Care and Isolation Unit

The Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) recently completed construction of an integrated research facility with BSL-4 research space at its Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) in Hamilton, Montana. As part of the project, NIAID contracted with St. Patrick Hospital and Health Sciences Center (SPH), a regional referral medical center located in Missoula, Montana, for provision and staffing of a patient isolation facility to support the RML BSL-4 research program. The facility, known as a care and isolation unit (CIU)[23] was designed to care for RML workers who had either known or had potential exposure to, or illness from, work-related diseases. The facility had to be located within 75 miles of RML, had to provide the full range of standard in-patient care, including intensive care, and had to meet the facility design guidelines of the National Institutes of Health, Division of Occupational Health and Safety (NIH DOHS).[24] Furthermore, the hospital had to supply the personnel to provide the full range of medical and nursing care and to be able to accept a patient within 8 hours (this would entail notification of key members of the hospital hierarchy, transferring patients if the rooms were currently occupied, securing adequate nursing and support staff, and carrying out systems checks to ensure that air handling systems and autoclaves were operational). In addition to the physical facility, a training program for critical care nurses, physicians, and other medical personnel was a major component of the contract.

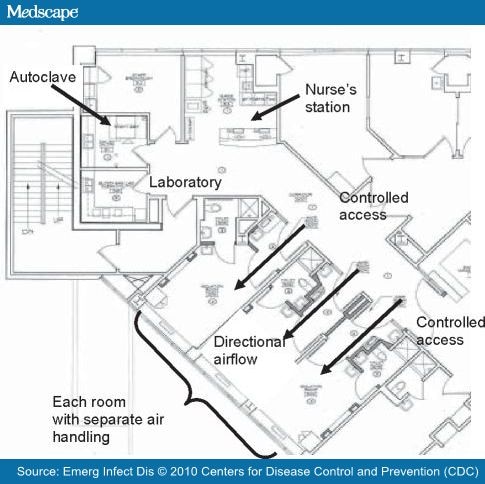

To satisfy the NIH requirements for the CIU, the following elements were needed: 1) access control, i.e., the ability to restrict entrance into the CIU to authorized persons only; 2) three separate stand-alone rooms, each with a bathroom and shower, separate air handling, and an anteroom separating the patient room from the hallway; 3) directional air flow from the hallway into the anteroom and from the anteroom into the patient room; 4) a dedicated exhaust system providing ≥12 air exchanges per hour to the patient rooms (including ≥2 outside air changes per hour); 5) passage of exhaust through a HEPA filter to the building exterior ≥8 feet above the rooftop and well removed from air intake ducts; 6) room surfaces constructed of seamless materials amenable to topical disinfection; 7) the capability for the full range of intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring and support, including the ability to perform limited surgery, hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, Swan-Ganz catheter placement, and hemodynamic monitoring; and 8) a separate autoclave within the CIU for sterilizing all items that come out of a patient room.

SPH was selected to provide these services and facilities. SPH is a not-for-profit medical center under the sponsorship of the Sisters of Providence. It has 195 acute care beds, and >10,000 patient admissions per year. The full range of standard specialty medical care is available within the hospital, including 24 hour, 7 day/week availability of specialists in critical care, infectious disease, and all surgical subspecialties.

SPH retrofitted 3 adjacent rooms within the existing medical ICU (MICU) to create the CIU. A set of doors was installed to control access to the CIU from the MICU, and these would remain open when the CIU was not in use (Figure). A separate fully equipped nursing station was constructed, with closed circuit television monitoring for each of the 3 rooms. After construction, the CIU was inspected and approved by officials from NIH DOHS. Under normal circumstances, the CIU operates either as 3 conventional MICU rooms or as isolation rooms for patients with community-acquired illnesses for which isolation of airborne pathogens is needed. If a patient from RML should require admission, any current occupants would be transferred, and access would be limited by closing off that section of the MICU.

Figure.

Floor plan of the Care and Isolation Unit, St. Patrick Hospital and Health Sciences Center, Missoula, MT, USA.

In addition to the physical aspects of the CIU, several other elements were developed. Specific policies and procedures were written that deal with all aspects from admission to discharge, including unique aspects such as clean up of infected bodily spills, donning and doffing of personal protective equipment (PPE), and use of the autoclave. Support of hospital administration, physicians, nurses, and support personnel was critical. This backing was enlisted primarily by mounting an educational campaign that stressed the true risk for nosocomial transmission of these agents, as well as the recognition that the increased resources that would be provided to the hospital could greatly enhance capacity for handling community-acquired infections.

One feature dealt with preparing the hospital staff to care for such exposed persons. To accomplish this feature, we developed a detailed curriculum, which can be presented during a 1-day training workshop. This workshop includes didactic information, patient care scenarios discussed in group settings, and hands-on training. Simulation of various patient care activities (hand hygiene, donning and doffing of PPE, cleanup of body fluids, and rendering ICU level care to a patient) is conducted by using programmable mannequins and either tonic water or Glo Germ (Glo Germ, Moab, UT, USA), both of which fluoresce under ultraviolet light, to simulate infectious body fluids. Continuing education credits are granted for participation. Competence is maintained with quarterly demonstration of proper technique, review of CIU-specific policies and procedures, and required utilization of a series of online problem-oriented patient care scenarios. Training videos have been developed that demonstrate proper technique for spill cleanup, donning and doffing of PPE, processing of patient specimens, and processing of biohazardous waste, including use of the autoclave. Finally, detailed educational modules have been developed for each of the BSL-4 pathogens. These modules are designed to provide a nurse, emergency medical technician, or critical care physician with critical information that is quickly accessible as well as an extensive discussion of all aspects of the agent. The modules are in a standard format with extensive references and websites for further reading. All of this information is available for review any time both in hard copy as well as on the hospital's intranet site in the form of slide presentations, videos, or PDF files. The SPH staff has been generous in supplying feedback on the training and has been instrumental in refining the curriculum. Acquisition of knowledge has been documented with the use of pretesting and posttesting. After completion of the training, SPH staff members expressed increased confidence in caring for patients with all types of communicable infectious diseases, including VHFs.

To maintain readiness, a series of drills and exercises have been performed and will continue, in collaboration with RML and local emergency medical services providers. These readiness exercises have encompassed all aspects of care from arrival to the hospital through discharge.

Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2010;16(3) © 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Cite this: Preparing a Community Hospital to Manage Work-related Exposures to Infectious Agents in BioSafety Level 3 and 4 Laboratories - Medscape - Mar 01, 2010.

Comments