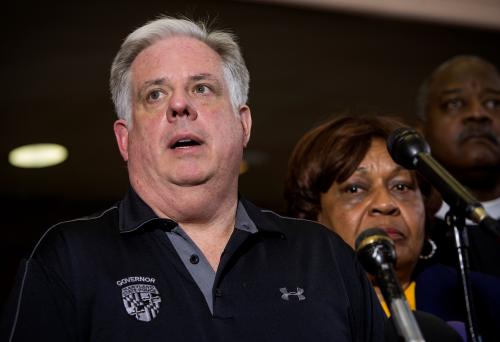

The education policy community is accustomed to debates about what schools should teach, how they should teach it, and who should do the teaching. When Maryland Governor Larry Hogan signed an executive order requiring public schools to open after Labor Day, it stirred debate on a less familiar question: When should we teach students?

Few aspects of public schooling have implications as wide and varied as the calendar. The calendar affects students, parents, staff, and the broader public, in ways as different as rush hour traffic and summer nutrition for students in poverty. Here, I examine the three basic variables that define the calendar—start and end dates, off time during the year, and start and end times—and what types of effects might come from tinkering with those variables. The objective is not to argue whether a post-Labor Day start date is inherently good or bad. In fact, I suspect it is neither. Rather, it is to illustrate that the interests related to school calendars are so intertwined that a change to one part of the calendar is likely to yield an assortment of indirect effects.

Start and end dates of the school year

Hogan’s executive order called for school to begin after Labor Day and end by June 15 (with waivers possible for districts with compelling reasons). In making a case to the public, he emphasized the potential economic benefits from giving families more time during the summer to visit tourist attractions within the state. The governor has touted a 2013 report by Maryland’s Bureau of Revenue Estimates that claims—albeit with little detail—that the net effect of a post-Labor Day start date would be $74.3 million in direct economic activity and another $7.7 million in local and state revenue.

Hogan’s critics have argued that he seems unduly concerned about the impacts of school calendars on state tourism revenue. A seemingly more fundamental concern is about the effects on students. Here, the effects look less rosy, especially for students in poverty. Kids forget things over the summer, and this is particularly true for kids with little access to out-of-school academic resources, which could exacerbate achievement gaps. (Of note, some research disputes that there is much difference in learning between year-round and nine-month schooling.) Extended summers also create other challenges for low-income families, like a long stretch without access to relatively healthy (and subsidized) school lunches.

Further harm to student learning seems likely if compressing the calendar results in fewer instructional hours. Hogan has argued that this executive order will change when instruction happens, not reduce the overall amount of instructional time, although it will constrain districts’ abilities to exceed the state’s minimum hours requirement. To preserve the same number of hours while pushing back the start date, something else in the calendar has to give.

Time off during the school year

One way to make up for lost time in the summer is to reduce the number of non-instructional days during the year. Any school calendar is dotted with off days for students with time reserved for holidays, vacations, and staff development, in addition to a cushion left for weather-related cancellations.

Reducing the number of non-holiday vacation days, like spring break, might seem like low-hanging fruit to reclaim lost time. However, there are tradeoffs involved. Some districts use slack in their within-year vacation time to give days off to observe holidays widely celebrated in their communities (e.g., Chinese New Year or Yom Kippur). Moreover, if there is economic gain from extending families’ opportunities for in-state tourism in summer, it stands to reason that there is economic loss from reducing the number of short breaks and three-day weekends within the school year. On the other hand, mid-year off days can create challenges for working parents, many of whom would appreciate having fewer days during the school year without child care.

Another way to retrieve lost days is to cut back on staff professional development time. Several studies have examined the effects of teacher PD programs on student learning, with findings generally ranging from no benefit (perhaps the most common finding) to potentially large benefits from high-quality programs. These programs can be expensive, so funds saved from reductions in PD time could be repurposed elsewhere to help students more directly.

Start and end times of the school day

Finally, we could think about adding more time to school days to make up for the later academic start. Most teenagers don’t like to wake up early, and they have a good excuse. Changes to the body’s circadian rhythms in adolescence mean that waking up a teenager at 7 a.m. is the rough equivalent of waking up an adult at 4 a.m. And these early wake-ups seem to have effects, with later start times tending to yield substantially better academic and health outcomes for adolescents. This led Brian Jacob and Jonah Rockoff to urge districts to consider staggered start times with elementary schools opening first.

For districts, start and end times can create daunting puzzles, especially with respect to busing. By staggering start and end times and using the same bus for multiple routes and schools, districts can reduce costs and the time that students spend on buses. All else equal, shorter school days create greater flexibility for administrators to stagger start and end times without putting any schools in session outrageously early or late (or requiring the purchase of more buses that are used only lightly). Staggered start times might also mitigate the effects of school drop-off on rush hour traffic.

For employed parents, school start and end times have implications for job schedules and child care decisions. Typical school dismissal times of 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. can leave coverage gaps of 15-25 hours per week for employed parents, and extended care is often expensive ($630/month at my own kindergartener’s Maryland public school). These demands can be particularly challenging for low-income parents with little work schedule flexibility and disposable income. Here, too, staggered start times that begin with elementary schools might help, mitigating the need for before-school care for young children who are most likely to need their parents’ help in getting to school.

Conclusion

So what can we make of this, and what can we make of Hogan’s decision to postpone the first day of school until after Labor Day? Perhaps the clearest takeaway is that the decisions, interests, and effects related to school calendars are interconnected. One change to the calendar necessitates another change in response, and those changes are likely to produce a variety of effects.

A second, and related, takeaway is that tradeoffs in scheduling are inevitable. A change that positively affects one group might adversely affect another. Earlier start times might help mom and dad get to work but leave children sleepy as they move through the school day. More vacation days within the school year might increase tourism-related tax revenue but strain parents with inflexible job schedules. Navigating the set of scheduling questions requires an exercise in choosing which interests, and whose interests, to prioritize. To many critics of the Labor Day executive order, Governor Hogan’s biggest mistake was choosing the wrong group’s interests to prioritize.

Commentary

School calendars and Maryland’s Labor Day mess

September 19, 2016