Last month, GM unveiled its GMC Hummer EV along with a stunning video featuring the electric truck speeding across salt flats, climbing over boulders and driving diagonally – or “crab walking” – through canyons.

The only thing is that it wasn’t a real Hummer EV at all.

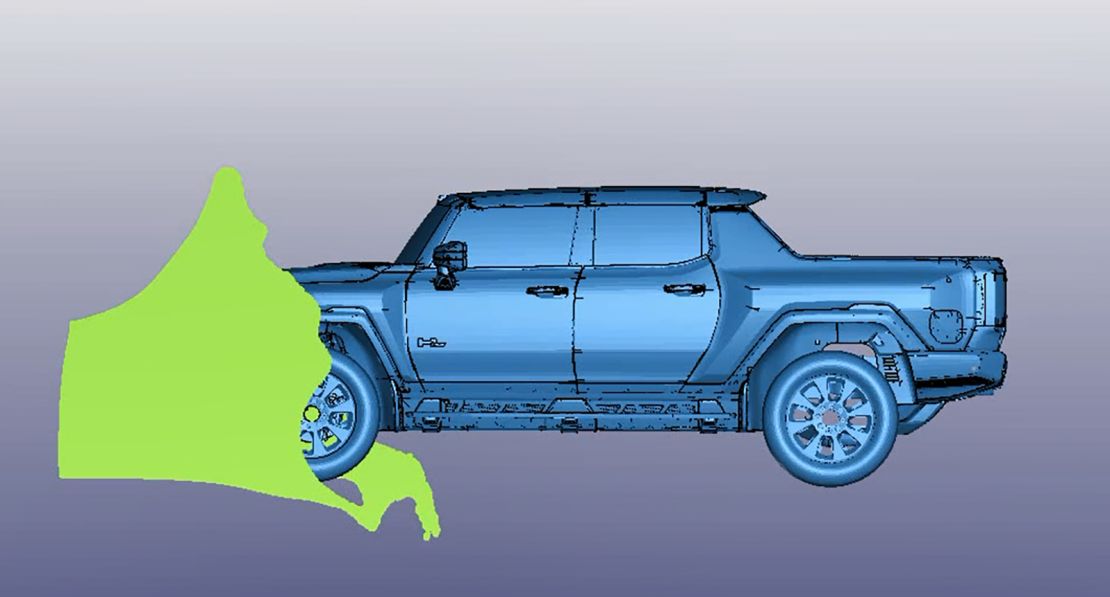

What viewers saw was a combination, in various shots, of computer animation and life-sized mock-ups of the truck with low-powered electric motors. If you had looked really closely you might have seen the disclaimer text in the corner of the screen: “Simulated vehicle shown.”

A real Hummer EV wasn’t used in the ad because there aren’t any real Hummer EVs yet. As a general rule, the process of designing and making a mainstream car has typically taken about five years. With only a year to go before production is expected to start, GM is only now starting to build fully working prototypes of the electric truck.

But GM executives don’t seem too concerned. This is not a matter of last-minute scrambling, GM executives say, but part of an overall shortened time frame for the entire vehicle development process. In the case of GM’s new 1,000-horsepower Hummer EV, engineers say they have cut the time down to just two years.

As a result, the company claims to be saving about $1.5 billion annually in company-wide product development costs compared to just a few years ago. That amount is part of a targeted $4.5 billion in overall cost savings GM had previously announced.

The techniques and technologies GM is using to cut development and production costs aren’t unique to the company. But it shows how new technologies, such as virtual product testing and hardware-in-the-loop tests, which mixes computers and machines, are speeding up what had long been a slow and expensive process.

Testing in the virtual world

In the case of the Hummer EV, there were a few things that also helped shorten the process. Since it’s a fully electric truck, for example, it’s mechanically much simpler than a gasoline-powered vehicle involving a complex engine, transmission and mechanical four-wheel-drive system.

GM had been working on the Ultium battery system underlying the Hummer for a while before this particular model was dreamed up. So having an existing electric vehicle architecture helped.

Also, the essential goal of the Hummer EV, was straightforward: to create “a legit off-road vehicle,” said Michael Colville, one of the lead engineers working on the project. That’s much easier, and faster, to work toward than creating a mass-market vehicle with competing goals for desirability and practicality. With a typical crossover SUV, for instance, engineers and designers are constantly pitting things like sportiness and a cool design against practicality, fuel economy and comfort.

But computing power will also play a huge part in the Hummer’s quick turnaround. And it’s something that impacts all modern vehicle development – electric or not. Not all vehicle design programs will be as short as the Hummer’s, but they can be shorter, according to GM engineers.

Engineers and designers can now design parts virtually before they actually have to produce them. That way they can see how reshaping the piece or making it from different materials would effect performance and weight without having to actually make it first.

It’s the sort of technology automakers are relying on more and, with the advent of electric vehicles, there get to be more common components between models, said Sam Abuelsamid, an analyst with the consulting company Guidehouse.

“Once they get those fundamental bits aligned, it gives you a lot more flexibility for what [type of vehicle body] you want to put on top of it,” he said, “then I think we’ll see everybody doing this.”

Testing virtual parts has allowed GM to drastically cut the number of 3D-printed prototype parts – which can cost 10 to 20 times as much as a mass-produced part, said Jim Hentschel, GM’s global vice president for safety systems and integration.

As a result, GM now spends less than half of what it did in 2018 on prototype parts, Hentschel said. The time spent testing parts has, likewise, been cut in half, he said.

Also, far more tests can be run virtually than using real parts and vehicles. That can sometimes uncover issues that previously might not have been discovered until late in the development process – when fixing them would have been difficult and costly.

For example, to test skid plates, which protect parts underneath an off-road vehicle’s body from damage, engineers would usually drag the vehicle across rocks. Reinforcements would then be added or weak spots in the plates would be thickened, an expensive process that involves making new metal stampings. For the Hummer EV, engineers used virtual testing. They were able to refine the skid plate design without having to make and test new plates.

It’s also become much easier to collect detailed data from virtual tests, said Hentschel. With virtual crash tests, for instance, engineers can study how individual parts of the car, including parts deep inside, performed on impact in enormous detail, he said.

In some cases, the computer software itself can “learn” from tests and make its own changes in the virtual models. The tests can then be run again with the new “parts” and the computer can gauge the results of its own work. This machine learning approach has been used to engineer fasteners that hold on interior door panels, Hentschel said. Tens of thousands of virtual door slams helped to make sure the fasteners wouldn’t break with changes and improvements made along the way.

“We were able to automate how that engineer thinks, and basically do all that in an automated fashion significantly quicker, and with significantly fewer errors than if the engineers had to do it all themselves,” Hentschel said.

Combining virtual and real

Still, automakers need to take great care when relying on virtual rather than real testing, Abuelsamid said. There can’t be any surprises when the real parts are eventually put through a real test.

“If you’re going to simulate things, your simulation models have to have a very high degree of fidelity,” he said, “so the results from simulation match the results that you’re going to get if you were to do a physical test of the same component or same system.”

When that time comes, computers can be connected to physical test beds to create so-called hardware-in-the-loop systems. Systems like this were used to test motors, batteries and braking systems for the Hummer EVs, Colville said.

With computers monitoring the tests and collecting data, tests can be run continuously day and night. Engineers can check results and alter the tests remotely from home, which helped work to continue throughout the Covid shutdowns

Human test drivers were able to use virtual-reality systems that emulated the sensations of driving a Hummer EV long before the first prototype trucks have even been built. The first complete prototype Hummers are only now being assembled and are expected to be finished soon, a GM spokesman said.

Software settings on the VR test drive system can even recreate the experience of driving on wet roads, on soft sand or through mud. Changes can be made to the virtual truck’s suspension, tires and other systems as a result.

“We know how the truck is going to feel, physically, before we’ve actually put a truck on the road,” said Colville, who noted that the same VR system was used on the latest Corvette.

Test drivers at other car companies, including Ferrari, use similar systems before prototypes are ready. The driver sits inside a large box with seats, a steering wheel and pedals. Large video screens provide a lifelike view of terrain or roads. The box sits on a platform that tilts from front to back and side to side to mimic the g-forces of accelerating, braking and cornering while shaking and bouncing to mimic bumps. The effects are amazingly lifelike, according to test drivers who’ve used the systems.

Testing in the real world can’t be put off forever, of course. That’s why GM is building real Hummer EV prototypes now. Winter is coming, and they need to get out there for cold weather testing in real snow.

“In the end, I don’t sell a virtual product, I sell a real product,” said Hentschel, “and so we’ve got to make sure that everything we did virtually does, in fact, come true.”