EDUCATION: SPECIAL REPORT

A Tale of two Schools: Tears, fears and some light in the darkness

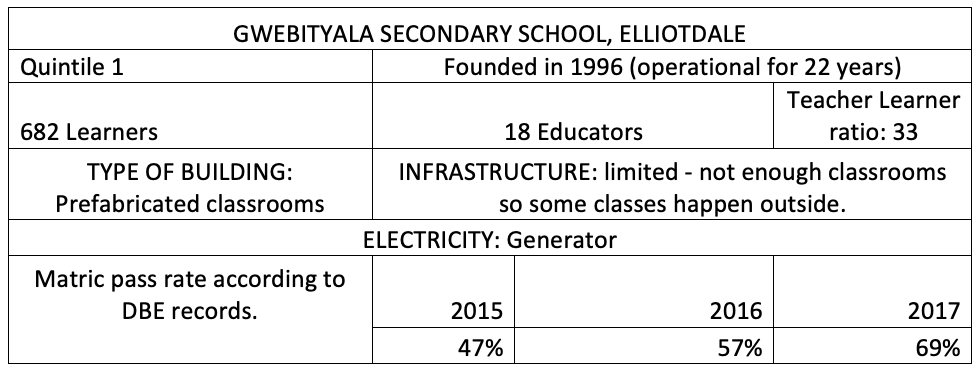

In the rural Eastern Cape, about 100km and an hour-and-a-half’s drive apart, are two schools, both categorised below quintile three on the school categorisation system, which means they are located in extremely poor communities and learners do not have to pay school fees. Based on the matric pass rate alone, one of these schools is achieving fairly good learner outcomes, which are steadily improving each year; the other is technically failing. Journalist Ziyanda Zweni spent a week at each school, staying with an educator from each school for the week. Her mission was to observe and share what it’s like on a day-to-day basis in schools operating under difficult circumstances – especially as a teacher.

At one school she found a principal who is inspiring the teachers, learners and broader community to make lemonade out of lemons; at the other, a space that remains haunted by shadows of poor practices from the past – where the new principal and teachers are fighting a daily battle to turn the ship around.

Welcome to Gwebityala Senior Secondary School in Elliotdale and LM Malgas Secondary School in Willowvale.

Part 1

Gwebityala: Doing a lot with just a little

Schools are usually dark, quiet places after hours. But at Gwebityala Senior Secondary School in Elliotdale’s Khotyana village, lights flicker late into the night. That’s because most pupils don’t go home straight after class: every week night, they gather together by candlelight (a generator occasionally supplies electricity, but it’s temperamental and often doesn’t work) for study groups. For an hour, they read silently; the second hour is dedicated to working together, thrashing out problems and learning from each other.

It’s a reality that makes principal Nohlobo Mjali-Matyholo simultaneously sad and proud. The candlelit sessions are just further evidence of her pupils’ dedication to their studies – and the desperately poor conditions in which they’re trying to learn.

Mahobe Sukiswa, a Grade 12 pupil at Gwebityala Senior Secondary School, in front of the small home she shares with seven family members. Photo: Max Bastard

Mjali-Matyholo has been at the school for 14 years. She started as a Biology teacher (teaching what is today known as Life Sciences) and four years ago she was appointed principal. Every weekday morning, she wakes at 4.50am to make the two-hour drive from her home in Mthatha to work. She uses this time to think about the nine learners who’ve dropped out of school since the start of the year (not bad for a school of 682 learners, but a group she fears might succumb to trouble without school to keep them focused). Mjali-Matyholo also reflects on the numbers that weigh on any South African principal’s mind: her school’s pass rate and what it signifies about the work her school is doing to prepare its learners.

There’s a lot for her to be optimistic about. Reaching out beyond Gwebityala’s gates and into the wider community has borne fruit. At the end of 2014, her first year in charge, 45.6% of the school’s matrics passed – an improvement, the first in years, and one that offered a glimmer of hope. It has been a steady upward climb since then: 56.5% by the end of 2016, and almost 70% for 2017. There was great excitement following the June 2018 exams when only two learners failed out of a class of 177 matrics. So, are they aiming for a 100% pass rate at the end of this year? No, they’re trying to be realistic: 80% is the goal.

Gwebityala Senior Secondary School is hoping to improve its matric pass rate from 69% in 2017 to 80% in 2018. Photo: Max Bastard

Mjali-Matyholo doesn’t believe one single factor has led to this slow but steady turnaround in results – she thinks it’s partly thanks to committed teachers. Also, the pupils are hungry to succeed, as evidenced by those late-night candlelit sessions. The Eastern Cape Department of Education has been a valuable ally. The community around Gwebityala has also embraced the increasingly popular school, rallying around to support its quest for improvement.

A few years ago, the school was in the doldrums. It was the only senior school serving Khotyana and surrounding villages, and its pass rates were dismally low. “In 2014 we asked parents to allow extra classes on Saturdays and for other schools in the area to provide some teachers for the winter and spring camps,” Mjali-Matyholo says. Since then, teachers from neighbouring schools have stepped in regularly to help with extra classes in subjects that Gwebityala usually struggles with. Parents have also become involved: they watch over the learners during study camps; one couple spends every day at the school to provide extra support and adult supervision. The School Governing Body is active and engaged.

Principal Nohlobo Mjali-Matyholo in the office she shares with the deputy-principal at Gwebityala Senior Secondary School, Elliotdale. Photo: Max Bastard

So why are people this willing to pitch in and support the school? Mjali-Matyholo believes it is because most of the adults in Khotyana are unemployed. Many locals didn’t complete matric, which drives a passionate belief in the value of education – one which can be seen at every level, from the cleaners who maintain the school to the teachers, pupils and principal herself. Teachers aren’t shy about asking each other for help; there’s no sense of embarrassment about asking questions or learning from their colleagues. And when teachers aren’t around, pupils keep working: it’s common to see groups huddled together around books.

The school is not without its challenges, though. In an area with few resources and little social support, the school often has to deal with the daily realities of violence, fear and poverty. Pupils who rent rooms close to Gwebityala to avoid the long commute on foot each day are targeted by tsotsis; their small humble living spaces routinely emptied out by thieves. Girls miss school because they can’t afford sanitary pads; sometimes teachers club together to buy such necessities to keep their learners in class.

“We have this competition at school where we award the best performing teachers and have in-house awards for our Grade 12 teachers. Last year I won the best teacher in

my subject. I have a healthy competition going with the Life Sciences teacher who says she can’t be outdone by me while I’m so busy,” she laughs. Photo: Max Bastard

That’s because teachers in South Africa aren’t just teachers; sometimes they have to act as stand-in social workers, too. History teacher Nombuzo Sityodana explains: “We’ve had instances of girl learners confiding in us about the abuse they were experiencing.” The teachers initially tried to help, but found themselves threatened by angry relatives who scolded them for getting involved in “family matters”. So, she continues, “We had to ask for social workers to intervene.”

On occasion, the Department of Education sends in a Learner Support Agent who is trained to talk to young people about their non-academic issues. The agent then reports back to Mjali-Matyholo and her staff so they know who to keep an eye on. The teachers also try to make themselves available for pupils who want to talk about the issues they’re facing at home or in school – although they admit that very few pupils are comfortable confiding in their teachers.

Acknowledging hard work and good performance is a key strategy

keeping learners and teachers motivated at Gwebityala Senior Secondary School. Photo: Max Bastard

Mahobe Sukiswa, a Grade 12 pupil at the school, exemplifies many of the common issues facing Gwebityala’s student body. She shares a home near the school with her mother, father and five siblings. Both parents are unemployed, and the family – like so many others in the area – survives on child grants. She takes her school work seriously, unlike one of her siblings, who refused to attend school beyond Grade 5.

But Mahobe, the eldest child, has to juggle many responsibilities beyond school: she’s the one who gets up first each morning, lighting a fire to boil water and helping her siblings prepare for school. If there are leftovers from the previous evening’s meal, these become breakfast; without leftovers, she does without food. When she gets home from the day’s lessons, at around 3pm, she washes her own and her younger siblings’ uniforms for the next day, prepares supper and does chores. She must also, of course, find time to do her homework.

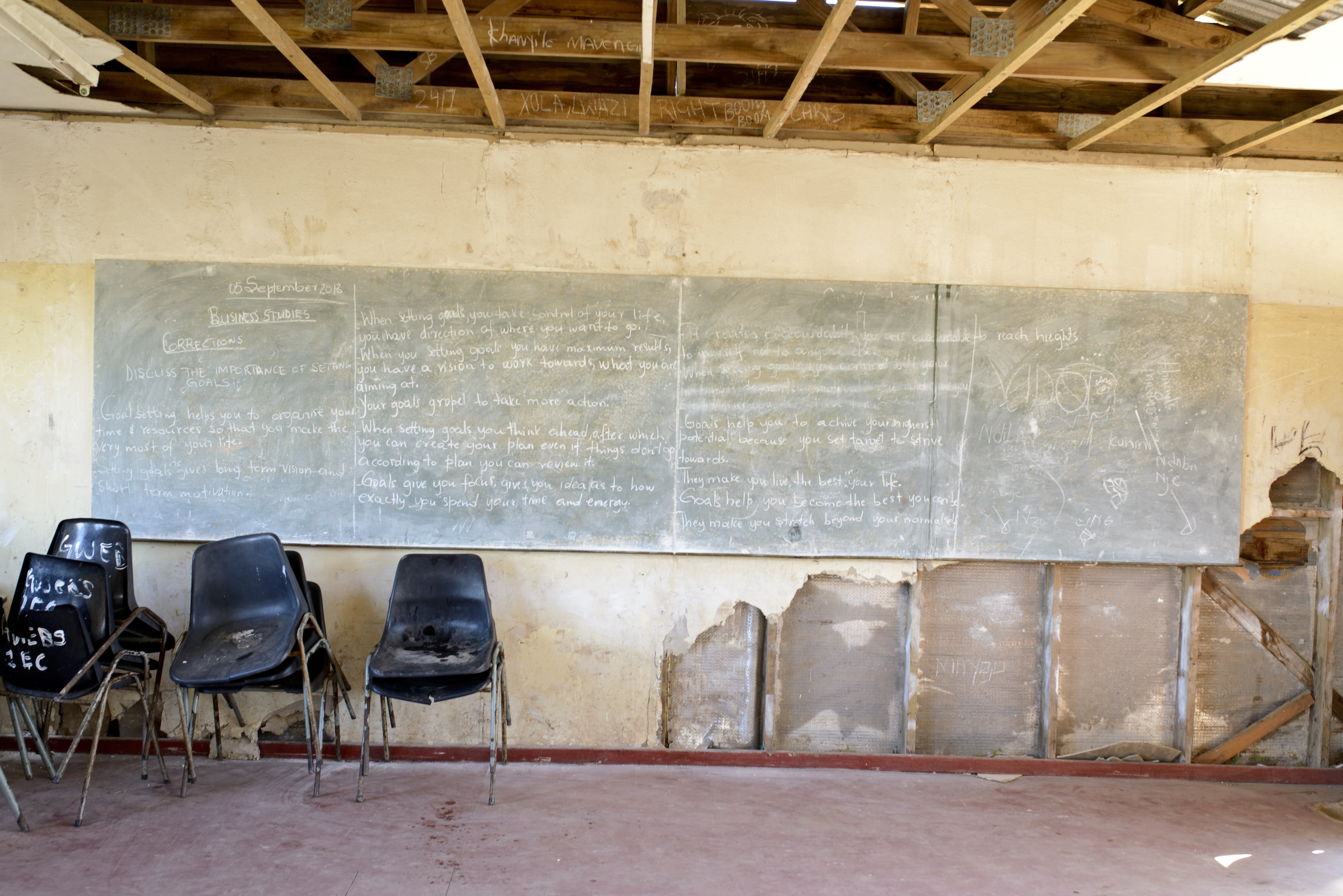

While some classes are in a good condition, there are still infrastructure improvements needed. Gwebityala Senior Secondary School, Elliotdale. Photo: Max Bastard

Mjali-Matyholo, too, has many hats to wear in a single day. In her office, the phone on her desk rings constantly; the school’s only printer and photocopier add to the clutter. If it’s not a phone call, it’s someone sticking their head through the door to report a problem or ask a question. The generator has run out of petrol, again. One of the school cooks wants to know if there are any bags of rice stashed away for that day’s lunch. “I’m being interviewed here!” she laughs; then relents, and explains where both the rice and soup packs can be found.

The school’s feeding scheme is run from a kitchen to the left of the main assembly point. Food is carried back and forth between the kitchen and a huge outdoor fireplace where cooks prepare lunch in traditional pots. Chicken or canned pilchards provide the protein; meals are served with rice, samp and pap. In hot weather, learners are occasionally served uphuthu (maize-meal porridge) and sour milk. For many, it’s the only meal they can be certain of each day.

Gwebityala Senior Secondary School, Elliotdale. Photo: Max Bastard

After a brief assembly each morning, learners head off to whichever of the 10 prefabricated buildings their first lesson is in – there are no permanent brick-and-mortar classrooms at Gwebityala. Mjali-Matyholo runs a quick staff meeting, and then the teachers go to their classrooms. Some of the classrooms are in such poor shape that even the snakes – which are a fairly common sight around Khotyana village – avoid them. Some classes are held outside.

There have been some physical improvements to the school. The community pitched in to raise money for an administration block about five years ago. The bathrooms, built by the Department of Education, are also new and in good condition.

Unfortunately for the school’s sportier learners, there are no sports facilities like soccer grounds or netball poles. In this area, soccer is extremely popular: after-school and weekend games are a common sight in the surrounding villages. The school fields a team but, out of necessity, it only plays away games.

Meals for the school nutrition programme being prepared outside. Gwebityala Senior Secondary School, Elliotdale. Photo: Max Bastard

Classrooms would really help the school to ease its overcrowding. A science laboratory, computer lab and a library would also be welcome additions – all of these, the principal says, would create more space for learning. And if promises were buildings, Gwebityala would be in great shape. For the past five years, Mjali-Matyholo explains, the Eastern Cape government has sworn that proper construction will begin… “soon”. The latest they’ve heard is that the project will be put out to tender for a contractor… also “soon”.

She’s quick to add that although the provincial government hasn’t delivered on its infrastructure promises, the Eastern Cape Education Department is a good source of support. Subject advisers and Educational Development Officers visit frequently, and the teaching staff has grown – thanks to the department supporting demands for additional posts – as more and more learners have flocked to Gwebityala over the past five years. Mjali-Matyholo beams as she recounts some of Gwebityala’s success stories. “Some of my former students are studying medicine at Walter Sisulu University. That brings joy to my soul as this is a poor community where most survive on social grants.”

One of the things that’s driven these achievements is a strong sense of discipline. Teacher and pupil attendance is consistently high. If pupils are late for morning assembly, they face detention or are made to sweep classrooms after school. Mjali-Matyholo says punctuality is good, and that learners “don’t have to be continually watched to do their school work”.

This discipline appears to have extended to other areas of school life, too. There’s no reported drug use at the school, and there have been no pregnancies this year. But, like any space full of teenagers, it’s not without its problems. Pupils are responsible for keeping the classrooms tidy. They often bunk that duty. Salespeople visit fairly often; their wares include shoes and hair pieces.

Still, the school seems to do a great deal with very little, in circumstances that are echoed around South Africa, and which often produce poor results. I ask Mjali-Matyholo, who is currently doing a Master’s degree at Walter Sisulu University, what is the value of education?

“It’s about empowerment. It helps pupils to gain real skills that directly apply to the world outside. That’s what they come to school for. As teachers, it’s our job to harness their skills.”

And are they getting it right? She is emphatic: “We are fulfilling that purpose with the little that we have.” The candles burning late into the night at Gwebityala suggest that she’s right. DM

Part 2

LM Malgas: Struggling in a storm

A normal week day at LM Malgas Secondary School is underway, and a Maths teacher is sobbing. Her pupils have decided they’re not interested in learning today; they didn’t do yesterday’s homework and they’ve walked out of today’s lesson. The teacher has been crying for almost 20 minutes, fruitlessly begging the pupils to return. She’s called colleagues in to help, and the principal, too. After a tense stand-off, the pupils agree to come back to class. But it’s a wasted lesson – one of several I witness during a week at the school.

Guest teachers are reluctant to teach at LM Malgas Senior Secondary School because of its remoteness. Photo: Max Bastard

LM Malgas is in Ramra village, on the outskirts of Willowvale in the Eastern Cape. The school has no electricity and relies on a water tank – if it runs empty, the school doesn’t have water until the next time it rains. And like so many of its counterparts elsewhere in the province and beyond, the ablution facilities are in a poor state. There’s one small, relatively new block with two proper pit toilets, and an old dilapidated block of pit toilets – literally just holes in the ground, with no doors for privacy.

This is a school that wears its financial struggles and a history of recent violence visibly. Fights that start over pots of traditional beer have sometimes spilled over into the school grounds, particularly during the province’s annual initiation season in June. A former principal banned pupils from carrying dangerous weapons like pangas, sticks and knives into the school; in response, a few learners wrecked huge swathes of the property.

Disrepair in the classrooms at LM Malgas Senior Secondary School. Photo: Max Bastard

Manelisi Mtshizana, who took over as principal in August 2017, sighs. The protests against his predecessor’s ruling eventually ended, but hostility lingered. The damage done during the protests to a room that was being used as the library remains untouched – teachers now use it as a staff room, marking papers or preparing lessons surrounded by messy piles of books.

Mtshizana identifies a library as being among the school’s greatest needs – so why hasn’t anything been done? He pauses. “We need a library assistant. We need someone who is trained to run the library.” That, he insists, is up to the Department of Basic Education to provide. And what about the broken windows, peeling paint and general disrepair? Can any of that be dealt with by the community, for instance? “The community says it can’t help with money – and we can’t afford to pay people if they do work on the school.”

The teachers at LM Malgas Senior Secondary School are overworked, but they are putting in a lot of effort to turn the school around. Photo: Max Bastard

That’s not to say LM Malgas’s staff aren’t trying to brighten their environment. There’s a small, neat garden where the vegetables used for the school nutrition programme grow. The grass that surrounds the buildings is kept trim, though both it and the vegetable garden are very dry, because there’s so little rain in the area. There is a space that could be used for sport, but it has become a communal grazing space for residents’ cattle.

It’s August when I arrive at LM Malgas for a week-long visit; my day begins at the flat of Nyanisa Ntshinka – a 45-year-old Life Sciences and Life Orientation teacher from the school, who is hosting me for the week. We wake up at 6am like she does every day; Umhlobo Wenene’s breakfast show provides the background noise, while she boils the first of three kettles: one for coffee, and two for a bath. Ntshinka is usually alone in the flat – her three children (14, 13 and four years old) all live with relatives at the family home in Mthatha. She commutes the 114km back home each Friday afternoon, and back again on Sundays.

The pit toilet block at LM Malgas is in disrepair with no doors for privacy. Photo: Max Bastard

Bathed and dressed, with her bags, papers and a Tupperware of cereal, Ntshinka climbs into a colleague’s car. They’re among the lucky ones who’ve managed to rent apartments close to Ramra village, and so – despite the state of the road – their commute isn’t much longer than 10 minutes. The school’s 120-odd pupils can travel up to 10 kilometres on a gravel road to reach LM Malgas, depending on which of the 10 surrounding villages they’re coming from.

Pupils are streaming in when Ntshinka and her colleague arrive. They gather outside, waiting for assembly to start at 7.50am. Teachers are charged with motivating the pupils during this eight-minute gathering, preparing them for the day that lies ahead. Attendance is good early on in the week; by Friday many pupils are absent.

One of the better-looking classrooms is dedicated to cooking at LM Malgas Senior Secondary. Photo: Max Bastard

But attendance doesn’t mean learning. Many pupils seem reluctant to be at school; some comment that they’re only there to please their parents, or to have something to do.

When teachers are called to meetings during class time, pupils don’t keep working – they wander outside, searching for shady spots in which they can chat or snooze. One day, I asked a few scattered groups from various grades why they weren’t in class. They shrugged. “There’s no teacher in class. Why should we be?”

Principal Mtshizana insists that his staff – though overworked and overburdened – are doing the best they can. When Mtshizana joined LM Malgas in August 2017, the school had only had temporary principals for years, and it showed. He describes the code of conduct as nothing more than words. Nobody enforced it, and nobody paid attention to it. Mtshizana says he’s since put his foot down – teachers are now at school on time and in class when they should be (although, yes, he concedes, they are sometimes called to urgent meetings during class time).

Schooling takes place among constant reminders of disrepair at LM Malgas Secondary School, Willowvale. Photo: Max Bastard

“Slowly the pupils are also getting in tune with being pupils, and their behaviour towards learning is changing,” he says. “They were used to not having a teacher in class. We’re changing that. Pupils used to bring dagga to school and smoke it in the toilets. Now we’re enforcing a culture of learning.” In another conversation, though, he worries that his pupils have “no hope”. He says: “They don’t see the point of bettering themselves. They want shortcuts.”

Perhaps the gap between what you see as a visitor and what Mtshizana and his staff believe they are achieving is an indication of how bad things used to be at LM Malgas.

Ntshinka is one of the teachers brought in to try and turn the school’s fortunes around. A lifelong educator and the child of two school principals, she left the profession after 14 years to concentrate on her hostel business. But she couldn’t ignore LM Malgas when it came calling in early 2018. It was in a slump; for the previous three years it had registered a less than 40% pass rate.

Learners at LM Malgas Secondary School, Willowvale. Photo: Max Bastard

Ntshinka isn’t a full-time member of staff. Rather, she’s employed as part of the Provincial Department of Education’s Learner Attainment Improvement Strategy. This is designed to improve learners’ marks, especially those who are in higher grades or already in matric. It’s a noble idea, but there’s a very serious drawback: at the time of writing this, she’d only received a single month’s salary for five months’ work.

On top of the financial strain, Ntshinka has also been tasked with teaching a subject in which she has no prior experience. She ought to have been hired as a Science teacher: she graduated from the then University of Transkei (now Walter Sisulu University) with a Bachelor of Science in Education in 2000, and previously taught Physical Science. But the school also needed someone to teach Life Orientation, so she’s taken on that too, and is learning on the job. She now teaches Life Orientation to the school’s Grade 8 and 9 learners, and Life Sciences to Grades 10, 11 and 12. Each lesson lasts for 55 minutes. It makes for gruelling days: sometimes she’ll teach from 8am until the end of the day, with only a lunch break.

The lessons after lunch are the hardest, because they’re often delayed – learners line up outside for meals from the school nutrition programme, that is coordinated by the provincial government. It serves rice, vegetables and fish on Mondays and Fridays; amasi (fermented milk) on Tuesdays; pap, vegetables and red meat on Wednesdays; rice, vegetables and chicken on Thursdays. It takes more than 30 minutes to serve all 119 pupils.

The fairly new school principal, Manelisi Mtshizana is desperately looking for ways to improve the situation at his school, LM Malgas Secondary School, Willowvale, Photo: Max Bastard

Despite the delay this causes in getting learners back into class, the teachers are pleased that the feeding scheme is available. For some learners, it’s their only full meal of the day.

Back in class, Ntshinka’s routine is always the same. The last 15 minutes of each lesson are dedicated to asking learners questions about the previous 40-minutes’ learning. She moves frequently between English and isiXhosa, a practice known as code-switching to help pupils grapple with new concepts in their home language. She also tries to keep the lessons interesting and relevant to the pupils’ everyday lives: in a Life Orientation class, for instance, she’ll explain why keeping fit is important for longevity.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t always work. The pupils are capable of reading aloud if she asks them to, but don’t participate much otherwise. Once, almost an entire Grade 10 class arrived without their textbooks; others had only blank pages where there should have been class notes.

She’d like to show them more images and videos to illustrate what she’s talking about, but there is only one computer at LM Malgas, and that’s mainly used for printing. Teachers occasionally use their cellphones as teaching aids, battling slow connections and limited data so they can find examples to engage their pupils.

“Our teachers are overworked,” concedes Mtshizana. “Sometimes the Department of Education helps here and there by providing temporary teachers, but we need more.” He himself teaches amid his other responsibilities, and finds it incredibly difficult to manage his load. “I’m robbing these kids. I can’t give them enough time.”

But, at a school where there is no-one to teach the learners Maths (they need to get Maths teachers in from neighbouring schools and it’s often a struggle), a lack of staff and resources are just some of the many issues impacting the school and its learners. Mtshizana believes that awareness campaigns about education are crucial to creating strong relationships between schools and communities.

He’s quick to add, though, that learners’ parents have been supportive of the school’s turnaround efforts. They scrape together what money they can to pay for sleepover study camps at LM Malgas, and now escort their children to night classes. For the most part, unfortunately, that support doesn’t extend to attending school meetings or doing homework with their children.

Drugs and alcohol are a problem, too. There are 11 known drug users among the pupils at LM Malgas. Some also engage in risky sexual behaviour; two girls were pregnant at the time of my visit.

The Department of Education has deployed a Learner Support Agent to the school. Her role is to provide counselling to the learners; she offers one-on-one sessions where they can discuss their worries and problems.

You’d be wrong to think that this school has nothing going for it, however. The teachers’ efforts organising group studies, where pupils play off each other’s strengths and learn from their collective mistakes, are slowly starting to pay off.

“The June exams saw an improvement, especially in the core subjects like Maths and Physical Science,” Ntshinka says.

Mtshizana is cautiously pleased about the results: “We are pulling through despite the conditions. In June, more than 70% of our pupils passed.”

But are the pupils of LM Malgas motivated enough to carry this performance through into the year’s final exams and beyond, to future grades? Ntshinka’s not sure. There are some bright spots: Cwenga Mtila, who’s in Grade 12, has banded together with some classmates to create study groups; they gather at break times and pore over their books and notes. They’ve gathered old question papers from their teachers so they can practice the work. And, in every class I attended at the school, there were always a few pupils who asked questions and engaged with the work.

By the end of my week at LM Malgas I was left wondering what, really, is keeping LM Malgas stuck? Are teachers to blame? Or pupils who don’t want to learn, and who sometimes choose knives over pens? Is it an education department that, Ntshinka suggests, “doesn’t care much”? Or communities wrapped up in their own daily struggles? To an outsider, it appears the school is in the eye of a storm created by all those circumstances. Mtshizana believes more staff, proper resources like computer and science laboratories, and better infrastructure will do the trick. DM

This edited article forms part of a publication called Human Factor that in its first issue looks at South Africa’s education system from the perspective of teachers (access at dgmt.co.za).

For more information or for interviews about the content discussed in Human Factor please contact Corné Kritzinger at [email protected] or 021 670 9840.

View the full Human Factor on this link: Human Factor

View the individual articles here: Human Factor articles

Ziyanda Zweni is a Public Relations Management graduate from Walter Sisulu University. She started working for Daily Sun as a freelance general photojournalist in 2016 and continues in this role. She also freelances for the Daily Dispatch newspaper in Mthatha. She previously worked for Ikhwezi laseMthatha, a community newspaper in Mthatha, as a general news reporter.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider