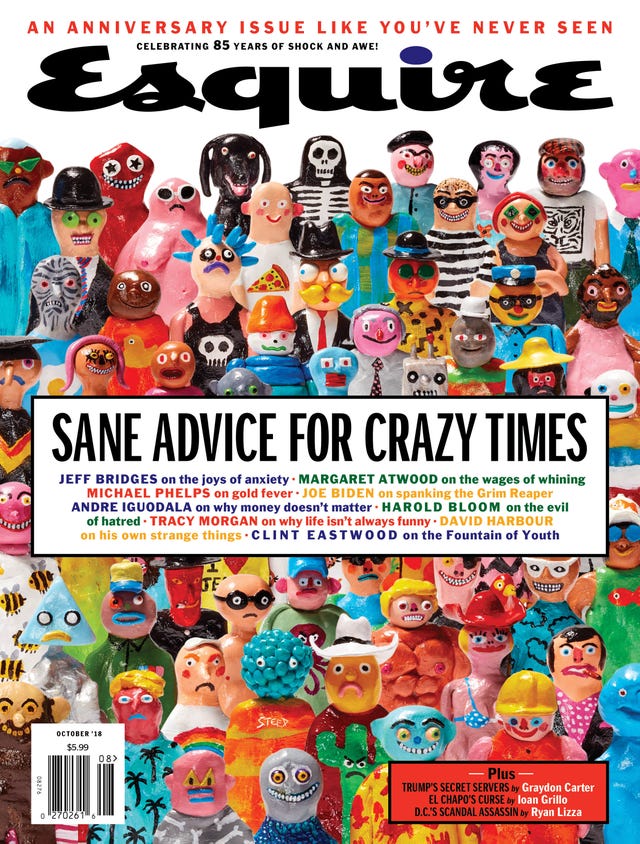

You probably noticed that our cover doesn't look like the other ones on newsstands this month. For our 85th anniversary issue, our design director, Raul Aguila, and our cartoon and humor editor, Bob Mankoff, asked the cover artist, Ed Steed, to imagine one that brought to life this issue's theme: "Sane Advice for Crazy Times." Steed, a British cartoonist who has previously contributed to Esquire, spent three weeks sculpting 85 clay figurines. There's the somber graduate, the robot, the punk rocker—all just as hard to categorize as our difficult, breakneck-pace moment in time. "I miss 'em," he says. "Every day I woke up and saw these little faces look back."

You’ve said, “Through purpose, you can find your way through grief.” How can someone identify his or her purpose when it may not seem clear, especially in a time of confusion and immense pain?

I have kept a strip from the cartoon "Hagar the Horrible” on my desk for a while now. It is the kind that you can find when you walk into a greeting card store, enclosed in a little glass case. My father bought it for me and gave it to me one day when he came over to the house and I must have been feeling a little down or sorry for myself. In the cartoon, Hagar—the Viking captain—and his ship were struck by lightning. The ship is sinking, and he's standing on the shoals asking, “Why me God?” And the next frame is the same picture, and a voice from heaven comes out and says, “Why not?”

For me it has always been a reminder that there are a lot of people are going through a lot worse than what I’ve gone through. The way they get through it is that they have people reach out, embrace them, give them solace. By being open to that solace, you can find a purpose. If you have a purpose, if you have a responsibility, sometimes it allows you to just keep pushing through. It is the thing that gets you up and gets you focused, not on yourself or not just on the part of your soul that is missing, but on moving forward.

That was why I wrote Promise Me, Dad. I wanted people going through a loss to have the belief that they could get through it. Having purpose allows you to look to the future, and not focus only on what you’ve lost.

You’ve talked about how the phrase “I know how you feel” isn’t always the best medicine, but often people feel unsure of what to say to someone who’s lost a loved one. What are the best ways to support someone who’s suffered a great loss?

In my family, we have always had a saying that, “If you have to ask for help, it is too late.” It means you are never alone. It meant that no one ever has to ask, because someone is always there for you.

After I lost my wife, Neilia, and our daughter, Naomi, in a car accident right after I was elected to the Senate, and both of my boys were barely injured, my sister Valerie and my brother Jimmy moved in with us. I never had to ask. They helped care for the boys and kept the family going.

Often the best way to support the people in our lives who are suffering from terrible loss is as simple as showing up.

Your mother said to you, “Out of everything terrible that happens to you, something good will come if you look hard enough for it.” How can someone deep in the abyss of grief get into the mindset of looking hard for the good things?

One of the best pieces of advice I received after I lost Neilia and Naomi came from a former Governor of New Jersey. He had also suddenly lost his wife, and his recommendation was a simple one: start to keep a calendar. And every night when you go to bed, mark in that calendar whether the day was a 1, which is as bad as the day you heard the news, or a 10, which is as good of a day as you could have. He said you won’t have 10s for a long time. But measure it. Just mark it down. He said after two months, take out that calendar and put it on a graph, and you’ll find that your down days are just as bad as the first day. Over time, those bad days get further and further apart. That’s when you know you’re going to make it.

Someday the thought of your loved one will bring a smile to your lips before it brings a tear to your eye. It might not come to you in an epiphany, but instead slowly over time. But you’ll get there.

Somewhat unrelated, but to add a note of lightness to this (plus we’re all dying to know!)—what do you do for fun? What makes you smile and put aside your woes when your heart is heavy?

You know I’ve been traveling a lot, first for a book tour, but then for the projects I have going on at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Delaware, and elsewhere. I enjoy working out and riding my bike, especially along some of the trails in southern Delaware. I’ve been reading a lot the last few months. But the thing I love most of all is being able to spend some time with my family. Bodysurfing or going for ice cream with my grandkids at the beach, going out for dinner with my wife, Jill. That is really what brings me joy. —interviewed by Adrienne Westenfeld

How do you cope with being afraid—on a mountain wall or anywhere else?

As we’ve been chatting, I’ve been walking down this trail, and before I left, this woman was like, “Do you have any bear spray?” and I was like, “No, it’s fine.” And as I was walking I stepped over two fresh piles of bear poop and there are tracks everywhere. And I’m like, “Oh, there are a bunch of bears here.” But that’s one of those things, like, if I got eaten by a bear, I’d be like, “Well I made a bad decision and I paid the consequences for it.” It reminds you how little your anxiety matters, because there’s this cold hard world out there that does not care about you.

People use “overcoming” or “conquering” fear as a way of managing fear. I view that as: I’m afraid of something but I’m just gonna suck it up and do it anyway even though I’m afraid. And that can get you so far—that can get you to step onto the dance floor. But that won’t get me to free-solo a big wall. I can’t just overcome it. Because the reality is it takes me hours and hours to climb the wall, and you just run out of that overcoming. So I think that the only real way to manage fear is to systematically broaden your comfort zone so that you’re not afraid of it anymore. You just have to basically desensitize yourself until it’s not scary anymore. I think that’s the only real way to deeply manage fear. There are tons of ways to trick yourself to do something even though you’re very afraid. But the sustainable solution is just to no longer be afraid. And that requires a lot of practice, a lot of time, a lot of desensitization.

Now that you’ve presumably desensitized yourself to fears about climbing, what’s something you’ve more recent been afraid of?

I did a TED Talk earlier this spring and I was pretty much mortified. I gave my tech rehearsal, which is in an auditorium that is mostly empty, and I fully froze even though I basically memorized my presentation. I was like, Well I have no idea what I’m doing. Because in a way it was even weirder to give a rehearsal talk when nobody was really paying attention. And then I sort of pulled it together and practiced a lot more, and when I gave the real talk, I still found it quite intimidating and in the end I totally blanked on one paragraph and skipped a section—and nobody noticed and it didn’t matter, and I think the talk went great. But it still wasn’t perfect, so I was like, I still have a long way to go in terms of overcoming that kind of fear.

The average person is probably most afraid of or most craves acceptance. So they’re most afraid of public ridicule, or being an outcast. But the thing is, fear should be related to danger. So most of the fear I’m dealing with climbing is a legitimate If I mess this up, I’m going to die, and that’s a very appropriate fear to have. That’s something that I would never want to do away with because it’s an important warning. So I think maybe the key thing is to differentiate between fear that serves you and fear that doesn’t. —Interview by Brandy Langmann

You’ve worked hard to bring clean water to your hometown in Brazil with the Agua Limpa Project. Is that a model for change? Should people focus their efforts locally?

I do believe in tackling issues at the local level is very effective. Communities know their individual needs. I believe that when communities work together they gain strength. Unified in finding solutions they can create positive environmental changes that will have an impact on their lives and the rest of world.

What about the future? How can we raise children to prioritize sustainability?

I believe education is key. If kids learn the importance of taking care of the Earth starting in school they will know how their choices will either help preserve the Earth or destroy it. Knowledge will help them to participate in creating a world they want to live in and leave for future generations.

You been quoted saying you were reading Lao Tzu and Thich Nhat Hanh as a teenager. Do you still find them meaningful?

I have always been fascinated about philosophy, ancient civilizations, and mysticism. The books that have had the biggest impact on me were Siddhartha; Bhagavad Gita; Many Lives, Many Masters; Transformation and Healing; and The 4 Agreements. —Interview by Adrienne Westenfeld.

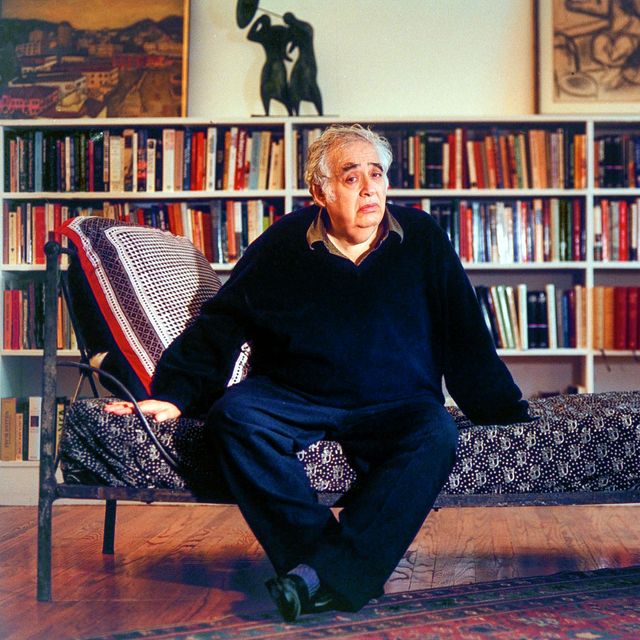

What does religion have to offer a person living in the 21st century?

That’s a question I’ve been asking myself. Why is religion still around? I just finished a book called Why Religion: A Personal Story. I was brought up in a family in which my father had given it all up for Darwin, who said religion is for uneducated people—nobody needs it. Much to my parents’ dismay, I got fascinated by it. But I don’t study religion abstractly. I explore religious traditions, and what they are are stories, songs, poems, which try to interpret the way people live. They articulate the ways that different cultures have tried to find meaning. And I think these religious traditions are very different. I mean, Judaism and Buddhism are very different. So are Christianity and Hinduism. So I think these traditions basically address the questions you’re asking with this article.

What has religion taught you, as a scholar and in your own life?

When a life-changing event happens to us, we instinctively ask ourselves, What does this mean? Is it good luck? Is it God’s will? Is it random? Is it because I did everything right? Is it because I did everything wrong? That is, we’re not just experiencing—we’re always interpreting. So how we interpret events matters enormously. And these religious traditions offer cues for the ways to interpret things. Do you go into fear, anger, isolation? Or, is it possible to deal with events in a creative and open kind of way that allows for becoming more alive and aware and creative? Those are the questions that are crucial in these traditions. I’m fascinated by these traditions because as I read them, they’re about what art and music and poetry and drama are about. In fact, most of these traditions consist of art, music, poetry, and stories. People can deal with those questions through any of those modes of experience, or through science, as I saw with my husband. So I’m not so much a believer as an explorer, as a seeker of these traditions.

Is faith necessary to receive the wisdom in religion?

I don’t think so at all. Faith is a particularly Christian preoccupation. Protestants talk about it more than Catholics do. If you talk to a Buddhist or to many Jews, it’s about practice; it’s about what you do. If you take something like the Torah—“You shall not kill, you shall not commit adultery, you shall honor your parents”—there are very specific ways of acting, and that’s what really matters. It’s about justice and mercy. Buddhism is about the practice of compassion and generosity; it’s about seeing reality the way it is and attempts to do that through meditation. It’s about how you act, what choices you make.

Is the kind of interpretation you’re talking about strictly a personal matter, or is it best accomplished through a community or tradition.

People say “Are you a religious scholar” and I say “Well, I’m a scholar of religion.” I’m sort of incorrigibly religious because I’m captivated by this kind of imagination. But if for example you grew up in Jewish or Christian tradition, there’s all kinds of attitude about sexuality, about ethnicity, about social and political structure, that are built into those traditions. My family was nominally Protestant, but not religious at all, and still I was shaped a lot by attitudes in those traditions. And that doesn’t mean I embraced them; it means I’m curious about them. Some of them I reject because they don’t work for me in the 21st century and they have to be discarded. Others may still be very useful. And some people as you know go to completely different cultural traditions and find those to articulate a sense of meaning better than whatever they grew up with.

Do you think the truth and wisdom in religion are going to remain relevant for the challenges of the future?

That’s a good question. They may become completely outdated. For example, the idea in Genesis that humans were given the earth to dominate and subdue, that’s not working too well these days, right? Some of the native American traditions would say we are part of this earth, the earth is our mother, it gives us life—we’re not above it, dominating it. The study of religion gives you perspective. You don’t have to just say, “Oh it’s deep wisdom, we have to follow it.” Some of it is not. My Evangelical critics call me Elaine Pagan because they think anyone who teaches the history of religion is supposed to swallow the whole thing, but I think it’s indigestible.

Because we live in the 21st century, we can’t be unaware of the tremendous diversity of cultures. I guess some people are comfortable staying within whatever was good enough for Moses, but for a lot of us that doesn’t work. I also don’t think religious traditions are the only way to find questions of meaning.

—Interview by Ash Carter

You clearly love to talk to people—to the point that you’ve made a professional life out of it. Is there something you’re getting out of conversation on a deeper level?

I am a recovery guy, and the premise of AA is really you talk to somebody else and it helps both of you, because you’re not thinking about you. [When I started the podcast] I had sort of drifted. I’d gotten cynical and bitter and I was alienated from a lot of my peers and from comedy. So to call on people I knew from comedy for years to be the guys I talked to, it showed two purposes. I was getting these great interviews, or whatever they are, and I was also reintegrating myself into my community, and hearing about the lives of other people who’ve dealt with similar things to me. It definitely served a personal growth purpose for me. But I’ve always enjoyed talking to people that have stories, that have charisma, that are funny. I’ve always liked that my whole life, because my father was so inattentive in a lot of ways and I just kind of wandered the world talking to charismatic dudes who had some sort of guidance for me. I think the style of conversations that I have on the podcast sort of grew out of that—an emotional need as opposed to any sort of design.

Also, by the time I started the podcast I was kind of close to broke. I was in a bad place and I was looking down the barrel at a life of quiet, probably not so quiet desperation, of playing B-comedy rooms for maybe a few people that knew me. But as time went on the podcast evolved into what it was, and it started to have an impact culturally, my cosmic timing was good for once. It was before podcasts blew up and I kind of helped define the medium, and my business partner, Brendan McDonald, and I just did our work, and I evolved and the show evolved and the business evolved, and all of the sudden we were sitting on a business—me and Brendan who aren’t business guys.

The point being we were able to do everything on our own terms. Obviously that’s not advice, because what are you going to do, just tell somebody, “Hey, just do what you really want to do and it’ll work out and you’re going to feel better.” I mean, look, there there is an element of timing here that is completely out of my hands, and I’m very grateful for that, but that’s the truth. —Interview by Alex Belth

A couple of years ago, I had the privilege—for the second time in my career—of spending time with Clint Eastwood. As I’ve written in the past, I think he’s always been an inspiration for anyone who hopes they are a late-bloomer. Because for all his accolades and accomplishments, it’s worth remembering how late “success” came to him: he did not direct his first film until he was forty (Play Misty For Me); he didn’t win his first Oscar until he was sixty-five (Unforgiven). And from that first Oscar until now, he’s won four and been nominated for eleven. Now, at age eighty-eight, he’s in the midst of directing his thirty-seventh movie, The Mule.

So, as I sat there in his bungalow on the Warner Bros. lot, the late-afternoon sun glowing warm in the windows, and Eastwood seated on the couch across from me, his long legs stretched out on the coffee table between us, I wanted to know how he maintained his vitality, professionally and physically.

Eastwood looked at me and grinned and said, “Every so often, you’re gonna hear a tap-tap-tap. Whatever you do, do not let the old man in.”

—Michael Hainey

What is the upside of passion?

The upside of passion is that it can get you through the shittiness. It gets you where you want to go—to your goal.

What might be the downside?

Passion can be rocket fuel. The problem is when you have that singular focus, what happens when you get to the goal? All the books you read are about getting to the fucking mountaintop. No one ever, ever, ever wants to talk about how to come down from it.

Your success, early on, seemed to have been fueled in part by rage. Is that still true?

So much of what I was trying to do was because of my anger at my place in the world, or being slighted, or whatever. It works when you’re young. It just doesn’t work anymore. That’s where I’m at. I’m turning 41 now—it’s been like a five-to-six-year process of my trying to find a different source of energy.

Just because you know it doesn’t mean you can. It’s hard, man. I’m really good at being angry, man. And really good at being rageful. Because it was defense and it was fuel. The problem is that at some point it begins to define everything you are. And I as a person want to grow. The problem is, where I’m at, if you let go of the past—I mean, I’m personally afraid of what the future might hold if I don’t have that anymore.

You’ve continued taking risks in the food world. Why?

Almost every decision to me I liken to a grade-school dance and being a wallflower. You have to ask a person out for a dance or a date, and you risk humiliation and failure. And if you do fail, is that such a big deal? Considering the circumstances when you’re in that moment, you may think it’s the biggest decision of your life, but in reality nothing really matters. The only thing that really, truly matters is that you’re born and then you die.

How has your view of cooking changed, over the years, in terms of what you want to give people?

I think it’s a daily battle to try to remove your ego from something. Do you want to feed people, or do you want to impress people? When you slice a duck breast so it looks pretty on a plate so you can win an award—that, to me, is relatively stupid. Why not just serve the fucking duck breast uncut?

— Interviewed by Jeff Gordinier

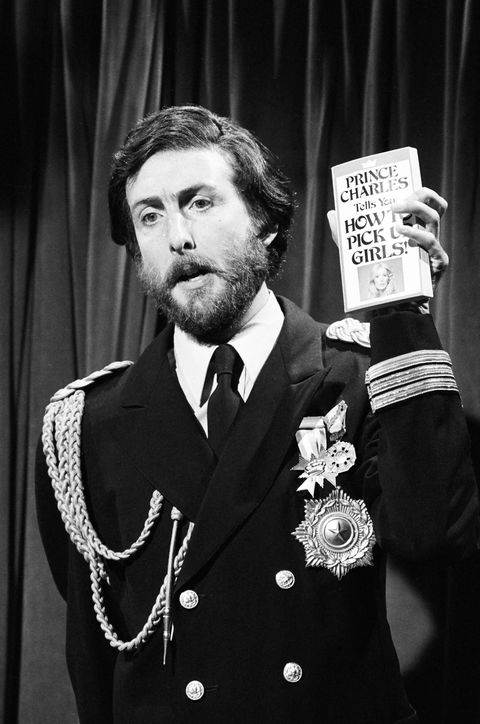

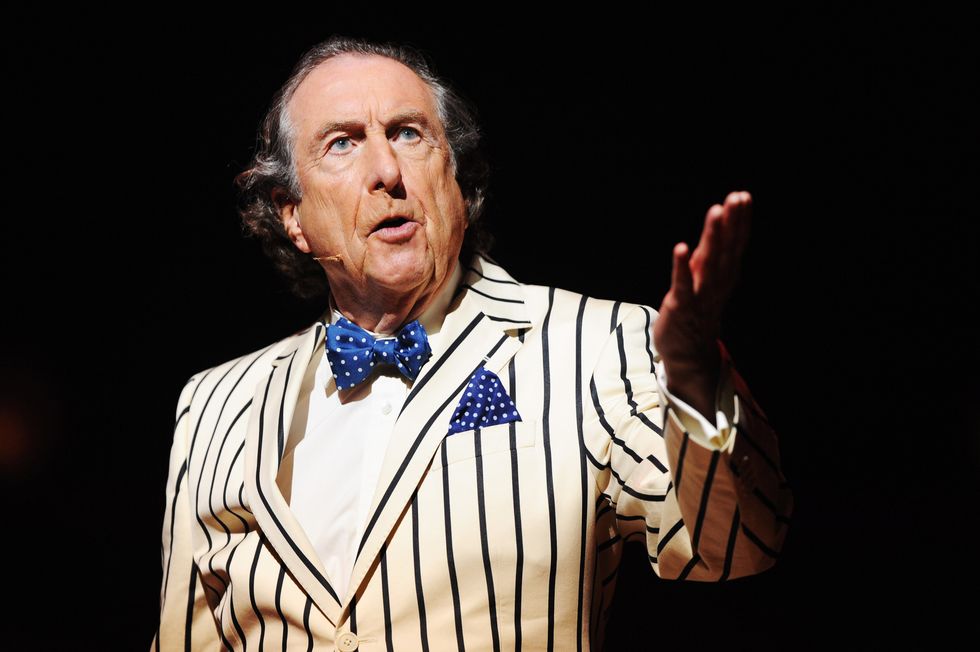

In your “sortabiography” you write candidly about how callous you were as a young man, especially with the women in your life.

I was not callous, not deliberately so anyway; I was ignorant and unthinking. Nobody teaches you how to be: there is no manual. I came out of a harsh environment where kindness and empathy was rare, so I had to learn these essentials. Of course we are all pre-occupied with our “selves,” we only have our selves, but as we grow up we became aware of others, and, hopefully, learn to treasure them, love them, and value them.

Inspiration or perspiration?

Hard work is the only recipe for success. My Cambridge comedy club, The Footlights, had a motto: Ars est Celare artem, the art is in concealing the art—whilst the RAF motto was Per ardua ad astrem: through hard work to the stars. I think of writing as like fishing: if you’re not at the river bank first thing in the morning you’re not going to catch a fish. What size of fish you haul out is a different matter. The river of the unconscious is a wonderful and devious companion.

You appear in the recent HBO documentary on Robin Williams, who was a friend of yours. He’s portrayed as hungry for attention and validation from strangers. Is that something you—or any comedian—can relate to?

Robin would always have to entertain other people. Even quietly having dinner in Paris alone with me he would get up and make the next table laugh. Sure, it was Lionel Richie, but he needed the attention of strangers. It was insecurity of course, but for him an important affirmation that he was still funny. When he lost that ability, he lost everything.

All comedians crave love and support from strangers. It is not a normal thing to do to stand on a stage and seek laughter and affection from a crowd of people you don’t know. So, all comedians are to some extent screwed up. The funniest, often the most so. Someone rudely called comedians “laugh junkies” and it is indeed a need. They want that fix, that reassurance that comes from making an audience bark.

Many successful performers talk about feeling undeserving, as if someone is going to tap them on the shoulder and say, “Welp, you’ve had a nice run, but we’re going to take this all away.” Do you struggle with that, or are you proud and satisfied with your career?

Well we know for certain that Death taps you on the shoulder and takes everything away, so don’t count on anything. George Harrison constantly reminded me that even the very rich and most successful have to die, so don’t base your life on those two false gods. Everything will be taken away. I offered to take some of his away to ease the burden for him, and he laughed very hard… but he was right.

I do feel immensely blessed in my life. Though raised in loss and sadness, I grew to find friendship and then love, and then the joys of family. I have had a great life. When I was born Hitler was trying to kill me and now my name is on Mars [as part of a list of visitors to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab which was placed inside the Curiosity rover]. That’s kinda amazing in one lifetime. And of course, I know they will be singing “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” at my funeral. —Interviewed by Alex Bleth

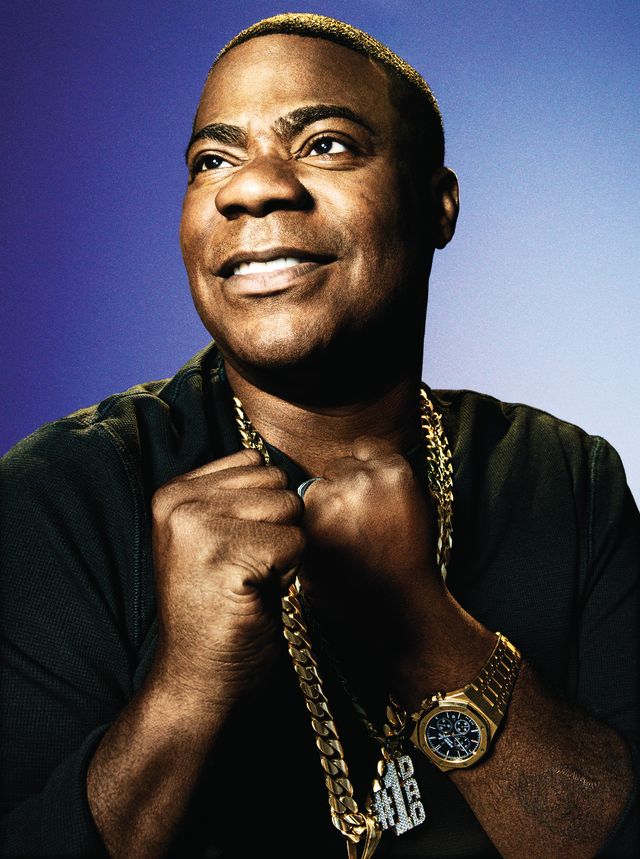

You had a long recovery, more than a year, following your auto accident in 2014. Where did you find the inner strength to cope with that?

[Sings.] The sun’ll come out tomorrow…. Tomorrow! I love you! Tomorrow! [Laughs.] You gotta sing the Little Orphan Annie. The sun will come out tomorrow, man. You don’t gotta care about Trump. You don’t gotta be shot. You don’t gotta be strangled. You gotta wake up.

I grew up knowing second chances. From my dad. He survived Vietnam—people died all around him. He came home. He explained to me what a second chance was. Love everybody—that’s all he used to teach me. The hardest part about my accident was forgiving the driver and moving forward. It was about loving everybody. Forgive those who trespass upon you. I could’ve been a really bitter person. But if I didn’t forgive, I wouldn’t have been able to move forward. It was for me to move forward with my life.

What about confronting and forgiving your own mistakes? You’ve made some statements over the years you’ve regretted and later apologized for.

We all make mistakes. Don’t beat yourself up. But if you must beat yourself up, don’t use a bat, be gentle, you’ll hurt yourself with that bat. Lorne Michaels told me that one day. I felt really bad on SNL and I was beating myself up, and he started laughing. He grabbed me by my shoulders and said that. And that’s why I love Lorne Michaels like I love my daddy—because he let people do that, and I want to pass that onto others. Don’t beat yourself up, we all make mistakes. You’re only human.

There’s only one way out of the darkness, whatever darkness that you’re in—to put yourself in the service of others. You’ll be too busy helping others to think of the dumb stuff that you were doing. I mean, if you’re in you’re in your neighborhood, in your community, find a hospital, and then go to the children’s ward. Just go to the hospital and help out. They may need another hand with some boxes for the patients. You’ll be a better person. If you do those types of things, like service to others, you feel like a different person. You’ll never feel the same again. This is what Angelo Dundee told Muhammad Ali many years ago. I live by these words. It doesn’t cost anything to be nice. —Interview by Brady Langmann

You must have experienced a lot of anger over the years, especially when your successful suit against Goodyear was overturned on a technicality by the Supreme Court, in 2007. What have you learned about how to manage anger?

My mother taught me not to get angry, because you lose your momentum and your focus if you get angry about something. One psychiatrist who interviewed me for his book kept telling me how mad I was, and I said “No, sir. Disappointed, humiliated, yes. Mad, no.” I couldn’t let it get me down because I had to keep persevering to get through. You always have to have hope. If a person files a charge such as I did, you have to be a strong individual and have a tough skin. You need to have a family behind you that supports you. And you need a strong faith.

Those are the three things that saw me through. There were times I didn’t know which way it would go, but I would never give up because I told my family when I went into this, “I am not backing down.” Whatever it takes, I’m going all the way. But I will tell you—I can’t stress it enough and I know people can’t understand it—I’ve never been bitter. All I’ve been is devastated and humiliated.

People often say, “I’m just one person—how can I change anything?” What advice do you have for people who feel that sense of defeatism or smallness?

Whatever it is you need to change, you need to have a good sales pitch and continue selling. You can’t change people—I learned that through getting married—but you can give them your sales pitch. And I am a positive believer. —Interview by Adrienne Westenfeld

When I graduated from high school, a classmate’s father gave a commencement address that offered a formula for living a meaningful life. His message still rings in my ears. Sitting there that warm spring evening, I thought I had my life plan all figured out. But then the speaker posed three simple questions:

“What will be your life’s work, and how will it make the world a better place?”

Well, I was sure that I was set on that one–go to college and study chemistry! But then I learned there was a lot more to think about. The speaker emphasized that the true measure of professional success is not academic honors or financial rewards, but how your time and talents are used to help others in a hurting world. Hmmm. Eventually, that kind of thinking led me to medical school, medical research, and a deep interest in global health.

“What role will love play in your life?”

By love, the speaker meant not only romantic love, but also the more universal and selfless love, called agape, that seeks nothing in return. It’s the kind of love portrayed in Steven Spielberg’s powerful movie Schindler’s List, in which a German businessman risks his life and money to save hundreds of Jews he doesn’t even know from the Holocaust. Like most teenagers, I was totally in favor of romantic love, having recently found a girlfriend who actually seemed to enjoy my nerdy company. But investing in this other kind of selfless love? That was less familiar to me.

“What place will faith take in your life’s journey?”

The speaker concluded by asking us whether we would explore and develop the spiritual part of our identity throughout our lives, or wait for illness or advancing age to force a crash course. I must confess that question made me cringe. While I’d sung in a church choir and found it a great way to learn music, I regarded the concept of God as outmoded. Instead, I had decided to anchor my faith in science. It took another 10 years before I realized what an impoverished view that was. Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that this is the most important life question of all.

So, when is the last time you’ve taken stock of your life in these three areas? If you’re looking for some help in building a more meaningful life, this would be a great place to start.

You’d been a starter since your rookie season, but in 2014 you were asked to be a back-up. You not only accepted that without complaint, you helped lead the Warriors to the first of three championships that season and won the finals MVP award. How did you come to terms with that new role?

Well, Steve Kerr came in [as the team’s new coach]. Training camp went well for me. I felt really good, like at the peak of my game as far as having an understanding for the game matched with my athleticism. It was my second year with the team so I was accustomed to playing with Steph [Curry] and Klay [Thompson]. Coach pulls me to the side—and I know it’s not a normal conversation. He says, “You earned a starting spot. I feel like you really earned it. ” And I know, just having a sense of people, I knew something was up. After that—we don’t usually have that kind of conversation—he was like, “You know, I think it’s best for the team if you come off the bench.”

But the interesting thing is, we went to the same college [Arizona] and we were coached by the same college coach [Lute Olson]. We have the same basketball philosophies, kind of the same understanding of the game. So I understood what he was trying to accomplish, and that made it much easier. I think that gets overlooked. If it was another coach, I don’t know how it would’ve went. It was kind of the first time in my career where I had to sacrifice just me going out and playing and doing what I do. Less is more type of thing. I bought into it, but it was hard to adjust to.

The social media world that we’re in now, everything is under a microscope. Your most recent performances are forgotten very fast, and it’s like, “What are you gonna do next?” So it’s hard for a lot of our younger players to really buy into sacrificing or doing what’s best for the whole without getting attention for it. But as you get older and mature, you see it has to happen in order for the team to succeed. Things will come back 360 for you. That’s pretty much the case that season.

It may not be as fast as you want it to be, but it’ll come. And it’s just kind of characteristics of a good person: humbling yourself, really having respect for whatever it is you’re doing—you’re not doing it for the money. I mean, obviously we’re doing it to make a living, but if you have a true passion and true joy for what you’re doing, it’ll always come back full circle for you. —Interview by Brady Langmann

No, I'm not an oracle! No one can predict “the Future,” as there is not one future. There is an infinite number of possible futures, and too many unpredictable factors to guarantee only one. But I do look at trends and past human behavior, and stories can be built on both. I’m not a sage, either. I'm quite curious about things, however, and continue my childhood habit of looking under rocks. Sometimes there are only worms. Sometimes scorpions. Sometimes genies in bottles. Sageiness can develop from such experiences.

So can hope.

Hope is part of the human tool kit. We need it to go on in the face of negative odds. I’m probably an inherently hopeful person. If I weren't, why would I write? Think how much hope is involved! You hope your book will be good. You hope you will finish it. You hope it will be published. You hope the perfect reader will come across it, and find all the breadcrumbs you've dropped in the forest, and also find some meaning or delight in them. That's a lot of hope.

I don’t despair easily. I guess I'm from a different generation. I grew up sitting in the bottoms of canoes, in rainstorms. It was the War. Spam was a luxury. Whining was frowned on. But, yes, I get tired and will probably get more tired before I'm done, but I'm not there yet.

My families were from Nova Scotia, and family loyalty is a strong value there. My immediate and extended families remain central to my life, but I have always tried to keep that separate from my public presence, as much as is possible. As you get older your priorities change. I am approaching the moment in The Godfather where Marlon Brando falls over in the tomato patch, and that focuses the mind.

The only way out of the current political and social climate is through. It’s roll-up-your-sleeves time. All human beings are human and should be treated as such. Not every policy or ideology honors this. But there’s a downside to being human, too. Though we are capable of amazing acts of generosity, we can also commit appalling injustices and atrocities. We must acknowledge that and be vigilant.

It has of course been fascinating to watch the increased relevance of The Handmaid's Tale, but I regret the cause of it—the slide of the U.S. towards an authoritarian regime coupled with an oligarchy, and the abandonment of democratic ideals. We must strive to avoid a return to slaveries of various kinds.

I am very heartened by the kids under 20 who have been creating a whole movement of their own, specifically around the issue of school shootings. As for me, I hope to live long enough to watch the pendulum swing back towards true American greatness, which includes real democracy and a free and responsible press.

In 2015, you opened up about having suicidal thoughts during your Olympic career, and spoke about going to rehab after a DUI arrest. Now, you’re an active mental health advocate—what has this journey been like for you?

I’m somebody who has gone through pretty major depression spells. A lot of them have been after the Olympic Games, kind of coming off of that high. It’s something we’ve worked on for four years, and afterwards you’re like, “Now what the hell am I doing with my life? Where do I go? What do I do?” You’re just completely lost. And as somebody who was an athlete, where I’m supposed to be this big, macho, we-don’t-have-any problems, everything’s-perfect, we-don’t-have-any-weaknesses guy, I found it really taking me to this point of depression and suicidal thoughts. I think that I’m so happy now because I forced myself to become vulnerable, to make myself go through this experience and learn from it—why it was happening.

You know, when I checked into treatment I sent a text to my mom the day I got in, and I said, “Mom. This is the most afraid I’ve ever been in my entire life.” And I never got a response. Because I had to turn my phone off once I got there and turn it in. And the first few days for me were probably the most challenging days I’ve ever gone through because I didn’t want to talk to anybody—my walls were so high. And I remember eating by myself. I had my back to everybody when I was eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner the first few days. But eventually I wanted to give myself that chance to do something different for once—go through a change, no matter how scary it was. I guess it was maybe a little bit of my competitiveness where I was like I just want to dive in and see what happens. I let my emotions fly out, let stories come up, let anger happen, talked about everything that I was going through. After the second day I was all in.

What have been the positives that have come from speaking out about your struggles?

I have no problem getting up and talking about it. I like talking about it. It helps me. That’s one of the greatest feelings that I can feel because you’re helping somebody and potentially saving a life. When I die, if I can save one, five, ten, a million, 20 million, I don’t care—if I can save as many lives as I can, then to me that’s more important than anything I ever did in my athletic career.

I think for the longest time I wasn’t really showing all of who I was. And it goes back to that strong, I-don’t-need-help athlete mentality. I carried that for so long—but I finally let my guard down and was like, “I’m just going to show the world who I am.” Completely open and honest, for the first time. And you know what, quite frankly, if they don’t like it, I don’t care. If they like it, great. But this is who I am and I’m not going to try to be anybody else. If people can do that, then you’re going to be able to be happy through life, and you’re going to be able to enjoy every step of life like you should be able to. It truly is an awesome thing. I am so blessed to be able to have a family of four right now. I’m literally on a plane, we’re about to take off, and I’m so excited to go home right now to hug and see my family. To sit with our boys. That’s something I look forward to.

—Interview by Brady Langmann

What are truths about marriage that you’ve come to understand over time?

You always have to remember everything you loved when you first started the relationship, meaning you have to remember everything that you were attracted to, everything that was so special, that was so exciting and new. That needs to propel you past anything that starts to crop up as a relationship goes on, when everything’s not fresh and new. You have to be mature about that. I think some relationships go south just because there’s an inherent immaturity to the level of expectation. You’re so addicted to that original feeling of excitement that it has to happen over and over again, which is why I think some people go outside of their marriage for affairs.

One of my mantras is you have to love the imperfections. As we age, there are both physical imperfections and emotional imperfections that crop up. You have to program yourself not to have the knee jerk reaction of, “Oh brother, I don’t like that.” Love the vulnerability of the fact that you’re both aging now. You’re getting older, and there’s something sort of wonderful about that. It’s how you and the other person deal with it and compensate for it. I think it’s important that people don’t give up on themselves or on a relationship. You’re committed to a person, you love that person, you want to do what it takes to make that person happy, and you expect that coming the other way. You have to be committed enough to a relationship to want it to always work.

My mother and father were only married to each other their whole lives, and my dad’s whole thing was, “You should mate for life.” Laurie and I were dating for four years, and there was always that thing of should you get married, does it really matter? We knew we didn’t want to have kids, so why get married? But for me, when we weren’t married, there was always that feeling of, Yeah, I could go if something happened. It wouldn’t be a moral travesty if I moved on. I never liked that feeling, because you can expect that out of the other person. For me, marriage was a way of saying, “Now I am 100% committed to you.” Now it’s not easy to say, “Fuck it, it’s hard, I’m gonna leave now.” Marriage means I’m in, and we’re going to make this work.

Another key to marriage is that the thought of breaking your spouse’s heart has to be so abhorrent to you that it stops you from doing anything that would possibly make that happen.

What guidance would you give a young man thinking about asking someone to marry him?

I would say, “Make sure it’s for real. Take your time.” My wife and I dated and lived together for four years. We got to know the good and the bad; we saw whatever shortcomings there were, saw the strengths, and we were able to really weigh it out. It’s not something you should rush into, because relationships are always exciting at the beginning. Is it staying exciting? Or if it’s not staying exciting, is it staying solid? Is a good, healthy dependency growing between the two of you? Obviously you never want to be unhealthily dependent, but a marriage is about dependence. You do depend on that other person, and you want to be in enough situations where you see how they react. Is there a circumstance where you’d go, I just gotta run for the door? Chances are situations like that won’t reveal themselves until a couple years in. But if you’re tempted to run after two years, you’ve got to confront that and have some foresight. You really have to make sure that it’s right, and I think time is the biggest way to tell that. —Interviewed by Adrienne Westenfeld

In your new documentary, there is so much troubling material about how we treat the environment. How do you maintain any sense of optimism?

Doing the fucking work. I notice when I’m working on a part, for instance, I’ll be very anxious. And the way to scratch that particular itch is to go study your part, man. Work on it. That scratches the depression and the fear and all of that stuff. And you find that when you start to do that, you find accomplices all over the place—just like what we’re doing right now. But you’ve got to just do that little step of jumping in. You got to just engage, even if it’s something small. I ran across an interesting quote. I can’t remember who it was, but this woman said, “Passion is the flame that comes when you rub two sticks together.” So in other words, you’ve got to be rubbing the sticks before the passion comes.

Basically I’m a very careful, reticent cat. I mean, I wrote a song called “Drag Me to the Party,” to get me to do things. I’m certainly a guy who’s a selfish person, who’s addicted to comfort—I want to soothe myself, or whatever. So sometimes to go beyond that and to engage with something that’s not just directed to giving yourself pleasure or comfort, you say, “I didn’t like to do that,” but I notice every time I get tremendous amounts of joy from it. When I do resist my own selfish thoughts and put myself out to serve the greater good, I get fucking high man. It’s kind of something that all the religions have aspired to, right?

There’s pain and struggle in opening your heart, and it takes time, there’s seasons of it. There’s a slowness…. If you want the grass to grow, it’s not going to help going out there and pulling on the grass. That’s not how it’s done. So open your heart. Take action and do something. Be with other people. That is invigorating and it’s inspiring. –Interview by Alex Bleth

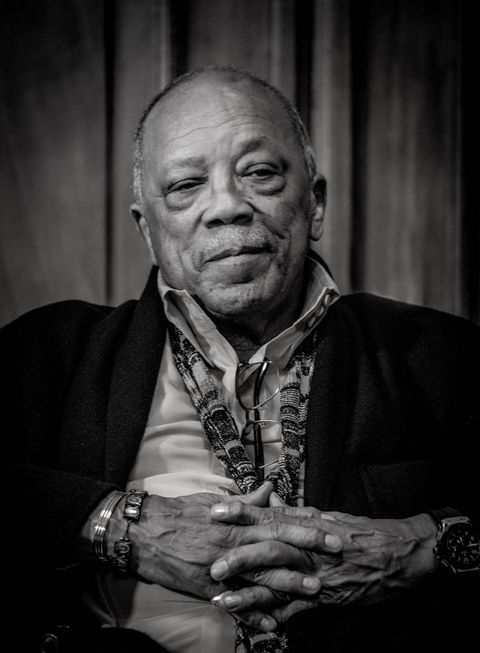

Making music has obviously been a passion of your life. Are there specific works/songs/albums of yours that are especially meaningful to you?

Everything that I’ve ever done has had meaning for me—otherwise I wouldn’t have done it. As an artist, you have to always be true to your heart and your soul. If you aren’t, you can’t hear God’s whispers. One of my mantras is that you have to have “Grace with your success, and humility with your creativity.”

What role does listening to other artists’ music play in your life?

When I was studying composition with Nadia Boulanger she would always say, “Quincy, there are only 12 notes. Until there is a 13th, listen to everything that everyone has done with those 12.” And that is exactly what I did. The only music I don’t like is bad music.

Any advice for non-musicians about how to listen and find meaning in music?

Music is the most powerful medium of all the arts. You can’t taste it, see it, touch it, or smell it. By its nature, all you can do is feel it. So turn off the smart phone and devices, dim the lights, put on your headphones, lean back and close your eyes, and let the music that moves you take you away.

What is the most important activity in life?

Reading. Especially Shakespeare, Milton, Chaucer, and Dante, or for that matter Cervantes, Leopardi, Jane Austen, and George Eliot. And rereading. Go outside somewhere, particularly if it’s poetry, and read it out loud to yourself so you’re not bothering anybody else, at a distance from others, and listen to it. You know. Get it into your inner ear. Give it a home in yourself.

I think the only thing I’ve been able to achieve in almost two thirds of a century of teaching is the feeling that somehow at very good moments as I teach or as I listen to my students speak to one another, that somehow I and they are inside the poem, or we are inside the play, or we are inside the novel, and that is magnificent.

What is the most important question in life?

I would think the most important thing in the life of any human being is whom you marry. But even that perhaps in the end depends upon what she or he has read, or what you have read, or what you’ve understood, and where you find common ground. For me, Shakespeare is the final authority. More even than Tanakh, the Hebrew bible. Or Dante or any possible rival. I think Shakespeare demonstrates what you will have to call the human superiority of women to men.

All of the women in him, even the one who turns so bad, Lady Macbeth, they have to marry down because—with maybe two exceptions, Falstaff and Hamlet—the men are simply not up to the women.

Juliet is amazing. Here’s a girl of 14 or 15 who is wiser in matters of the heart than almost anyone alive today. “My bounty is as boundless as the sea,” she says of her love for Romeo. “The more I give, the more I have for it is infinite.” Any human would wish to hear that from another human.

What about the flip side of love?

I suppose there’s always been a great deal of hatred in the world and in the United States. But now, at 88, I feel it more strongly than ever before. I don’t hate anybody. I mean, it’s hard not to hate Trump—and his debasement of public discourse—but it’s not worth hating Trump. Hate is not good for you. It’s banal to say it, but in the end, we’re surely here to love one another.

And beyond loving one another, do you believe in God?

My wife Jeanne is an admirable and honest atheist. I’m not an atheist. My attitude towards Yahweh is that I don’t like him and I don’t trust him, and I wish he would go away. But I know he won’t because he’s built into the language, as Nietzsche said. He’s part of the way we think. As soon as you use a verb involving being, you’re in trouble. When he identifies himself to Moses he says “Ahyh asr ahyh [spelling?],” punning on his own name of Yahweh. It means something close to, “I will be what I will be.” Which in effect means “I will be present whenever and wherever I choose to be present,” which has the horrible corollary, “And I will be absent wherever and whenever I choose to be absent.” And he—or whatever it is, she—has certainly been absent for a long time.

I am fascinated by the Bhagavad-Gita, its wonderful distinction between three states of being, what it calls—what’s the word used in that admirable translation? I can’t read Sanskrit, I regret to say. Dark inertia! Dark inertia, passion, lucidity, those are the three states. Most of our lives, certainly of my life, I live in a state not of lucidity—though I try—but of dark inertia. And often, too, in a state of passion, which at 88 is absurd. —Interview by Jay Fielden.

In 2010, I was sent by the AP to Haiti to help cover the catastrophic, 7.0-magnitude earthquake. I ended up writing a narrative piece on the quest to find the missing people who had died inside Hotel Montana, the country’s best hotel. At that point I had been dating Mickael, my future husband, for three years and it was clear that he was someone precious to me. As I reached out to the families of the missing, I stumbled into love story after love story. What struck me about them is how it was not the over-the-top romantic gestures that people miss when they lose a loved one. It’s the simple, undramatic moments of a shared life.

I have been a foreign correspondent since 2006, first covering West Africa and now covering ISIS, from my base in New York. My accountant—who has instructed me to keep a travel calendar so that I can get a refund on my state taxes—will tell you that since 2014, I have been away on average for one-third of the year. Mickael and I stay in touch through regular text messages, What’s App, Facebook, and Skype. In addition to daily expressions of love, we share the mundane details of our day-by-day trajectory. He texts me to tell me that he signed up a new client or that our dog killed another squirrel. I text him from a checkpoint to complain about how long it’s taking to cross.

Among the reasons that our relationship is so precious to me is that Mickael is proud of the work I do, and he understands that some level of risk is necessary. I am always aware of just how rare this is when I speak to my fellow correspondents, many of whom are either single or else who are perpetually cutting trips short in order to accommodate a less-supportive partner.

Returning is always one of the sweetest moments. Mickael always cooks me kedjenou, our favorite Ivorian stew. If he is free, he picks me up at the airport and we ride home holding hands the whole way.

For years I held on to the beat-up Nokia cellphone, which was the phone I had when we met, and which had the sweet text messages he sent me as we were just getting to know each other. I used to scroll through them to remember those amazing early moments, and to linger in the miracle that happened: A girl from Romania, who grew up in California, met and fell in love with a boy from Cameroon, living in Senegal. —As told to Eric Sullivan.

Jay and I met several months ago. He’s the editor of the magazine you’re reading (or flipping through at a Hudson News in some east coast airport.) Don’t worry, I never know who the editors of magazines are either. Anyway, I was nervous about the meeting. I had just gotten in a fight with my girlfriend because I had fucked something up. I was feeling less than manly—and I was meeting the editor of the men’s magazine. I grew up with Esquire. It’s always had on its cover and throughout its pages, in glossy photos… men. Manly, have-it-all-together men. Confident, not cocky. Men in suits and boardrooms and by billiard tables and in cafes and in front of raw canvas they would stretch to create masterpieces. And here I had a meeting with the editor and I couldn’t have felt less masculine. There’s nothing like fucking up in a relationship to check your masculinity: the soft, dumb little boy emerges. And he had a meeting. Well, good luck kid.

But here’s the thing. Ready, set? It’s in moments like this that I shine. Because I have a super power: mess. Or rather, my ability to flourish in mess, roll around in it, revel and bask in the messy nature that is being a human. I’m good at it. And it really wasn’t til I discovered and embraced this that I became successful.

Earlier in my life I thought being successful was all about showing off. The self-help books I’ve read (oh, there have been many) have all said, Ya gotta be confident. I think as a nation, we’ve drunk deep from the Kool-Aid on this, and have become overly confident. So often we forget that we all share the innate inability to understand how to live, and the world feels like a warmer safer place when we occasionally step back from the ledges of leadership and poise and impressiveness and recognize that. That, at the end of the day, we’re all kinda idiots at this. There are no answers. We were given no manual, no dress rehearsal to get it right. We’re all just fleshy bobble-headed animals with too much brain stumbling towards some sense of meaning, usually personal, sometimes universal.

I have deepened my heart and empathy over the years through failure and through exploring that which makes me unsure. It’s allowed me to focus more on honing the question as opposed to patting myself on the back for having the answer. And I’m lucky. It’s my trade—the shameful and silly and messy thing of being a human. I’m an actor. I’m a storyteller. And I’m really only drawn to stories with a little (or a lot) of blood in them.Heart. I’ll even say “soul,” which, as my cynicism depletes over the years and is replaced by some sentimentality (read religion), I actually believe we have. And I believe the meek shall inherit. Well, maybe not the meek. Maybe the insecure—those who acknowledge their limits. The self-effacing.

So, I sat in front of Jay. And instead of putting on a show, I used my super power and I leaned into the mess. I talked about my weaknesses with Jay. About my mental illness and the stresses its put on me and the people I love. About my arrogance, my anger, my unpalatable emotions. About my love handles, and my ever multiplying chins. About my struggles in relationships. About my inability to fit in. About all the stuff that’s made me doubt. About my loneliness, my fear, and my inability to understand how to “do” the heteronormative agenda that my Facebook friends have all figured out: how to have a family, how to take it easy in life, how to enjoy things, how to own a home, how to take up golf or something.

And after all this non-manliness, Jay asked me to write something. About creating a meaningful life. Well, mine began with loving my garbage, digging in the trash that really really makes me uncomfortable and finding the beauty of it. The conflict, the doubt, the mess, this aching, terrific, brutal thing that is being a man in the world.

You have had victories, in the course of your career, and you have undoubtedly had setbacks. Which is harder to process, and why? How do you survive a setback?

Setbacks are obviously more challenging to who we are, but they allow for more growth, to help us move forward and learn new things about ourselves and about the world. Without setbacks, we will never learn. I have failed many, many times in my life, but I am not ashamed of this. Every failure is proof that we tried something–if we are not trying, we are not failing—but we are also not succeeding. So sometimes I am actually excited to fail, to try something new and not know if it’s going to work out. This is the only way to grow outside of ourselves. When something doesn’t go as planned, you can do two things: you can hit your head against the wall and feel sorry for yourself, or you can say, “Great, now I’m free and ready to start something new.” I prefer not to fail, but if it happens, I always prefer the second option.

How has your viewpoint on food changed? Did you think differently about food & cooking when you were, say, 21 years old? What's different now, and why?

When I began cooking long ago, when I was 15, you became a cook by learning French cooking. While that’s an extensive education, I realized that Spanish cooking was obviously as good and full of dishes, techniques, and history worth a lifetime of learning. Then Italian, too… and Turkish, Greek? Regional cooking and writing? And Asian, African, South American? Oh my god, it’s impossible! I’m 49 now and I know that as I grow older, I realize how much I don’t know—and I came to realize that I will never really learn it all. That’s humbling.

The difference now is that if you don’t learn it’s because you don’t want to–there are so many ways to learn about the diverse world of food today. You can travel, study in school, go eat out in restaurants. Now we even teach food physics at Harvard, food politics at NYU and George Washington University. Now food is art, politics, science, hunger, health, diplomacy, and war—food is at the heart of it all. Now that we are more aware of it, we can really vote with our plates like we never have before.

How has your source of meaning changed, over the years?

I’ve felt like an immigrant all of my life, even in my native Spain, after I moved from Asturias to Barcelona as a child. When I was young, I sailed with the Spanish Navy and saw America for the first time–this put me on a path to want to come back, start a business, do something big with my life. But when I was on that voyage I also saw places where I understood real poverty—this was an early lesson for me that the world is a difficult place for many people. Over my life I’ve pursued the American dream, but I’ve also started imagining this new version, where we aren’t just working to help ourselves and those we love, but also those who we’ve never even met. That’s the new American dream. Life should not be just about supporting our loved ones–if we have the ability, we should reach out beyond our circles and show generosity, show humanity.

With that goal in mind, what is something that everyone should do?

Give yourself to others, volunteer, donate, get involved with a cause you believe in. Whatever you have, give some of it away – time, money, voice, passion. And don’t just become a seal clapping for everyone who agrees with you. Work out of your comfort zone. We all are rich in something—it may not be that you can donate money to a cause, but somewhere within you have a talent; use it for the wellbeing of others. Less talking and more doing! If you have just a few extra hours a week to give away, volunteer and show your support that way. Believe me, when you step over the line of your comfort zone, that’s when you wish you would have crossed it sooner because now you are a part of two worlds. You are a bridge that connects both of these worlds and you can now become the force that improves both of them. —Interview by Jeff Gordiner

From what have you derived meaning and sustenance over the years, and how has that changed over time and especially now in this moment where facts are suspect and anti-intellectualism is cutting into what many believe is the stuff of progress (education, collaboration across ethnicities, globalism, a free press, protecting civil rights, scientific inquiry and a respect for it, etc.)?

We focus on what we see as invidious change, make it a trend, dignify and enlarge its presence in the culture and generally fascinate ourselves with what we dread, making concessions to it, adopting its terms. Everything you name is always resented. And it is always fruitful and good. Under attack, it should be celebrated and enhanced. We should have much more confidence in the value of what we call our values. I am mystified by the readiness with which they are compromised or abandoned by their supposed loyalists.

What advice do you have for young men now? Where would you send them to better understand the forces out there that are asking them to reimagine what it is to be a man in America?

The question should probably be recast as advice to young people, not for the sake of gender neutrality but because traditional gender-based identity is being questioned on every side. This makes a profound demand on individuals to understand who they are without the props and limits tradition has provided. We look back at the past and see distortions of personality, deprivations, and injustices. True enough. But it is true also that many men have done an honorable job of being men in America. I think it would be helpful now to acknowledge this. The polarizing of virtues, thinking of men as strong and women as sensitive, is obvious nonsense. Men have written some very fine poetry, some glorious music. If we insist that American male-ness is crudeness and swagger, we are denying them models of generosity and idealism they have a right to and a need for. It is gratifying to live in a time when women’s history is being explored in order to provide a larger, truer sense of what women have done and might do. I have felt the effects of this in my own life. Young men would also benefit from a truer, fuller exploration of American history, with attention to everyone, male or female, who lived a life worthy to be called good.

I write this as the mother of sons. But if this civilization has learned one thing of great value in my lifetime it is that negative stereotypes are profoundly destructive on every side and in all cases. The male stereotype tends to forget that not all men are white. I wonder if our terrible readiness to imprison black men is at least supported by a general forgetfulness of the fact that any young man is a soul and a spirit, not to be deprived of the goodness of life without true religious dread of the gravity of that decision.

Is the discipline of having faith--in others, in yourself, in human progress, in those things we can't know, in mystery--at its richest now? Most tested?

Certainly many things are being tested now. I had no idea that our system of government depended so heavily on respect for it among our political class, the people who ask us to trust them with it. The lesson has been very harsh and abrupt. I also had no idea that my own sense of self was so deeply entangled with my confidence in this good, flawed country and its very profound project of working toward its ideals. But this may be a lesson we needed to learn. A democracy is necessarily dependent on the good will and integrity of its people. This country has been so strong and seemed so stable that we have been giving too little thought to the fact that we have to sustain it in every decade and generation. The realization is upon us now, keener with every scorned decency and violated norm. The best thing about America is that, pushed to define it, we always come back to a few magnificent ideas. These ideas are alive and flourishing in that great deep state, the general population.

What does age and aging give? Even as it takes? It’s not for sissies, but what are its consolations, its graces, its mysteries as felt in daily life?

I have been very fortunate. I know how this ends, but so far I have enjoyed good health and as much serenity as these strange times permit. I am so old that I remember my father’s chagrin when Truman beat Dewey. I remember wearing an I Like Ike button, seeing Fidel Castro on Ed Sullivan’s variety show. I was politically precocious, an unattractive thing in a child, but at least I can say that I have been an attentive witness of modern American history. I remember America before the interstate highway system. I saw orange juice come on the market as a consumer product. To see so much change and the effects of change, most of them very good, is a lesson in the nature of culture and civilization far too complex to parse, but fascinating anyway. —Interview by Amy Grace Loyd

I am suspicious of virtue. Doubtless this lifelong skepticism about people who claim to be driven to do good hails in part from having grown up in a professionally religious family (of a liberal Democratic bent). But this aspect of my background has sometimes been overemphasized, given that I disavowed any allegiance to organized religion by about age eight. For the pursuit of virtue as a guise for the pursuit of admiration, status, superiority, power, self-glorification, and the opportunity to push other people around is hardly restricted to the clergy.

Coming of age at the tail end of the Sixties, I was as self-righteous as anyone else who ponced around with placards about promoting the standard raft of leftwing causes—opposition to the war, environmentalism, civil rights. But in retrospect, what I value about that era has little to do with my generation’s preening pursuit of justice. Instead, I fancy the period’s anarchy, mischief, curiosity, and celebration of pleasure. We positively invented creative destruction. We upended things for the hell of it, and not always to make “a better world.” Ambitious for my future, I was cautious, even cowardly in relation to substances, but if I had it all to do over again, I’d have done more drugs.

My own prime directive has never been to do good, if only because the nature of goodness isn’t always self-evident. I don’t understand the appeal of getting all fired up about a set list of prescribed orthodoxies in a militant, predatory spirit, and stalking the internet for sinners. It’s all so bloody joyless. Nothing wrong with voting for the party of your choice, or having a stimulating conversation over a bottle of wine about how on earth to eliminate single-use plastic. But I want to take aside these huffy millennial motherfuckers crusading their lives away on Twitter and say, “Kids? Your knees aren’t shot yet. You’re wasting your youth.”

From an early age, I have been willful. I don’t like being told what to do, and that includes what to think and what to write. I resent having other people’s version of virtue imposed on me. If I have, however inadvertently, accomplished a little good recently, that has been by championing not only my freedom but everyone’s freedom to arrive at their own version of goodness, maybe to decide goodness isn’t even their bag, and to look behind the pretence of goodness to discern the vanity, the self-aggrandizement, and sometimes even the malice that lurks behind it.

My generation prided itself on its nonconformity, though in many ways we were as slavish to the times as the generations before us; we all wore bellbottoms and beads. But at least we paid lip service to going your separate way, questioning authority, and coming to your own conclusions about how to build a meaningful life. Belligerent by nature, in adulthood I’ve taken that different-drummer cliché to heart. If I owned a car, my ideal bumper sticker might read, “Get your bossy identikit opinions out of my face.” (I seem uniquely blessed with the capacity to enrage people. It’s an interesting quality. I don’t do it on purpose.)

Suspicion of virtue doesn’t have to translate into being an asshole. I’m loath to hurt a friend’s feelings; I never litter; I try to remember my mother’s birthday. Yet I think we could all agree that, however exhilarating at times, life is often very hard. No one knows what it’s for, or what we’re supposed to do while we’re here. There’s no user’s manual, and if anyone gives you one, you should throw it away. By the time you figure anything out, you’re dead. So if I operate in accordance with a single moral rubric, it’s “For pity’s sake, at least try not to make life even worse than it has to be.” I dislike religions—and the contemporary hard left qualifies as a church—because I see them as making life even worse than it has to be.

I’ve always aimed not to do good but to do well. I treasure playfulness, subversion, deep thought, having a good time, and trying not to repeat myself. The nicest thing ever said about my books is that they are funny. That means my novels have collectively improved the experience of being alive by a smidgeon. That’s the closest I come to goodness—and I have to say, that’s pretty fucking close.

Most of us don’t take part in philanthropy for one reason or another. What drew you to it, and how do you encourage others to give to causes they believe in?

I came to realize that business is the greatest platform for change and that corporations can have a huge positive impact on society beyond their products. That's why I created the 1-1-1 model at Salesforce—devoting 1% of Salesforce's time, products, and equity to giving back. When we started, it was easy: we didn’t have employees, products, or market capitalization! Today, however, Salesforce has more than 30,000 employees, more than $100B in value, and our 1-1-1 model has translated to millions of hours volunteered, hundreds of millions of dollars given to charity, and more than 30,000 non-profits running for free on Salesforce. I've never had to look back and ask if Salesforce was giving back, and I've never had an employee say we aren’t doing enough.

How do you balance doing what you think is right versus what may or may not be good for your business?

Do you trust yourself? Is trust the highest value you hold as a leader? How about your company? Is trust your company’s highest value? When you trust yourself, you can take solace that you can stand up for yourself, your company, and do the right thing. The right answers are always inside us, and they are validated by the responses that you get when you take action. You have to find it within. I remember getting a call from one of our top executives in Indiana who told me that I had to get involved in preventing discrimination of the LGBTQ community in the state [following the passage of Indiana’s “Religious Freedom” law in 2015]. Initially, I wasn’t sure whether to get involved. But then I went within myself, asked those questions, found my center, and sent out a tweet [in which he said Salesforce would “dramatically reduce our investment” in Indiana]. While I was confident in my position, I didn’t realize that the next day so many others would fully support me. At the end of the day, it all came about because I trusted myself. But the opposite is also true—when you don’t trust yourself and are always looking for outside guidance to do the right thing, you never will.

But outside guidance, or inspiration, can be important in a career, and life in general. Have you had mentors?

I've had so many mentors in my career, and I’m deeply grateful that they took an interest in me. One of the most important has been Neil Young, the musician. It took me a while to understand why the ideas he had for me were so powerful. What I realized was the Neil was truly an innovator, and that he innovated supremely in music. I've also seen Neil innovate in automobiles with LincVolt and even technology with his Pono and Archives programs. He even wrote several books, including a novel. One day it occurred to me that Neil was innovating the same way I was: by deeply listening. He deeply trusts himself, and he takes action in what he believes in. He's taken political positions that have not been popular, and he's never been afraid of the status quo. He often calls me to encourage my work, or give me feedback on ideas I've had. In my office, I have a poster that I bought at the MusicCares auction and it has one of his favorite quotes--“Do whatever you want. Neil Young.” —Interview by Kevin Sintumuang.

What do you know and understand now that you wish you’d known and understood in your youth?

I wish that I’d known to take joy wherever and whenever I could find it. I was a product of the late twentieth century where we thought we could save the world without taking the time and care to save ourselves. We and the world suffered for that. I’ve learned that joy is not a luxury or a privilege but a life-giving, resilience-making human birthright. And I’ve never met a wise person who doesn’t laugh often and smile easily–including at themselves.

How do we know when we’ve grown wiser? Is there any way to measure how we’ve changed?

Wisdom is something different from intelligence or accomplishment or knowledge, though it may be in possession of those. The point is, they are possessions, qualities you can point at. The measure of a wise life is in the imprint it makes on other lives around it. It’s not about having a perfect life or how much you have overcome; it’s about integrating all that happens to you into your sense of wholeness – tending the intersection of inner life and outer presence in the world, and inspiring that in others. And following on my answer above, if you think about the wisest people you’ve known up close, in your mind’s eye they probably have a smile on their face. That’s a lovely litmus test: If you smile more easily than you used to, you might be on the right path.

As you get older, do you still seek out feeling young? What keeps you feeling young?

When my children were going through the metamorphosis of adolescence, I made a decision to try to be fascinated rather than terrified. I’m trying to do the same with myself in the metamorphosis of aging. One of the things people rarely talk about is that however old we grow, most of us still feel 16 or 21 in spirit--so it’s jarring to wake up every morning to physical evidence to the contrary. On the other hand, it’s a relief to feel 16 or 21 inside and also have the knowledge in your body that life is long. I would like for my skin and hair to stay young, but other than that I really like how I’m able to take delight in ordinary, everyday pleasures in a way that eluded me for the first half of my life. I’ve heard that this is a process that comes with age in our brains--that we become less motivated by novelty and find greater satisfaction in what is given.

A great source of what energizes me now is friendship. I enjoy my friendships more--I enjoy people altogether more–and I am a better friend than I used to be. I’ve always had friends who were older, and at this stage of life I’m starting to have beautiful friendships with people who are much younger. This does feel like a way not to stay young but to stay vital, to keep learning and loving, and to offer what I’ve experienced in companionship with the world that is becoming. —Interview by Adrienne Westenfeld

I just turned fifty-three and I am somehow in my thirty-fourth year of parenthood. Being a 19-year-old working class dad meant foregoing some things I wanted out of life — mostly travel and education—to provide for the little birds, but in hindsight, it also gave me the ingredients for my own purposeful life: selfless love, responsibility and, most of all, hope. As a parent, hope is not some cheerful outlook but a desperate necessity. In hard times, when I tell my kids, We will get through this, it isn’t inspirational doggerel, but the fiercest determination I feel.

My own father is at the end of things. He has Alzheimer’s Disease and a host of other ailments and has fallen further than I ever imagined the old sailor and steelworker could fall. But at least twice a week I take him to his favorite dive bar for one rum-and-coke (him) and one whiskey-rocks (me). We play forty bucks worth of 25-cent pull-tabs (low-stakes tavern lottery tickets) and we look around the bar and talk about the same things—my mother, who died twenty-one years ago (at 53, the age I’m at now), my brother and sister, and the sickening state of politics. (My dad is that vanishing breed, a staunch labor Democrat.) If I’m about to go out of town, we say goodbye as if it’s the last time we’ll ever see each other. You’ve been a good son, he’ll say. You’ve been a good father, I’ll say.

One time in the bar, he stared at me and his eyes became rimmed with tears, and out of nowhere, he said, But you had a good life, right? And in that moment, I saw the same hopeful desperation I feel in my own fatherhood, that after all of that scrambling and working and longing, all of it—you just … want … that. Not perfection, not SAT tutors or private coaches or low interest rates or some version of a tree-lined suburban stumble-free childhood. Just a good life. I have, Dad, I said. Good, he said, me too.

As a first-generation college student, the son and grandson of high school dropouts, I’m proud that I have one kid working at a college, one about to graduate college, and one starting college. After the 2016 election, my son was 16 and the only one at home, and I was surprised that he was just as upset by Trump’s ludicrous election as his older, and at the time, more politically aware sisters. I said to him the thing we say a hundred times as parents: I know this is a hard time, but you’re going to be fine, and he looked at me as if I were insane. I’m not worried about me, he said. It took my legs out, as it did when my middle daughter ventured out on her college campus to protest, and my older daughter stood up for immigrant students at her university job. Each of them, in this hard, fearful time, has channeled anger and sorrow into the desire to fight, to stand up for others. Seeing this, how could I not aspire to do the same?

I’ve been a writer at least as long as I've been a parent—although I was a far better dad than I was a writer most of those years, thank goodness. I only know that I haven’t really thought about something until I’ve written about it, and that my clearest understanding of life is always another rewrite away. I’m drawn to what Camus called “the wager of our generation,” so I’ve written novels about the terrorist attacks of September 11, about violence against women, about the 2008 financial crisis. I’ve also written about class, romantic love, parenthood, and childhood. I am writing a novel now about youthful protest and I just finished a long hopeful short story about climate change. Mostly, I find my writing is drawn these days toward the two magnetic poles of parenthood, and maybe of any meaningful life: the hopefulness needed to imagine a better day and the courage and energy needed to fight for it.

You’ve said that corporate giving should be the norm, but many companies are disinclined to give and resistant to change. How can your vision become a reality?

Corporations don’t have much of a choice. By 2020, over half of the working population will be millennials. Those 18-35 nurture different expectations. They grew up with the idea they should change the world, and that disruptive dimension is now entirely part of their operating system. This cultural shift puts pressure on corporations who seek to attract and retain these youth as employees, as customers, sometimes even as investors. Millennials refuse to consume brands that do not cultivate social impact; they refuse to join companies that fail to register social good as a tangible driver of their operations. If companies want to remain competitive and relevant in today’s world, they have to adapt.

Some criticize corporate giving as inherently self-serving, a way for companies to virtue-signal. How do you make sure that businesses who give back are in it for the right reasons? Does it even matter?

Ultimately, no, the motivations do not really matter to me. Selfishness? We’re all selfish to some degree. A business plan? It’s natural that they do all they can to ensure the prosperity of their company in the face of increased competition. It’s not for me to second-guess why people and corporations are giving. What matters to me is that they have realized that they can no longer disregard that social disruption and that they start building a better world for tomorrow.

How can someone who doesn’t have much disposable income give back?