We’ve got plenty of “video game movies.” Movies, like the much-maligned Super Mario Bros. or objectively-the-best-movie-ever-made Mortal Kombat, that adapt the world and characters of a video game and present a cinematic take on its narrative. What we lack are “movies about video games.” Movies that tackle one of our most important mediums of entertainment as a subject worth reckoning with, rather than more IP to plunder.

That might be why Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle was such a surprise hit. The 2017 sequel to the beloved Robin Williams-starring ‘90s classic Jumanji took that delicious premise -- what if the dangers of a board game were real? -- and updated it into the contemporary space of how we play games. In other words: What if you got sucked into a video game? And those dangers were real? Thus, beyond its blockbuster-requisite gags and set pieces (and its movie star charisma from Dwayne Johnson, Kevin Hart, Jack Black, and Karen Gillan), the film becomes a commentary about how we engage with video games as well.

In honor of the next entry in this new Jumanji meta-franchise -- Jumanji: The Next Level, which opens December 13, 2019 -- here are the best films about video games ranked. Ready to play?

Indie Game: The Movie

Indie Game: The Movie, a frank documentary, is equal parts inspiring and excruciating. Made in 2012, the film might be our best current filmed “temperature take” of contemporary video game culture. It follows the journeys of three acclaimed indie games and their eccentric developers: Super Meat Boy (Edmund McMillen and Tommy Refenes), Fez (Phil Fish), and Braid (Jonathan Blow). It’s inspiring in its insightful painting of our current generation of video game creators being raised during a peculiar time of video games. Growing up, these future creators had video games around them constantly -- but they were obviously not old enough to purchase them. Instead, they were passed down via the outside forces, like Moses with the Ten Commandments. Thus, these creators revere the force and power of video games (plastering posters over every inch of their walls) with an appealingly childlike sense of wonder and an appealingly adult sense of ambition. If you have a passion project you’ve been mulling over, Indie Game: The Movie might kickstart you into action. However: It’s excruciating in… just about every other way. Every creator is miserable. Every creator pushes themselves past their breaking points, intertwining their creations with their essences as human beings. When asked what Phil Fish will do if he doesn’t finish Fez, his response is blunt, and frankly, triggering: “I would kill myself” (When his game keeps breaking down at a later PAX panel, I can’t help but think about art imitating life). There’s an exposé-level of the unhealthiness lurking in the most fundamental parts of these all-male creators, turning Indie Game: The Movie retroactively into a warning sign for #GamerGate. Super Meat Boy codeveloper Edmund McMillen, in particular, troubles me. He seems to be in a loving relationship with his wife, Danielle. But his views on women, coupled with his desire to “push past boundaries,” seem to result in some nasty stuff. We see brief footage of one of his games (The C Word) that, to me, looks like you play as a giant erect penis in thrusting combat with a villainous, vaginal boss. This is, at best, a very, very bad extension of the “everything can be a boundary that’s pushed to an absurd joke” point of view he seems to commit to, without a bother to understand the context of its statements regarding sexual relationships between men and women. At worse, it is a game in which the way to win is to purposefully commit violent sexual assault. I relate to his (and the other creators’) struggles with feeling like an outsider, his anxieties and stomach aches and issues relating with people, his discovery of creative output as an outlet. But using pain for art is a double-edged sword. And in Indie Game: The Movie -- and in many ways, our contemporary gaming sphere -- the sword seems to swing in every direction possible.

Gamer

In one set piece late in the 2009 sci-fi actioner Gamer, Michael C. Hall does a delicious soft-shoe dance number while his goons beat the shit out of Gerard Butler. This sequence alone should, in my opinion, enter the work straight to the top of every “best of film” list ever produced, regardless of year or topic covered. Until that happens, I’ll just be over here singing the praises of Gamer as loud as I can muster. Written and directed by the maniacal Crank franchise writer/directors Neveldine/Taylor, Gamer takes a sleazy premise and filters it through the “bro-y late 2000s FPS shooters” aesthetic (think the muted, brownish colors and beefy boys holding assault rifles in games like Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare), resulting in a downright mind-numbing, eye-straining final product. And I mean this all as the sincerest of compliments. The flick takes place in 2034, where humans are addicted to a video game called Slayers (subtle, Gamer ain’t), invented by the evil Hall. One hotshot player, played by Logan Lerman, does particularly well with his avatar, who is not a programmed piece of AI but in fact a real human being played by Butler. You see, the characters of Slayers can earn their freedom if they win 30 matches in a row -- but most never do. When Hall decides Butler’s winning streak has gone long enough, flamed in part by the muckraking efforts of protesting group the “Humanz” (subtlety is overrated!), he crafts a series of new players that can cheat the system (led by Terry Crews, of course), sending Butler on the run for his life, digital or otherwise. Gamer, like the Cranks, has bonkers pieces of action, chopped and screwed by filmmakers who are more in touch with our media-saturated society’s postmodern, fast-paced ability to digest radically shifting information than perhaps any other 2000s filmmaker. Plus, a slightly increased budget and sense of narrative/visual focus ensures Neveldine and Taylor stay on track, and the relative sense of “patience” is noticeable. Beyond Hall having the most fun of his life, we also get scenery-chewing works of performative joy from eclectic actors like Ludacris and Kyra Sedgwick. Ultimately, I recommend Gamer because of its quirks and flaws. It plays like someone drank every flavor of Mountain Dew at once, read all of William Gibson’s books while someone played Gears of War in the background, did 18 suicide sprints, and then stream-of-consciousnessed out a screenplay. If Mad Max: Fury Road is praised to high-heaven for its unrelenting pace, grimy aesthetics, and crystallized, singular vision of mayhem, surely Gamer deserves some love, too.

Tron

“It’s an epic adventure that everyone will enjoy!” boasts the Disney+ blurb for Tron. I disagree. I find Tron, the Mouse House’s live-action 1982 sci-fi film, to be quite the acquired taste. Its nascent use of computer generated imagery, while deservedly regarded as revolutionary at the time, has evolved to feel like a peculiar, stiff, idiosyncratic visual choice. Its pace is slow, its screenplay is dense, its score is downright goofy, its performances are not pitched toward mainstream familial enjoyment. But that doesn’t mean I think Tron is relegated to an educational relic not worthy of a pleasurable watch. If you can get yourself on its wavelength, Tron plays like a refreshingly unorthodox Amblin flick -- like if 1980s Steven Spielberg directed a 2000s Steven Spielberg screenplay. Jeff Bridges, delivering sterling, surprisingly unaffected work as usual, plays computer programmer Kevin Flynn, consigned to live in his own video game by evil tech-corp ENCOM. He tries his best to make it back to the real world while competing with the game’s various AIs and algorithms in ways both existential (the programs are personified versions of the real-life programmers!) and physical (lightcycle and deadly techno-frisbee battles!). I’m in love with the way the digital characters look -- the result of a combination of exacting technological procedures and atypically auteur-driven stylization in the realm of visual effects. Led by Moebius, aka French comic book creator Jean Giraud, the world of the game is so peculiar -- primary colors rendered in harsh angles atop unfinished wireframe renders. The actors in the game were photographed on 65mm black and white film, footage which was then painstakingly transferred using myriad photochemical/digital processes that would take hours to complete a single frame. The result feels both charming and dangerous, digestible yet at arm’s length. In other words, Tron is perhaps our best film that spoke to the early days of video games. Is Pong going to destroy us all, enthrall us all, or both?

Tron: Legacy

When film historians talk about the 2000s/2010s’ pervasive desire to reboot past properties in newly muted, realistic, “gritty” tone, they may talk about The Dark Knight as the peak and Suicide Squad as the nadir. I just hope they take some time to give Joseph Kosinski’s directorial debut, 2010’s Tron: Legacy, more than a footnote. The film wears “gritty” like a slim-fitting, runway-ready blazer. Its colors are desaturated to pale greys and light blues, only allowing for eruptions of neon in its light cycle sequences. Oh, and its light cycle sequences move with breakneck, shockingly violent pace, using pristine cinematography from Claudio Miranda to frame each moment of the bloodsport like a cyberpunk chiaroscuro painting. Its Daft Punk score, combing the electro duo’s Human After All-era nihilistic funk with a damn symphony orchestra, straight up slaps. Tron: Legacy is the rare film that is a ton of fun to watch not despite its oppressively dark tone, but because of it (also because of Olivia Wilde’s incredibly fun performance as Quorra). But, there’s one digital elephant in the grid to discuss. Its wonky-beyond-wonkiness fully CG “young Jeff Bridges,” while especially disquieting in a flashback sequence with his child, works wonders for the film’s narrative when he becomes the chief antagonist, Clu (Codified Likeness Utility). The character contrasts visually with the lived-in, age-appropriate skin of Jeff Bridges, narratively with the conflict between malevolently efficient artificial intelligence versus stubborn human nature, and even on a meta-level. Kosinski, whose visual effects-laden commercials for Gears of War and Halo 3 earned him the keys to the Tron legacy, knows precisely how to craft thrillingly immersive CGI worlds and images into his narratives without any speed bump. Except for Bridges’ Clu, of course, which just does not look right. But Kosinski’s technological limits wind up amplifying the main thrust of the film, and of many works of speculative fiction: Human beings will always triumph over technology, because of that certain, stubborn something. Tron: Legacy thus plays as a particularly shiny, stylish reminder that at the end of the day, it’s humans who play video games, not the other way around.

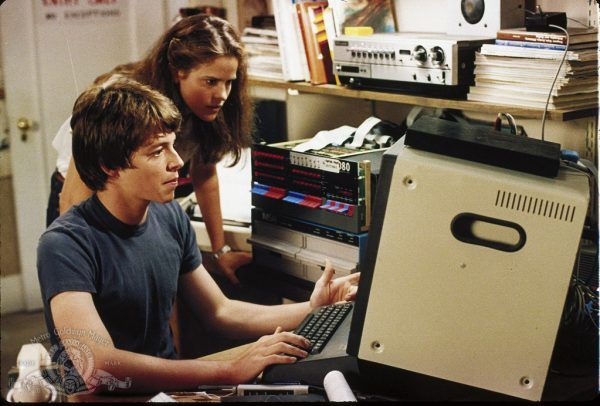

WarGames

In the summer 1983 issue of Softline, a magazine dedicated to early Apple computer news (it is well worth your reading time if you feel like a trip down memory byte lane), John Badham’s WarGames is described as being the first film that presents the presence of computers and video gaming as a given, rather than a new concept. “The film could not exist if the microcomputer did not exist as a widespread phenomenon. It takes the micro and telecommunications as a given—part of the middle-class American landscape.” Watching Matthew Broderick (charming as ever) zoom his way through seemingly complicated computer systems with ease in his fingers and mischief on his mind will ring familiar to any viewer who grew up with the Internet either as a child (Broderick) or an adult (the military officials who say things like “I don’t understand these computers very well”). Maybe younger brains are more able to instantly recognize and adapt new patterns into their lives. It could be why the cliche image of a video game player often skews younger -- the ability to instantly recognize and adapt new patterns, after all, is at the very core of games. But what if this ability is used to too much of an advantage? Against a system equally great and recognizing patterns, but without the human advantage of outside-the-pattern critical thinking? Then you’d get the delicious premise of WarGames, in which savvy hacker/gamer Broderick accidentally starts a chain of events that could lead to World War III because he -- and the military computer he hacked into -- thinks he’s playing a fun video game. If the dystopian takes on video games in Black Mirror episodes like “Bandersnatch” or “Shut Up and Dance” play too dour for you, WarGames explores many of the same themes with a lighter touch, a crackling sense of humor, and a resolution that’s as optimistic as it is existentially nerve-wracking. So much of video game culture is saturated with images of realistic violence. WarGames reminds us that real violence ain’t something to play with.

Edge of Tomorrow

If you want to know what it feels like to be a sentient video game character combined with a player, Edge of Tomorrow is likely the closest film experience you’ll get. Plopping the Groundhog Day narrative device into the world of a grimy third-person alien/military shooter, the Doug Liman-directed picture, based on acclaimed 2004 manga novel All You Need Is Kill, does one of my favorite things you can do with Tom Cruise: It makes him a damn coward. Like Magnolia before, Cruise talks a big talk in this film, hiding his lack of battlefield experience with the kind of sniveling bravado that comes from the cushy shield of a desk. But when he’s forced into battle to shoot the hell out of some aliens, he’s in for a rude awakening. And then a rude reawakening. And then a bunch more rude reawakenings in a row. You see, every time he dies, he wakes right back up and starts the battle over again. Turning his journey, effectively, into a level of a video game -- a tough, pattern-based run-and-gunner like Cuphead. We watch him learn from his mistakes, figure out where to dodge instead of standing still, feel the temporary rush of victory as he inches further toward completion, die again, respawn, and add his new lessons. Sound familiar? Along the way, he meets the incomparable Emily Blunt, his reluctant ally-turned-sage who absolutely pulverizes the alien enemies and decides to teach Cruise the basics of being an adequate soldier (think a tutorial level guide crossed with a no-bullshit take on GLaDOS crossed with your older brother who made fun of you for dying too early in World 1-1). As the two battle and rebattle and the film dives deeper into its wicked gallows sense of humor (jutted up brutally against the vicious acts of uncaring violence), the sense of “the video game playing experience” comes further and further into the film’s foreground.

Except: As the narrative gets complicated, so too does the collapsing between “player” and “character.” Cruise’s feelings of pain and frustration, while mimicking frustrations a player can have, come with an extra level of crisis due to his personally experiencing them. If you’ve ever dreamed of flying into your favorite video game, Jumanji: The Next Level might show you the dream version, and Edge of Tomorrow might show you the mordantly funny nightmare.

The Wizard

I was very, very surprised watching The Wizard. Its reputation, at least among friends who spoke to me about it, seems to be as a camp classic full of hackneyed product placement. An artifact useful only for a quick jolt of late ‘80s Nintendo nostalgia. This is what I was expecting -- nay, looking forward to -- as I started it. And yes, there are moments of the film that grind to a dead stop so we can luxuriate in the glory of Nintendo games like Super Mario Bros. 3 (which is, in fairness, a glorious game). And yes, there is a moment where a character, using the short-lived controller accessory known as the Power Glove, delivers the immortal line, “I love the Power Glove. It’s so bad.” But among all of these cheesy moments lies an almost perversely grim narrative about dysfunctional families, fathers and sons, divorce, trauma, and the damn death of a child. I am gobsmacked and awestruck by how unrelentingly dark this film wants to go.

Despite its bright, flat lighting, oft-goofy soundtrack, and remarkable kid performers, it’s all in service of (and thus in conflict with) deep, heavy stuff. And you know what? I’m glad it went there, and I feel like it pulls it all off. The Wizard’s title character is a young boy named Jimmy Woods (Luke Edwards) who suffers from a never-mentioned-by-name mental illness that might be exacerbated in part by the death of his sister. When his brother Nick (Fred Savage) discovers Jimmy is incredible at video games -- so incredible that they can make money -- they hightail it on an impromptu road trip to a video game tournament, picking up a young Haley Brooks (Jenny Lewis, who went on to be an incredible musician) along the way. And now, dear reader, I shall become very personal with you. While Jimmy’s mental illness is never named, to me it read very clearly like autism. And when I was around his age, I was diagnosed with autism. Like Jimmy, I had issues with communicating, with emotional triggers feeling like tidal waves. Like Jimmy, I found comfort in routines, traditions, and patterns -- often to the befuddlement of family and friends. And like Jimmy, the synthesis of patterns into the social fun of video games helped me immensely. Suddenly, my non-understandable needs became assets, rather than detractors. And it’s no exaggeration to say I credit my discovery of video games as a huge step in my journey toward understanding my placement on the spectrum (alongside lots and lots of therapy and self-work, which I cannot recommend enough).

Your mileage may vary in terms of representation with this film -- again, the word “autism” is never mentioned once, and I could certainly understand the argument that its “casual savantism” is an example of one of many Hollywood generalities regarding the disorder (i.e. Rain Man, The Good Doctor). But for me? I came into the film expecting a slice of goofy, video game-chasing fun. I left having seen a new favorite. In other words: I love The Wizard. It’s so bad.

The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters

A documentary, a suspense thriller, an expose, a universally David-versus-Goliath story, an exacting examination into one of the most specific subcultures we’ve got. The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters is a lot of things. Above all: It’s incredibly entertaining. Seth Gordon’s tightly structured doc dives headfirst into the world of arcade game high score competitions: specifically, for Donkey Kong, one of the most influential arcade games ever made. At the start of the film, the man holding the high score for Donkey Kong is Billy Mitchell, a man you will love to hate upon first sight. He’s a Florida-based hot sauce purveyor who boasts a scorching mullet, an American flag tie, and an oppressively cocky, downright sleazy attitude. The man challenging him is Steve Wiebe, a man you will love to love upon first sight. He’s an out of work engineer, a sweet, good-natured, quiet human, and peerlessly good at playing damn Donkey Kong (and not being a jackass about it). Or… is “peerless” not quite the right word? While the numbers achieved by Wiebe certainly seem to cement his place in gaming history, a litany of factors, from the construction of cabinet circuit boards to the validity of VHS copies to plain old human nature, complicates stuff at every turn. While, by design, The King of Kong is interested in exploring retro power structures, from the games on display to the toxic masculinity on display, it still feels like a relevant watch, a Nostradamus-esque fortune teller into the world of YouTube streaming celebs and e-sports controversies. And while the film’s ending may not provide the traditionally cathartic ending you’d desire in a story like this, do some Googling after you watch. Avoiding spoilers as carefully as I can, the bonus features of this film actually rewrote some of the film’s history. After all, it wouldn’t be a video game without DLC.

Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World

Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, the Edgar Wright-directed cult classic based on the Bryan Lee O'Malley cult classic, is not explicitly about video games. It’s explicitly about love, the past, moving on from traumas, growing up, music, and self-actualization. But this thing is drenched in video game culture, from its narrative structure to its aesthetics, in ways both simply pleasing and complicatedly dissecting. The very first image we see is the Universal logo done in a chunky, pixelated style, with their iconic theme song rendered in 16-bit synthesizers. The very second image we see is a cascading establishing shot set to an immediately familiar The Legend of Zelda establishing cue -- a nice overture to the full tune used later in a surreal dreamscape. Wright has always saturated his films, and his films’ main characters, with reverence to pop culture, and Scott Pilgrim’s (and Young Neil’s) nigh-upon idolization of the vibe of video games glows throughout, from Bill Hader’s “fighting game voiceover,” to the shifting visual language and aspect ratios of the film, to the framing structure of the entire plot. Defeat a bunch of people in a row including a “final boss” to win the love of a girl? Sounds like every golden-age video game to me. But for Wright and co-writer Michael Bacall, not everything that’s gold glitters. Scott Pilgrim’s (Michael Cera) tendencies to live life as though he’s the protagonist of a video game hamper him, stunt him, and frankly, make him seem like a selfish dick. His casual tossing aside of Knives Chau (Ellen Wong) to go after Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) is as abruptly callous as his fights against Ramona’s “evil exes.” And the film’s ending resolutions for these three characters complicate everything seen before, including (and still using) the language of video games (“Scott earned the power of self-respect!”). As a final thought: If you like this film, you owe it to yourself to play the 2010 retro side-scrolling beat ‘em up video game, which is addictive, surprisingly deep, and features an incredible soundtrack from chiptune maestros Anamanaguchi.

Wreck-It Ralph

If you’ve ever played a video game, Wreck-It Ralph is for you. If you’ve ever seen a Disney movie, Wreck-It Ralph is for you. If you’ve ever felt ostracized, if you’ve ever sought acceptance, if you’ve ever had to do something bad in order to achieve what you thought was a greater good: Wreck-It Ralph is for you. It is, in fact, for everybody, an audience-spanning comedy that reaches lofty heights among its crackerjack video game-skewering plot. The title character, voiced with painful pathos by John C. Reilly, is tired of being his video game’s villain. He wants to be a hero, to be celebrated, to win a damn medal for once. So he hops out of his game and journeys into another, meeting fellow misfit Vanellope von Schweetz (the perfect Sarah Silverman) in a Mario-Kart-combined-with-candy game. Can the two help each other find self-actualization? Wreck-It Ralph answers this question and thensome, giving its viewers the perfect blend of gags, heartstring pulls, and genuinely impressive set pieces that both spoof their genres (from gritty first-person shooters to literally sugary kart racers) and remind us how fun these genres are (seriously, I need Sugar Rush on my Switch, and I need it now). Wreck-It Ralph, while giving us the delightful Zangief, Sonic, Pac-Man, Bowser, and many other Roger Rabbit-esque cameos we need, has fundamental questions about identity on its mind, questions that lurk in the margins of every video game we’ve ever played. When we play a video game, we inhabit another character, making them do what we want to do. But what if these characters want to do something else? Worse yet -- what of the non-player characters, programmed to complete the specific, same function session after session? Can they burst free of their code and go on their own, self-made journey? Wreck-It Ralph dissects this casually existential question (in a friggin’ Disney kids’ movie!) using both Ralph, Vanellope, and a third character whom I shall not name for fear of spoilers, but let’s just say it gobsmacked me the first time I saw it. The high score has been set: Wreck-It Ralph is the greatest movie about video games ever made.