Just off the side of the expansive Sterling Medical Center rotunda is the Cushing Whitney Medical Library. Considering its world-renowned status, the translucent tiled sign above the door generates an unassuming, even cozy, atmosphere. After the main corridor of circulation desks, the path forks in two: on the right is the modern medical library, and the Medical History Library lies to the left. The medical library brims with textbooks spanning topics from surgery and immunology to rehabilitation and chemical reactions. The historical library (which is, in fact, just a single room) is lined with dark wood paneling and locked book cases, eerie silence and sculpted busts, giving it a mysterious importance. It is cold and intimidating, yet magically lit and archaically beautiful.

But more important than the decor of this old library are the books it houses. In wire cages that line the built-in shelves, the room holds the private historical medical book collection of three doctors, each with unique ties to Yale University. Well, a small part of their collection, anyway. No library could accommodate all 47,000 volumes in the collections, which range from textbooks to ancient artists’ renderings of the mysterious human brain.

Despite the value and intrigue of these books, many of which are printed via pre-Gutenberg Bible-era woodblock, they are not the source of the library’s true appeal. If you venture, as I did, through the shelves of medical resources, past sleep-deprived medical students and friendly librarians, down the quiet stairwell, you will come across the library’s real treasure. You slip through a glass door into a darkened room and soon dim, yellow lighting brightens the room, and you are surrounded by brains. Yes, you read that right. Century-old human brains preserved in crystal-clear glass jars.

The labeled glass jars line wooden, glass-cased shelves. And the way they are arranged in this dark room resembles, in the most eerie and endearing way, the books on their shelves just one floor above. Their arrangement and containment is careful and intentional and oddly comfortable. I navigated the shelves of brains just as I knew how to navigate a library. The brains looked man-made: their creases too perfect, their textures too smooth and dense. Some are sliced open, some diced, some whole: all preserved in an ominous dark liquid in sealed bottles, meticulously labeled.

And though it might seem like a purely scientific display, Coordinator of the Cushing Center Terry Dagradi describes it much more intimately: “This is about remembering the people whose lives were lost at this time.” I had goosebumps when I heard her say this; it made this striking room all the more moving.

So, you now know how I came to be in a room full of preserved human brains … but what are they doing here?

In short, they were left at Yale by the same man whose invaluable book collection comprises the majority of the Medical History Library. His name was Harvey Williams Cushing, class of 1891, and he is primarily responsible for not only the books and brain specimens housed in this Yale library, but also much of the foundation of the modern fields of neurosurgery, neuropathology and neuro-ophthalmology.

After graduating from Yale University in 1891, Cushing went off to Boston to study at Harvard Medical School. As part of a clinical shadowing program, young Cushing was responsible for administering the anesthesia during a major neurology procedure at the hospital. The patient died on the operating table, which was far from uncommon at the time — but Cushing felt guilty, confused and fascinated by the hospital’s failure to keep medical records and surprisingly unrefined surgical techniques. Cushing immediately began looking for technologies and mechanisms by which to standardize, and therefore improve, surgical anesthesia. He helped make the use of an record standard practice in Harvard’s operating rooms, but the introduction of the blood pressure cuff, among other medical innovations, was rejected by Harvard’s medical program for being too technical.

After receiving his medical degree, Cushing traveled south from Boston to Baltimore, where he landed at Johns Hopkins University as a medical resident studying neuroscience under William Stewart Halsted, class of 1874. There, he developed tools to improve the efficiency and safety of the then-primitive discipline of neurosurgery. He inched closer to some semblance of an answer to his primary question: how could he identify, locate, classify, and remove brain tumors? Without medical history, diagrams, or mentors on the subject, Cushing turned to the well-understood physical examination methods. He observed dysfunctions in manual dexterity and eyesight as indicators of obtrusive brain tumors. He pioneered the field of neuro-ophthalmology as a means of both diagnosis and classification. His innovations drew not on standard medical knowledge but on his daily observations. Once, Cushing attended the Ringling Brothers Circus, and was stunned by the circus giants. After diagnosing their condition as an over-secretion of hormones from the pituitary gland, Cushing threw himself into examining the pituitary gland and the effects of pituitary gland tumors.

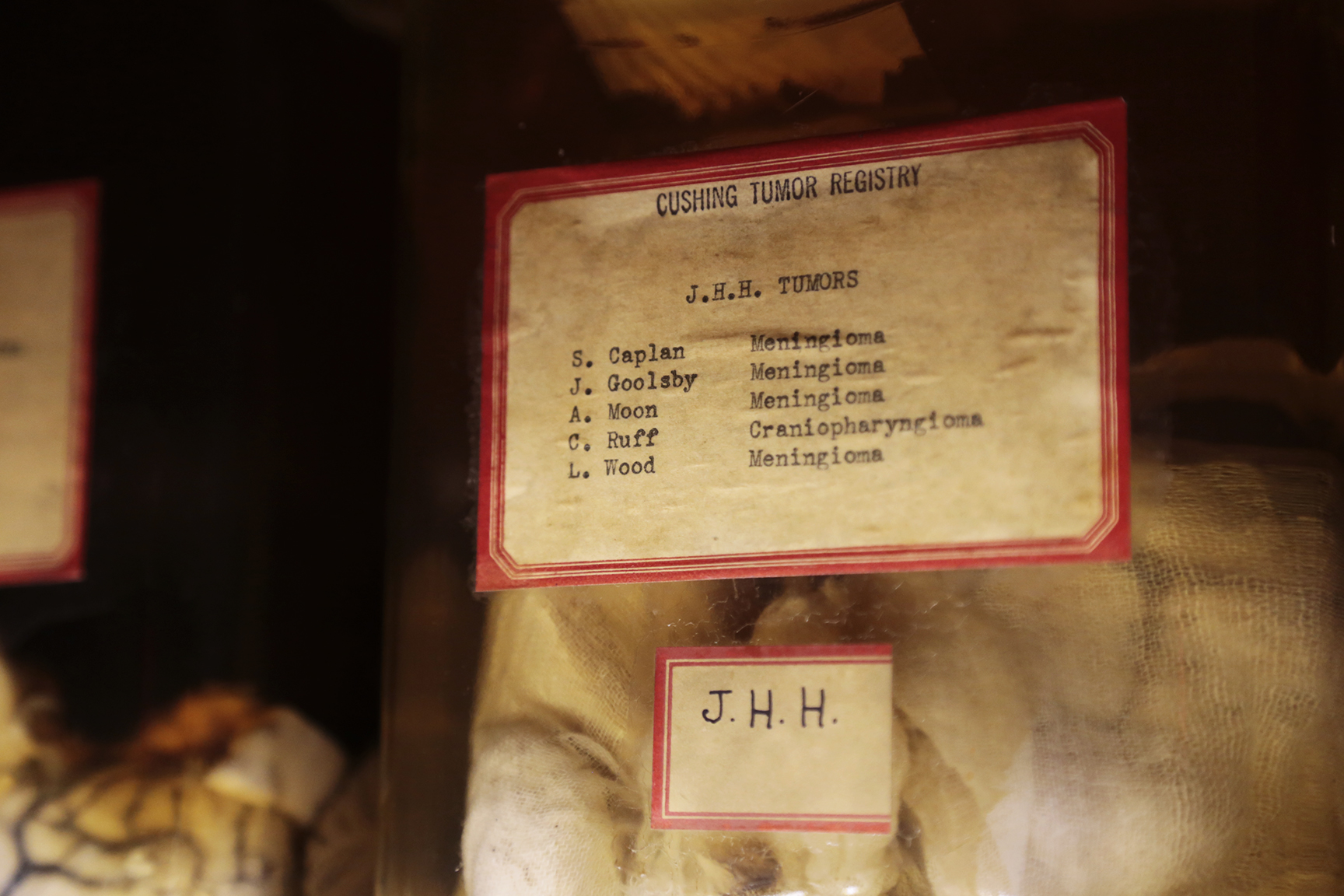

And it was through this method of physical diagnosis that Cushing was able to perform the brain tumor removal. When Leonard Wood, a physician and military strategist to President William Howard Taft, class of 1878, began experiencing frequent seizures in his left hand, he traveled across the northeast United States and to London seeking treatment. Finally, he was sent to Cushing, known at the time for being the leading mind of neurosurgery, to be examined for a brain tumor. And that was exactly what Cushing found: a benign fibrous tumor, which would later be called a meningioma. Cushing removed the mass, which heralded the beginning of his reign as the leading expert in brain tumor removal.

Wood’s brain is one of the 500 in the Cushing Center. Though his initial surgery was successful, the tumor was recurrent. He died on Cushing’s operating table decades later, and Cushing preserved his brain and the tumor before sending his body to be buried at Arlington Cemetery in Virginia.

It should be noted that these people whose brains are housed in the Cushing Center did agree to this public preservation of their most complex organ. They signed a contract with their obsessive doctor, but only for their brain. These patients did not “donate their body to science,” as we might say today: after the removal, the corpses were taken by loved ones to family cemeteries and hometowns, and buried in caskets rather than laboratory chemicals.

It must be mentioned that Cushing was unbelievably neurotic, no pun intended. He was meticulous and specific. He wrote 1,000 words a day about his agenda, progress and dissatisfactions, among other things. Additionally, Cushing was a wonderful medical artist; he received medical illustration instruction at Johns Hopkins. Hence, not only did Cushing provide a comprehensive compilation of written medical records, which corresponds to photos and jarred brains, but there remain beautifully drawn sketches of specific cases and patients in his many notebooks, which also reside at the Cushing Center.

But it was not just Cushing’s persistence, education or copious note-taking that led to his medical breakthroughs. Rather, he, like all of us, was a product of his circumstances. Becoming a practicing doctor just four years after the introduction of X-rays into diagnostic medicine, three years after the blood pressure cuff was pioneered and as cortical electric stimulation was being developed allowed Cushing to harness new technology to push medicine forward in a way his predecessors simply could not.

Though these technological breakthroughs occurred in disparate fields, Cushing’s multidisciplinary expertise allowed him to investigate as the technologies broke new ground. He could study hypertension and circulation in his own clinic; analyze radiographs of brain tumors himself; and examine electrically stimulated motor skills and sensory patterns in patients with severe tumors that he was learning to remove.

The way Cushing altered the modern concepts of neurosurgery might seem to us, in our age of 3-D printed organ transplants, laparoscopic procedures and prosthetic limbs, to be simple common sense. Yet, in the earliest days of the twentieth century, as Cushing traveled from New Haven to Boston to Baltimore and back again, his proposals were more commonly deemed innovative, efficient and monumental. With a fascination with blood pressure and its then-unknown connections and consequences, Cushing worked to understand, specifically, the relationship between blood and intracranial pressure, classification of brain tumors, and the fundamental connections between the fine motor skills of the hands and eyes to the placement and severity of brain tumors.

Cushing, however, did not do it alone. Louise Eisenhardt, the first female neuropathologist, was instrumental in both Cushing’s work and the preservation of his legacy. Starting as his editorial assistant, Eisenhardt was sent to medical school at Tufts University in order to be of more help to Cushing. So, when Cushing exploded in a fit of rage after the Johns Hopkins Medical Center misplaced one of his extracted tumors, Eisenhardt had the formal training to organize a personal, centralized bank of brains and brain tumors from both surviving patients and corpses. Her decision to centralize Cushing’s collection is what established the collection of brains housed on our very campus. Not only could Cushing impose his obsessiveness and organization on this collection of biological resources, but it also provided the opportunity to learn from surgical mistakes and misdiagnoses.

After being drafted to serve in army hospitals during World War I, where he used magnets to dislodge shrapnel from the brains of soldiers, Cushing’s health rapidly deteriorated, so much so that he was forced into retirement at age 63. Universities competed to lure Cushing (and his significant library) to their campuses, but the familiarity of his alma mater and the promise of an endowed chair were enough to attract Cushing back to Yale. Cushing and Eisenhardt journeyed to New Haven with books and brains in tow. There was an understanding that a historical medical library would be commissioned to house the abundant volumes, which now included both Cushing’s personal collection, as well as those of John Fulton, the chair of physiology at Yale, and Arnold Klebs, a tuberculosis specialist at Johns Hopkins. The brains, though, had no explicit destination.

Harvey Cushing died in 1939, just before the library’s construction was completed.

Without Cushing, Eisenhardt assumed control of the collection of brains. As aspiring neurosurgeons studied for their exams, these brain specimens proved to be enormously valuable resources. Yet as the decades went by, fewer budding surgeons were familiar with Cushing’s monumental collection, and with Eisenhardt’s retirement in the 1960s, the brains became more burden than benefit.

Quite possibly because disposing of them would have been an ordeal, the brains were put, out of sight and out of mind, into the basement of the Harkness medical dormitory. And it was there that Christopher Wahl MED ’96 and his fellow medical students found the trove of brains almost 30 years later, in 1989.

“Did you know that the medical students break into the Cushing room in the subbasement every year, and they commune with the brains and then sign a poster and then leave?” Wahl asked Dr. Dennis Dee Spencer, the chair of Yale’s Department of Neurosurgery. Spencer was unaware of this medical student rite of passage, so he agreed to venture with Wahl to the sparsely lit basement. Flashlights in hand, he found more than he had expected.

“It was the classic single lightbulb hanging from the ceiling, the stalactites on the walls, a disgusting smell and lots of dead creatures on the ground,” says Dagradi. And although Spencer knew the brains were there, buried and hidden in that dusty subbasement, he was astonished to find Cushing’s 10,000 glass plate photographs tucked behind the brain-filled shelves. Spencer notes that this, not the brains in jars that seem so striking to most visitors, was his “major discovery.”

“[The photos] are beyond. It’s beyond a clinical photograph, as we know it today. Patient information and privacy was not as carefully guarded, so, whereas today, if you were photographing a scar on someone’s body, you would probably go much closer in, you would de-identify the patient as much as possible. But with these portraits, if you know the person, you’d know the person. It’s full faces, it’s full nudity, it’s scars and smiles, along with the terror in people’s’ eyes when they realize that they may have something that’s about to kill them. So, it’s a much more powerful image,” explains Dagradi.

And when you visit the Cushing Center, and I hope that you do, you will be jarred and moved by these photographs. I know that I was.

There are pictures, as Dagradi described, of toddlers with bulging tumors, lying, bedridden in hospital gowns. There are pictures of giant men in excruciating pain, covered in scars. There are pictures of mothers and fathers and their children, hand held over heart, suffering unimaginably, posing for Cushing’s lens all the same.

Wahl was persistent, and completely fascinated with this underground collection. After committing his final year at Yale School of Medicine to a thesis on Cushing’s work and legacy, he and Spencer, and eventually Dagradi, rummaged through empty library floors and old gallery spaces, looking for a place to present the collection and the money to do so.

The 21 years between Wahl’s rediscovery and the opening of the Cushing Center I visited just a few days ago were spent searching for the space, the architect and, most importantly, the money to fund such an ambitious endeavor. In the course of his extensive research, Wahl unearthed vague mentions of the Hanna Fund, created in 1939 in memory of a child who had been treated by Cushing and died of a pediatric tumor. Spencer’s term as interim medical school director allowed him to locate the modern whereabouts of this fund, which held $1 million — enough to fund the creation of an exhibition space for the Cushing collection.

Turner Brooks ’65, adjunct professor of architecture at Yale, was chosen to design a space for this unique exhibition. “He’s both a magician and a poet, a visual poet, so he came up with this beautiful design for the center,” says Dagradi. As Brooks explored campus basements and vacated spaces, Spencer and one of his graduate students extracted the brains from their rusty jars, disposed of the ancient formalin, reautopsied the specimens, and resealed the sacred brains.

The brains were ready, the space was nearly ready, Spencer and Wahl and Dagradi were certainly ready. As the collection took up residence in its new space, Brooks’ architectural brilliance — as well as the sheer magnitude and glory of Cushing’s brain bank — became obvious. The wood in the building is cut from a single tree, giving the shelves and cases beautifully uninterrupted seams. The lights glow dim so that the brains become lanterns. The photographs prominently line the entirety of the exhibit.

Rescued from the dorm basement to which it was once consigned, Cushing’s magnificent collection of brains, photographs and notes is not only an incredible historical snapshot and a creepy delight, but also a valuable scientific resource that is still yielding new discoveries almost a century after the death of its founder.

It was on a scavenger hunt as part of her Yale School of Medicine 10th reunion four years ago that Maya Lodish MED ’03 found herself in the Cushing Center. Stunned that her university housed the collection of the doctor for whom the disease she studies, Cushing’s syndrome, is named, Lodish began to conceive of ways that modern genetics could take advantage of the magnitude of Cushing’s relatively primitive collection.

Lodish’s discovered a new gene directly associated with acromegaly, the same “circus giant” syndrome that Cushing had naively identified so many years prior, and wondered if her gene was present in the preserved, century-old brains. Again, the brains were put to use beyond display. “Cushing’s meticulous records allowed us to pool the acromegalic patients’ brains, sample tissue from those specimens, take them down to the NIH, and deem that the gene was conserved,” says Spencer. “This project explored the collection’s remaining research implications, despite passing time.”

Contact Shayna Elliot at shayna.elliot@yale.edu .