In life, Claude-Philippe Berger styled himself the “traditional king of Tanna”, an island of 30,000 people in Vanuatu. Berger, who was born in 1953 in Casablanca and claimed to have once been a diplomat, first visited the islands in 2011, in hope of veneration. What he found was a South Pacific of the imagination: champagne-coloured beaches, rose sunsets, the rumble of volcanoes. Yet Vanuatu is also threatened by a rising tide, and cyclones regularly hit its scarce infrastructure and fragile agrarian economy.

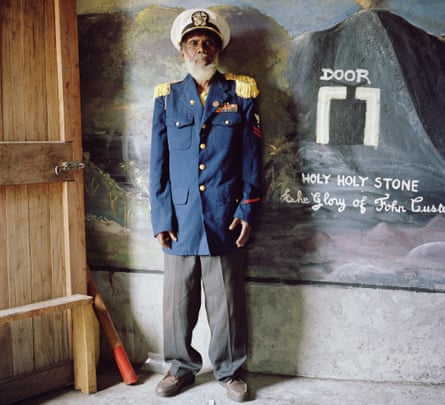

Later, living in Nice as a supposed king in exile, Berger adopted the studied lifestyle of an obscure European royal: swathed in a blue sash and medals, he could be found cutting ribbons at provincial art exhibitions, or hosting boozy soirees in San Remo, where he and his “royal house” would engage in energetic lobbying of Ni-Vanuatu politicians to have his island throne restored.

When Berger died in July, there was little pomp for him in France. But, according to one “royal” insider, 300 people in Vanuatu walked across the bush “in heavy rain” to pay their respects. As with so much about the late “king”, reports of his memorial may be an exaggeration.

Men like Berger come to the archipelago in pursuit of an old prophecy. In Vanuatu, there are people who say a messiah will one day arrive from a distant land, bringing the islands the prosperity they were denied by their former colonial rulers, Britain and France. In anthropological parlance, such beliefs are often labelled cargo cults – a term fraught with condescension, framing these spiritual movements as religions constructed around the material wealth, the “cargo”, of the western world. Over the past 50 years, though, a steady stream of westerners have acted out such prophecies in the hope of gathering believers. As Ketty Napwatt, a Ni-Vanuatu activist and former politician, told me in 2014: “We have these crackpots showing up all the time.”

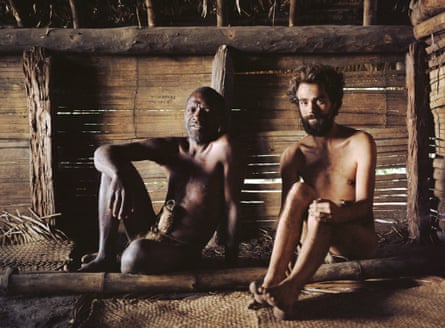

Crackpots they may be. What kept photographer Jon Tonks and me interested, over several trips to the South Pacific and to these men’s homes in Europe and America, is that they have found some success in their dubious quest: there are islanders willing to make a little room in their beliefs for the newcomers.

A few years ago, we saw the flag of Berger’s house reverently unfurled from a thatched leaf hut on Tanna, and the woman who lived there told us she and her family believed not in the modern nation of Vanuatu but in a brighter future to come when the prophecy was fulfilled.

The fantasy of being revered by people on the far side of the world is an old one. Early European explorers such as Captain Cook were supposedly received as divine beings by the local people whose lives they would upend. The dream endured from Robinson Crusoe to colonial fiction such as Kipling’s white rajahs in the Kafiristan of The Man Who Would be King – a deeply rooted idea of the west’s divine right to rule.

We happened across our modern-day prophets by accident. Tonks and I had gone to Vanuatu in 2014 because we’d read about villages there where the locals believe God is an American soldier.

Every February, men in Vanuatu carve muskets out of bamboo, don military fatigues and march through the streets saluting the US flag. This ritual, they believe, will entice back to the island a man whose prophesied return sits at the centre of a complex belief system that was, perhaps ironically, forged in opposition to oppressive foreign rule.

Prior to independence in 1980, Vanuatu was called the New Hebrides, an incongruous name thrust on these 83 tropical islands by Captain Cook. At the turn of the 20th century, it was a colonial oddity: jointly ruled by Britain and France in a mess of competing systems. With the colonials came legions of missionaries. Sectarianism and strict religious law tore through traditional societies. Crucially, a local drink called kava, which numbs the throat and soothes intertribal disputes, was banned as a heathen brew.

“Man Tanna [a collective name for the islanders] was not ready to let go of everything the white missionaries did not like,” Napwatt told us, and in the 1930s a spiritual movement took root in response. Islanders claimed to have encountered a mysterious man on Green Point beach. They said he called himself John Broom, and one day would return from a distant land to sweep the white men off these islands. He would come bearing cargo, the riches being siphoned off by the colonial powers. The old ways would be restored, with kava-drinking protected. It would be a cataclysm, a rapture. Mountains would tear open.

Over time, the name of the movement’s central figure softened to John Frum, and its acts of civil disobedience spurred the colonial authorities to lock up a few chiefs. When the US army commandeered the largest island for a base in the second world war, the prophecy became tangled up with ideas of American might. The faithful began planting red crosses in their gardens, like those on army ambulances; since then some have marched under the star-spangled banner once a year in the hope it would entice John Frum back from America.

In Tanna, Tonks and I saw platoons of men marching under the midday sun. We also met Cevin Soling, a documentary-maker from Boston who for years had brought strange cargo – salad spinners, fishing tackle for people who don’t fish, medical equipment – to John Frum believers in Sulphur Bay.

“Apparently there was a prophecy I would come,” said Soling, wearing white chinos and a baseball cap. Indeed, in a speech to believers, the chief of Sulphur Bay described him as the “last man” who would reveal the destination of their movement. Soling had tried to turn the whole endeavour into a documentary, and even made necklaces with his own face printed on them.

Outsiders might think Ni-Vanuatu are gullible people, easily taken in by foreign soothsayers. But that’s not the whole picture. There’s a scene in Soling’s film where one of the John Frum chiefs is examining the goods the foreigner has brought, pleased the cult appears to be working – it just so happens the cargo has been brought by a wealthy American film-maker, not Frum. In our conversations with the chief, he evaded the question of whether Soling was the man they’d been waiting for.

“People tend to forget there is a huge amount of local politics on these islands,” says Kirk Huffman, who worked as an anthropologist for the post-independence government in Vanuatu and was curator of its national museum. “One level of analysis is that these chiefs are using outsiders for their own benefit.” Many communities believe the Frum prophecy and the arrival of a man like Soling, weighted down with offerings, can bolster a tribe’s standing. “Something similar happened in Fiji in the early 19th century, with white people being asked by traditional chiefs to become their allies. These local leaders would use the outsiders, not least their arms and ammunition, to political ends,” Huffman says.

Many get dismissed, among them a young dreamer from Norway we met, who had turned up at a village in Tanna where local people believed Prince Philip was the reincarnated god of a nearby mountain. These beliefs have endured since the 60s and, since his death, it has been suggested the mantle might be passed to Prince Charles. The Norwegian learned of the prophecy online, and burned his clothes and passport on arrival, intending never to leave (he eventually did, after a row with the chiefs).

We also saw the scars wrought by Las Vegas property developers who, on the eve of independence in 1980, planned to create their own libertarian microstate, forging a cult reminiscent of Frum around local leader Jimmy Stevens. Stevens spent the rest of his life in prison, and his son was killed by soldiers sent to put down the rebellion. The libertarians, meanwhile, sloped off into the sunset.

These stories led us to Berger who, in a white tunic pulled taut by too many medals, would bask in the attention of Tonks’s lens. He claimed to have been handed his title in 1999 by a Corsican gun-maker who had led an armed insurgency of islanders in the 70s, hoping to carve Tanna out from the rest of the archipelago and become a “traditional king” of this new country. He was eventually arrested and deported in 1974.

If that sounds like something from Joseph Conrad, Berger was more Walter Mitty than Colonel Kurtz. His royal retinue in Europe comprised ageing white counts and countesses who took it all rather seriously. A few years ago, we attended their annual gala in a stuffy hotel in Berlin. “You may address the king only as ‘Majesty’,” one doughy-faced German count said, as he tied on a black cloak adorned with Templar-looking crosses.

There were rounds of liturgical singing led by a priest, standing solemnly next to the tea-making facilities. The king knighted his counts with a ceremonial sword in recognition of obscure services to the crown (one way to curry favour was to provide Berger with air miles). At one point an oversized cheque for €600 was held aloft, intended for the Ni-Vanuatu faithful after Cyclone Pam had ripped through their villages that year.

Berger said with all sincerity that Tanna should be an independent country, with him as king. “It’s not just me,” he told us. “The people, they want this.” Then there was dancing in the hotel ballroom, after a plinky rendition of God Save the King on a Casio keyboard.

In 2016, we joined Berger on a “royal visit” to Vanuatu and learned he’d made all sorts of promises – about bringing development and investment, and new roads that would be carved through the bush. His right-hand man there, Tom Kuai, administered the donations sent by the royal house, including water tanks and solar lamps. He admitted they were still waiting for the pledges to be fulfilled, and when asked how far Berger was recognised as a king, Kuai became oblique: “We know we have a traditional king in exile,” he said.

On our visit, we met a group of men from Tanna who had moved to the capital, Port Vila, looking for work. They explained that families back home had listened to Berger when he showed up pledging support, but frustration was growing, especially when they got wind of the lavish balls happening in Berger’s name back in Europe. One of the group stared hard at Tonks’s portrait of Berger in his cream-coloured finery in Berlin and asked: “Does it make this man rich to say he’s the king?”

As far as we could tell, Berger did not make a fortune from his links to Tanna. Those showing up with claims on the prophecy are lucky to be given a patch of unruly land, which they usually have no idea what to do with.

So what motivates these men who would be king? Most believe their adventures are philanthropic, a bid to help a beleaguered people. In part it goes back to those old explorers whose “discoveries” were valorised with tales of the godlike status they attained. In distant Vanuatu, with its economic disparities and oral tradition of storytelling, these men find a place to reinvent themselves. Or, as Huffman says, simply somewhere people will listen to them: “There’s something very special about Tanna in that there is a deep cultural longing for contacts outside of the island, and those roads can go as far as the other side of the world. The John Frum movement is only a minuscule part of that history.”

Despite two centuries of missionary activity, many traditional beliefs remain deeply ingrained. The old ways have not been entirely abandoned and John Frum is only one modern expression of that. As outsiders, “we are only a temporary blip on the screen of Tannese reality,” Huffman says. In the end, who are the real “cargo cultists” here? Is it those in Vanuatu, waiting for the return of their divine man to erase the trauma of the colonial past? Or the counts and countesses who raised their glasses in the hope that Berger was a real king?