Southern Masters

The Poet of Place

How a soulful architect is changing the Southern landscape—one house at a time

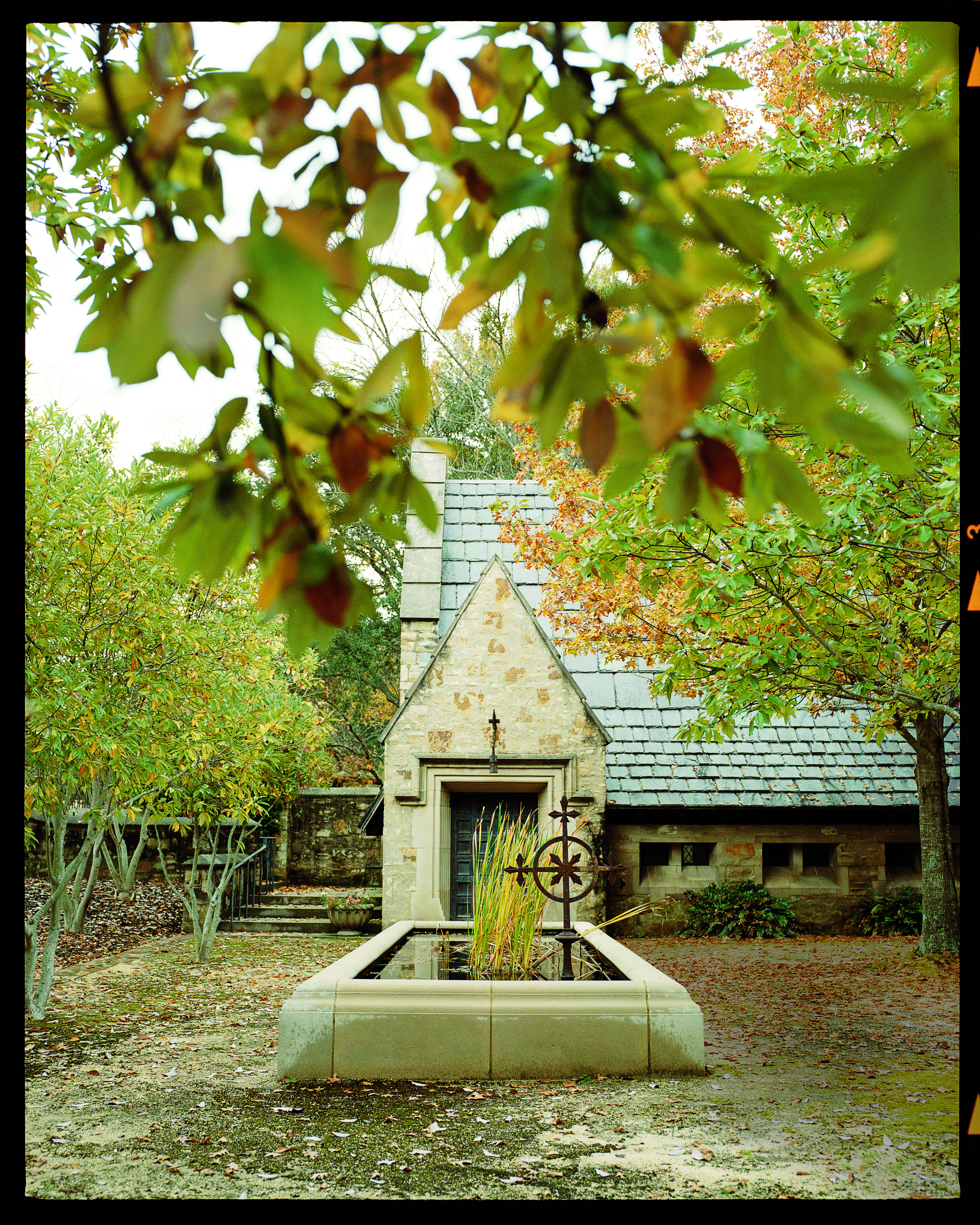

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

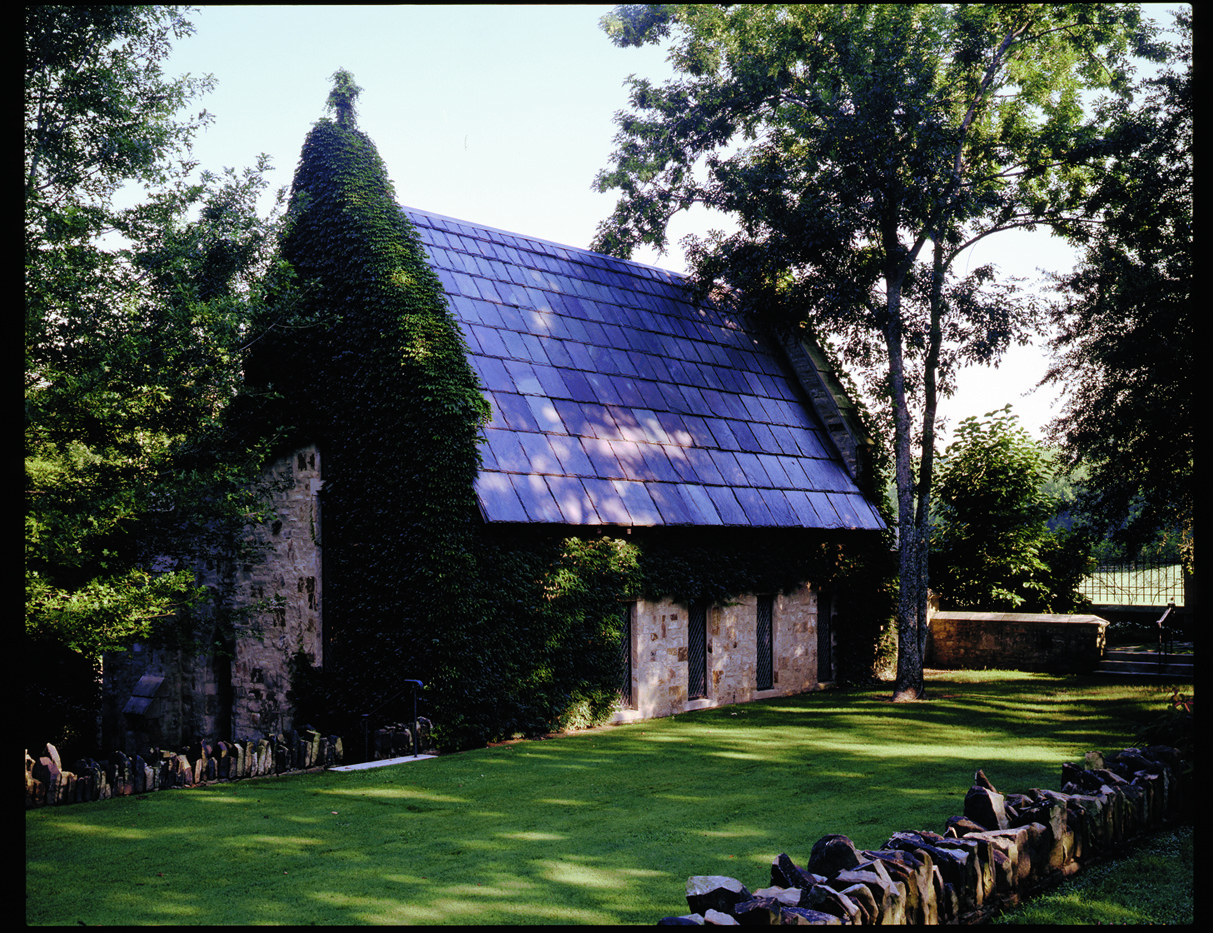

When I asked the Southern architect Bobby McAlpine to show me something he designed that was especially meaningful to him, I expected his choice to be a house. His work, after all, is 99 percent residential, driven by what he calls “an insatiable hunger for finding home.” Instead, one day last fall, he drove me to a chapel on a private estate buffered from the creeping sprawl of East Montgomery, Alabama, by woods and rolling pasture. McAlpine parked his Mercedes sedan in front of an imposing redbrick Georgian house, whose buttoned-down symmetry there at the end of a long drive seemed familiarly Southern. Turning our backs to the house, we wandered down to a hollow where a small stone chapel was stitched into the folds of the earth by a series of vine-choked rubble walls. Moss-covered fieldstones, lancet windows, steep-pitched slate roof—we could have stumbled upon an English church that had weathered four hundred autumns, except that there were no Englishmen here four hundred years ago.

The man who commissioned the chapel and once lived in the respectable house, Wynton M. “Red” Blount, had been a prominent Alabamian—builder of the Superdome, U.S. Postmaster General (the country’s last) under Richard Nixon, powerful philanthropist.

“I could have put this on a knoll,” said McAlpine in his quiet way as we paused before the chapel’s heavy wooden door, and many an architect would have done just that. “But there’s humility implied by traveling down.”

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

Blount Chapel, 1997, Montgomery, Alabama.

Though humility is rarely associated with great architecture, it’s Bobby McAlpine’s secret ingredient, one reason the Montgomery-based architect’s phone has not stopped ringing since he started practicing twenty-five years ago. Speaking in the language of timber, stone, plaster, and glass, he articulates the intangible qualities of home: a sense of place, communion with nature, permanence, but also peacefulness, security, grace, fellowship, hope, and, yes, humility. To him, a home should be a warm and trusted friend, if also glamorous and occasionally exhilarating. He couldn’t care less about stature or curb appeal or resale value. Hell, he doesn’t even know what a house looks like until he has almost fully conceived it—and that’s the very language he uses, as if he will be giving birth by putting pen to paper. He starts with floor plans—the faceless soul of a house—and lives with them until they have reached the end of gestation. Only then does he begin to envision the flesh.

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

An intricate scale model at McAlpine Tankersley Architecture.

“Bobby doesn’t intellectualize his buildings. He approaches them more from a spiritual standpoint,” says Ken Pursely, who studied under McAlpine at Auburn University and who later worked for him for eight years before opening his own firm in Charlotte, North Carolina. “So many people who work in a traditional palette follow rules and regulations, reference books and maxims handed down from architects like [Andrea] Palladio. Bobby looks at things more from a human or emotional aspect. How a space feels is more important than if it’s traditionally right or wrong.”

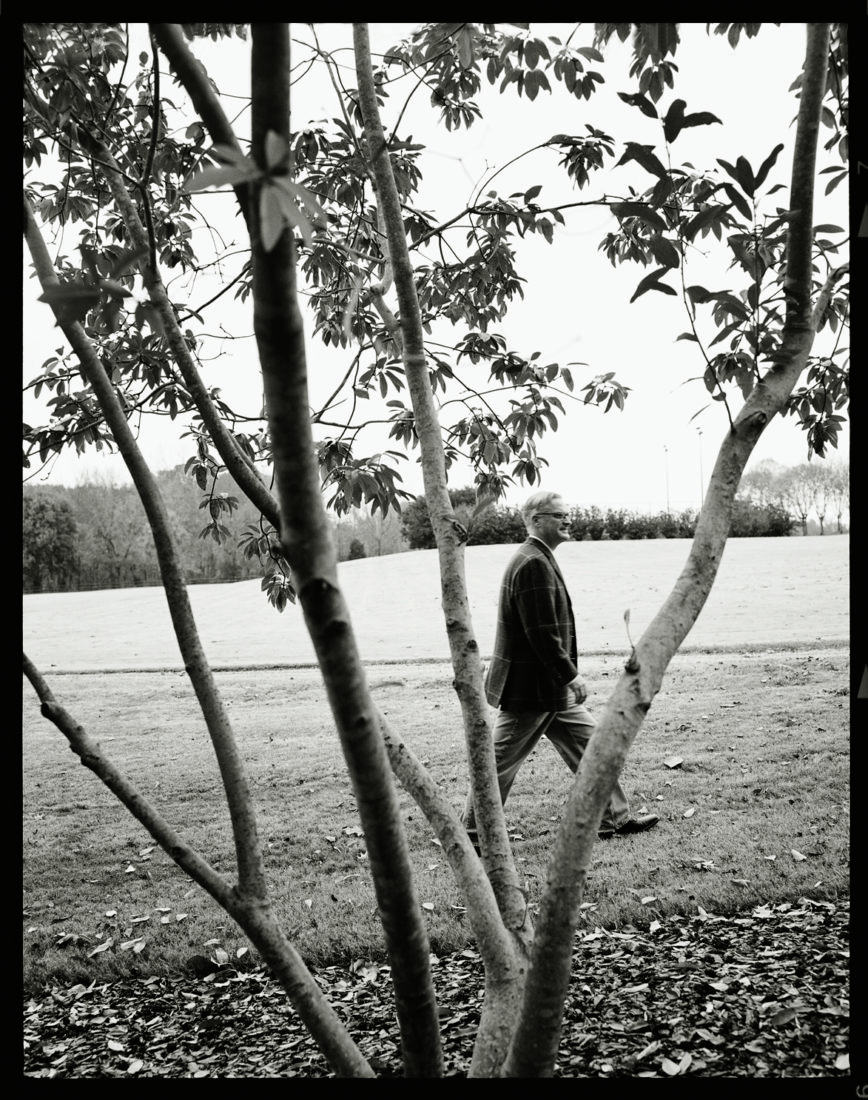

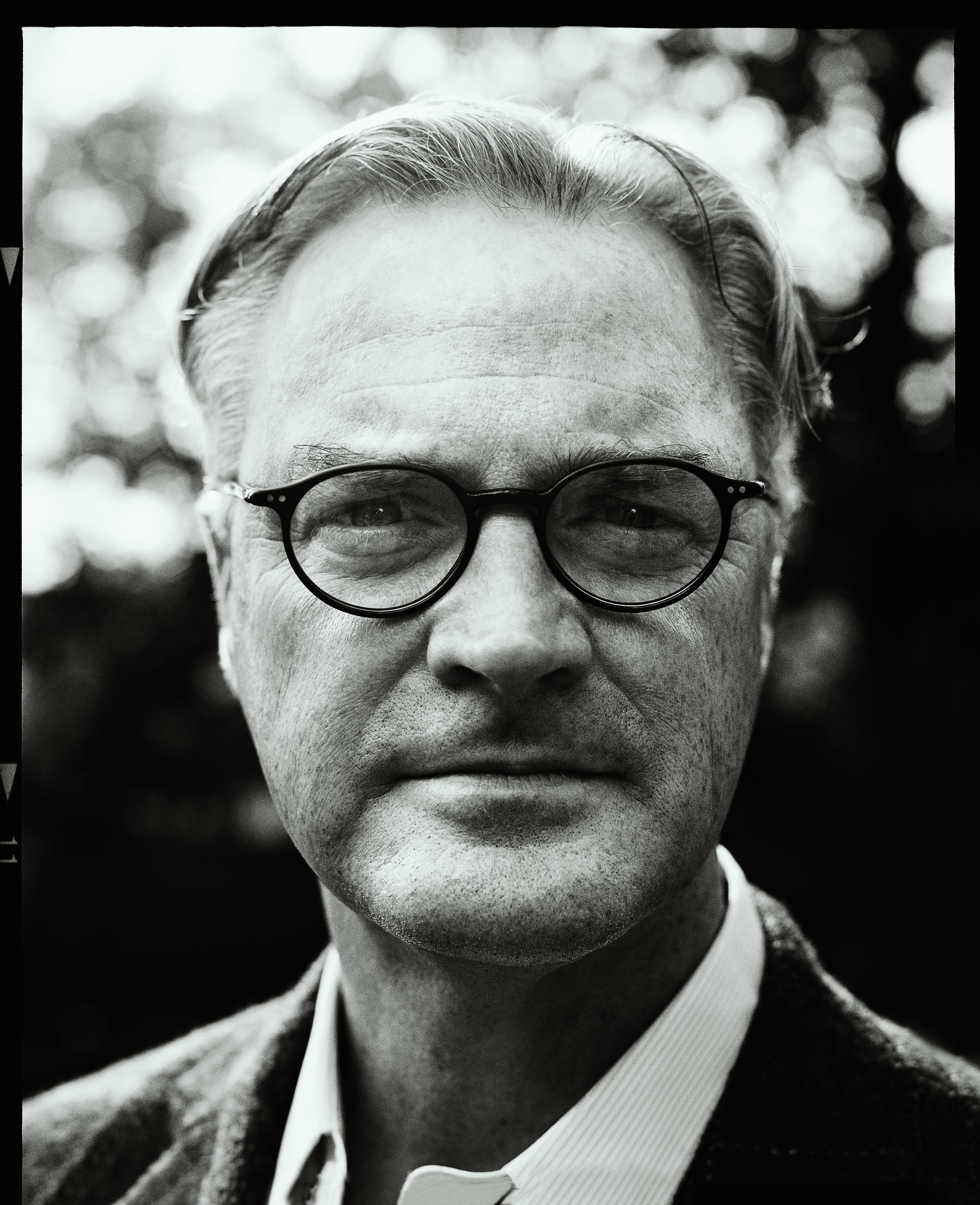

Over the past quarter-century, McAlpine, a silver-haired fifty-one-year-old who speaks with a soft Southern lilt, has designed more than five hundred houses with the help of his firm, McAlpine Tankersley Architecture, which he has stubbornly kept in Montgomery (even though he moved to Nashville nine years ago). McAlpine is famous in the South because he is of the South, and he takes into consideration the things his fellow Southerners cherish—history, tradition, the land, a welcoming energy, and the poignant beauty of shabbiness and decay. His work is at once rustic and tailored, nostalgic and modern. Though it’s early in his career to start talking about legacy, that’s the quality for which McAlpine will most likely be remembered—the loving spirit he infuses into his homes.

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

Bobby McAlpine.

A Self-Started Man

For an architect, Bobby McAlpine had about as unlikely a childhood as you could imagine. His parents married in their late teens and had a daughter in their mid-twenties. Around the age of thirty, his mother gave birth to a son, Robert Frank McAlpine. By then, Bobby’s father, who dropped out of high school in the tenth grade, was working as a sawmill boss in Vredenburgh, Alabama, a hundred miles southwest of Montgomery, a mill camp literally carved out of the virgin pine forests not far from the Mississippi border. Vredenburgh was a Faulknerian world where camp families bought food and clothing from a company store and tried to keep the red dirt out of their identical board-and-batten bungalows, which were hammered up out of the same pine that fell to make room for them. “It sent me inside to fantasize and create all the things that weren’t there,” McAlpine says.

At the age of five, when most children crayon a roof and chimney atop two walls and call it a house, Bobby started drawing floor plans. One of his first sketches was done in blue ink on the back of a Whitman’s Sampler box. “Momma said, ‘That’s very nice, but the dining room is nowhere near the kitchen,’” McAlpine recalls. “The funny thing is, I’ve never learned that. I still tend to make people walk.”

At age thirteen Bobby got his first commission to design a house from Miss Winnie Moody, a neighbor in Aliceville, Alabama. “She was one of the wealthiest people in town, but she was tight and not about to hire a real architect,” McAlpine remembers, so she paid him—exactly how much, he can’t remember, though it was less than $100—to draft a set of plans. “It was just a ranch house,” McAlpine modestly adds.

After living in six different burgs, McAlpine entered high school in Haleyville, a tornado-belt town in northern Alabama whose main industry was (and still is) mobile-home manufacturing. By chance, however, Haleyville claimed a single working architect among its ranks, and when Bobby was in ninth grade, that architect hired him as a draftsman. Up to that point, Bobby was completely self-taught, but not out of books. He climbed around job sites after hours, learning firsthand amid the blue chalk lines snapped on subfloors how to recognize floor joists and baseplates and stud walls. “It was a little more breaking and entering than anything academic.”

All that time, says McAlpine, his father, a backslapping man who spent his days in the rough-and-tumble world of the lumber business, “didn’t know what the hell to do with me or how to relate to me. I was the consummate nerd coming up. I didn’t do sports or band or clubs or anything.” Finally, father and son found common ground when the McAlpines decided to build a new house. “You draw it, son, and I’ll build it,” his father told him. Bobby was sixteen when the construction was complete. “We were close forever after that.”

Where It All Happens

Bobby McAlpine and I were seated at a round conference table at the offices of McAlpine Tankersley Architecture in Montgomery’s Cloverdale neighborhood. Around us, theater curtains spilled from steel rods, giving shape and texture to the cavernous second-floor loft. A dozen or more people leaned over drafting tables, penciling away on broad, crisp sheets of paper. Every home the firm designs is drawn by hand, down to the individual wood roofing shingles on the exquisite scale models. (“It communicates quality,” Greg Tankersley, McAlpine’s partner, later explained. “You can drive down the street and tell which buildings were designed on computer. They have no soul.”) Everything around me was so, well, architectural—and there was Bobby McAlpine showing me a set of crumpled 4-by-5-inch pages, peeled from an everyday notepad and inked to the margins with loosely rendered floor plans of a house for a Tulsa oil prospector. McAlpine, I was surprised to learn, does most of his work back-of-a-napkin-style on telephone notepads.

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

McAlpIne’s sketches.

“What’s up with this?” I asked.

“Because,” he said, tilting his head down and peering over his horn-rimmed glasses, “I’m a nomad.” He gathered the papers and made a motion of tucking them into the breast pocket of his tweed jacket. Always on the go, McAlpine works in inspired bursts in coffee shops, bars, and airport lounges. “Most houses come to me in flashes,” he explains. “The faster they come, the more I trust them.”

Bobby McAlpine is a romantic, a fact he freely admits. “I’m not a classicist,” he says by way of contrast. “I don’t see houses as objects. If you go by a big-columned classical house, and the primary emotion it evokes in you is ownership—wouldn’t it be great to own that—that’s one thing. But if you go past a house, and your primary instinct is how wonderful it must be to be behind that window, then I promise you that was a house conceived with the intimacy of its interior as its primary driving force.”

Despite his disregard for the plantation mansion, so many of McAlpine’s sensibilities trace back to his Southernness. “I don’t look to Southern architecture for inspiration,” he said. “I look to Southern people, the way the isolation and rural context and heat of the South breed a different kind of character. There is a willingness in Southerners to embrace eccentricity in people, and it’s that kind of gladness and inclusion that I find most inspiring.” Those feelings translate into bricks and mortar in many ways—in a graciousness of proportion, in a less formal bleeding of rooms into rooms, even in the unhurried pacing of a long, winding entry that allows guests to decompress and drink in their surroundings.

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

McClellan House, 1999, Nashville, Tennessee.

McAlpine also recognizes the deep connection Southerners feel to the land. If the typical Georgian box, beautiful though it may be, parks its haunches on the ground, peering out through punctures in its beefy container, McAlpine’s houses—narrow, linear, glass-filled, inspired more by modernism—engage with the earth, delivering its inhabitants into the landscape.

I saw firsthand how McAlpine blends traditionalism and modernism later that day when we parked alongside a stucco cottage with a sweeping shake roof he designed for himself in 1995. Though he sold it in 2004 to one of his junior partners, McAlpine still considers this home something of a self-portrait (see “The Work of Bobby McAlpine,” page 82). At first blush, it looked quite traditional—divided-light windows, chimney pots, even a few Tuscan columns along what I took to be the front facade. But then I realized the front is actually the side, and those columns are actually pilasters flanking towering living room windows and supporting an elegantly cantilevered shed dormer, all of it obscured by a hedge. At either end, massive bay windows project from second-story bedrooms. The designer balanced these grand gestures with the self-deprecating swoop of the roofline—the house “bowing its head a bit so it’s not so confrontational.” The same contrast occurs again inside, where low ceilings in the entry and kitchen feel cozy but the adjacent living room ceilings soar upward, lifting the eye and opening the space.

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

McAlpine’s first house, 1995, Montgomery, Alabama.

“The lowering and raising of ceiling heights is Frank Lloyd Wright 101,” says Pursely, McAlpine’s former student and colleague. “With Bobby’s work, the skin is traditional, but the DNA is modern.” He draws from such a broad vocabulary in pursuit of a timeless look—houses, in McAlpine’s words, “without an expiration date, but also without an inception date,” what he calls the “inheritable house.”

When Bobby McAlpine talks about architecture, he’s really talking about people. By all accounts, he is very good at connecting with others. Like a poet, he’s intuitive—even when a client may think he wants one thing but really needs something else.

Photo: JOE PUGLIESE

The entrance to Blount Chapel.

JOE PUGLIESE

Take the case of the Blount chapel. Red’s son, Tom Blount, himself an architect, originally introduced McAlpine to his father, recommending that he design the chapel. “I didn’t want anything to do with it. It was too personal, and I knew that both Dad and his wife, Carolyn, had totally different ideas about what it should look like,” recalls Blount, who lives in Los Angeles. “Carolyn thought it should be a little carpenter-Gothic church, and Dad, who was always thinking monumentally, probably pictured the Cheops Pyramid. I was in the room with Dad and Carolyn when Bobby told them the church he wanted to build did not look like what either wanted.” McAlpine started describing something totally different—a tiny stone chapel, just eleven feet wide, cupped by the earth, with an entry off to one side so that visitors could enter unseen. “It was just brilliant. Bobby had a perfect understanding of how to communicate with them. They were like purring kittens.”

Today, the loving couple is joined together beneath a single headstone, designed by Bobby McAlpine, behind the chapel—their eternal home.