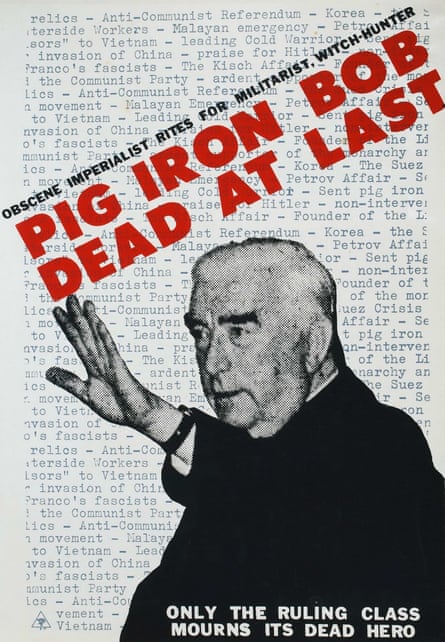

Forced to move house during the lockdown – legally, I might add, as lifting boxes was mercifully classified as an essential service – I stumbled across an old poster that seemed eerily in tune with the times. The poster had been plastered around inner city Melbourne in late 1978 in the days after Sir Robert Menzies died. “Pig Iron Bob Dead At Last” the headline blared. A smaller strap across the top read: “Obscene Imperialist Rites for Militarist Witch Hunter”. A bushy-browed Menzies was shown waving his right arm, an image that had been cropped to give it a whiff of a Hitlerian salute.

Looking afresh at the poster after so many years, my first instinct was to admire the agility of its North Korean-style invective, vituperative insults and historical fury all jammed into a few words. It was only a few days later, when one of Menzies’s Liberal party successors, Scott Morrison, got to his feet at the Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra for the country’s annual defence strategic update that the full extent of its modern resonance hit me.

Speeches like the one delivered by Morrison are designed to peer over the horizon to threats that look uncertain and unformed today, but could materialise into something serious in decades to come. Morrison was anything but vague in his depiction of the coming storms in the Indo-Pacific. He went back to the future for guidance, mentioning the 1930s four times. It’s an era, he said, that he’d been “revisiting on a very regular basis, and when you connect the economic challenges and the global uncertainty, it can be very haunting”.

A cartoonist illustrating a column about the speech drew the prime minister looking in the mirror and seeing Winston Churchill. Much as Morrison might have been thrilled, the comparison struck a lazy note for me, with, in the apparent absence of a local hero, a touch of cultural cringe as well.

Before Covid-19, before the first wave of mysteriously stricken patients began to crowd into hospitals in Wuhan, and the lies and the chaos and the lockdowns that followed as the virus spread out from the giant inland city to the rest of China and then overseas, I used to make lists of all the things that Australia and China were battling over. Cyber attacks, Taiwan, the South China Sea, Huawei, the Pacific Islands, Hong Kong, foreign interference, universities, Xinjiang, Australian prisoners held in China, Crown casinos, and a multitude of spying allegations. As soon as one issue dropped off the front pages, another one rushed to take its place. Even the two countries’ sports stars were fighting, with champion swimmer Mack Horton accusing his rival, Sun Yang, of being a drug cheat.

The virus lifted the mutual acrimony to a new level. In Canberra’s telling, the Australian government’s call for an independent investigation into Covid-19 was an entirely reasonable response to a pandemic that had cratered the global economy. In Beijing, the Foreign Ministry denounced it as a “political manipulation” made at the behest of Washington. Or, as one Chinese netizen put it, Australia was “this giant kangaroo serving as a dog of the US”. Beijing announced trade sanctions on beef and barley to drive home its displeasure. Both nations warned their citizens that traveling to each other’s countries was dangerous. It didn’t really matter, as no one could travel anyway, but in terms of political signalling, it was potent. This was a relationship headed downhill fast.

To get a sense of just how bad things might get, let’s go back to Australia’s longest serving prime minister, and the disrespectful send-off that some old-fashioned socialists in Melbourne provided for him in 1978.

Menzies was given the nickname “Pig Iron Bob” by waterside workers in 1938. They were protesting against the sale of pig (crude) iron to Japanese steelmakers, which Menzies, as the then attorney general, forced through in the face of industrial action. Coming just after the Imperial Army’s massacre of Chinese in Nanjing, the waterside workers objected to Australian resources being used to feed the Japanese war machine. In that respect, the “Pig Iron Bob” posters didn’t make sense. Far from being a “militarist”, the criticism of Menzies was that he hadn’t, at that point, been hawkish enough. Nonetheless, once the Pacific war was under way and Australian troops were on the frontline battling the Japanese, many conservatives, with the benefit of hindsight, came to sympathise with the communist union. Menzies himself, on the left at least, struggled to live the nickname down.

These days, the Australian government has a close relationship with Japan and views China as the major threat to peace and stability in the region. This, by the way, drives Chinese diplomats in Australia around the bend. It doesn’t take long once you meet for them to remind you that China and Australia were allies in the Pacific war. That’s certainly true, though the diplomats don’t like to be reminded in turn that Australia was allied at the time not with Mao Zedong’s communists, but Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, who, after losing the civil war, fled to Taiwan, an island which remains unfinished business to this day. The diplomats also seem blind to the fact that China under Xi Jinping has much in common these days with the Japan of the 1930s.

But back to pig iron, which, like iron ore, is an essential ingredient in making steel. Luckily for Australian resource companies, and the Treasury, which collects taxes from them, China’s economy is still heavily reliant on building things which use steel. Even though its share of global of economic output is about 20%, China makes more than half of the world’s steel. As a journalist based in Tokyo in the 1990s, I had to track the annual iron ore price negotiations between Australian miners and Japanese steel mills, at that time by far our biggest customer. Analysts in Tokyo and around the world would pore over the latest signs from local steel mills of an uptick in production, which at that time averaged in total about 100m tonnes a year. Anything more would be a bonanza for the miners. China, however, has reached into another dimension. It is making nearly 1bn tonnes of steel a year, to build new cities and infrastructure, 10 times what Japan used to produce.

For a country like Australia, located nearby and sitting on huge reserves of high-quality resources, China’s steel boom has been a once-in-a-lifetime windfall. China is Australia’s biggest export market, and iron ore sales comprise the biggest component of that. Even as the pandemic persisted in much of the world, Australian iron ore exports were reaching record levels in 2020 as China’s economy recovered and steel production along with it. The shiploads leaving Western Australia for ports along China’s east coast have been fetching fat prices too, as production from mines in Brazil, Australia’s main competitor, were disrupted by accidents and the coronavirus.

So, when Morrison looks in the proverbial cartoonist’s mirror, does he worry that one day, instead of seeing a wartime hero like Churchill looking back at him, it will be a prewar Menzies in his place? In other words, does he worry that China’s relations with the west will become so bad that his job as prime minister will be not to reap the benefits of iron ore sales, but instead face the prospect that he might have to restrict them? “Steel Scott”, anyone? I know it doesn’t have quite the same stench as “Pig Iron Bob” but it could take on a more sinister ring in the hands of a skilled political opponent.

Morrison has hardly discouraged such hyperbole. After his speech at the defence academy, he told the Sydney Morning Herald that he had deliberately thrown in those multiple references to the 1930s because he thought the Australian people weren’t sufficiently aware of the potential dangers ahead. “That’s why I thought it was important to stress the point,” he said. Morrison wasn’t just thinking of the end of that decade, but its opening years as well, which ushered in the Great Depression and a sustained economic downturn, which in turn contributed to the conditions which created the world war that followed.

Before Covid-19, such grave historical references wouldn’t have passed the laugh test. Slow the sales of our single most valuable export, at a time when we need economic growth and tax revenues more than ever? But don’t think that the idea of Canberra interrupting iron ore sales to China hasn’t crossed the minds of senior executives in the C-suites of our big miners. Nor have the Chinese missed the signals themselves, which is why they are focused on securing alternative suppliers for core industrial resources, by reviving iron ore mines in Guinea, West Africa, as well as cultivating closer ties with Brazil.

Naturally, the high-stakes debate over China lends itself to extremes. On either side of this debate, accusations that single out individuals as either warmongers or traitors are commonplace these days. The debate has been transformative in other ways, too. After decades in which the idea of strong government has been under sustained ideological attack in many western countries, state power and state capacity are back in vogue.

China, of course, never bought into the small government movement and has always been committed to building and maintaining a powerful state. After mishandling the start of Covid-19 in Wuhan, the Communist party in China clicked into gear at a frightening tempo to bring the virus under control. Without the need for any messy, democratic debate about civil rights or so forth, the government was able, almost overnight, to lock down more than 700 million people in residential detention; seal provincial, city, county and village borders; shut factories while commandeering the entire output of some businesses to supply emergency medical equipment; order the wearing of masks; mobilise military and paramilitary units; build pop-up hospitals; mandate testing of tens of millions of citizens; and track the movements of residents using mobile phone apps. The mobilisation of the state, businesses, and people at such short notice was a potent reminder that the ruling party has virtual war powers at its fingertips in any declared emergency, even in the absence of conflict with a foreign power.

The conservative Morrison government has had to embrace the state in Australia during Covid-19 and try to plug gaps in strategic industries, with little thought for budget deficits, all very much the hallmarks of a wartime administration. Australia also created a national cabinet to manage the crisis. China, of course, as a single-party state, has had one all the time.

For some, the idea of perpetual conflict with China, overlaid by the miseries of Covid-19, is an exhausting prospect. For others, the prospect of standing up to China looms as an exhilarating, clarifying experience. The response of some Australian politicians to the China challenge, and their enthusiastic, unyielding belief that Australia has reached a historic turning point, reminds me of the way that friends of the late Christopher Hitchens tried to explain the hitherto leftwing polemicist’s fervent support for George W Bush’s 2003 Iraq war. “He’s always looking for the defining moment, as it were, our Spanish civil war, where you put yourself on the right side, and stand up to the enemy,” one of Hitchens’s friends, the writer Ian Buruma, told the New Yorker. Hitchens himself foresaw “a war to the finish between everything I love and everything I hate”, and a question on which history would judge him.

Andrew Hastie, the Liberal backbencher and chair of the intelligence committee, is one case in point. He arrived in Canberra with the views that you might expect of a veteran of the special forces’ mission in Afghanistan: believing the so-called war on terror spawned by the 11 September attacks to be the paramount challenge of the 21st century. But learning about China has been a gamechanger for Hastie. He has come to see Xi Jinping as a latterday Joseph Stalin, and Australia as complacent as France before the Nazi invasion – and that was before Covid-19.

The likes of Morrison – and Hastie – have made up their minds about which direction the world is heading. They see themselves as the guardians of their country and its values at a hinge point in history. Hopefully, their strategy of standing tough alongside allies against China, which is one that you see emerging around the developed world, will deter the rising superpower.

Otherwise, we can only hope they are wrong about China. It is all very well to want to look in the mirror and see Winston Churchill staring back at you. Churchill was certainly a hero, but only after one of the most destructive wars in history.