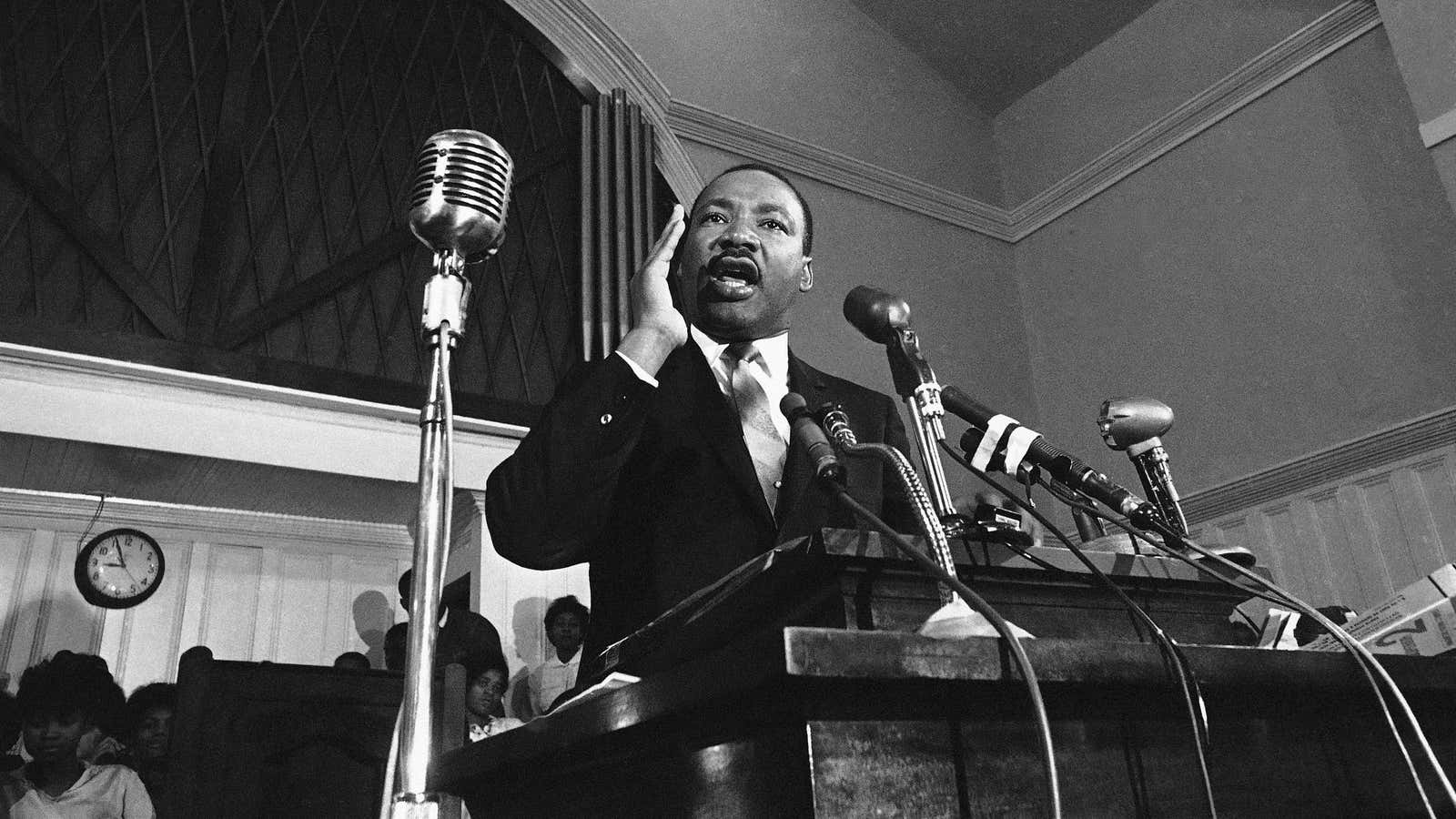

Only three people have a US national holiday observed in their honor: Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day is celebrated on the third Monday in January each year (near his Jan. 15 birthday) to honor his legacy in battling for civil rights. The fight to create a national holiday was a massive struggle, one that required the same commitment as the movement to guarantee the rights of all Americans: community organizing, long-term determination, and relentless persistence.

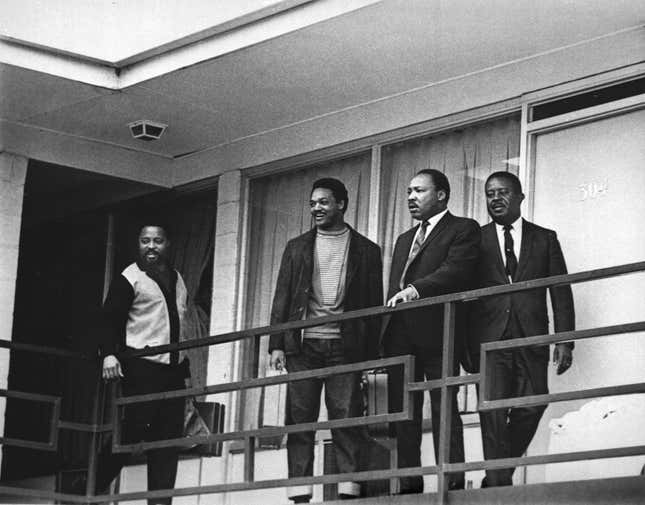

King was assassinated in 1968. The legislation designating the federal holiday in his honor wasn’t passed for another 15 years, and the day wasn’t officially commemorated until 1986. And even as King’s work continues to inspire generations of leaders, the fight for universal recognition of the holiday in the US still isn’t over.

A struggle from day one

The call for a national holiday began shortly after he was shot on April 4, 1968—congressman John Conyers, a Michigan Democrat, introduced legislation just four days later. Congress took no action.

Conyers then was one of the few black members of Congress. (He would serve for more than 50 years, resigning in December following sexual-harassment accusations.) Conyers was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). When the legislation stalled, he persisted, introducing the same bill every year until its passage 15 years later, gathering more co-sponsors along the way.

The only African-American senator at the time, Massachusetts Republican Edward Brooke, also introduced legislation in 1968 to authorize the president to proclaim Jan. 15 a day of “public commemoration” in honor of King, His bill didn’t go as far as to designate it as a legal holiday.

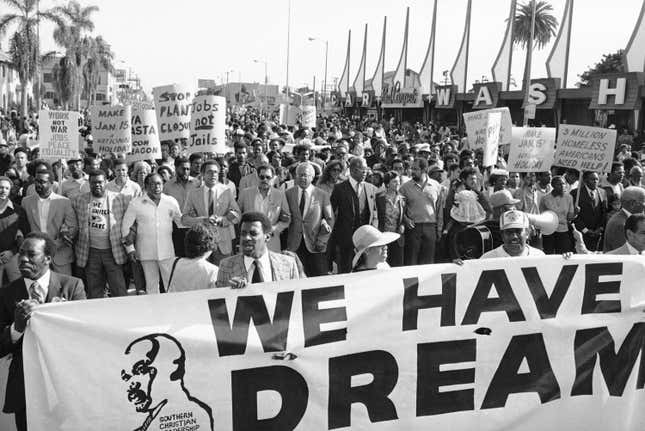

The congressional caucus played a pivotal role in gathering public support, advocating for the holiday around the country with debates, demonstrations, and petition drives. In 1971, the Southern Christian Leadership Congress (SCLC) presented Congress with a petition in support of the King holiday bearing over three million signatures. Still, Congress took no action.

The birthday song and the big push

By the late 1970s, calls for a national holiday were mounting. The CBC had collected over six million signatures, and president Jimmy Carter endorsed the holiday bill.

Coretta Scott King, King’s widow, launched a national campaign to gather more public support ahead of the 15-year anniversary of his death, delivering multiple speeches to Congress and holding rallies across the country.

Stevie Wonder regularly performed at the rallies, telling an Atlanta crowd in 1979, “If we cannot celebrate a man who died for love, then how can we say we believe in it? It is up to me and you”

Wonder released his new song “Happy Birthday” to celebrate the life of King on his 1980 album Hotter than July. The record’s sleeve featured a photograph of King with a message imploring fans to support the holiday bill: “We still have a long road to travel until we reach the world that was his dream. We in the United States must not forget either his supreme sacrifice or that dream.”

Later that year, Wonder called Coretta Scott King and told her, “I had a dream about this song. And I imagined in this dream I was doing this song. We were marching—with petition signs to make for Dr. King’s birthday to become a national holiday.” She wasn’t optimistic: “I wish you luck. You know, we’re in a time where I don’t think it’s going to happen.”

But the song was a hit, and public support for the holiday reached a fever pitch.

At last

In 1983, civil rights leaders gathered in Washington, DC to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the March on Washington and King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, as well as the 15th anniversary of his death.

Following the anniversary, legislation was once again introduced in Congress, but this time it was different.

When senator Jesse Helms, the North Carolina Republican, tried to add FBI smear material on King (the agency spent years trying to discredit him as a communist and threat to US national security) to the congressional record, his New York Democratic colleague Daniel Patrick Moynihan threw the pages on the floor, calling them”filth” and ”obscenities,” and left in disgust.

The next day, the bill passed easily, and president Ronald Regan signed it into law on Nov. 2, 1983.

The fight continues

The first federal holiday wasn’t celebrated until 1986. In 2000, 32 years after King’s death, South Carolina became the last state in the Union to formally recognize MLK as an official holiday.

The first Martin Luther King Jr. Day was marked with marches, church services, candlelight vigils, and concerts across the country. Hundreds of thousands of people gathered in Atlanta, King’s hometown, where Coretta Scott King awarded South African bishop Desmond Tutu the King Peace Prize for his work against apartheid.

Not all Americans took part in the celebration. In Buffalo, NY, a sculpture of King was whitewashed. Southern states immediately introduced legislation that combined MLK Day with state holidays to honor Confederate general Robert E. Lee.

Even today, Martin Luther King Jr. Day faces resistance. States like Mississippi, Alabama, and Arkansas continue to combine Confederate commemorations with those for King; Lexington, Virginia honors Confederate general Stonewall Jackson with a parade the weekend before MLK Day.

The fight for recognition of Martin Luther King Day continues, just as does the struggle for the very same ideals King championed.