How One Man Overcame a Prostate Cancer Death Sentence

When Todd Seals received his death sentence, he was shocked but not surprised. For months, he’d suffered a relentless cough, excruciating back pain, and episodes of tunnel vision. When he started urinating blood, he knew he could no longer maintain manly denial.

At his doctor’s office, chest X-rays revealed so many spots on his lungs that it reminded Seals of “Chester Cheeto.” Two days later, Seals got a call at work with more test results confirming the worst. His PSA level was 800 times above the recommended cutoff. His prostate gland, normally the size of a walnut, was nearly as big as a softball and was compressing spinal nerves. Bone scans showed tumors riddling his spine. Diagnosis: highly aggressive, metastatic, terminal prostate cancer (PC).

Because of widespread metastasis, surgery and/or radiation were no longer options. The only hope was to slow the rampage and buy time. The doctor purposely did not speculate how much time. But after the call, Seals Googled estimates while still at work: a year if lucky, more likely six months.

Seals had just turned 42, young for any PC diagnosis let alone advanced, metastatic disease. In a daze, he finished his shift as a pipefitter at a pulp company near Mt. St. Helens. Driving home through rural Washington, he pulled off on a dirt road and parked at an overlook of the valley below. A few tears soon gave way to wrenching sobs. It all seemed so ironic, so unfair. After two bitter divorces, a descent into meth addiction, and a failed suicide attempt that past summer, he’d just managed to turn his life around.

And now terminal cancer? “I just felt so…gypped,” Seals says.

At the time of the attempted suicide, Seals was living in a garage, his credit rating in the 300s, $12,000 in unpaid traffic violations, another $20,000 owed to the IRS. Most all his earthly possessions had been stolen or sold for drugs. The only things of value left: a life insurance policy, his blue collar job from which he’d already been suspended once, and a beater to drive to work.

Seals was en route to his job on August 5th, 2006 when he stopped for gas. After filling the tank, he realized he’d left his wallet at home 45 minutes away. He begged the cashier to let him pay later. She said no. By the time a friend brought money, Seals knew he had no chance of getting to work on time. He knew he would be fired.

The solution came as he approached a sharp bend in the highway. The insurance policy was in his kids’ names. He’d make it look like an accident and at least give them something. Flooring the accelerator and with his seat belt unbuckled, he prepared to slam into the embankment. That’s when he saw an elderly couple paused on the shoulder. “As high and devastated as I was,” says Seals, “I knew I couldn’t take out others with me.” He yanked the emergency brake and steered as hard as he could to avoid hitting their car. The nose of his vehicle barely clipped theirs, but it was enough to send him spinning into a boulder, which, in turn, flipped it over and down the embankment.

The car was a wreck. Miraculously, Seals wasn’t, his only injury a raspberry on his forehead. He crawled upside down through a smashed window, took an 8-ball of meth from his pocket, and buried it. When the state trooper arrived, Seals broke down, certain he would go to prison. With unexpected kindness, the trooper offered him his cell phone and suggested calling his boss. A different supervisor answered. The boss out to fire him, miraculously, had taken the day off. The supervisor advised Seals to take some sick leave and return next week. The trooper wrote Seals a ticket for reckless driving.

It was at this point the old man said, “Young man, can I talk to you?”

He explained he and his wife were driving to an Narcotics Anonymous meeting when the crash occurred. “This is no way to live,” the old guy said, clearly recognizing a fellow addict. Between the old man’s counsel and a sense that fate had offered him one last chance, Seals resolved to quit meth cold turkey. He has not used since.

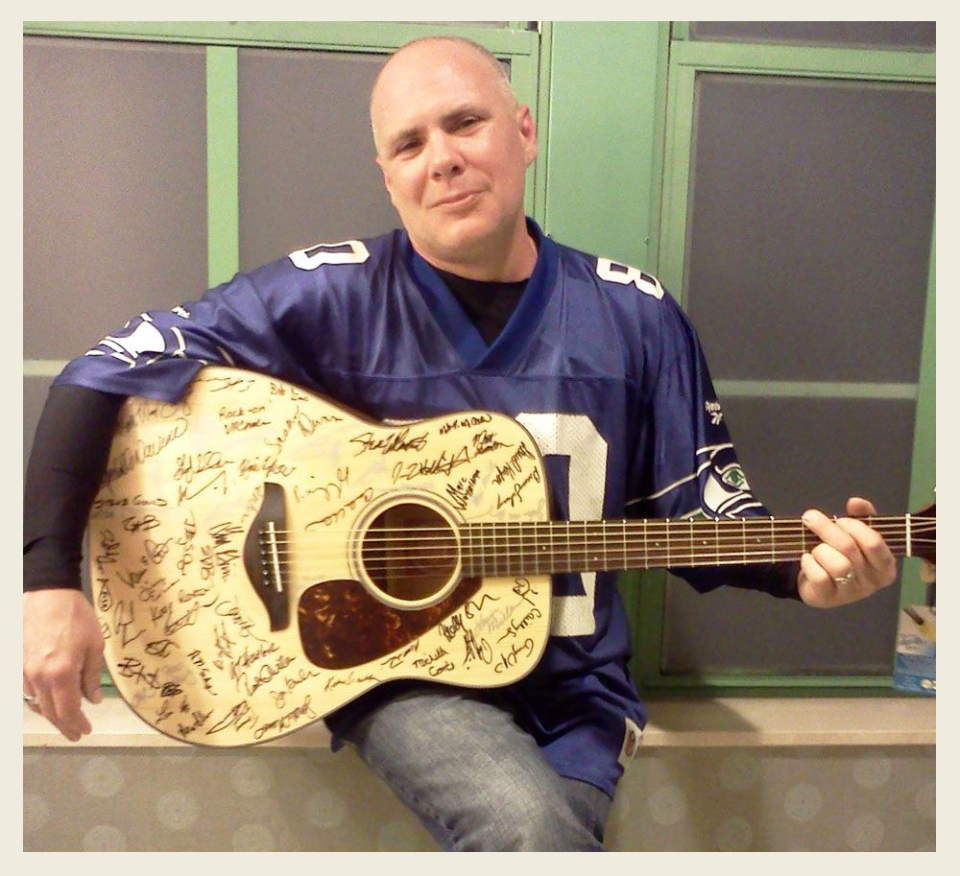

Five months of sobriety later, the worst of his withdrawal over, Seals was playing music at a local tavern when he laid eyes of Mandy, a 27-year-old woman destined to become the love of his life. For the few blissful months before his diagnosis, the two enjoyed a kind of passion neither had ever experienced.

That dark night of his diagnosis, perched on the edge of the forest, Seals sobbed for this loss and all the others he knew his cancer would soon bring them both-intimacy, yes, but the chance to grow old together, too. Finally, after an hour of crying and cursing God, Seals composed himself, the catharsis complete.

Just then, a black bear wandered up the hillside, sat down 20 feet away from him, and stared at Seals. “I’ve hunted and fished these woods all my life,” says Seals, “and I’ve seen all kinds of wildlife over the years. I’d always wanted to see a bear but had never once seen one.” It felt like a sign: cancer notwithstanding, there was so much more he yet hoped to see and do in his life. He realized he wasn’t ready to give up.

“They say people faced with death have two chances: pick up gloves or pick up a shovel,” Seals says. “I’ve always been a fighter.”

The next day he began treatment. “My doctor gave me two options: Castration or Androgen Deprivation Therapy, otherwise known as hormone therapy.” He opted for the latter.

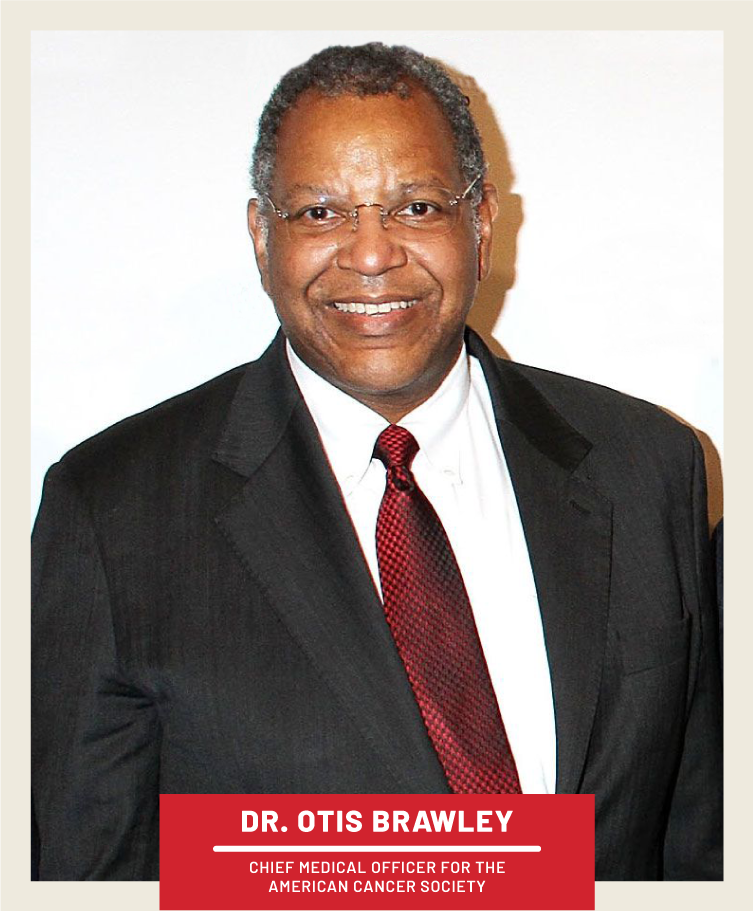

Prostate cancer is not one disease but two, says Otis Brawley, M.D., , Chief Medical Officer for the American Cancer Society. Most guys who live long enough will get the first, low-grade variety doctors call indolent. The reason: It grows so slowly it rarely causes symptoms in a man’s natural lifetime. The good news, says Dr. Brawley, is that up to 90 percent of PC starts off as indolent and for the most part stays this way.

For an unlucky 10 percent, however, PC isn’t content to remain a harmless, lumbering turtle confined to its prostatic box. Some tumors morph into tigers capable of clawing free of the gland and running wild throughout the body. If not brought to heel, this highly aggressive metastatic cancer eventually penetrates bones and other organs, causing an excruciating death.

Medicine is not without potent weapons to fight back. In 1941, Charles Huggins, M.D., a prostate cancer researcher at the University of Chicago, first discovered the role hormones play in fueling PC. In work that would later earn him the Nobel Prize, Huggins showed that shutting down testosterone production in PC patients caused a dramatic reduction in their tumors, bone pain, and other symptoms-at least for a while. On the other hand, restoring testosterone levels in such patients caused their cancer to quickly return. His conclusion: male hormones are the accelerant that feeds PC’s fire.

Castration, either actual or chemical, is not without major side effects-from loss of muscle mass to brain fog to the disappearance of libido. Even so, if quashing our favorite hormone can spare a man a painful death, why is PC not effectively cured by this intervention alone?

The problem, explains Dr. Brawley, is that shutting down the testes only works temporarily, with the time till patients become “castration-resistant” varying greatly between individuals. “I’ve seen men who start ADT at age 60 still alive in their 80s,” he says. “But I’ve also seen men who are dead in a month.”

The reason, he explains, is tumor cells eventually adapt to a low testosterone environment. They become hypersensitive to whatever small amount of androgens still remain in circulation and siphon these out of the bloodstream with great efficiency.

One countermeasure to this enhanced intake are the “mide” drugs: flutamide, nilutamide, bicalutamide, and more recently enzalutamide and apalutamide. Think of androgen receptors on tumor cells as locks that can only be opened by a testosterone key, says Dr. Brawley. The mides look enough like testosterone to fitthese locks, but what they can’t do is actually open them. By jamming as many fake keys as possible into androgen-receptive locks, many PC patients will live a little longer.

But, says Dr. Brawley, PC cells eventually learn how to convert fake keys into ones that actually work. Once this happens, the mide drugs no longer retard PC-they expedite it.

Enter yet a third counter strategy: adrenal gland blockers. This class of drugs was discovered serendipitously after doctors noticed that some men prescribed the anti-fungal drug, ketoconazole, developed enlarged breasts, AKA, gynecomastia. Subsequent research revealed why: ketoconazole prevents the adrenal glands from converting estrogen to testosterone. As miniscule as this source of testosterone is, it’s enough to sustain PC cells that have become hypersensitive.

In 2012, the FDA approved a new, even more potent adrenal gland blocker: abiraterone (tradename Zytiga). Some doctors believe that this not only shuts down testosterone from the adrenals but may also kibbosh even tinier amounts that tumor cells themselves may be producing. Abiraterone has proven a major advance for select patients, though again, it’s a temporary fix, not a cure for this relentless disease.

Dr. Brawley likens aggressive PC to an infestation of roaches. The first roach spray you use kills the vast majority of the pests. Alas, a few stalwart specimens prove immune to Spray No. 1, and their numbers soon begin rebounding. Switching to Spray No. 2 can decimate the ranks of these hardier specimens, but, again, it won’t kill them all. Spray No. 3 just repeats the cycle: killing most but leaving a handful of super-survivors that will eventually not only tolerate all pesticides but actually learn to feed off them.

“It’s Darwinian,” says Dr. Brawley. “Survival of the fittest cancer cells.”

Predicting how long different PC patients tale to become “castration resistant” is almost impossible. But by virtually all measures, Todd Seals was one of the truly lucky ones.

The day after his bear sighting, he returned to the doctor’s office to begin ADT. It was here, he recalls, that “Nurse Ratched” first stuck a hypodermic syringe “the size of a turkey baster” deep into his hip muscle, pumping this full of Lupron in paste form. In the years since, Seals says, he’s gotten used to regular Lupron shots. But that first one, he says, was like a baptism by fire.

The nurse also handed him Rx for bicalutamide (tradename Casodex) to take daily. Within a month, his PSA score had begun dropping; within a year, he officially joined the “Zero Club”-that fraternity of fortunate patients whose PSA levels have become undetectable, a sign their disease is, for now, in remission. Even better, his symptoms disappeared: no more cough, back pain, or pissing blood. Even his prostate-so grotesquely swollen when a needle biopsy confirmed the stage 4 cancer diagnosis-had shrunk to near normal size.

But not everything was copasetic. The drugs had pronounced side effects: fatigue, brain fog, loss of muscle mass, breast development. Worst of all: his libido vanished entirely. “It wasn’t actually that bad for me,” Seals recalls. “I didn’t think about let alone crave sex at all-I was like a castrated dog.” The impact on Mandy was a different story. With the help of Viagra and later an injectable erection drug called Trimix, the two could still make love. But both knew it was not, and would never be, the same.

“As hugely in love as we were,” says Seals, “I told Mandy that she hadn’t signed up for this.” Maybe, he offered, the two should stay friends, and she could find another guy with whom to live a normal life. “But,” he says, “she refused to hear any of it.”

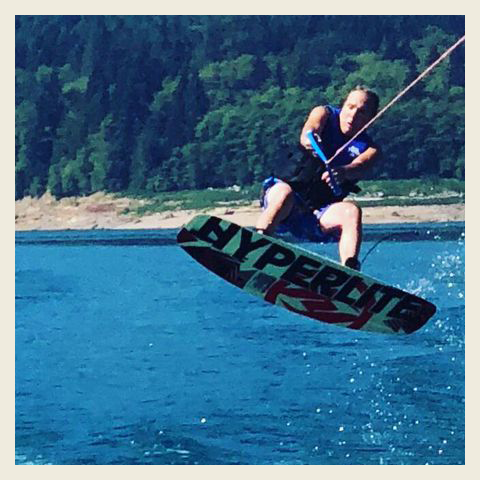

Instead, Mandy became his savior, determined to buoy his spirits and help him fight. When he was exhausted and lacking motivation, she forced him off the couch and take a walk. Several months into ADT, the two went swimming under a bridge on the Tootle River. As a teen, Todd had driven across this same bridge at the exact moment Mt. St. Helen’s erupted. Volcanic heat would eventually turn the water so hot that chinook salmon leapt to the river banks to avoid boiling.

The bridge hung 60 feet over the river. In his younger years, Seals’ friends would jump off it but he’d been too scared. That day, as Mandy watched, he finally took the leap. “The first thing I learned,” he jokes, “is to never jump 60 feet into water and land on your butt with a swollen prostate.” Pain notwithstanding, what he felt most felt was exhilaration. “I realized in that moment, I’d never again let fear hold me back. Mandy felt it, too-that this was the start of something, that we would not waste our lives in fear.” Later that year, when the two married, Seals was so happy that he promised her 30 years together.

But 18 months into ADT, Seals’ PSA started creeping up, a sign that for all his optimism, his cancer was on the move. Suspecting the Casodex’s “fake key” had begun opening the lock it was supposed to just jam, his doctor took Seals off the drug. To their great relief, Seals’ PSA plummeted back to the Zero Club. By the four year mark, his doctor recommended Seals try a break from the Lupron, too.

His PSA went up, but only slightly, before plateauing at a modest level. He and Mandy were thrilled with the total ADT drug holiday and the return of all the benefits testosterone has to offer-from muscle tone and mental acuity, to renewed energy and libido. They prayed it would last but knew it couldn’t.

When his PSA resumed its ascent--slow at first, but with increasing velocity-the doctor put him on a different hormone, DES, similar to Lupron. Briefly, this beat the PSA down, but it soon pooped out. Seals went back on Lupron, and for a short while, his doctor tried Casodex again, which sometimes works after a prolonged break. But the spell was broken. With 25 years of his promise to Mandy remaining, Seals’ PSA began doubling every six weeks. He was, officially, “castration resistant.”

Seals' doctor outlined other options he could try. These included chemotherapy, the adrenal gland blocker Zytiga, and a cancer vaccine called sipuleucel-T, tradename Provenge. With its huge price tag and debatable efficacy, Provenge was a controversial choice. The first FDA approved vaccine for PC, it was to educate and empower a patient’s own immune system to find and more effectively fight cancer. In clinical trials, Provenge extended life an average of 4.1 months. But for a select few, it worked much better, with some still in remission years after the trial began.

Both of the Seals were convinced he’d prove one of these select few, and they rejoiced when his health insurer approved the treatment. Soon afterwards, however, a new research study concluded that patients in Seals’ condition would not benefit-in fact, Provenge might make his cancer worse. The insurance company rescinded their approval.

The number one followed by 19 zeros: this is how many pathogens and assorted other biochemical villains the “beat cops” of your immune system learn to recognize by age 15. With each passing year, they learn to recognize many more. Just as importantly, they also learn who the good guys are and leave our own cells alone.

Distinguishing between alien invaders and ourselves, to be sure, is an incredibly complex job with life-and-death stakes. If policing is too lax, the bad guys can easily overrun us. But too hair-trigger a response risks killing us by friendly fire, the hallmark of autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis and lupus.

Cancer cells, for the most part, pose a particular challenge for the immune system, in part because they arise within our own cells, in the process co-opting natural self-repair mechanisms we need to heal.

Imagine, for instance, you’ve cut yourself shaving. Very quickly, your immune system rallies a host of inflammatory agents to clear out the damage and rebuild healthy tissue. Once the debris is cleared, stem cells replicate quickly to replace what’s been lost. But when healing is complete, this reproduction rate automatically returns to normal.

Controlling how fast or slow cells reproduce, not surprisingly, are specialized genes-in particular, oncogenes that serve as accelerators for faster replication, and tumor suppression genes that apply the brakes when it’s time to settle back to routine maintenance mode.

But what happens if the accelerator gets stuck in the on position, or the brakes fail to engage? In a word, cancer: a natural healing process gone awry.

“Each day,” explains Dr. Brawley, “we have billions of cells undergoing duplication in their DNA. And just as you sometimes get corruption when copying files on your computer, the exact same thing can happen to DNA-things don’t get copied exactly right. We call this a mutation.”

Most mutations are no big deal, reassuring given that we experience thousands of them daily. But when mutations occur in oncogenes or tumor suppression genes, it can lay groundwork for their owner cells going rogue.

This happens more often than you might think. “Every day by age 40,” says Dr. Brawley, “the average person has between 4-8 cancer cells arising somewhere within their body that are starting to go haywire because of this ‘corrupt file’ thing.”

So why aren’t we all keeling over? Fortunately, our bodies have evolved numerous ways to shut down small cancers before they do any harm. This starts, says Dr. Brawley, with specialized DNA repair enzymes that recognize harmful mutations and attempt to excise them. Unfortunately for some individuals, certain DNA mutations like the famous BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes linked to both breast and prostate cancer, prevent the production of these enzymes, causing their risk to soar.

A second mechanism, apoptosis, is a built-in suicide instruction set that programs our aberrant cells to recognize they’ve turned into zombies and kill themselves. Most, though not all, comply.

If both strategies fail, our immune system kicks in, specifically potent killers called T cells capable of recognizing and eliminating up to 100,000 cancer cells each.

Unfortunately, as adept as T cells are, they’re not perfect. Sometimes, for instance, they’re just outgunned-some cancers reproduce faster than the immune system can eliminate them. Other times, cancer cells are able to disguise themselves as normal. T cells may suspect villainy but lack enough evidence to start shooting. Yet another scenario: T cells recognize the villain, gather for an attack, but upon gaining access to the cancer cell’s interior, are ordered to “stand down.”

In recent years, oncologists have learned this stand-down order comes from another natural cellular mechanism dubbed a checkpoint, which normal cells use to prevent autoimmune attacks. But cancer cells can co-opt this same mechanism: Good news for them, bad news for us.

One of the most exciting cancer developments in recent years was the discovery of drugs that can inhibit this checkpoint and allow T cells to do their job.

Ipilimumab (tradename Yervoy) was FDA-approved in 2011 for the treatment of melanoma. “When T-cells enter a melanoma cell,” explains Dr. Brawely, “the tumor begins flashing a ‘Friend, Friend, Friend!’ signal to avoid being attacked. What Yervoy does, in essence, is call bullshit.” Yervoy’s success helped launch a frenzy of research into other immunotherapy agents-i.e., ways to empower our own bodies to recognize and conquer cancers out to kill us.

Unlike chemotherapy, which is toxic to all cells but more toxic to cancer cells, immunotherapy is designed to target and kill only those cells that need killing, thus eliminating widespread collateral damage. Not only are the side effects markedly less, but most patients prefer the idea that their own bodies-not some poison-is working to heal them.

Since Ipilimumab’s discovery, two related drugs- pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo)--have also been approved to take the brakes off the brakes that tumor cells hope to apply. For some cancers-melanoma, lung, and kidney-these drugs are making a huge difference for select patients. Case-in-point: Ex-President Jimmy Carter. Fiagnosed with melanoma in the summer of 2105, the disease had already spread to his brain and liver. After surgery and radiation, he was treated with Keytruda, and by that December, he announced at his weekly Bible class that MRIs could no longer find any trace of cancer in his brain.

The popular media, not surprisingly, was quick to bandy about the c word: cure. Researchers are more circumspect, taking pains to distinguish cure from remission. Nor do these drugs work for all cancers and all patients. They appear to be most beneficial for cancers with high mutations rates within tumor cells. Immunotherapy researcher James L. Gulley, M.D., Ph.D., Chief of the National Cancer Institute’s Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, suspects that the more mutations, the more chances T cells have to recognize targets.

Most prostate cancers, unfortunately, have moderate mutation rates and checkpoint inhibitors don’t seem to help. Researchers like Dr. Gulley believe the problem may be a failure of T-cells to recognize tumors cells in the first place. He and his colleagues are working to develop PC vaccines that might help them do this.

As promising as PC vaccines are in theory, to date only one has made it through clinical trials to receive FDA approval: sipuleucel-T, i.e., Provenge. Treatment with Provenge is complicated. Over 2-3 hours, a patient’s white blood cells are collected then Fedexed to a laboratory for a proprietary process that teaches them to recognize a specific PC target. Once educated, a second proprietary process stimulates them into maturing and replicating, in the process generating an army of smart warriors. These are then Fedexed back to the doctor’s office for reinfusion into the patient within two or three days. Each cycle costs $35,000, and patients must undergo three cycles in three weeks.

In granting approval, the FDA noted that Provenge extended life in most PC patients by only 4.1 months. “But if you looked at the guys who were still alive three years after they got Provenge,” says Brawley, “there were twice as many of them as those who didn’t get it. If you’re a good responder to it, Provenge can buy you a long life.”

Only a small percentage of patients, unfortunately, fall into this category. Given the less than spectacular benefits the rest can expect, analysts were quick to question Provenge’s cost effectiveness. Once on the market, doctors quickly discovered a third strike against the vaccine: it didn’t reduce PSA levels, a marker patients and doctors alike have for so long relied on to gauge disease progression. Because of this, says Dr. Brawley, many urologists doubted its efficacy and declined to prescribe it. Dendreon, the company that developed Provenge, eventually declared backruptcy, though they transferred the rights to make Provenge to another company. The result: a potential blockbuster drug that, though still available, itself remains on life support.

During his first five years of remission, Seals closely followed the vicissitudes of Provenge. He had no illusions that hormone treatment alone would keep his killer at bay forever. His goal was to live long enough to benefit from the next life-extending medical advance. Like Tarzan swinging from vine to vine, he hoped to remain airborne long enough to find his next lifeline. Provenge, he was convinced, was his next vine.

After the insurance company denial, Seals appealed their decision and won. He was back on the list for treatment when, several weeks later, his oncologist called with bad news. A new study in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute had, he said, “proven” that Provenge wouldn’t work for him. In fact, the doctor said, it could make his cancer worse. Once again his insurance company denied Seals coverage.

He and Mandy refused to say die. They appealed this second denial all the way to the Washington State Insurance Commission, which ruled insurer had acted on unproven scientific speculation. Seals could, they ruled, receive Provenge after all.

“I cannot fully describe how Mandy and I felt inside upon hearing this wonderful news,” Seals recalls. “We cried tears of elation and relief. It was over.”

This may have been true for the legal wrangling, but not for the cancer itself. Over the months of appeals, Seals’ PSA had climbed from 22 to over 100, and it was now doubling every six weeks. He could feel his symptoms, as well, returning in full force. In his heart, Seals remained convinced Provenge was his last best shot at survival.

“I received my first Provenge treatment in May of 2012,” he says, “and completed the therapy June 1.” Within hours of the final infusion, he bought his wife a boat. “I truly believed we’d have a future to enjoy it.”

Slowly but surely, his symptoms began receding though his PSA score remained disconcertingly high. He asked his doctor to try yet another round of Casodex, the androgen-receptor blocker, hoping it might have a little magic left. It decreased his PSA slightly but not for long. At this point, his doctor prescribed zoledronic acid (tradename Zometa), an osteoporosis drug. Though this doesn’t kill cancer, it significantly hardens bones in PC patients, making it harder for tumor cells to implant and grow.

On December 10, 2012, another new “vine” received FDA approval: abiraterone (tradename Zytiga), the potent adrenal gland testerone blocker. Zytiga is a potent drug and must be given with prednisone, a powerful anti-inflammatory with its own side effects. For Seals, the combination of Lupron, Zytiga, and prednisone left him with nausea, profound fatigue, memory problems, excess bruising, hot flashes, susceptibility to infection, which lead pneumonia. Despite all this, Seals says the benefits far outweighed the drawbacks.

“Within two weeks on Zytiga, my PSA dropped by 75 percent and kept dropping,” he says. By October, 2014, he re-entered the “zero club.” As of June 2018, PSA still remains at undetectable levels, and scans can find no evidence of metastasis.

Most patients are lucky to get two, maybe three years, before Zytiga begins failing. Seals credits Provenge with making all his other medications work that much better. “My primary care doctor even made the bold statement that the combination of Provenge and Zytiga might, in my case, be the magic one-two punch that puts this disease into a permanent remission!”

But as much as wants to believe this, Seals has learned to take nothing for granted.

Almost everything about Todd Seals’ prostate cancer is atypical, from the young age at which it began, to his health 12 years after he was given six months to live. He knows his case inspires many fellow sufferers, the vast majority of whom he also know won’t fare nearly as well as he has. He acknowledges the fine line between real and false hope, but believes that the case for the genuine variety grows with each new medical advance.

In this optimism, Seals is not alone. “Our goal, says Gulley, is to take a fatal disease and make it curable much the way the AIDS ‘cocktail’ can drive HIV to undetectable levels. As long as patients stay on the medicines, their disease is functionally cured.”

Seals, for his part, still has in reserve several proven, mainstream treatments, such as chemotherapy drugs, should his current remission end. Docetaxel (Taxotere) and cabazitaxel (Jevtana) are drugs in the taxone family originally discovered in the yew tree. Highly toxic to prostate, breast, lung, and other cancer cells, they work as so-called spindle cell inhibitors. “When a cancer cell is dividing,” explains Brawley, “an internal cage is created to hold the cell up. This cage is made from spindles, and these drugs attack them, causing the cell to collapse and die.”

As effective as taxones can be, like most chemotherapy agents, they also can cause severe acute and long-term side effects, from joint pain and allergic responses, to fluid accumulation in the lungs. They must be administered in conjunction with prednisone. Though glad the option remains available, Seals hopes he’ll never need to go down the chemotherapy route. Thanks to new treatments that have come on line since his original diagnosis, he may not need to.

Two of these are in the “ide” family-enzalutamide (Xtandi), first FDA approved in 2012 and apalutamide (Erleada) just approved Feb. 14, 2018. Like the Casodex that ultimately stopped working, these are in the fake key category that prevent androgens from opening androgen receptors. But unlike Casodex, these newer drugs a much higher “binding coefficient.” As Dr. Brawley explains, “this means they are much less likely to fall out of the keyhole.”

Arguably even more promising is the potential for new immunotherapies. At the NCI, for instance, Dr. Gulley and his colleagues are testing a wide range of possibilities. One such study is looking at the combining a PC vaccine with a checkpoint inhibitor-a synergistic approach that’s already shown, in a small pilot study, effectiveness at lowering PSA and shrinking tumors in half of advanced patients.

Another immunological attack under investigation an innovative way of “weaponizing” a patient’s T-cells by genetically adding a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) on their surface. The resulting CAR-T cells are then reinfused back into the patient’s body, turbocharged to hunt and kill PC cells.

Still another strategy is attempting to exploit a natural protein called PARP1, whose job it is to repair nicks in single strands of DNA. Drugs under development called PARP inhibitors block the repairman’s efforts. Thus when the tumor cell attempts to reproduce, it leads to multiple double stranded breaks. Patients whose cancer is linked to BRCA or similar genes lack the enzyme needed to repair these breaks. The result: the rumor cells can’t replicate.

As wily and intractable an opponent as prostate cancer has long been, Gulley is optimistic its days are be numbered. “We’re already starting to see combined immunotherapy agents leading to meaningful clinical responses. I absolutely believe it’s possible that even newer treatments over the next five years will take patients with incurable disease and render them curable.”

It’s a sentiment that Todd Seals frequently echoes, too, albeit from a different perspective. “Each passing year brings me closer to keeping my 30 year promise to Mandy,” he says. “Each year, new medications are being tested and approved for PC treatment. The future is bright and getting brighter every day. It makes me wish I had promised Mandy 40 years. I have an amazing, wonderful life and I am going be here for a long, long time.”

Here’s hoping cases like his will soon become more rule than exception.

('You Might Also Like',)