Norman Rockwell’s masterpiece “The Gossips” enshrined gossip right up there with baseball as a hallowed American pastime.

Now that place is cemented, courtesy of a Decatur technical college: A National Labor Relations Board administrative judge has ruled that the school can’t fire an employee for engaging in gossip.

According to NLRB Judge Donna N. Dawson, the “no-gossip policy” of Laurus Technical Institute infringed on what the National Labor Relations Act calls “protected concerted activity.” That’s workers’ right to act together to maintain or improve their pay and working conditions, with or without a union.

So for now – the case is under appeal – employees in Georgia can feel free to dish to co-workers about their crappy jobs, their boss’ weight or the alleged affair going on down in accounts payable.

Officials at Laurus would not comment on the case, and Joslyn Henderson, the employee who initiated the complaint, could not be reached for comment.

“I thought this case was interesting, but not shocking,” said John Koenig, a labor and employment attorney with Barnes & Thornburg in Atlanta. “The NLRB has been on a consistent streak, under the Obama administration, of shooting down employers’ policies that put limits on employee speech.”

In Rockwell’s painting, originally published on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, a piece of gossip wends its way through more than a dozen people, right back to the original snitch. It’s anyone’s guess what juicy tidbit they’re repeating, but their wide-open faces suggest that it’s downright innocent, compared to the industrial-strength gossip spewing from today’s airwaves via outlets like TMZ, the Wendy Williams Show or even The View.

Take the infamous elevator confrontation between Beyonce’s husband, Jay-Z, and her sister, Solange. It seemed that half of America had no more pressing problem than to get to the root of what started the fight. (Beyonce is not commenting, so no one has a clue yet.)

Hollywood may be ground zero for American gossip-mongers, but Washington isn’t far behind. Filmmaker Patrick W. Gavin, spent five years trolling the capital’s fishbowl as a writer for Politico’s gossip section, “Click.” Before it was disbanded in December, Gavin was one of six journalists assigned to it.

“What I have always noticed in D.C. is the first thing people say when they bump into you is, ‘What do you know?’” Gavin said. “It is a really lame way to start a conversation, but if you don’t have good dish, you are useless.”

The policy that got Laurus in trouble said, in part: “Gossip is not tolerated at Laurus Technical Institute. Employees that participate in or instigate gossip about the company, an employee, or customer will receive disciplinary action.”

The school laid out a rationale for the prohibition, saying gossip “can drain, corrupt, distract and down-shift the company’s productivity, moral, and overall satisfaction.” But that wasn’t enough to satisfy Judge Dawson, who wrote that the policy “is overly broad, ambiguous, and severely restricts employees from discussing or complaining about any terms and conditions of employment.”

Henderson, whose job was to sign up new students, had worked for Laurus for more than five years when she was fired in November, 2012.

Documents in the case chronicle a history of conflicts between her and company management, including allegations that Henderson encouraged coworkers to apply for jobs at a competing school.

But Judge Dawson found that Henderson was motivated by concerns over workplace conditions and job security. Furthermore, she wrote, all Henderson’s actions were protected by legal precedents, including rulings striking down employers’ attempts to outlaw “false, vicious, profane, or malicious statements,” ” “disrespectful conduct,” “negative conversations,” “derogatory attacks” and “disparaging comments” about superiors or colleagues.

But even if gossip is legally protected, some workers shy away from it.

“I don’t like to engage in it,” said local writer Alyssa Johnson. “I know if I am talking about someone else, I can easily be talked about, so I limit the amount of gossip that I take in and give out.”

Nevertheless, Johnson said, she has watched a shift in corporate America that has ushered in a more laid-back attitude toward gossip — thanks, in part, to social media.

And she knows that for many people, gossip can fill a void. “Who doesn’t like a little juicy dirt?” she said. “It can make you feel better about your problems.”

Then there are the workplaces where gossip is unavoidable, even expected.

Douglasville hair stylist Roxana Murfree Alston has her tongue planted firmly in her cheek when she claims: “We don’t gossip. We just get the scoop on things and give advice.

“Of course gossip is part of the culture,” Alston said. “The salon is a place that the clients feel comfortable talking to their stylist about mostly anything, from health to personal issues to relationships. Sometimes it stays between the client and stylist. Sometimes we share.”

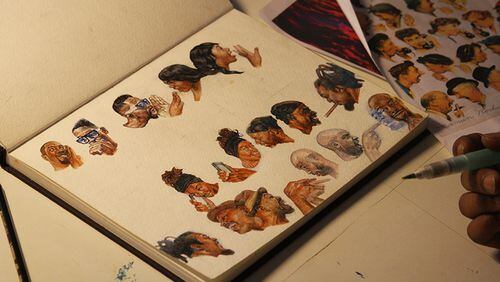

Fabian Williams has been out of the corporate world for a while and now works as a full-time artist. But he remembers the joys and pains of good gossip.

As an homage to Rockwell, Williams is working on a painting that recreates “The Gossips,” using his friends as models.

“Gossip is totally different now in terms of how it circulates,” Williams said. “Some simple office chat could go viral, if it strikes the right amount of absurdity. You can be embarrassingly world famous on a simple mistake.”

About the Author