A writer and self-confessed avoider of the limelight, Nell Scovell is hardly a household name. But somehow over the past three decades, she has been part of almost every interesting comedy scene around, writing for Spy, The Simpsons, Late Night With David Letterman, Murphy Brown, The Critic, and Mystery Science Theater 3000, among many others. More recently she collaborated with Sheryl Sandberg on the highly successful if less amusing Lean In.

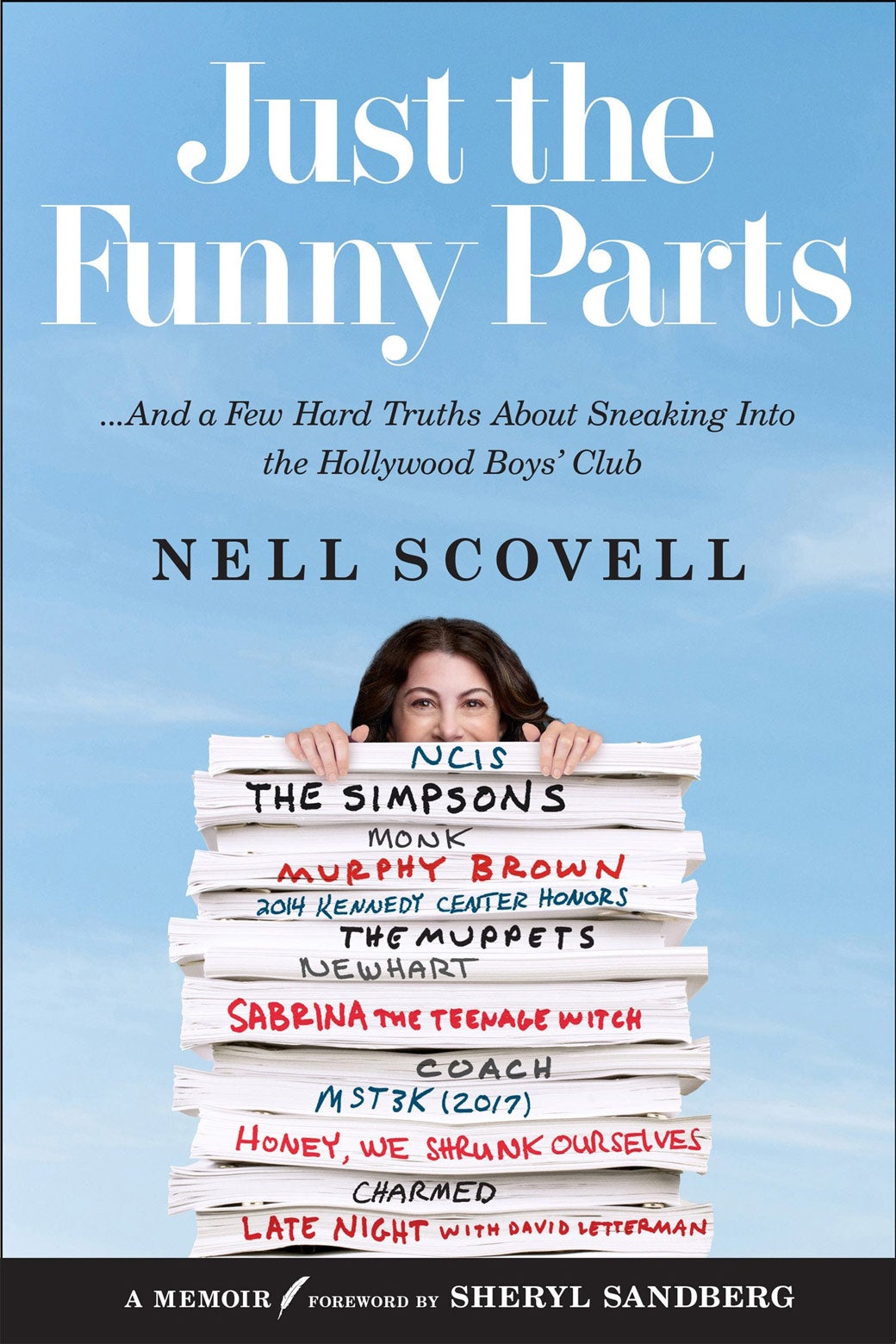

Now Scovell has written her own book, Just the Funny Parts … and a Few Hard Truths About Sneaking Into the Hollywood Boys’ Club, part personal memoir, part overview of why television comedy writing staffs are not exactly hotbeds of diversity, and part expert guide to forging a career as a comedy writer.

This third part will be fascinating to those interested in how the comedy sausage is made. She breaks down the television show scriptwriting process from initial pitch to structuring the episode, the scene-by-scene outline, the first draft, and ultimately the shooting script. Even more importantly, she reveals how a writer should respond to feedback, like this hint on getting notes from the network, adapted from advice to demonstrators confronted by police: “Go limp,” the book counsels, “Don’t stiffen up and don’t fight.”

One of the most startling revelations is the mayfly lifespan of television writing jobs. By any measure, Scovell was and is a successful writer, yet within one year (1989), she’d been hired as a writer by three different series (The Wilton North Report, It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, and a revival of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour), but none of these jobs lasted longer than three months. A stint at Newhart lasted nine months, Coach for two years, and The Muppets for one year. A chronology of her writing jobs included in the book is studded with “unshot” spec (i.e., uncommissioned sample) TV pilots, “unsold” spec movie scripts, and produced but unaired episodes.

Aspiring scriptwriters may find this both inspiring and depressing. Inspiring because if even a highly regarded known quantity like Scovell, who is represented by a top agent, has written so many projects that don’t get off the ground, it can happen to anyone. And depressing because if even a highly regarded known quantity like Scovell, represented by a top agent, has so many projects that don’t get off the ground, the odds of an unknown’s script getting made are infinitesimal. The key to success, Scovell suggests, is to ignore the odds and risk rejection. “Writing is not what you start,” she notes in perhaps her most useful piece of advice. “It’s not even what you finish. It’s what you start, finish, and put out there for the world to see.”

Her own attitude is philosophical. “I learned not to get too happy about good news or too distraught about bad,” she says, quoting a friend who told her to “be as happy as you can be for as long as it lasts, but sustained joy is not part of the deal.” It is clear the most valuable attribute for the aspiring writer is resilience.

The memoir aspect suggests that these opportunities have arisen from a combination of a good network and a keen eye for maximizing the potential of that network. For example, Scovell’s big break was being hired as Spy’s first reporter. She got the job by pitching 10 good story ideas when she met with editors Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter, but she got the meeting because the new magazine had approached her then-husband in search of investors. An acquaintance who is a former editor of the Harvard Lampoon then sent some of her Spy articles to his agent. The same agent represented Al Jean and Mike Reiss, at the time working on Shandling’s show. Her commissioned but never shot script for Shandling got her the staff writing job on Newhart. Later on, she connected on Facebook with an old college (Harvard, natch) friend who just happened to run the company’s media and communications department. This led to providing occasional jokes for Mark Zuckerberg’s speeches, which led to writing a speech for Sheryl Sandberg, which led to Lean In.

As the subtitle suggests—and the many candid photos in the book confirm—what makes Scovell’s story especially interesting is how she was so often the only woman in the room. At Harvard she eschewed the comedy farm team of the Lampoon in favor of becoming a sports correspondent for the campus newspaper, the Crimson, and later she covered sports for the Boston Globe. So when she interviewed to become the first female writer on Late Night With David Letterman since the departure of original head writer Merrill Markoe, she was able to knowledgeably talk football with the late-night host. “I was a good ‘culture fit,’ ” she writes, with the advantage of genuinely liking sports and pizza (and being a sci-fi nerd, and being white).

The ability to hang with the guys extends to her personal life, where she becomes best buds with magician Penn Jillette of Penn and Teller and joins his otherwise all-boy crew. Jillette introduces her to her next husband, an architect, who, Scovell acknowledges, made it possible for her to progress in her career by being happy to be their sons’ primary caregiver (bearing out her future collaborator Sandberg’s observation that a woman’s most important career choice is the partner she chooses).

However, Scovell, who comes across as quite a good egg, eventually comes to see it is not enough to break through the glass ceiling herself but that she also needs to use the leverage she has to help people who may not be such good culture fits. “Only later would I learn what journalist Alexandra Petri perfectly expressed in this tweet,” she writes, quoting, “if you are the only girl in a room it doesn’t mean you’re better. it means something is wrong.” As a result, she now uses her impressive connections to help young women break into television comedy writing.

If the book lacks the pungent tang of burning bridges that made Julia Phillips’ You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again so compelling, with Scovell more inclined to salute “brilliant” or “generous” colleagues, she does settle a few scores, most notably with the head writer on the Smothers show, about whom she tells her own chillingly described #MeToo story.

Nor has time softened her view of Letterman (who, to be fair, comes across as more misanthropic than purely misogynistic). In 2009, Scovell wrote a bombshell article for Vanity Fair (the overachiever has a sideline as a journalist writing for prominent publications like VF, Vogue, and Rolling Stone) about the generally female-unfriendly climate on his show. Over the years, Late Night and the Late Show had hired only seven female writers, compared to more than a hundred men.

This demographically monolithic approach limits not only female writers’ career possibilities but also the scope of material perceived as having comedic potential. As Scovell says, “emotions are universal but experiences are not,” and stereotypically female topics like, say, giving birth or motherhood are perceived as not nearly as funny as masturbation or farting.

This raises the question of whether comedy writing can escape silo-ization. Scovell herself admits that although as creator and showrunner of Sabrina the Teenage Witch she hired several female writers, “we didn’t have any writers of color … I had the opportunity to include more voices and I didn’t make enough of an effort. That was a mistake.”

If this makes the book sound po-faced and worthy, it is anything but. There are loads of good jokes and sharp observations. And if Scovell’s perspective is more Clintonesque Ivy League reformer than paradigm-questioning subversive (jokes about Facebook, which certainly presents a giant target, are conspicuous by their absence), she offers an honest, demystifying glimpse into the world of the men (and some women) behind the comedy curtain. Like Liz Lemon, Scovell is a wry and relatively grounded observer of the soaring self-regard and bottomless neediness that characterizes the professionally funny. You come away convinced that 30 Rock and The Larry Sanders Show were not so much satire as documentary.