How a Jewish collector rescued his ‘degenerate art’ from the grasp of the Nazis

4 October 2016

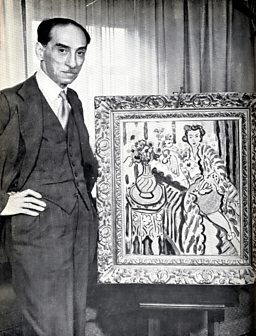

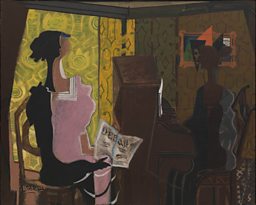

Including works by Picasso, Braque, Renoir, and Matisse, the astonishing collection of Jewish art dealer Paul Rosenberg was declared ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and duly confiscated. With a plot worthy of Hollywood, the Free French Army thwarted this act of cultural vandalism and helped preserve the collection for posterity. WILLIAM COOK visits a new exhibition of Rosenberg’s remarkable artistic treasures.

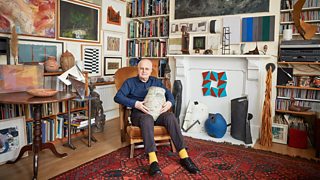

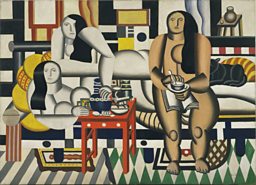

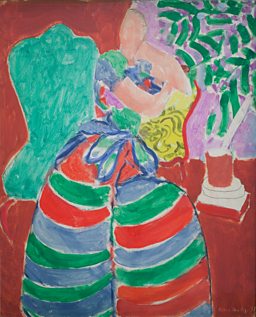

Modern art never would have taken off without the dealers who promoted it, and here in Liege, the Boverie Museum is hosting a lavish exhibition devoted to one of the most influential art dealers of modern times. Paul Rosenberg championed Matisse, Braque, Leger and Picasso. As this fascinating show reveals, his life story encapsulates the evolution of modern art.

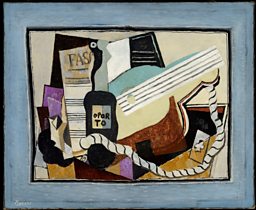

Rosenberg was born in Paris in 1881, the son of a Jewish antique dealer. He started working for his father when he was 16 and quickly acquired a love of art. In 1910 he opened his own gallery, at 21 Rue La Boétie in Paris. At first he dealt in Impressionists, but he soon started working with Braque and Picasso, who’d pioneered Cubism in Paris. Rosenberg was a tireless promoter of their groundbreaking work.

As a Jewish dealer in ‘degenerate’ art, Rosenberg was a marked man

Rosenberg was passionate about modern art, but above all he was a skilful salesman. He hung George Braque and Picasso alongside pleasant Impressionists like Renoir, and established artists like Delacroix. His conservative customers were reassured by these familiar names. It made Cubism seem respectable. Rosenberg made modern art mainstream.

Rosenberg was meticulous, innovative and energetic. He embraced modern methods of promotion: catalogues, photography, newspaper advertisements. He mounted exhibitions at a frantic pace. Within six months in 1936, he put on shows by Braque, Picasso, Seurat, Monet and Matisse.

In 1940, the Nazis invaded Paris. Hitler had condemned modern artists like Picasso as ‘degenerate.’ As a Jewish dealer in ‘degenerate’ art, Rosenberg was a marked man. He fled to America, leaving the bulk of his collection behind.

Assisted by French collaborators, the Nazis seized these priceless paintings. Some were sold, some lost forever. A few even ended up in the private art collection of Hermann Goering (one of several leading Nazis who didn’t share Hitler’s distaste for modern art). Rosenberg’s gallery was appropriated by the Gestapo as a centre for Anti-Semitic ‘research.’

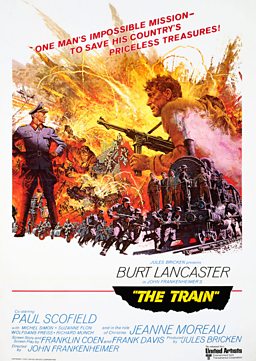

In 1944, with the Allies closing in on Paris, the Nazis packed hundreds of Rosenberg’s paintings onto a train to Germany. This train was hijacked by the Free French Army, and this precious haul was saved. One of the soldiers who stormed the train was Rosenberg’s son, Alexandre. This incident became the inspiration for the classic war film, The Train.

In 1944, with the Allies closing in on Paris, the Nazis packed hundreds of Rosenberg’s paintings onto a train to Germany

After the war, Paul Rosenberg toiled ceaselessly to reassemble his collection. About 400 paintings had gone missing. Eventually, laboriously, he retrieved over 300.

This exhibition features some of the many paintings he bought and sold, throughout his career. From Impressionism to Cubism and beyond, it’s an amazing cross-section of modern art.

Highlights include Picasso’s tender portraits of Rosenberg and his family, and Profil Bleu devant la Cheminee by Matisse, which was stolen by Goering and subsequently ended up in Oslo, until the Rosenberg family reclaimed it a few years ago.

However this show is more than just a collection of great paintings. There’s lots of interesting stuff about Rosenberg’s gallery, and his friendship with Picasso, but the best part is about the Nazi era, and the German occupation of Paris.

There’s even a recreation of the Nazis’ Degenerate Art exhibition, juxtaposing ‘Aryan’ paintings from Hitler’s art collection (not entirely without merit, but all terribly samey) with ‘degenerate’ works by German artists like Franz Marc.

These juxtapositions show that modern art is a celebration of individuality. Hitler’s ‘Aryan’ paintings could have all been painted by the same artist. Each of these ‘degenerate’ artworks is unique.

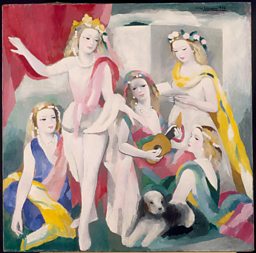

This exhibition was inspired by an acclaimed book by Rosenberg’s granddaughter, Anne Sinclair. Sinclair is an eminent journalist - she presents the French news programme 7 sur 7 (she was also previously married to former IMF boss Dominique Strauss-Kahn).

Paul Rosenberg never returned to Paris. He sold 21 Rue La Boétie. He didn’t want anything more to do with it, after what had happened there during the war

Her grandfather gave her a love of art. ‘He taught me how to look at an artwork and how to visit a museum,’ she tells me. ‘His contribution was to make the art of his artists more popular.’ He loved modern art too much to confine it to a narrow clique.

Fittingly, the last picture in this show is a painting of Anne as a little girl, by Marie Laurencin, one of her grandfather’s favourite artists. It’s a delightful portrait, but in this context it feels like more than that. It feels like a bridge between the modern world and a lost world from long ago.

Paul Rosenberg never returned to Paris. He sold 21 Rue La Boétie. He didn’t want anything more to do with it, after what had happened there during the war.

During the occupation, he’d been stripped of his French citizenship. Now he became an American citizen. He opened a gallery in New York. This new gallery introduced American collectors to modern art.

When he left for America, in 1940, Paris was still the centre of the art world. By the time he died, in 1959, the centre of the art world was New York.

More on 'degenerate' art

More art collections

21 Rue la Boétie exhibition is at the La Boverie Museum, Liege, until 29 January 2017, and then at the Pompidou Centre, Paris from February 2017.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms