Key Points

Having read this article, the reader will:

-

Appreciate the challenges presented by a flabby ridge when constructing complete dentures.

-

Understand the various techniques and materials available when making suitable impressions of edentulous ridges containing flabby tissues.

-

Be able to make a suitable impression of a flabby ridge using contemporary materials.

Abstract

The presence of displaceable denture-bearing tissues often presents a difficulty when making complete dentures. Unless managed appropriately, such 'flabby ridges' adversely affect the support, retention and stability of complete dentures. Many impression techniques have been proposed to help overcome this difficulty. While these vary in approach, they are similar in their complexity, are often quite time-consuming to perform, and rely on materials not commonly in use in contemporary general dental practice. The purpose of this paper is to describe an impression technique for flabby ridges that makes use of polyvinylsiloxane impression dental materials routinely available in general dental practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The performance of a complete denture is often a reflection of its support and retention.1 A master impression for a complete denture should 'record the entire functional denture-bearing area to ensure maximum support, retention and stability for the denture during use'.2 However difficulties arise when the quality of the denture bearing areas are not suitable for this purpose. Displaceable, or 'flabby ridges', present a particular difficulty and may give rise to complaints of pain or looseness relating to a complete denture that rests on them.3 Published studies indicate that the prevalence of flabby ridges can vary, occurring in up to 24% of edentate maxillae and in 5% of edentate mandibles.4,5 Historically, flabby ridges found in the anterior maxilla were a feature of the 'combination syndrome'.6,7 In this 'condition', the flabby ridge was thought to occur as a result of a maxillary complete denture opposing mandibular anterior natural teeth, without proper posterior occlusal support. Such flabby tissues could also arise as a result of unplanned or uncontrolled dental extractions.8

A variety of techniques have been suggested to circumvent the difficulty of making a denture to rest on a flabby ridge. It has been stated that while the flabby ridge may provide poor retention for a denture, it is better than no ridge — as could occur following surgical excision of the flabby tissues.4 A multitude of impression techniques have been suggested in the past to help record a suitable impression of a flabby denture-bearing area. When considering these, it is important to realise that all impressions for complete dentures could be categorised in three ways:

-

1

The mucostatic technique (non-displacive),9

- 2

-

3

The selective pressure impression technique — where some denture bearing tissues are displaced, and others are not.12

A mucostatic impression technique9 records the un-displaced denture bearing areas at rest. As the resultant denture is more closely adapted to the underlying tissues at rest, it is theoretically more retentive. However, occlusal forces will not be evenly distributed across the underlying denture bearing area. In contrast, a mucocompressive impression technique10,11 compresses the underlying tissues in a manner similar to the way in which the resultant denture will compress the underlying tissues. In this fashion, the resultant occlusal forces will be more evenly distributed across the denture bearing tissues. While there is much speculation in the dental literature regarding the most suitable impression technique for a complete denture, there is no evidence to indicate that one technique produces better long-term results than the other.12 In practice, most impression techniques for conventional dentures could effectively be considered 'selective pressure' techniques.12 If close-fitting custom trays and high viscosity impression materials are used, the soft tissues at the vibrating line on the palate are compressed, while the tightly bound mucosa on the hard palate is not.13

A particular problem is encountered if a flabby ridge is present within an otherwise 'normal' denture bearing area. If the flabby tissue is compressed during conventional impression making, it will later tend to recoil and dislodge the resulting overlying denture.3 Clearly, an impression technique is required which will compress the non-flabby tissues to obtain optimal support, and, at the same time, will not displace the flabby tissues.

A multitude of impression techniques have been described for overcoming the problem of the flabby ridge. Liddlelow14 described a technique whereby two separate impression materials are used in a custom tray (using 'plaster of Paris' over the flabby tissues, and zinc oxide and eugenol over the 'normal' tissues). Osborne15 described a technique whereby two separate impression trays and materials are used to separately record the 'flabby' and 'normal' tissues, and then related intra-orally. Watson16 described the 'window' impression technique where a custom tray is made with a window or opening over the (usually anterior) flabby tissues. A mucocompressive impression is first made of the normal tissues using the custom tray and zinc oxide and eugenol. Once set, it is removed, trimmed, and re-seated in the mouth. A low viscosity mix of 'plaster of Paris' is then painted onto the flabby tissues through the window. Once set, the entire impression is removed. Each of these techniques might be considered cumbersome, and the difficulties associated with their manipulation could lead to inaccuracies. Watt and McGregor17 — recently revisited by Lynch and Allen18 — described a technique where impression compound is applied to a modified custom tray. The thermoplastic properties of this material are then manipulated to simultaneously compress the 'normal tissues', while avoiding displacement of the 'flabby tissues' using the same material and impression tray. Over this manipulated impression compound, a wash impression with zinc-oxide and eugenol is made. While this final impression technique is clearly less complex that the previous three described, the problem with all four techniques is that they rely on materials such as 'plaster of Paris', impression compound, and zinc-oxide and eugenol. Many general dental practitioners now rely on 'newer', more 'easy-to-use' materials, such as polyvinylsiloxanes (silicones), particularly for fixed prosthodontics.19,20

The purpose of this paper is to describe an impression technique for making impressions of denture bearing areas containing flabby ridges, which uses a simplified technique and more widely used impression materials.

Clinical report

A 62-year-old female was referred by her general dental practitioner to the Department of Restorative Dentistry of the Cork University Dental School and Hospital, (Cork, Ireland) for specialist treatment regarding her prosthodontic rehabilitation. The patient reported that she had recently been provided with a maxillary complete denture, which she described as 'loose'. This was her second complete maxillary denture since being rendered edentulous five years previously and she had found both unsatisfactory. On examination, the patient was partially dentate, with no teeth present in her maxilla, and 12 teeth present in her mandible (Fig. 1). It was noted that there was an extensive area of flabby tissue present on the anterior region of her maxillary denture bearing area.

Following discussion with the patient regarding the available treatment options, it was clear that she was anxious to avoid surgical procedures such as implants. It was decided to provide her with a new maxillary complete denture, paying attention to the impression technique, and to appropriately design the occlusal scheme.

A primary impression of the maxillary denture bearing area was made with a low viscosity irreversible hydrocolloid material ('Alginate'; Dentsply Ltd-UK, Weybridge, Surrey, UK), to ensure minimal distortion of the displaceable ('flabby') tissues. The impression was poured in dental stone. The displaceable areas were identified on the cast (Fig. 2). Three uniform thicknesses of dental wax ('Doric Toughened Wax'; Davis Schottlander and Davis Ltd, Herts, UK) were placed as a 'spacer' over the displaceable areas identified on the cast and one thickness over the remaining non-displaceable areas. The custom tray was fabricated in the usual manner. Following fabrication, the custom tray was perforated over the areas of the primary cast representing the flabby tissues (Fig. 3).

At the chair-side, the custom tray was inserted into the mouth and any over-extended areas of the periphery were reduced. The master impression was then made as follows:

After application of a suitable adhesive, heavy bodied addition-curing polyvinylsiloxane (Extrude® polyvinylsiloxane impression material; Kerr, Romulus, MI, USA) was applied to the area of the custom tray associated with the 'normal' tissues. Once set, it was removed from the mouth.

Using a scalpel, any material that had flowed into the area of the tray associated with 'flabby' tissues was removed. Heavy bodied impression material was then applied to the periphery of the custom tray. This was placed in the mouth, and the heavy bodied polyvinyl siloxane was border-moulded in the usual manner. Once this had set, the tray was removed from the mouth (Fig. 4).

The area of the custom tray associated with the 'flabby' tissues was then filled with light bodied polyvinylsiloxane impression material. A wash of light-bodied polyvinylsiloxane impression material was also placed over the heavy bodied material that had compressed the 'normal' tissues. This tray was placed in the mouth and allowed to set.

Once set, the impression was removed from the mouth and inspected (Fig. 5). Any excess material was removed. The impression was re-inserted to ensure that it was retentive and did not rock when pressure was applied over the displaceable areas. Caution is advised with the use of polyvinylsiloxane impression materials, as inaccurate manipulation can lead to over-extension of the impression.

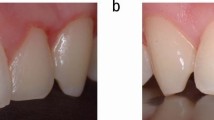

The impression was cast in dental stone, paying careful attention to preserving the bordered moulded sulcus area. A heat-cured acrylic transparent baseplate was fabricated to assess the accuracy of fit. Denture fabrication then continued in the usual manner. Following face-bow transfer, the technician was instructed to arrange the teeth on a semi-adjustable articulator (Denar Anamark Fossae; Teledyne Water Pik), achieving balanced articulation, and paying attention to even tooth contact in excursive movements. The dentures were delivered, and at subsequent review appointments the patient reported satisfaction with stability, aesthetics and function (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The profile of patients who present for complete dentures, or replacement complete dentures, is now more aged than it was 30 years ago.21,22 As a result of advances in dental techniques and dental treatment philosophies, more patients retain some, or all, of their natural teeth until later in life.23 Sometimes, unusual arrangements of remaining natural teeth can lead to unfavourable distribution of occlusal forces on residual alveolar ridges, resulting in bone resorption and development of flabby tissues. As a result of accompanying medical conditions or medical treatments such elderly patients may be unsuited for surgical procedures such as removal of flabby ridges, bone grafting, or placement of dental implants. The description of this new impression technique is therefore timely. It describes how the management of poor denture-bearing areas can be accomplished by expanding on the basic principles of complete denture construction without recourse to surgically invasive procedures.

A presenting complaint of a complete denture that has been made for a flabby ridge, without proper care being taken to avoid compressing the flabby tissues, is that the denture 'is loose'. A common approach to solving a 'loose' complete denture is to apply some chairside reline material.3 It will be appreciated that this approach is inappropriate and will not solve the problem — the complete denture will act as a custom tray, and with the viscous chairside reline material will further displace the flabby tissue. The tissues will once again tend to recoil and the denture will still be 'loose'.

The technique described does not involve extra clinical stages in the construction of a complete denture, thereby keeping clinical time to a minimum. The impression technique can be accomplished relatively quickly, and uses materials with which the general dental practitioner is already familiar. There is no need for the practitioner to apprehensively use materials that they may have little experience of using. Polyvinylsiloxanes are dimensionally stable and do not need to be poured immediately. They are also less brittle than 'plaster of Paris' and do not need to be handled as carefully.3

Other treatment modalities for the scenario described in this article include surgical 'debulking' or excision of the flabby tissues, and the use of dental implants. Surgical 'debulking' of flabby tissues is mainly a historical concept nowadays. The rationale behind its use was that removal of flabby tissues would result in a 'normal' compressible denture bearing area on which a mucocompressive impression technique could be used. Some of the difficulties caused by this approach include the fact that many complete denture patients are elderly or have complex medical histories, for which any form of surgery is contraindicated. Furthermore, the excision of flabby tissues and resultant 'shallow' ridge may provide little retention or resistance to lateral forces on the resultant denture. One is reminded of the concept that prosthodontic therapy should be concerned with the 'conservation of what remains, rather than the meticulous replacement of what has been lost'.24 The use of dental implants in this scenario is also not without difficulty. It is clear that if there has been excessive bone resorption and replacement by flabby tissues, then there will be little bone remaining into which dental implants can be placed. While it would be technically possible to augment the remaining ridge with bone grafts, the prognosis of such treatment would be questionable. Furthermore, there are a group of patients who for a variety of clinical or medical reasons are unsuited for dental implant treatment. There are also some patients who do not wish to have surgically invasive procedures such as placement of dental implants.

It is worth noting two further items from the technique described. Firstly, after completion of the master impression, it is crucial to ensure that the occlusal plane is properly orientated, and that a suitable occlusal scheme with proper balancing contacts in excursive movements is achieved. The use of a face-bow transfer and arrangement of the teeth on a semi-adjustable articulator can facilitate this. It is important to realise that an incorrectly oriented occlusal plane, or incorporation of displacing occlusal contacts, will further destabilise a denture that is relying on poor quality denture-bearing tissues.25 The efforts to secure an adequate impression will have been wasted. Secondly, the use of a transparent acrylic heat-cured base permits rapid assessment of the accuracy of the impression technique. Using a transparent base allows rapid visualisation of the adaptation of the base to the underlying denture bearing areas. Ingress of air can be rapidly noticed, and movement of the base can be observed in association with specific movements.

Conclusion

This paper has described an impression technique for management of a denture bearing area that contains flabby tissues. The materials used are readily available and used in contemporary general dental practice. The technique does not require additional clinical visits compared to fabrication of a conventional complete denture. The time required for the specialised impression technique is not excessive. This technique can be readily completed by the general dental practitioner, allowing flabby ridge complete denture cases to be managed in a primary dental care setting.

References

Fenlon MR, Sherriff M, Walter JD . Comparison of patients' appreciation of 500 complete dentures and clinical assessment of quality. Eur J Prosthodont Rest Dent 1999; 7: 11–14.

The British Society for the Study of Prosthetic Dentistry. Guidelines in prosthetic and implant dentistry. London: Quintessence, 1996.

Basker RM, Davenport JC . Prosthetic treatment of the edentulous patient. 4th edn. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002.

Carlsson GE . Clinical morbidity and sequelae of treatment with complete dentures. J Prosthet Dent 1998; 79: 17–23.

Xie Q, Nähri TO, Nevalainen JM et al. Oral status and prosthetic factors related to residual ridge resorption in elderly subjects. Int J Prosthodont 1997; 55: 306–313.

Kelly E . Changes caused by a mandibular removable partial denture opposing a maxillary complete denture. J Prosthet Dent 1972; 27: 210–215.

Lynch CD, Allen PF . The 'combination syndrome' revisited. Dent Update 2004; 31: 410–420.

Allen PF, McCarthy S . Complete dentures from planning to problem solving. London: Quintessence Publishing, 2003.

Addison PI . Mucostatic impressions. J Amer Dent Assoc 1944; 31: 941.

Fournet SC, Tuller CS . A revolutionary mechanical principle utilised to produce full lower dentures surpassing in stability the best modern upper dentures. J Amer Dent Assoc 1936; 23: 1028.

Applebaum EM, Rivette HC . Wax base development for complete denture impressions. J Prosthet Dent 1985; 53: 663.

McCord JF, Grant AA . Impression making. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 484–492.

Jacob RF . The traditional therapeutic paradigm: Complete denture therapy. J Prosthet Dent 1998; 79: 6–13.

Liddelow KP . The prosthetic treatment of the elderly. Br Dent J 1964; 117: 307–315.

Osborne J . Two impression methods for mobile fibrous ridges. Br Dent J 1964; 117: 392–394.

Watson RM . Impression technique for maxillary fibrous ridge. Br Dent J 1970; 128: 552.

Watt DM, MacGregor AR . Designing complete dentures. 2nd edn. Bristol: IOP Publishing Ltd, 1986.

Lynch CD, Allen PF . Management of the flabby ridge: re-visiting the principles of complete denture construction. Eur J Prosthet Rest Dent 2003; 11: 145–148.

Lynch CD, Allen PF . Quality of written prescriptions and master impression for fixed and removable prosthodontics: a comparative study. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 17–20.

Lynch CD, Allen PF . Quality of communication between dental practitioners and dental technicians for fixed prosthodontics in Ireland. J Oral Rehab 2005; 32: 901–905.

O'Mullane D, Whelton H . Oral health of Irish adults. Dublin: The Stationary Office, 1992.

Kelly M, Steele J, Nuttall N, et al. Adult Dental Health Survey — Oral Health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: The Stationary Office, 2000.

Woolfardt JF, Han-Kuang T, Basker RM . Removable partial denture design in Alberta dental practices. J Canad Dent Assoc 1996; 62: 637–644.

DeVan MM . The nature of the partial denture foundation: Suggestions for its preservation. J Prosthet Dent 1952; 2: 210–218.

Carr AB . Single complete dentures opposing natural or restored teeth. In Zarb G A, Bolender C L, Carlsson G E (Eds). Boucher's prosthodontic treatment for edentulous patients. 11th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 1997.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lynch, C., Allen, P. Management of the flabby ridge: using contemporary materials to solve an old problem. Br Dent J 200, 258–261 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813306

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813306

This article is cited by

-

Complicating factors in complete dentures: assessing case complexity

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Five steps to flabby ridge success

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Novel rechargeable calcium phosphate nanoparticle-containing orthodontic cement

International Journal of Oral Science (2017)

-

Clinical evaluation of final impressions from three-dimensional printed custom trays

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

A randomised controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention delivered by dental hygienists: a feasibility study

BMC Oral Health (2007)