing chemicals into the sewer system including hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, isopropyl alcohol, sodium hydroxide and boric acid.

The EPA said in a 1995 report that the “information contained in the responses was insufficient to permit the agency to independently assess whether the data contained in the responses from the U.S. parent companies are representative of the actual releases of industrial pollutants from the maquiladoras.”

The agency concluded that continuing to monitor the New River through testing would be the “most effective way to provide accurate information on the pollutants in the river.”

That was the one and only time the EPA used its subpoena authority to seek information from maquiladoras. Some of the companies had argued that the agency overstepped its authority and that its jurisdiction didn’t include factories outside the United States.

U.S. officials said they have since turned to other strategies. Nahal Mogharabi, an EPA spokesperson in Los Angeles, said the agency has taken “a more collaborative approach to address trans-boundary water quality concerns.”

“EPA has instead focused on constructing wastewater infrastructure in Mexico to prevent raw sewage from entering the United States,” Mogharabi said in an email.

After NAFTA took effect, Congress in 1996 began appropriating funds to build water and wastewater infrastructure on both sides of the border. The EPA has since contributed more than $707 million for water and sewer infrastructure projects along the border.

The federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry also carried out a study analyzing the health impacts of pollution in the New River. The agency said in its 1996 report that the river “poses a potential public health hazard because area residents could be exposed to fecal streptococci, and other pathogens through contact with contaminated surface water and foam.” It said previous studies found the river was loaded with high levels of bacteria as well as viruses that were “reported to be capable of producing polio, typhoid, cholera and tuberculosis.”

The agency said water tests showed metals including lead, cadmium, thallium and antimony in the water, as well as a list of toxic chemicals and pesticides. It recommended promoting “coordination and cooperation” between the U.S. and Mexican governments, curbing pollution, restricting access to the river, and advising residents not to eat fish and to avoid contact with foam in the water.

In the two decades since, California water regulators have repeatedly called for bigger pollution-fighting efforts.

In 2003, Executive Officer Phil Gruenberg of the Regional Water Quality Control Board wrote to the U.S. government to complain. He said the New River was in a “deplorable condition” and that Mexico was continuing to violate the 1980 water-quality agreement. If penalties could be imposed, he said, the pollution would have been corrected years ago.

“Countless promises have been made and broken, and the River remains just as polluted and dangerous as it was in 1980,” Gruenberg wrote in a letter to Wayne Nastri, who was then EPA’s regional administrator. The main victim, he said, is the predominantly Hispanic community in Calexico, and “Calexico’s suffering is environmental injustice.”

As the EPA increased funding to help pay for sewer upgrades in Mexicali, the money was routed through the North American Development Bank, an institution that the U.S. and Mexico created when NAFTA was adopted with a focus on improving environmental conditions in border communities.

Since 1997, the bank has administered dozens of U.S.-funded grants through the U.S.-Mexico Border Water Infrastructure Program, building and upgrading water and wastewater systems on both sides of the border in places from Brownsville, Texas, to Tijuana.

In Mexicali, the U.S. government’s contributions of more than $31 million to sewer projects have added to about $60 million in matching funds spent by the Mexican government.

The grants have paid for building pump stations and miles of new sewer lines. The funding has come with the condition that Mexicali’s utility require industrial plants to treat their effluent to limit the discharge of toxic pollutants.

After Las Arenitas wastewater plant began operating in 2007, California regulators saw an immediate decrease in bacteria levels in the river. In the past several years, though, Mexicali’s dilapidated and overburdened sewer system has again been plagued with an increasing number of spills. Millions of gallons of raw sewage have poured into the river, causing sudden spikes in bacteria levels.

Government records show how serious the problem has become. In response to a Desert Sun request under the Freedom of Information Act, the International Boundary and Water Commission released a list of sewage spills reported by Mexican authorities.

The list showed sporadic sewage spills in 2010, a single event in 2011, and then nothing until 2015, when three spills occurred. In 2016, the problems got much worse, with a total of 11 spills that sent millions of gallons of untreated waste into the New River. Five spills were reported in 2017, including one that dumped an estimated 122 million gallons of untreated sewage into the river.

The spate of overflows represents significant backsliding after years of progress, and the problems have angered people who live next to the river.

Luis Olmedo, who leads the environmental health nonprofit Comité Cívico del Valle, said officials on both sides of the border need to act.

“Mexicali kind of just sits on these issues and waits for the U.S. to bail them out,” Olmedo said. “They’re just putting Band-Aids on their water-treatment plants.”

In 2016, the North American Development Bank released a 419-page study diagnosing Mexicali’s sewage problems. The report said the sewer system suffers from “lack of maintenance” and infrastructure that’s beyond its “useful life” — and now needs about $80 million in upgrades.

New hopes, elusive solutions

Because the New River crosses the border, it falls under the jurisdiction of the International Boundary and Water Commission, which was created by the U.S. and Mexico in 1889 and is charged with overseeing agreements and settling disputes.

Alfredo De la Cerda has worked for the Mexican branch of the IBWC for more than two decades and heads its sanitation department. During a visit to the border fence, De la Cerda stood above the mouth of a concrete tunnel where the river emerges in a frothy pool.

“I remember coming here when I was a boy and saying, ‘Let’s go to the ravine.’ It was no-man’s-land,” De la Cerda said. “You’d find trash and you’d find cars and furniture. That was in the early '80s. Since then, there’s been great improvement.”

“When I was a boy and I came, I saw water that was totally black. Today, it’s a different color, green, which shows biological activity,” De la Cerda said. “I think between the '80s and the present, there has been great improvement.”

Still, he acknowledged work remains to be done.

“Any water that’s polluted with wastewater can definitely be a major health risk,” De la Cerda said, “but we’re continually working on solving all of those deficiencies.”

Yet, the river remains so polluted that when California water regulators visit to take samples, they slip on white protective suits, latex gloves and plastic face shields to avoid splashing any water on themselves. They step onto a narrow footbridge and use a pole to lower bottles into the water to take samples.

Officials at the state Water Quality Control Board credit Mexican authorities with achieving improvements in water quality during the past decade. They say they now have a good working relationship with their Mexican counterparts and regularly hold meetings where they share ideas about cleaning up the river.

But California officials say they are also concerned that Mexico’s prior commitments haven’t been enforced and that the spate of sewage spills points to a deteriorating situation.

“It’s one of the most impaired surface waters in the state,” Angel said. “If you look at the overall water quality, it’s unacceptable. It doesn’t meet our water-quality standards, period. That should be good enough for action.”

California officials have been alerting the federal government and calling for help for the past several years. By 2014, Angel said, state water officials viewed Mexicali’s deteriorating sewer infrastructure as an emergency.

“Now, it has become more of a crisis that needs immediate attention,” Angel said. At the same time, both Mexico and the U.S. government have been putting less funding toward sewer projects on the border.

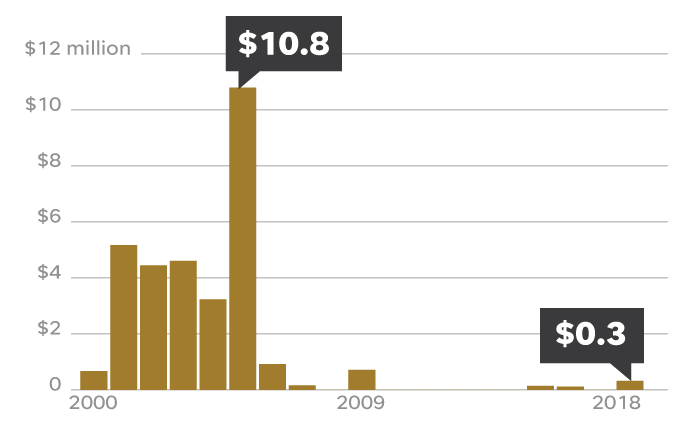

Records released by the North American Development Bank show that EPA funding for construction of water and wastewater projects on both sides of the border — through the Border Environment Infrastructure Fund — has dropped from an average of $58 million annually during the program’s first decade, from 1997 through 2006, to an average of $11 million a year from 2007 through 2016.

Last year, the EPA’s contributions totaled $8.8 million, and this year the funding decreased to $6.1 million. The downward trend looks likely to continue as President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans focus on downsizing spending on environmental programs.

The decrease in funding has meant needed sewer projects along the border have gone unfunded. Millions of gallons of sewage have continued to spill into the Pacific Ocean from the Tijuana River, fouling the beaches around San Diego. In Arizona, communities along the border have also been plagued by spills of raw sewage due to inadequate infrastructure in Mexico that hasn’t kept up with growth. Following a spill in September in Naco, Arizona, local officials declared a state of emergency. As a precautionary measure, they offered residents hepatitis and tetanus shots during vaccination sessions at a fire station and a school.

After the spate of sewage spills into the New River, Regional Water Board Chair Nancy Wright sent a letter in February 2017 to EPA officials asking for a meeting. She referred to the costly upgrades and equipment that Mexicali’s sewer system needs, and said the spills “pose a serious threat to public health to anyone that potentially comes in contact with the New River.”

Wright said she hoped to talk about how to address the problems “with a greater sense of urgency at all levels of government.”

She traveled to San Francisco for a meeting with EPA officials, and the agency later authorized spending $331,000 to pay for pumps and other equipment to prevent sewage spills.

As for the much bigger sewer overhaul that Mexicali needs, it’s not clear where the money might be found to pay for it.

One of the findings of the EPA-funded report on Mexicali’s sewage problems is that rates remain too low to cover the costs of properly operating and maintaining the city’s infrastructure. Michael Montgomery, assistant director of the EPA’s regional water division, said this means, “sadly, that we’re in a bit of a losing game.”

For some people in Calexico who have been waiting for fixes, the lack of progress toward a cleanup is maddening. California lawmakers have also voiced frustration at meetings during the past year, echoing many of the same complaints that water regulators have been raising for years.

“I’ve been working at this for a long time, and over the years I’ve been very disappointed with the IBWC,” said Sen. Ben Hueso, D-San Diego. “That agency is completely broken at trying to address these issues.”

Assembly member Eduardo Garcia, D-Coachella, said he’s frustrated by the lack of attention to the “core of the problem” in Mexico, and that more funding and cross-border cooperation will be key.

Angel said a vast amount of sewer infrastructure needs to be refurbished, expanded or rebuilt.

“It’s an $80 million problem,” Angel said. “We underestimated the cost of the problem that now we’re facing.”

Complicating matters, Mexicali now competes with other border cities for a smaller pot of funds.

“So, we’re in for quite a bumpy ride as the sewage infrastructure gets more dilapidated,” Angel said.

Angel spent more than 21 years working on the New River, and he said he finds it sad that fixes have taken so long.

Lasting solutions, he said, will require cross-border cooperation, help from the U.S. government, and, above all, more funding.

SOLUTIONS: 10 ideas for solving the pollution problems on the border

“If that threat is not addressed with a sense of urgency by our federal government, things are just going to get worse, and we stand to lose the hard-fought water-quality gains,” Angel said. “If we don’t assist and continue to cooperate with Mexico to address that problem, the New River water quality is going to go back to the 1990s.”

State officials sound much more optimistic about fixes on the north side of the border, and their upbeat outlook is echoed by officials at Calexico City Hall.

Back in 2009, then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed a bill that launched the New River Improvement Project and called for improving water quality, protecting human health and developing a river “parkway” in Calexico.

Those plans have been stalled for years, and now state officials are finally moving ahead using $1.4 million that was approved in 2016.

The project has been scaled back dramatically, though, since a first iteration was released in 2011. That initial proposal — which was prepared by a team of government officials, university professors and community leaders — suggested treating the entire river at the border by building a disinfection facility, along with a pump station and pipes, aeration devices to improve water quality, and screens to keep out trash.

The construction cost was estimated at $184 million, which turned out to be much more than proponents thought they could secure. Instead, state officials settled on a trimmed-down version of the project that’s estimated to cost $22 million to $24 million.

They have eliminated the disinfection plant and instead plan to encase the river in an underground pipe and reroute it away from the Calexico neighborhood. The pipe would start near the border and run more than a mile downstream, beyond the homes, where the river would emerge again.

Officials plan to build a “pump-back” system that would send treated effluent from Calexico’s wastewater plant into a new river channel, creating a relatively clean water feature that would run alongside a park with a trail for walking and bicycling.

The city has about $2 million set aside to begin building the “parkway” as the river is encased in the pipe. Calexico also has a new assistant city manager, Miguel Figueroa, who previously spent seven years campaigning to focus attention on the issue as executive director of the Calexico New River Committee.

He said he’s optimistic about the project.

“Now more than ever, we have things that are moving,” Figueroa said. “Finally, all the work was worthwhile.”

Both city and state officials say they hope to start construction soon.

Still, much of the funding for the state’s New River plan has yet to be approved. And another state plan to build ponds and wetlands on thousands of acres of dry lake bed around the Salton Sea has fallen behind schedule.

Officials have $10 million available so far for the New River project from the bond measure that California voters passed in June. Voters in November rejected another bond initiative, Proposition 3, which would have freed up another $10 million for the New River.

The funding shortfall isn’t the only reason why California officials decided not to build a plant to treat the entire river. In a memo, Angel wrote that doing away with the disinfection plant made sense because the river’s flow may dwindle by up to half in the next 10 to 15 years — and “to near zero in the long-term, as Mexico retains and treats more of the wastewater.”

The New River has already been shrinking for years. The flow decreased in the early 2000s when some wastewater began to be used for cooling two power plants, and again in 2007, when a large share of the city’s sewage started flowing to the new treatment plant south of the city.

If the New River Improvement Project doesn’t start to move along more quickly, the river could run dry and leave its toxic legacy blowing in the wind.

Reporter Pamela Ren Larson contributed to this article.

Help us investigate: Do you have a tip to share about pollution along the U.S.-Mexico border? Contact reporter Ian James at ian.james@desertsun.com, 602-444-8246 or on Twitter at @ByIanJames.

READ THE FULL SERIES: Poisoned Cities, Deadly Border