How Both Parties Lost the Texas Senate Race

In the race between Ted Cruz and Beto O’Rourke, Republicans failed to recognize the ways in which the state is changing, while Democrats didn’t take seriously just how far it still has to go.

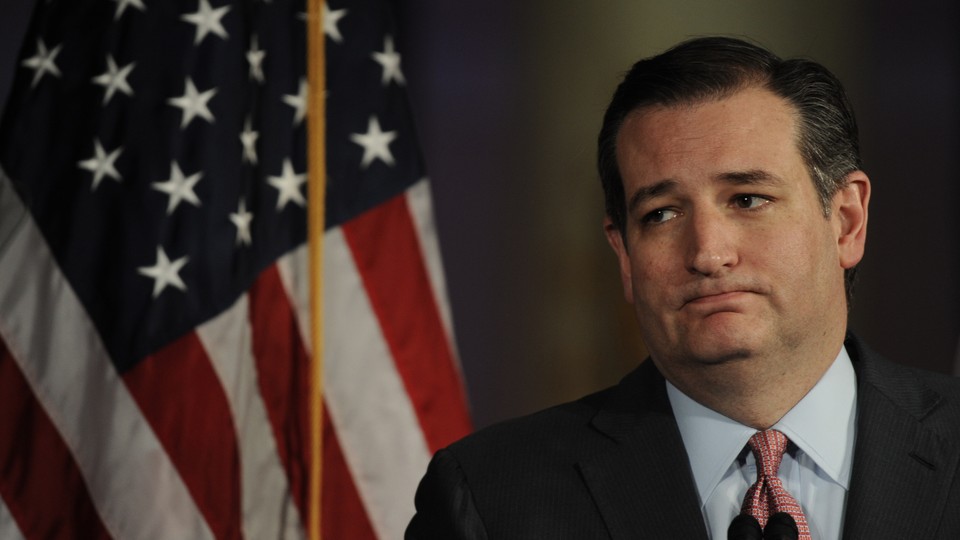

On Tuesday, Texas voters did as Texas voters historically do: They sent the full slate of Republican statewide candidates back to office. Those candidates faced varying degrees of difficulty—Senator Ted Cruz crawled his way to victory; Governor Greg Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton enjoyed more of a brisk sail—but the result was the same. The Republican Party maintained its grip on the state that so many believed would, at long last, go blue.

After two years of being barraged by books and articles forecasting a shift in Texas’s political alignment, Republicans might view Tuesday’s elections as a satisfying rebuke to that narrative. And in some ways they’d be right to: The national media’s coverage of Cruz’s Democratic challenger, Beto O’Rourke, who represents the state’s 16th Congressional District in the House, seemed to verge, in some cases, on the sycophantic, and I talked to no shortage of Republicans who delighted in O’Rourke’s loss not so much for Cruz’s victory but for the image of reporters and pundits tucking their tails. Yet another election, their thinking went, in which the gulf between coastal elites and real Americans was laid bare.

As I wrote last night, O’Rourke’s loss stemmed in part from his inability to package his progressive vision in a way that proved palatable to the majority of Texas voters. Earlier this year, a Democratic representative up for reelection in a very liberal district, who requested anonymity for fear of backlash, told me he didn’t dare touch impeachment on the stump—it was too volatile a topic, he said, especially with low-hanging fruit such as health care and immigration up for grabs (this person won handily on Tuesday). It was curious, then, to see O’Rourke, in a state as red as Texas, tackle impeachment and other far-left proposals, such as the abolishment of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, head on.

But in critiques of O’Rourke’s strategy, the deficiencies of his challenger—and the GOP as a whole—become just as clear. Texas may play host to mostly conservative voters, yes. But massive early-voting numbers and record turnout among minority demographics reveal that the state is shifting not so much in how its citizens decide to vote, but in who decides to show up. “A lot of the patterns last night were predictable,” the Republican strategist Liam Donovan told me. “It was the volume that caught everyone by surprise.” For Cruz, the blind spot was telling: His campaign based its electoral models on 6 million voters, far shy of the 8 million who ultimately turned up to vote. It’s the kind of miscalculation that, if replicated, could spell doom in the future for Republican candidates in Texas and beyond.

All of which is to say that in Texas last night, both parties lost in their own way: one by not recognizing the significant ways in which the state is changing, and one by not taking seriously just how far it still has to go.

Perhaps the best way to understand O’Rourke’s and Cruz’s missteps is to study the Democratic upset in Texas’s Seventh Congressional District. The seventh, which includes the Houston suburbs, has long been one of the most reliable Republican districts in the country. Before last night, it hadn’t gone blue since before 1966, when George H. W. Bush won the seat. John Culberson has represented the seventh for the last 18 years. He was never a familiar face nationally, but as a senior member of the powerful Appropriations Committee, he had an institutional cachet that was tough to challenge.

But as anti-Trump resentment grew in the aftermath of the 2016 election, a lawyer named Lizzie Pannill Fletcher, then 41 years old, decided to do just that. She was certainly liberal, once serving on the board of Planned Parenthood. She was young and inexperienced and felt a high-minded calling to try to check the “culture of cronyism, corruption, and incompetence” that she told me she saw unfolding in Washington.

In other words, she was a lot like Beto O’Rourke. And after Fletcher won the Democratic primary, the race for the Seventh Congressional District began to bear resemblances to the Senate contest. Nationally popular Democrats such as former Vice President Joe Biden started to take notice, and Democratic strategists in Washington began to view the historically deep-red district as one of the key pickups in their path to taking control of the House.

As the interest in Fletcher’s campaign grew, it was as though Culberson had been jolted from a long sleep. “We’ve been trying to tell him all summer, ‘You know, this isn’t a joke. It’s not like all the other times. We need to actually get moving,’” a source close to Culberson, who asked that his name not be used so as not to jeopardize their relationship, told me in August. Suddenly this institutional presence who’d long ago absconded with the need to seriously campaign had to, well, campaign.

That’s not a perfect parallel to Ted Cruz, necessarily, whose team early on readied for the national fanfare around O’Rourke. But it reveals how the competitiveness and hype that were building ahead of the 2018 elections seemed to sneak up on Texas Republicans—how the popular mood of discontent with Washington could actually motivate new and more voters to turn out. As Politico first reported, the Cruz team’s prediction of total turnout never strayed from 6 million to 6.5 million. All told, the number of voters in the Texas Senate race easily broke 8 million.

How was Fletcher able to spin groundbreaking turnout to her benefit while O’Rourke wasn’t? There are dozens of answers to that question, including the coattail effect, in which the popularity of one candidate helps boost another down-ballot: Most strategists I’ve spoken to believe that having O’Rourke at the top of the ticket helped usher Fletcher over the finish line, whereas O’Rourke, with popular Republican Governor Greg Abbott at the top of ticket, enjoyed no such luxury.

But the coattail effect alone cannot explain how Fletcher managed to trounce Culberson by a massive five percentage points. The answer may be that, unlike O’Rourke, Fletcher politely eschewed a surplus of the national spotlight in favor of a hyperlocal campaign. When I interviewed Fletcher in August, she repeatedly dodged questions about whether she’d support Nancy Pelosi for speaker, for example, or whether she would move to impeach the president once she was in Washington. Rather than indulging such questions, she consistently attempted to reroute the conversation back to district-specific issues, such as the devastation wrought by Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Likewise, she hardly mentioned Donald Trump, clarifying that she was running against Culberson—not the president.

Compared with House races, of course, Senate races will always generate more buzz, will always attract more glossy magazine profiles. It’s not O’Rourke’s fault that the national party adored him and that untold millions of dollars flooded in from across the country. Rather, it’s a testament to his strength as a politician—one can see why, after listening to O’Rourke’s speech about his support of NFL players who were kneeling during the national anthem, party leaders saw a star in the making.

But it’s one thing to be a good politician; it’s another to run a smart campaign. Perhaps Fletcher’s greatest strength was campaigning on the assumption that while demographic trends in the majority-minority district favored her platform, those voters were unlikely to turn out. In order for Fletcher to win, she’d have to pick off as many of the district’s budding population of independents as possible, as well as any Republicans disenchanted by Culberson. Which is to say that when the turnout of young voters and nonwhite voters vastly exceeded expectations, it was a nice bonus for Fletcher rather than a godsend. By rooting her campaign in crossover appeal, she was able to reach not only the district’s Democrats—whose turnout was historically unreliable—but also, more important, voters in the center and even just to the right, whose turnout was a given.

One of the biggest pitfalls of O’Rourke’s campaign was that there appeared to be no sincere effort to reach such voters. “Despite all of Cruz’s problems—and there are plenty—here’s a guy who’s running around talking about Medicare for all, and impeaching Trump, and abolishing ICE. And it’s killing him,” Karl Rove, the former senior adviser to George W. Bush, told Politico. “Even for people who dislike Cruz, impeaching Trump strikes many of them as terrible for the country. I’ve got friends and family members who may not vote for Cruz. They don’t like Cruz. But Beto isn’t contesting [Cruz for] them. I mean, it’s just weird.”

But this is the rub for Republicans: Ultimately, O’Rourke lost by just a two-point margin, making the race far closer than expected. It’s tough not to wonder, then, what this race might have looked like had O’Rourke courted the center. Would it have looked like Lizzie Fletcher’s, another talented progressive besting a conservative name brand? Would the presidential-year-like turnout of new voters, young voters, and minority voters have merely sweetened a victory rather than ensured a less painful beating?

These are the questions Texas Republicans must ask moving forward. In vastly underestimating turnout across the state, Republicans hadn’t just laid the groundwork for a potentially humiliating loss. Much more crucially, they’d revealed, perhaps, how little they understand the state itself. Because while Texas is far from blue today, Tuesday showed that there are plenty of voters—millions, in fact—who are eager to make it so tomorrow.