Andres Rubiano first got the news that his blood pressure was too high in the 1990s, when he was in his late 30s. It didn't come as a complete surprise—his father had had chronic hypertension at an early age too. His doctor prescribed medication and encouraged him to get more exercise and cut down on the amount of salt in his diet. Rubiano, though, wasn't very diligent about following this regimen. Each time he returned for a checkup, doctors gave him the same advice and Rubiano disregarded it.

Four years ago, something caused Rubiano to turn himself around. His doctor convinced him to enroll in a pilot project in digital health care. Once a day, Rubiano slipped on an automatic cuff that wirelessly sent blood pressure readings to his smartphone, which in turn relayed the data to a team of clinicians at Ochsner Health System, an academic medical center based in New Orleans. His Apple Watch relayed heart-rate and physical-activity readings. Soon, Rubiano was getting text messages reminding him to take his pills and emails suggesting ways to cut down on salt and boost physical activity. Each month, his doctor's office called to discuss his readings, tweak his medication dosage and examine new diet and exercise strategies.

The digital prodding paid off. Rubiano now takes his pills, goes to the gym three times a week and eats less salt. "I don't even like the taste of it anymore," he says. His blood pressure dropped from 150 over 100 to a reasonable 130 over 78.

Rubiano is an early beneficiary of a new data-driven approach to health care that is starting to take hold in the medical industry. As the fate of the Affordable Care Act plays out in the courts and politicians and patients wring their hands over the rising cost of drugs and treatments, a growing army of researchers, practitioners, entrepreneurs and executives think tech could be a simpler way to fix much of what ails the U.S. health care system. Essentially, they want to do for medicine what Facebook and Google did for social media and internet search. By gathering real-time data on patients and using it to prod, poke and persuade them to do the right thing, they believe that doctors could improve outcomes dramatically for patients with a broad range of chronic diseases and conditions, including heart disease, cancer, diabetes and Alzheimer's. "We can't just fix chronic disease; you'll have it until you die," says Richard Milani, a cardiologist who serves as chief clinical transformation officer at Ochsner. "We need to surveil you closely and catch you when you're heading out of bounds."

There are, however, clear risks. If you think Facebook and Google invaded your privacy, imagine what hackers could do with a minute-to-minute log of your disease symptoms, behaviors, locations and even your appearance and conversations. The key to digital medicine is, after all, the gathering and sharing of copious data about nearly every aspect of a patient's life. Are hospitals, researchers, Big Pharma, insurers and tech companies worthy stewards of such sensitive data? "If a system can detect signs of cognitive decline in patients' voices, they don't want it being used against them in job situations or health insurance," says Christine Lemke, co-founder of Evidation, a health data company.

If experts can figure out a way to lock down privacy, digital medicine could pay off big time. Its biggest impact is likely to be in chronic care. At present, U.S. health care is designed for crisis-oriented transactional care—you break your arm, the doctor sets it and you go home. That mode works poorly in early detection and treatment, which is what's needed to keep a patient with heart disease or diabetes from slipping into a medical crisis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 60 percent of the U.S. population has a chronic disease and that 40 percent has at least two. Heart disease, diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer's and stroke together account for almost three-quarters of all deaths in the U.S. and 86 percent of health care costs. Chronic disease is "the leading health burden on Americans," says Milani. "And it's where the digital piece can make its greatest contribution."

Digital medicine is a key tool in a broader trend toward "value-based" care, in which health providers are compensated not for each procedure they perform, which drives up costs, but for keeping a population healthy. That puts the emphasis on prevention, which is exactly what digital medicine is suited to. A whole new field of data-driven medical research has arisen to explore the links between health and genes, the environment and behavior. Researchers use artificial intelligence (AI) to digest this data and uncover important patterns.

There are indications that people would be willing to take the risk and trust the medical establishment with their vital signs and other intimate details. Millennials, despite Big Data hacks and abuse by tech companies, seem blasé about privacy but don't much like their health care. According to a recent Accenture survey, people aged 22 to 38 are up to three times more likely than older patients to express dissatisfaction with the health care system, and half of them are already using digital tools to self-manage some aspect of their health. Even Rubiano, now 58, says he doesn't mind having his vital signs digitized and shared in real time. "It's really made a difference knowing that someone is always watching over me through these readings, instead of waiting one or two years for anyone to notice," he says.

Beyond the Fitbit

A digital health industry has sprung up quickly in recent years. Investors inked almost 700 deals last year for nearly $7 billion, according to a study by Health Data Management, an industry journal. Billions more flowed from health care institutions to develop digital tools and start pilot projects and from tech giants like Apple, Amazon and Google, which are determined to capture market share.

Much of the investment is aimed at finding ways to collect health data that go well beyond conventional patient electronic medical records. Google's parent company, Alphabet, for example, runs a company called Verily that's partnering with Duke and Stanford universities to collect a broad range of data on 10,000 mostly healthy people. And Mindstrong, a Silicon Valley startup co-run by former National Institute of Mental Health leader Thomas Insel, is aiming to track people's behavior in order to catch early signs of mental-health and other brain-related problems.

Much of that data comes from the wireless gadgets that we have become accustomed to interacting with all day long. The worldwide market for smart watches and other activity trackers is now $6 billion and growing at 20 percent a year. Health care–specific trackers are also on the rise; entrepreneurs and investors aim to build an ecosystem of apps and gadgets that patients can pick and choose from to manage their medical data. Everything about your body, your behavior and your environment can be mined for insights. Scientists at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, for example, are developing a device that sits against the abdomen to listen to what goes on in the colon to understand digestion. A new watch from Withings monitors blood pressure and takes electrocardiograms. Data from Fitbit trackers alone has inspired 675 studies in health-related journals. Even the 50 million security cameras in the U.S. could be harvested for data on how fast, frequently and robustly you walk or run, and whether you look happy, sad, pained or confused.

Health care professionals call it "quantified biology." For years, medical researchers have been studying the genome, which is the sum total of an individual's DNA, and the proteome, which encompasses all the proteins a person's cells produce. Now, they are looking at the exposome, which contains data about the environment—the sounds, chemicals, people, sunlight and anything else that an individual encounters in life—and the behaviorome, which encompasses behavioral tendencies while eating, sleeping, exercising and beyond.

The data on exposomes and behavioromes is currently sparse, but that's changing. Yale biologist Caroline Johnson, who specializes in metabolomics—the study of chemicals that insinuate themselves from the environment into our bodies—notes that researchers have found 750,000 metabolites that are linked in some way to health issues. Emory University researchers have developed tests that can identify these metabolites in a urine sample at a rate of 1,000 per minute. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has set up a $1.5 billion program, called All of Us, that's planning to gather all sorts of tracking, environmental and other health-related data from at least 1 million people. One goal is to look for clues about how variables like exercise, diet, sleep and heart rate are linked to disease.

To get a sense of how this new "omic" data might improve health outcomes, consider Walter De Brouwer, a computational-linguist-turned-entrepreneur from Mountain View, California, who not long ago was having trouble sleeping through the night. Lack of sleep is linked to high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer's and even to cells' ability to repair errant genes. The sleep-tracking app on De Brouwer's Apple Watch confirmed that he was waking up twice each night. He found the first culprit by checking video from the security cameras scattered around his house: His son was making noisy late-night visits to the kitchen. A data dump from his smart thermostat revealed the second: a middle-of-the-night temperature spike in his bedroom.

De Brouwer channeled his data obsession into a startup called Doc.ai, which makes a medical app that automates the process of assembling its users' exposome and behaviorome. You start by taking a selfie, which the app's AI uses to estimate your age, height, weight and gender (the idea is to reduce the amount of information a user has to enter manually). Next, you enter your current and previous ZIP codes, which the software uses to query databases of air pollution. In the future, the company plans to add location-based data on water pollution, disease prevalence, mosquito counts and other data. Then, if you trust Doc.ai app, you grant it access to all your online health information—your health care provider's patient portal, labs where you had blood or other tests, the results of a 23andMe gene scan and so on. The final step is to connect the app to your phone's GPS, fitness-tracking watches and other smart devices. Doc.ia keeps all the personal information on your phone, says De Brouwer, not in the cloud, to keep it away from potential hackers.

Doc.ai is just one of many startups that aim to be the go-to app that patients can use to manage their health data. The company signed up 35,000 people in six months, enough to run some statistically meaningful trials. It is partnering with health care providers, insurers and research institutions to offer its users opportunities to put that data to work in managing their own health, or contributing to research, or—as is typical in medical studies—both. Each user decides on a case-by-case basis who gets what data for which study or service. So far, Doc.ai has offered its early users access to an allergy research study in partnership with Harvard Medical School and health insurer Anthem—the 2,000-person study filled up in three weeks, with another 8,000 on a waitlist. Studies on Crohn's disease and colitis are live, and epilepsy is coming.

Converting Data to Health

Although the field is new, health care organizations are already exploring ways of applying data to care. Ochsner's blood pressure program has enlisted more than a thousand patients, and the numbers are encouraging: 79 percent manage to keep their blood pressure in safe territory, compared with 31 percent for the hospital overall. In addition, Ochsner has set up a digital program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, nearly a third of whom wind up in the emergency room at some point gasping for air, which is traumatic and imposes enormous costs on the system.

To head off these crises, doctors at Ochsner wired their patients' inhalers to alert them to patterns of usage that signal growing respiratory distress. Those patients get a text or call at home suggesting a change in medication or prompt a checkup. Patients also get text alerts when air particle readings are dangerously high in their communities, urging them to ease up on outdoor activity. "We can wirelessly manage the symptoms of thousands of patients closely," says Milani. "That's beyond the capabilities of a non-digital physician's office."

Obesity is another target. Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for example, has injected a strong digital component into its highly regarded clinical weight-loss program. Patients get a digital scale for home that transmits daily weigh-ins to an app, which makes the data accessible to doctors. It also tracks physical activity, food choices, water intake, sleep and other factors. "We use all that data to provide constant feedback to the patient," says program director Dr. Jamy Ard. "We can modify the plan, suggest different foods and activities, and set up a video visit if the patient opts for it. Because of that data, we can have a meaningful conversation."

Drug companies are developing smart drug-dosing devices that collect patient data while they're being used. Eli Lilly is piloting insulin injection pens and pumps that can gather information on how much insulin a diabetic patient injects, and when and what impact it has on blood sugar levels. Doctors download that data to monitor the patient and adjust treatments accordingly. Future versions of the devices have AI that can learn to recognize when a patient is about to sit down to a fancy meal or raid the refrigerator, and adjust dosages on the fly. Lilly is looking at applying similar data-gathering capabilities to track migraine-headache symptoms.

Calculated Risks

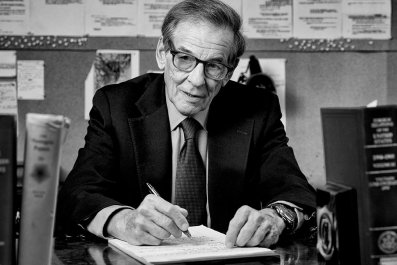

A rule of thumb in mental health is that a psychiatric patient has a slightly less than 1 percent chance of attempting suicide. That average is of no help to those patients who fall in the 1 percent, of course. If doctors could identify patients who are at a slightly greater risk of suicide, they could apportion resources to track them more closely and hopefully intervene in time. Psychiatrist Don Mordecai of Kaiser Permanente, a large nonprofit health care provider headquartered in Oakland, California, says that AI may be able to help.

Mordecai took data from 14 million patient visits to clinics run by Kaiser Permanente and two other health care systems that collaborated on the project. The data included whether or not each patient ultimately attempted suicide. Then he fed the data into "machine-learning" software, a form of AI that can identify complex patterns in reams of data that humans cannot see. The AI found 150 factors that, in various combinations, tend to signal that a patient is at an elevated risk. One factor is whether or not a patient had taken a benzodiazepine, a class of anti-anxiety drugs, within the past three months; another is whether a patient showed signs of an eating disorder within the past five years.

To see how well these factors can predict an elevated risk of suicide, Mordecai gave the AI historical data on another batch of 7 million patient visits but withheld information on which patients actually attempted suicide, leaving it to the program to make its best guess. The software accurately identified those patients who were 5 percent or more likely to make an attempt on their lives in the next 90 days. "That's much better than anything we've ever had before," says Mordecai. "It shows suicide attempts are more predictable than most medical conditions." He plans to start a pilot project later this year and eventually to extend the model beyond psychiatric patients to the general population, using data on social isolation, divorce and job loss.

Such AI-powered "predictive analytics" could be applied to many types of diseases, allowing doctors to halt or slow the progress of diseases and in some cases keep patients from getting sick. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, plans to roll out just such a pilot system later this year that is designed to flag patients at risk for multiple chronic diseases. "If we can merge enough sources of data, we can leverage AI to better know which patients are at greatest risk for which serious events, such as stroke, heart attack and cancer," says Tufia Haddad, an oncologist and researcher at the clinic.

Apostolos Davillas, a health economist at the University of Essex in Colchester, England, is putting data on the condition of communities and households, including income, education levels and culture, into predictive AI models. These "social determinants of health" are often easily obtained in government databases and can be linked to patient data. Davillas has crunched that data for thousands of patients and says that it serves as a strong predictor of disease risk.

One factor in particular has proved to have strong predictive power: the health of the spouse. "There's a sort of contagion effect of health risks in couples," he explains. "People tend to be attracted to those with similar health-related habits and genes, and then when they live together, any health risks snowball as they influence each other's habits." For example, he says, smokers tend to end up with other smokers, after which they're more likely to retain or even expand the habit over years of cohabitation. "Offering similar screening interventions to the spouses of high-risk patients would save lives," he says.

Digital approaches to medicine are creating much-needed efficiencies in drug testing. Today, clinical trials are often delayed because of the time and expense of recruiting patients. Many fail to gather enough data to produce meaningful results. About 17 percent of all trials collapse without having enrolled any patients at all, according to the NIH.

Digital medicine can pull patients in from all over the U.S., without requiring them to travel to a major medical center. The Mayo Clinic has enlisted IBM's Watson AI system to pore over the notes in breast cancer patients' electronic medical records to determine which patients are most likely to qualify for which trials. A pilot effort boosted patient enrollment by 80 percent, and now the Mayo Clinic has the system looking over the records of patients with lung or gynecologic cancers and will soon add gastrointestinal-cancer patients. "If a trial is following Parkinson's disease patients through monthly office visits, you'll end up with 12 data points at the end of a year," says Andrea Coravos, a researcher at the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science and co-founder of digital health measurement platform Elektra Labs. "If you do it at home with remote sensors, you'll get 12 data points a day."

Such studies can cost one-100th as much as conventional studies, notes Evidation's Lemke, a data analyst who used to figure out ways to target video-game ads until she decided to apply her skills to improving health. "The scale at which we can run a study at reduced cost is compelling," she says. "And the subjects are in real-world situations, not going through complicated processes at a clinical site with physicians." The company has signed up 10,000 patients for a current yearlong study of chronic pain based on data gathered from a combination of wearable trackers, environmental data, online surveys, and genetic tests and blood tests that can be taken at local labs.

Big Health Is Watching

Physicians and medical researchers worry about patient privacy—that routinely monitoring patients outside the hospital and mining their records could cross ethical boundaries. "These tools are powerful but scary, and I'm a little ambivalent," says Kaiser Permanente's Mordecai, who developed the suicide risk prediction system. "If we tell patients that our system has gone through their data and predicted they're at some risk of self-harm, some might say they're relieved and want the extra help, but some might say they don't want us looking over their shoulder like that."

He adds that because most of these systems are new and largely experimental, no one really knows how patients and the general public will react to them when they're rolled out and scaled up.

The best way forward, says Haddad, is to ensure patients call the shots on who has the data and how it's tapped. "Clinicians need to start recognizing that not all patient health data should be homed at the medical institution," she says. "The patients should have ownership, and they should be the gatekeepers. We're going to need to go to them to ask permission."

Or they can work with third parties, such as Doc.ai or Google, that can manage permissions on a patient's behalf. Third-party companies that gather, store and integrate patient data could serve as brokers that collect payment on behalf of patients from companies and institutions that want access to that data. Pharmacy and drug companies and some retailers have long compiled, bought and sold health-related data on customers and prospective customers in order to better target their marketing—health care advertising alone is more than a $100 billion a year business. Data that consumers could compile themselves via electronic monitoring would be worth much more than that, says Doc.ai's De Brouwer. Why shouldn't consumers be allowed to get in on the action? "Medical data has latent economic value that most people aren't aware of," he says. "It can be monetized."

Ultimately, government regulation will have to set boundaries on how health data can be shared, extending the protection it already gives patient health information under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The HIPAA keeps health care providers in line, but it may not apply to consumer health technology companies, which largely emerged after the legislation was enacted in 1996.

Wake Forest Baptist Health's Ard says he purposely avoided integrating consumer weight-tracking apps into his obesity program because it might violate the HIPAA or otherwise expose patients to privacy violation risks. The app, built internally, "took lots of resources to get it to where it has the privacy agreements, security and legal specifications it needed," he says. Consumer apps rarely offer that level of protection. Another issue is consumer monitoring devices' uneven accuracy, which may render some inadequate as health tools. For instance, consumer devices that monitor heart rhythm may be too quick to issue an alert when nothing serious is wrong. Too many false positives could flood ERs, causing doctors to ignore alerts.

For all the excitement over data-driven medicine and the genuine potential to improve health care, so far there isn't a large body of evidence that the approach would improve health care or lower costs in the long term. The few studies done so far turn up surprisingly mixed early results. Research published recently in the journal Health Affairs concluded that "leading digital health companies have not yet demonstrated substantial impact on disease burden or cost in the U.S. health care system." That's a major shot across the industry's bow—a warning that no matter how sensible the concepts seem, these technologies will rise or fall on rigorously proven results.

Footing the Bill

The most immediate obstacle to digital health care is the status quo. In spite of all the hand-wringing over the staggering costs and poor outcomes of the U.S. health care system, physicians, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies and health insurers are, by and large, doing just fine without digital medicine.

A case in point: Even though preliminary data from the Ochsner digital health monitoring programs run by Milani with 5,000 patients suggest that the approach produces better health outcomes and pays for itself within a year, health insurers won't cover it. Medicaid requires health providers to collect a copayment for all services they provide. That would create a burdensome blizzard of $16 copays for patients in Milani's project, which emphasizes frequent doctor-patient interactions.

One reason insurers are reluctant to pay us is that they first want to see multiple, published, large, long-term studies—not preliminary reports from projects like Ochsner's. Insurers also fear that they won't reap the payoff from up-front investments in digital health because patients in the U.S. tend to switch health plans frequently. As a result, the health care system as a whole remains needlessly costly—but in a way that keeps insurance profits high.

"It's ironic," says Ard, whose digital obesity program Medicaid refuses to cover. "Insurers aren't good about paying for these types of treatments, but they have no problem paying for the huge costs of someone going from prediabetes to Type 2 diabetes, or from slightly high blood pressure to needing three daily medications a day. Our program is getting people with diabetes down to normal blood sugar in less than a year. We need to change our perspective on what we value and pay for in medicine."

Ultimately, it may come down to waiting for doctors to push for it. Some already do, of course, but many are overworked by the enormous administrative demands of the industry's long, painful switch to electronic medical records. A jump to digital medicine might bring other burdens. "Their incentives aren't aligned with digital health," says Lemke. "They aren't being paid to monitor someone's data, and there's no way you're going to turn most of them into data scientists."

New technologies could lower that barrier and make it easier to run a digital practice, but the transition will be slow. And that's not necessarily a bad thing. Medicine, says Evidation's Lemke, "is not like Silicon Valley, where they like to move fast and break things. If you do that in health care, people die." Ultimately change will come from the people, one app at a time.