‘Digital handcuffs’: China’s Covid health apps govern life but are ripe for abuse

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

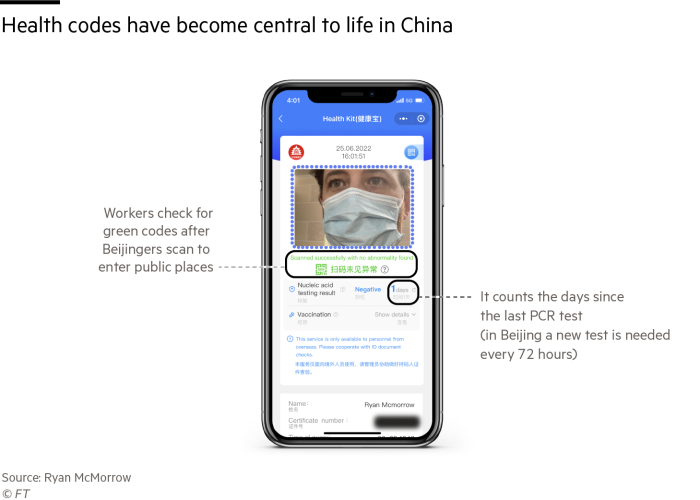

More than two years into the coronavirus pandemic, everyday life for most of China’s 1.4bn citizens hinges on the colour of a health code on a smartphone app.

Entering any establishment, taking the bus, strolling in a park and in some cities even returning home depends on the approval of health code applications that are central to the battle against Covid-19, but which have already been used by some officials as a tool of social control.

Beijing resident Guo Rui recently discovered the extent of the data that feeds into the health code system — which combines mobile phone location tracking and government-issued ID numbers with Covid test results, vaccination status and other personal information.

Just buying cold medicine, which now requires registration with an ID card, changed Guo’s health code status. When she next scanned a QR code to enter a public place, her phone displayed a pop-up message instructing her to get tested. “An alarm started beeping from my phone,” she said. “Everyone around me immediately backed away.”

The pop-up meant Guo was barred from entering any public venue until the new test was processed and the data fed into her health code app. People whose codes turn red must quarantine at home or in an official facility.

Zhengzhou, the capital of central Henan province, this month offered a demonstration of the dangers of such digital controls. City officials changed the codes of more than a thousand people to red to prevent them from protesting against the potential loss of their savings in local rural banks that are on the brink of collapse.

“They gave me a red health code and claimed that I’m a traveller from abroad,” said a 32-year-old Beijing resident and depositor surnamed Yang, who was prevented from going to Zhengzhou because of the change to his status in the Henan app that he would need to use while in the province.

China’s first health code apps were developed by tech giants Alibaba and Tencent at the start of the pandemic as simple contact-reporting tools similar to those built by Google, Apple and other software companies for use in many other nations.

But as President Xi Jinping has doubled down on his strict zero-Covid policy aimed at eliminating transmission of the virus, the patchwork of health code apps across the country and the systems that support them have rapidly increased in reach and sophistication.

They now allow health authorities to swiftly control the movement of thousands of people to crack down on outbreaks. A district in Beijing that detected three Covid-19 cases on Thursday, for example, needed just hours to put 9,785 contacts into home quarantine and ban another 77,388 people from entering public places until they had completed two Covid tests over a three-day period.

The Chinese government insists the system is purely for health purposes. In Zhengzhou, the local Communist party anti-corruption body on Wednesday punished five city officials for changing codes “without authorisation”.

“It is absolutely forbidden to change people’s health codes for any reason other than epidemic prevention and control,” Lei Zhenglong, deputy director of the National Health Commission’s disease prevention bureau, warned on Friday.

But the health code system is developing alongside a broad panoply of technologies pushed by Xi to ensure order. Digital social security cards, digital money, surveillance cameras and social credit systems are creating a grand experiment for 21st century authoritarian governance.

Maya Wang at US-based campaign group Human Rights Watch said Covid codes “allow authorities to control the population in the name of public health”, citing the lack of transparency around how they operate as a major concern.

“The health code is an expression and manifestation of the underlying philosophy of what the Chinese government calls new social management, which relies on the use of technology for social control and governance,” Wang said.

Escaping the code system is all but impossible. Commercial establishments that fail to check their customers’ status can be fined or shut down.

At the entrance to grocery stores or restaurants in Beijing, staff only allow in people whose codes show green and whose phones announce in an automated voice: “pass”.

Government procurement records in Alibaba’s eastern hometown of Hangzhou give a glimpse of the digital plumbing of the health code system that the company has helped build in the city.

This month, a joint venture between the ecommerce group and two state-owned firms won a 12-month contract to run the system, which is required to be robust enough to handle 25,000 information queries per second.

The records show Hangzhou’s 12mn residents are separated into several data sets, each with different rules. One data set for workers in the delivery and cold chain logistics sectors ensures they are given an orange health code for skipping a Covid-19 test. But a “white list” for pandemic workers and other “special groups” has instructions to protect them from getting orange or red codes while they are carrying out their duties.

Public worries about the health code system have grown since the revelations of its use in Henan to restrict the movements of 1,317 bank depositors.

“This is a new era of digital handcuffs,” said one. “Henan’s banks swallow depositors’ assets, [and the] Henan government gives depositors red codes.”

Zhengzhou authorities also appeared to have targeted a group of property buyers demanding action against a developer that is in financial trouble.

Melody Guo believes her red code was triggered by a visit to the local banking regulator to address the stalled construction of an apartment by property developer Sunac for which she paid Rmb2mn ($300,000).

“There was no official explanation about my red code at all,” Guo said. “I cried and cried in front of the neighbourhood committee workers, begging them to change my code and offer me a solution, but they said they couldn’t.”

On June 16, as reports of Zhengzhou’s misuse of the health codes flooded Chinese media, her code turned back to green.

Additional reporting by Nian Liu in Beijing

Comments